Modernist ballerinas wield AK-47s, low-flying bats loom over hooded figures, and mutilated cowboys abound against horizonless and shadowless backdrops. Needless to say, we are in the entirely distinctive world of Marcel Dzama, whose finely hand-drawn illustrations—equal parts Surrealist affront to rationality, children's-book cartoonishness, and the upbeat malevolence of Edward Gorey—have earned him a popular profile rare for a fine artist who, at the end of the day, specializes in works on paper.

These days, however, Dzama is energetically entering into new medims and even the worlds of other artists, as in his new short film Une Danse des Bouffons (“a jester’s dance”) that is currently showing at David Zwirnerin New York. The silent movie opens with a two-faced trickster awakening the prone nude of Étant Donnés, the peep-holed masterpiece that Marcel Duchampmodeled on his lover, the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins (played in the film by both Sonic Youth’sKim Gordon and the model Hannelore Knuts). From the start, it's clear that this is a work of abundant cross-pollination.

A surreal saga unfolds: Martins must save her artist lover, held hostage and forced to numbingly recite chess moves: "Knight G1 to G2." (Here, Duchamp is literally a “victim of chess,” as he famously claimed.) Later, Martins watches FrancisPicabia’s Adoration of the Calf dance to the Spanish guitar while she balances a chair on her head—evoking a picture from Goya’s “Los Caprichos” etchings—and witnesses Joseph Beuys’ felt blanket transform into a talisman. Somehow, it all fits together into what Dzama calls a “Dadaist love story” and is scored by the Arcade Fire's Will Butler, Jeremy Gara, and Tim Kingsbury.

In an attempt to understand this new body of work, and how it fits into Dzama's larger career, we spoke to the artist about childhood terrors, the black wig worn by Kim Gordon, and tricksters in mythology and art history.

A still from Une Danse des Bouffons

A still from Une Danse des Bouffons

There are many sets of doubles in Une Danse des Bouffons. To begin, two versions of the film—one in a red room, one blue in a blue—play in adjacent theatres; lovers lying prone replace the single figure in Duchamp’s Étant Donnés; even the jesters’ masks are double-sided or are furbished with extra pairs of eyes. In art history, doubling is a signature move of Surrealists and Dadaists, who believed in a double reality, one driven by desire and attraction, the other by disgust. Can you talk a bit about how the film and its absurdist sensibility came together for you?

The original idea for the film came after the Toronto Film Festival announced it was commissioning homages to David Cronenberg. A Cronenberg film, Rabid, is actually one of my earliest memories. My parents had taken me to a drive-in theater for a triple feature, and it was the last film, so I was supposed to be asleep—but I wasn’t, and could see the reflection of the film in the back of the station wagon. It would kind of haunt me later, because I was way too young to see it then. In the film, this woman gets in a car accident, and, for some reason, to save her, a plastic surgeon gives her this weird stinger that’s in her armpit and she becomes a kind of vampire who makes love to people and stings them and turns them into zombie creatures who then are rabid and foam at the mouth. [Laughs]

So, I really like his work, but in my film I also wanted to pay homage to other artists who influence me as an artist: Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Joseph Beuys. I wanted to bring their works to life, so Étant Donnés at the very beginning comes alive. I wanted that female figure in Duchamp’s work to become a heroine of the film. And the doubling idea fit well with the theme of chess, Duchamp’s obsession outside of art. I wanted to represent two sides of the board, with a varied color scheme—I couldn’t have just a white side or a black side for the exhibition.

So, instead of zombies, you set out to bring older works of art back to life. The film centers on Duchamp and his last artwork, ÉtantDonnés, createdafter Martins returned to her husband. What captured your imagination about their ill-starred affair and Étant Donnés?

That piece was so disliked when it came out—and misunderstood. It was seen as this terrible rape victim when really it was almost a love letter to Maria Martins. I kind of wanted to play more with that idea, to revisit the original feelings.

Did that involve a lot of research on your part? You once said that when you were a a kid one of the first books you checked out from the library was the biography for Marcel Duchamp.

Yeah, because of our shared first name. [Laughs] There’s this great book by Michael Taylor, who used to be at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, that’s all about Étant Donnés. It has every detail you could possibly imagine, like how Duchamp rigged the waterfall in the background and staged everything. Taylor also reprinted a little book about how to repair and set up the work, like an instructional manual for the museum, which I also have.

You weren’t exactly faithful to the original when you reconstructed it for the film.

Yeah, I shifted everything a little to the left, because the original cuts off her face and part of her arm. Mine continues to show her face, her arm, and next to her, the body of Duchamp that appears at the end.

An installation shot of “Une Danse des Bouffons” at David Zwirner

An installation shot of “Une Danse des Bouffons” at David Zwirner

How did the plot evolve for you?

Well, I had these images that I wanted to bring to life, so the plot worked around the images. And I had a lot of drawings that I’d done earlier that were almost like little storyboards for a film. Then I wrote the story afterwards—there was a loose story when I was doing the storyboard, but it changed quite a bit. Originally, it was about two sisters. But it didn’t really make sense, and I wanted it to be more about Duchamp.

The images you bring to life include artworks by Picabia, Goya, and Beuys, plus Oscar Schlemmer’s costumes, Busby Berkeley’s films, and a Nigerian mythological figure. Do you encourage audiences to hunt symbols and trace references in your work?

I like putting little things in there for people who will appreciate those historical facts, but I want it to be entertaining for someone who doesn’t have that knowledge as well. I want it to still make sense, but you wouldn’t necessarily need to know the entire background.

The characters populating your menacing, whimsical worlds are distinct and recurring. In this new show at Zwirner, we meet two new characters in your repertoire: the four-eyed man and the dancing jester.

I was really influenced by this book by Lewis Hyde, Trickster Makes This World. I was looking at all of these tricksters and incorporated that into the film, so I wanted trickster figures throughout the drawings as well: Greek, African, Native American mythology. The author even mentions Duchamp and the Dadaists as tricksters in the art world.

What appeals to you about that playful, devious figure in mythology or in art?

I love when art or mythology has a sense of humor—I feel an immediate engagement that transcends time. Personally, I have always used humor to lighten something more serious. If I want to speak about something serious, humor can diffuse it or add layers.

As an artist, do you think of yourself in this waggish role of trickster, too? If so, what are your "tricks"?

In the drawings and films and even the sculptures, I do find myself in a bit of a trickster role. I love putting different characters into absurd situations that you wouldn’t typically see.

Another still from the film

Another still from the film

Kim Gordon is put in some absurd situations in the film. She commands a strong theatrical presence on camera, donning a cute black bob and acting in an antic, girlish manner. Why did you choose her to play Duchamp’s lover?

I wanted to have a strong female character who wouldn’t seem like a victim. I wanted her to be in control of the situation—even though it was out of control—or as if she almost didn’t care. And actually, I went to a wig party with Kim before Christmas. I brought a whole bag, and Kim didn’t have one, so I gave her one that was very similar to that one, and it looked so great on her. But I was still very shy about asking her to do the film. I just thought, who am I to ask Kim Gordon to star in my film? But I got reassurance from my friends and my wife. I was very lucky. She did some great improv and gave it so much more character than I had written in storyboards.

What is your approach to directing?

I kind of want the actors to feel free to try things. Since it wasn’t a talkie, it was much easier—I would even just say what they’re feeling out loud during the filming: “upset” or “surprise.”

You have a history of creating communities around art making, from the Royal Art Lodge at university to collaborating with artists like Beck and Dave Eggers. In this film, you’re working with Vanessa Walters, who dances in the film and feature music by Will Butler, Jeremy Gara, and Tim Kingsbury. What do you get from these artistic collaborations that you don’t sitting at your desk alone?

It can be very lonely just drawing all by yourself. And, I mean, it used to be me drawing alone in a basement, which is extra-depressing. Having a friend next to you, you can have a conversation and you can learn so much from each other. It’s also nice to be able to get someone else’s opinion when you're kind of lost.

Installation shot of Une Danse des Bouffons at David Zwirner

Installation shot of Une Danse des Bouffons at David Zwirner

How did the musical collaboration for the score of this film come about with Will Butler, Jeremy Gara, and Tim Kingsbury?

I’d asked Jeremy if he’d be interested to make music for a film, thinking I’d make the film based on music. I thought that would be interesting way to write a film, I guess it would have been like a music video in a way. He agreed to do that and Will was interested and so was Tim, so I had that part ready to go. But I’d shot pretty much all the film at that point, so it was done the proper way, not the reverse way. They just worked with minor bits of information, like, “This is a suspenseful scene. This has a kind of Black Orpheus guitar feel.”

You’ve said before that you were staging a “rebellion” of sorts against the technological direction of art today though your intricate, hand-drawn work. In your film, there’s also a quaint quality: it’s a black-and-white silent film.

I’m not sure why, but sometimes it seems that you lose the intimacy of the image if there’s too much intervention. I guess with this film, though, it’s a little different, since I did shoot it with a digital camera. I didn’t want to originally, but it made sense for the budget. I still did my best to make it feel like film. So, yeah, I still think there is part of me that’s rebelling against technology. It took me forever to get an iPhone. My gallery actually bought me one because they couldn’t get ahold of me.

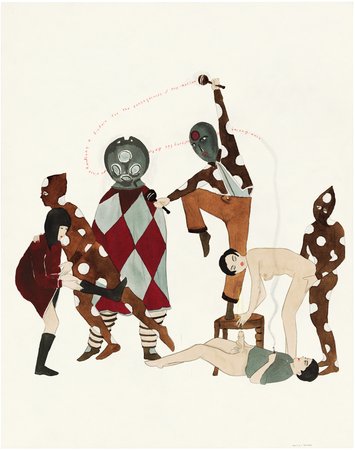

A Disdain for the Consequences of Any Action (2011)

A Disdain for the Consequences of Any Action (2011)

Likewise, you use a subdued color pallet—browns, vermilions, and olives—like samples from antique children’s books. At Zwirner, though, there is a blue room and a red room of your drawings. Were these objects made in conjunction with the film, or after? How do the drawings fit together with the film, and how do you feel your work in one medium fits with your work in another?

I started with the storyboards, and then made the film, and later on the drawings. They’re like prequels and sequels to the movie—their own little stories. So while a few of them pay reference to the film, most are different versions of it. But when I draw, I’m usually listening to music. But when I’m painting I listen to classroom DVDs or books on tape because I feel like I can double-task—especially with this show because it was all one color.

What are you working on next?

Right now, I’m working on a show in Düsseldorf and on some things similar to those long dioramas in the show. They were the most recent work. I’m slowly trying to put together some ideas for a feature film, too, which I might try to do next winter. The story for that is… well, it’s kind of a coming-of-age-story about this gang of girls, but all taking place in my weird world.