Margaret Lee is a triple threat. She's an artist, known for creating photographs, sculptures, and installations that take humdrum subjects (produce, polka dots, etc.) and charge them with strangely urgent meaning—a body of work that won her the 2012 Artadia Award. She's a gallerist, the founder of the Lower East Side's 47 Canal, an operation dedicated to showing artists whose Internet-bred work pushes forward the vanguard of contemporary art. And, somehow, she's also the studio manager and right-hand abettor of one of the most famous artists working today (Cindy Sherman).

How does she do it? And what is she doing, exactly? To find out, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with Lee in her studio—located a few floors above her gallery on Canal Street—to talk about her destabilizing art.

Related Links:

Q&A: Margaret Lee on the Unlikely Rise of 47 Canal, Her Artist-Run Gallery

How did you first get drawn into the idea of being an artist?

I always liked art when I was a kid, and I was always really good at replicating things, like painting flowers or really banal things like that. And my parents would always take me to museums, not so I would be an artist but so that I would be a cultured person. I grew up in Yonkers, and my parents had a bodega in the Bronx, which was cool because my sister and I could catch a ride to the Bronx with them and then take the 4 or D train into the city and explore. But while they really encouraged us to be cultural—I played the piano, for instance—they never wanted me to be an artist, so I went to a regular college.

They didn't want you to be a visual artist?

Any kind of artist. [Laughs] Not a dancer, not a musician, nothing. So I studied history at Barnard, and in the second semester of my junior year I decided I wanted to take a sculpture class, because I was always good at ceramics and working with my hands. All of the arts classes were at Columbia, and at that time, around 2000, Columbia’s MFA program was just starting to become a big deal. So I walked in and I saw that the instructors were super cool-looking, not old fogies—and the professor was Keith Edmier and the teacher's assistant was Banks Violette, who was doing his second-year MFA.

I had never had access to actual contemporary artists before, and we just went into it. My first assignment was to make something really personal out of foam, and I'd never been asked to be introspective in that way—I didn’t think I had wanted to tap into those feelings—but somehow it was the first time in my life that I felt I could create a balance between my outside personality and inside personality. So I really enjoyed making that sculpture, and I was really good at the making part.

A view of Margaret Lee's studio

A view of Margaret Lee's studio

What was it?

It was the façade of the Alamo. I was a U.S. history major, and I had been thinking about the Alamo a lot at the time and the idealism associated with Manifest Destiny and how that related to capitalism—in other words, the rhetoric of American democracy and how fucked up it was. So I played with that, and then I realized I was actually good at speaking about my work and other peoples work. I knew I wasn’t as good at history as other people in my major, and it was the first time I found I had a real voice doing anything. So from that first project I realized that this was what I wanted to do.

Then people like Keith and Banks showed me work by artists I had never heard of. I really only knew Matisse, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and artists like that, so seeing things by people like Robert Gober for the first time was really amazing. But I couldn’t change majors, so I finished my history degree.

Who were some of the other MFA students who were teaching undergrad art classes at the time

It was kind of amazing. David Altmejd was there, Barnaby Furnas was there, Dana Schutz came in the next year. Just going to those MFA shows early on was amazing—the first Columbia MFA show I went to was in a warehouse in Williamsburg in a third-floor walk-up across the street from Kokie's. The program was different back then—it wasn’t this big fancy program. So I just continued to take sculpture classes there, and after I graduated Keith hired me to be his assistant.

A sculpture in progress

A sculpture in progress

I think one really interesting thing about your trajectory is that you never actually went to art school, yet you somehow managed to penetrate the inner sanctum of the art world and build a very exciting career by taking the apprenticeship track, in a more old-fashioned vocational way. What do you think you gained and what do you think you lost by not getting an MFA?

I don’t really have a studio practice, and I think people who go to art school have a studio practice.

What do you mean?

I only make works on assignment, or if I have an idea then I'll make it, because I’ve never been trained to just continuously keep working. I remember listening to kids who went to art school, and their assignments were to make a drawing every day in order to keep their creativity loose, or to get to new places they didn’t know existed—you just have to sketch and sketch and see where it takes you. I never sketch, I just sort of have an idea and it’s so clear in my mind that I just go towards it and figure out how to make it. So I don’t have a studio practice, and I don’t really like making art. I mean, I like to make art, but I’m not someone who could be in my studio all day by myself. I find it kind of depressing—too isolating, in a way.

The sculpture being installed at Jack Hanley Gallery

The sculpture being installed at Jack Hanley Gallery

So you just wait for inspiration to strike and then make it become a reality, rather than constantly experimenting and seeing where things take you.

Yeah, and the making part is really just about getting it done. Sometimes it's enjoyable and I forget about everything else in my life, and then eight hours pass by. But a lot of my work isn't gestural, so it's less like pouring my soul into a painting than it is like just finishing something—like, I know how to do a watermelon, so I make a watermelon. I’m trying to sketch now, but it doesn’t come naturally to me.

Your sketches look great.

Thank you! They look like art with a capital 'A,' whereas usually my art doesn’t look like art. But with my watermelon sculptures, if someone had given me a sphere and told me to make it look like a watermelon, I could have made them in my first art class. I was born with this talent, so it just comes to me—I could have been a set designer in a previous life, the person making the dioramas in the Museum of Natural History. I like having an idea and seeing it through, versus having a feeling and needing to make it into an idea. It’s pure feeling.

It's funny that you say you don’t have a studio practice, because it seems to me that your studio practice is just living in this world of commercial, theatrical, and digital imagery that you're surrounded by and mining it for ideas to turn into art.

The commercial part is the biggest influence, because I grew up in an immigrant family and I never felt entitled to the world I was growing up in—I felt like I was outside of it. My parents barely spoke English, and they didn’t know how the Western world worked. On the other hand, I was a total media sponge—I would just look at everything Western and think, "This is how the world should look." My house always looked weird because it was this big mishmash of East and West that didn’t make sense, and then I’d go to someone else’s house and all the plates matched and all the things were in order.

You can see this in my work, where I'm idealizing that sort of sterile control. But the flip side is that after years of processing it, I started thinking about myself in relation to that, so that when a collector with a pristine home buys a piece of mine I feel like it’s this interference of taste. I kind of sneak this other thing into their homes under the guise of art.

An artwork that was included in the recent White Columns benefit auction

An artwork that was included in the recent White Columns benefit auction

Does your frequent use of produce in your art come from the fact that your parents had a bodega?

Probably. But also, Western food always looks so perfect. Everything would look perfect when we would go food shopping at the supermarket, but then in the Asian market it was, "Uh, that’s a squid," and everything smells weird, and while there were apples and pears and things like that, it wasn’t all perfect. And there were exotic things that people didn't understand. When we grew up, the lettuce I wanted to eat was iceberg and the apples I wanted to eat were red delicious. It wasn’t artisanal—it was all genetically modified, you know. I could have eaten the most amazing food, but instead I just wanted Wonder Bread and Red Delicious apples and bananas instead of old country food.

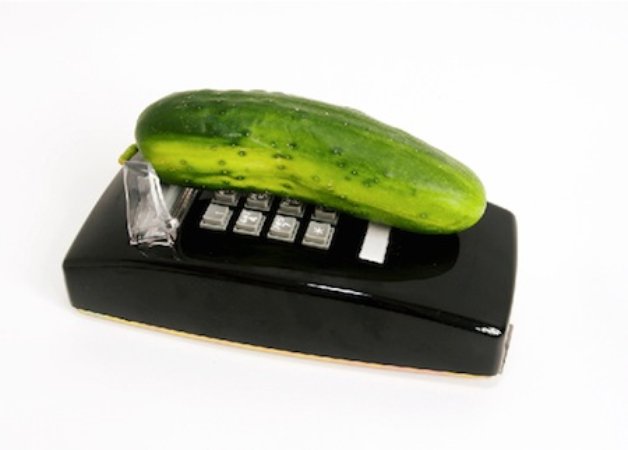

There's a strain of surrealism running through your work that seems to arise from this collision of banal, everyday staples with the strange potentialities of technology. Your cucumber phone, for instance, at once is reminiscent of classical Surrealism but also feels incredibly fresh and relevant. Why do you think that is?

That cucumber phone is one of my favorites. I wasn't thinking about the lobster phone—it didn’t start from that, because the lobster itself is so exotic and I don’t work with anything exotic, so I could never go there. I think it came from a time when I was working so much I was delirious, and I could just imagine holding a cucumber to my ear and saying, "Yes, yes of course I can do that," and doing all of my business. But I was also thinking about how things change so quickly. Children don't know what telephones look like when they are not rectangular, especially that kind of phone, which was a big part of my childhood, on the kitchen wall. And I was also thinking about how food is marketed, how it used to be one thing but now is something else.

So, that type of cucumber is sort of passé—it's like, "That’s not from the farmers' market!" Everything can be marketed to change one's desire, and all of my work comes from investigating the concept of desire—my own desire, which I sublimate into the work, and then creating things that are desirable to other people, and getting a kick out of the fact that they're desiring that thing. Basically, none of it makes any sense. I spent my whole life trying to fit in and be a normal Western person, and now we're all going back to the food that I grew up with, where everything is weird-looking, natural, and organic, like it was plucked from a garden. It's like, goddamn it, I finally got to this place and everyone's going somewhere else.

Who makes these decisions? There's a larger machine that we're all affected by. So my work is about desire and trying to find yourself, and how capitalism teaches you that you have to find yourself through consumption, and that you define yourself by what you consume.

Cucumber Phone (2012)

Cucumber Phone (2012)

You often make gridded compositions, where everything is placed within a high-tech matrix that's familiar to contemporary audiences. With your cucumber phone, then, the viewer realizes that the genetically modified cucumber is just as technological as the phone receiver. Do you see these scientific advances as positive?

I don’t think I would say these advances are positive or negative, but rather simply that they're dramatic. I believe we are going through something similar to the last industrial revolution. The beginning of the 20th century brought great technological advances but also created the machines that introduced the world to horrors never seen before. The mass destruction brought on by WWI shocked the world, and artists definitely reacted strongly to it.

Now we're going through a new technological revolution brought on by the internet. Everyone experiences things online, and when it comes to artworks, questions like, "Is it a sculpture? Is it an image? Is it an installation photo? Is it digitally manipulated? What is its texture?" All of these are less important. Real, fake, who cares—right now it's just about getting information out there. I feel that there are more platforms than there is content, and I always joke that that's why there are so many cats on the Internet—you just have to fill the space!

It's funny, because a lot of the artists in my gallery also deal with this drastic shift that we're going through right now in a very different way—they're actually using these new technologies. People say, "Your artists are always using 3-D printing, or it's all Plexi, or it’s a hologram, but you’re so old fashioned," and I say, "Yeah, but it’s the same conversation."

An installation view of a show in Lyon

An installation view of a show in Lyon

What do you mean when you say now is a time when you can get away with things in your work?

It’s a time when I don’t think people can feel comfortable, because things are changing so quickly that we're all sort of accepting that we're in limbo. But it’s an exciting time to be an artist, because we're all stuck in a suspension of disbelief. I think eventually the Internet will be very regulated and everything will be tagged correctly and you probably won't be able to get away with things you can now.

So, how did you start working for Cindy Sherman? It must be a fascinating experience.

When I graduated from college I worked for Keith Edmeir and Bonnie Collura for about six to eight months—I had studied with both of them at school. But then Keith moved away and Bonnie moved her studio, and I got passed on to Michelle Segre. Michelle was best friends with this woman named Susan Jennings, who's an artist and is married to the artist Alexander Ross. Susan had been Cindy Sherman’s assistant for six years and was looking for a replacement. She was also going to sublet Keith’s studio and apartment when he went to L.A. Also, Susan’s younger sister was randomly my older sister’s first roommate in college.

So when she was doing background checks on me it was sort of this weird thing, where she was like, "Oh, and you even known my sister, and I also know your sister, even though neither of us knew the other existed." So everything kind of fell into place, and everyone recommended me, so it worked out—because it's a really hard job to give to someone, and it's hard to find a stranger who's really trustworthy.

The view from Lee's studio window

The view from Lee's studio window

How would you say the experience has impacted the way you make your own work?

I guess there's a meticulousness of Cindy's pictures that I've found very inspiring. Everyone thinks she just takes pictures of herself and it's about the act of transformation, but because I look at them so much I know how detail-oriented they are—there's not one hair out of place. But her being a part of the Pictures Generation is meaningful, because that's probably what influenced me the most, being exposed to Metro Pictures and artists like Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo. I learned that history so well. I was always really drawn to the legacy of appropriation, so it was really inspiring to see first-hand.