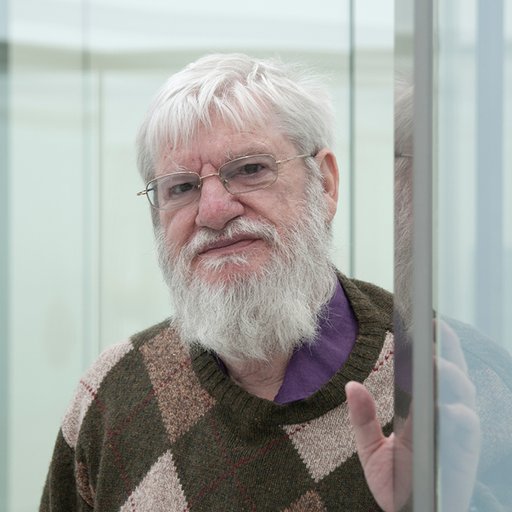

An art forger, in the popular imagination, is a romantic figure—the outsider who through preternatural skill can match artistic genius stroke for stroke, expose vaunted experts as frauds, and drive off into the night with millions of dollars liberated from affected rubes. Mark Landis, the forger whose hoodwinking of more than 50 museums across 20 states was the subject of this year’s documentary Art and Craft, does not exactly play to type. A slight 59-year-old man with Alfred E. Newman ears and an unprepossessing mien, Landis crisscrossed the country presenting counterfeit art to museums not to enrich himself—he donated the works, never asking for a dime—or lampoon the establishment. Instead, his simple con was aimed at a single target: to be viewed as a philanthropist, gaining the kind of respect that would make his late mother proud.

Landis—who grew up following his Navy lieutenant father around Europe, and who was diagnosed with schizophrenia at 17—was aided in his ruse by a remarkable ability to copy any kind of artwork through a trick he first devised as a child, and moreover to make convincing forgeries with the humblest of materials available at places like Walmart. A pop-culture obsessive who took much of the inspiration for his cons from TV and movies, he followed various scripts while presenting his forgeries to museums, including dressing up as a Jesuit priest after a character from the 1956 Grace Kelly movie The Swan. The works he left with unwitting, grateful museums ranged from Picasso sketches and Marie Laurencin self-portraits to Watteaus and Daumiers to drawings by Walt Disney and the cowboy artist Maynard Dixon.

It was when Landis encountered Oklahoma City Museum registrar Matthew Leininger in 2007 that his run began to fall apart. Presented with several works, including a Laurencin and a painting by Stanislas Lépine, Leininger discovered that several other museums had also received donations of identical works—Landis liked to copy the same pieces over and over to improve his technique—and began a campaign to bring the forger down. News stories followed, culminating in Alec Wilkinson’s 2013 New Yorker profile “The Giveaway,” which then set the stage for Art and Craft, produced by Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman.

Because Landis never profited from his forgeries, he never technically committed a crime—the onus is on the museum to verify authenticity, not the donor—so his unmasking merely turned him into a media sensation. Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the artist, who lives in his mother’s home in Laurel, Mississippi, about the motivations behind his spree, his sui-generis technique, and what he is up to now.

The new movie, Art and Craft, together with an incredible profile in the New Yorker by Alec Wilkinson has turned you into an unlikely American folk hero. What has that experience been like?

Sam and Jenn are my best friends, because, you know, we spent three years together, and I was a lonely old shut-in. When I got into trouble I was just sitting around my room, and everything looks a lot better now, okay. With the movie, I was scared to watch it at first, so I was hiding in the disabled part of the men’s room when the composer came and caught me and somehow got me to sit down. But I personally found it riveting because, as you know, everyone’s favorite subject is themselves. Once I started watching it I wanted to see what was going to happen to me, because, after all, they were here for I don’t know how many times over three years and I had even forgotten some of the people.

What is astonishing about what you have done over the years is that, as a largely self-taught practitioner, you have managed to replicate the work of great artists like Picasso and Watteau well enough to fool seasoned experts—and all with cheap materials that you could purchase at Woolworths and through processes that you largely invented. Can you talk a bit about the title of the movie, “Art and Craft,” and the difference between art and craft?

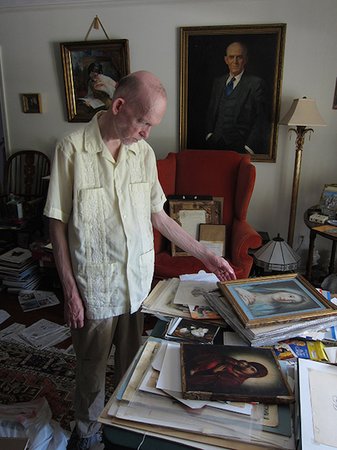

I’m probably not qualified to do this, but I know that when I was at the Menninger Foundation [psychiatric clinic] I would go to their center for arts and crafts, which was one of their daytime therapies or what have you, and I knew I had a facility for arts and crafts—I used to be a lot better at drawing when I was younger than I am now. But as far as the art part goes, I’m fairly good at copying things, and as far as craft goes, I’m good at buying cheap frames at discount stores and making them look like they’re antiques, or buying cheap plaster garden statues and working on them with sandpaper and maybe weighting them with some rocks or whatever I can find at the base to make it look like a nice marble statue. Now that’s craft to me. Craft to somebody else might be basket-weaving and stuff like that.

You’ve also made art under your own name that you’ve displayed in a few gallery shows.

Most of my success—and very limited, modest success indeed, let’s be clear about that—is because a lady in Laurel, Mrs. Elizabeth Rogers Wyndham, whose family founded the museum here, took an interest in me and found all these ladies in the area to have me paint their grandchildren and children and pets and their houses too. One lady had just come back from a vacation in Italy and she brought all of these snapshots from her trip, so I’ve been painting those and that’s what’s keeping me busy. And of course I sign all of those things with my own name.

Between the art you make as Mark Landis and the art you make as Daumier or Signac, do you prefer one or the other?

Well, no. I’m sort of the same as anyone else—I have good days and I have bad days, so some days I’m better than others. And for someone my age it’s important to keep busy. I’m sure you’ve seen enough situation comedies or even known enough people to know that old guys go down when they retire, because they haven’t got a thing to do but sit around. In fact, I think I saw something when I turned on the computer a few days ago that said that old guys who have retired are dead in five or 10 years—they just go down. So I’m being kept busy now, and Sam and Jenn have certainly kept me busy.

One of the most enthralling parts of the movie is when you’re demonstrating your “memory trick,” placing a blank piece of paper over a picture of an artwork and flipping rapidly back and forth between the two as you draw, allowing you to create a tremendously convincing copy. How did you discover that ability?

I don’t know, it’s been so long… I was a child, that’s for sure. I grew up in Europe, and we didn’t have TV sets in the hotel rooms, so there wasn’t anything to do. But during the day dad and I used to go to museums because mother liked to shop anyway, so there would always be museum catalogues lying around. And I do remember being about 10 when I started doing it. I used to like to do Madonna and Christ childs for mother—mother didn’t like martyrdoms and she didn’t like battles, she liked Madonna and childs, and everyone wants to please their mother, so…. I guess I found it hard to actually copy, but I found I could do it that way.

What is it that you liked so much about art as a child? Was it the stories that gripped you, or the way they were made?

Well, I used to do battles for dad. I’ve still got a Trafalgar I did. Dad liked to read history books, so I definitely liked religious and historical paintings, and also realistic things. A lot of times people ask me what kind of artists I like, and I always say, “Victorian stuff, the sappier the better.” I like cute children and cute kittens, stuff mother would have liked, and angels, girls playing the lute. Nothing’s better than that.

Over the years you’ve also developed a repertoire of techniques that allow you to approximate the physical appearance of vintage pieces of art—for instance, one scene shows you using coffee to give a frame an artificially aged appearance.

Well, it gives it a superficial impression—after all, most people don’t look at things, and they don’t let you get that close in a museum anyway. But then the X-ray people come in, and they’re always taking things down and changing them around, you know.

What are some of your favorite techniques or tricks that allow you to approximate the appearance of older art, and that when, combined with your copying, can make a forgery look incredibly convincing?

It kind of depends on the picture, and things just sort of occur to me when I’m doing it. One giveaway is to overdo it—you don’t want it to look ridiculously old. You wouldn’t want to put too much coffee on something when it’s only 100 years old. Also, you’d be surprised—there are pictures that surprisingly look just as good today as when they were made. I mean, there’s some paper from nearly 200 years ago that looks like paper that’s only a few years old.

You’ve said before that having a convincing signature is often enough to get people to immediately accept a work as really and not probe any deeper.

Yeah, the signature is important. Having a good label and some stamps on the back always helps.

What’s interesting is that you managed to make convincing forgeries without using any kind of archival, 200-year-old paper, which someone else might have gone out and sourced. Instead, you would simply work with the cheap modern paper you had at hand.

I have seen movies and TV shows and even read a little bit about some of the famous people, because everybody knows about [Vermeer forger] Han van Meegeren and [Modern-art forger] Elmyr de Hory. But, you see, they were selling the things and they had to worry about…. Did you see that movie How to Steal a Million with Peter O’Toole and Audrey Hepburn? Her father was a professional forger and he was afraid of some kind of scientific test. I haven’t got that kind of patience. If there’s any such thing as attention-deficit disorder I’ve got it. I was always happy with just making a good superficial impression and then, fortunately, when a museum found out, I was long gone. So I didn’t have to face anything.

When it came to presenting your forgeries to museums, it seems you had a fairly good understanding of the blurry line was between what was legal and what was illegal. Where did that awareness come from?

I didn’t have any awareness about legal stuff at all, aside from what I saw on “Perry Mason” or something. What happened was that 30 years ago I had an impulse to give away a picture to a museum because I wanted to impress my mother, and I had noticed that they always had labels next to paintings saying, “Gift of so-and-so,” somebody rich and important. I had seen people on TV donating pictures—in fact I even saw a “Perry Mason” episode where there was a lady donating a painting to a museum, and I guess that just made an impression on me.

And what happened when I gave away the picture was that everybody treated me so much deference and respect and even friendship—these were things I was quite unfamiliar with. Really unfamiliar with. And I liked it and got addicted to it. It could happen to anybody. I got addicted to being treated like that, like a VIP, and I think everybody could understand that, too. Because I had very poor self-esteem for obvious reasons when I was younger, and I still do. Nobody ever treated me like a person of importance or worthy of any respect or deference. So I got addicted to it, and kept doing it.

Is it just pure luck that you managed to create these forgeries and give them to museums but just be exactly one step outside the definition of a crime? Because there were people pursuing you for years who believe you broke the law.

What happened was that it just worked out—that’s a pretty good way to put it. You see on TV that people doing all kinds of awful things, and that’s because they’re not thinking that they’re addicted to something. Anyway, I got addicted to philanthropy, and I never thought about these things until until after I was long gone, and that was basically when I was alone pacing around my room. The only time I remember getting nervous was when I had plans for a museum drawn up in dad’s memory. But that’s because you just get carried away, you get extravagant, which I guess everybody does from time to time. But in terms of thinking about it, I guess I just didn’t think about it. I guess I was lucky in that way.

Is it true that you never made money off the sale of these artworks?

Well, I’ve made some money from selling my own things, but not with the museums. But that’s pretty hard to do—that’s where you do have to be careful, because that’s something they would look at pretty closely, I would think.

So how did Alec Wilkinson from the New Yorker manage to find you?

Oh, Alec? He, uh, sent an overnight Fedex with a real nice cover letter, and of course he seemed like someone I’d really like to talk to. Because after all, who wouldn’t want a glamorous, sophisticated New Yorker writer to take an interest in you. I hadn’t been answering his phone calls because I didn’t know who he was and I was getting calls from all over the place—the New York Times, “60 Minutes,” the Financial Times.

And you didn’t talk to any of them?

Well, no, I thought it was something like ratings sweeps or something like that, and with the Financial Times I thought it was because my mother used to get Fortune as a complimentary subscription from one of the mutual funds she had—I thought it was just a subscription thing.

But other people were trying to find you too.

Well, also, my voicemail always gets filled up, so I didn’t listen to anything. I saw a couple calls coming in, but I just took it for granted that they were subscription bribes or rating sweeps or things like that. But then what happened was that John [Gapper of the Financial Times] came down here and was banging on the door all day and late into the night, but I didn’t open it because I didn’t know who it was. I thought it was someone who might be mad at me.

But every weekend I used to check the Laurel homepage to make sure I was still a notable resident, and that weekend when I checked it I saw something negative, and that led me to an article in a U.K. paper called the Guardian, and that was when I first realized that I was in trouble. I read a little bit about it and it said something about me being treated like royalty—and that was kind of close, but it took it a little too far—and anyway I kind of put two and two together, to use an old saw, and thought, hmm, the Financial Times is a U.K. paper—maybe somebody over there wants to talk to me.

So I called him back, and he was back in New York, and we hit it off because we had a lot in common—we both went to public school, we got our long pants in upper form, because I went to school in London when I was 11 and 12. So he came down here again, and I guess in a way that was luck, because I could have talked to somebody else and they might not have been as sympathetic a journalist.

And when did you first find out about Matthew Leininger—that you had a personal Javert on your trail?

Four years ago, or something like that. It’s not as if I had never had people mad at me before. I just don’t answer the phone and close the mailbox and that sort of thing.

What do you make of his campaign to have you arrested?

Oh, no. I’m more or less used to people being mad at me. It scared me some a way back, but now it doesn’t. And I wouldn’t have recognized him if I had seen him. I remember when I was at his museum I only talked to him for about five minutes, but I usually don’t spend too much time with people. I’m not even sure what a registrar does. I think it has something to do with cataloguing things. Do you know what a registrar does?

Now he plays a very prominent part in your movie, which portrays him as your nemesis. How do you feel about him having such an central role in your story?

I don’t know that he has a big part. But anyway, he deserves it, he deserves it. I’m sorry I caused so much trouble. I had never even heard of OCD before, but apparently he’s supposed to have it. I heard that term a few weeks ago. You know, I’m not reflective by nature. Like I said, if there’s anything such as attention-deficit disorder or whatever, I’ve got it. I don’t sit around reflecting much. You know something? If I sat around worrying about everybody that might or might not be mad at me, or all of the bad things that might happen to me, I really would go off the deep end. I believe that worrying about tomorrow is a waste of today.

You said you were drawn to forging artworks because it was a way of gaining respect from museums that viewed you as a philanthropist. Did it ever occur to you to try and gain that respect by putting your skills toward being a celebrated artist in your own right?

That’s extremely flattering, but I don’t believe that I could. I’ve always liked to draw and paint and to do arts and craft, as long it’s not too big and messy and I can get it done real quick—before a movie is over, ideally. When I came back to the United States I went to USM and studied economics, but as I said I can’t stick with anything, so I dropped out of college. Then there wasn’t anything to do, so I thought I would take up art and I had little if any success in finding galleries to represent me—or when I did they would drop me fairly quickly, probably because I did the same things over and over again. Also, I would get careless and that sort of thing.

What do you make of the world of galleries and contemporary art?

Well, you know, I’m not really qualified. I just don’t know much anything about it. I’m certainly not mad at it. I’ve seen that “Perry Mason” episode and other TV shows where there's a frustrated artist. Have you seen that “Perry Mason” episode in season two with the art forger who actually did it? It was a good episode. They kept calling him a “hack.” Well, I am a hack! [Laughs]

Here in Manhattan, in this world capital of contemporary art, there are artists who are making millions of dollars off what’s known as appropriation, where they copy other artists’ work and present it as their own, doing it as a new, rebellious way of making art. Have you heard about that?

I didn’t know about that! I wish somebody would let me in on it, because I might be eccentric but I’m not crazy. Sure, I’d be happy to copy some art as a rebellion against whatever it is somebody tells me I’m supposed to be rebelling about and make a million dollars. Tell you what, you find out how to go about it and we can split the million dollars, okay?

That sounds very fair to me. [Laughs] You should look up the artist Richard Prince on Wikipedia. So, do you still make any copies or are you only making original pieces now?

I did a Winslow Homer for the Canton Museum of Art and they sold it for $800 for a benefit. That doesn’t sound too impressive compared to the other stuff you’ve been talking about, but it impressed me. I like that sort of thing. And this was a cute little girl picking geraniums. That’s the kind of things mother would have liked too.

Now museums are coming around to you on your own merits, and the Los Angeles Times has even called you a “real-deal artist” in your own right. What do you make of these developments?

You know something? Even though I’m not given to reflection I’m going to have to reflect on that, because it’s news to me. I just heard it from you. It’s hard to answer a question like that, because it just hits you right here.

What are you working on now?

Well, I’ll tell you I just finished a big bowl of geraniums for a friend of Mrs. Wyndham, Mrs. Gardener. Her family is one of the founders of Laurel. And you know who else I did a portrait of? Our most famous resident is Leontyne Price, and her brother is General Price, and his wife, Laura, is an opera singer herself and she had me do a portrait of her. And all that came to me through the goodness of Mrs. Elizabeth Wyndham, who took an interest in me.