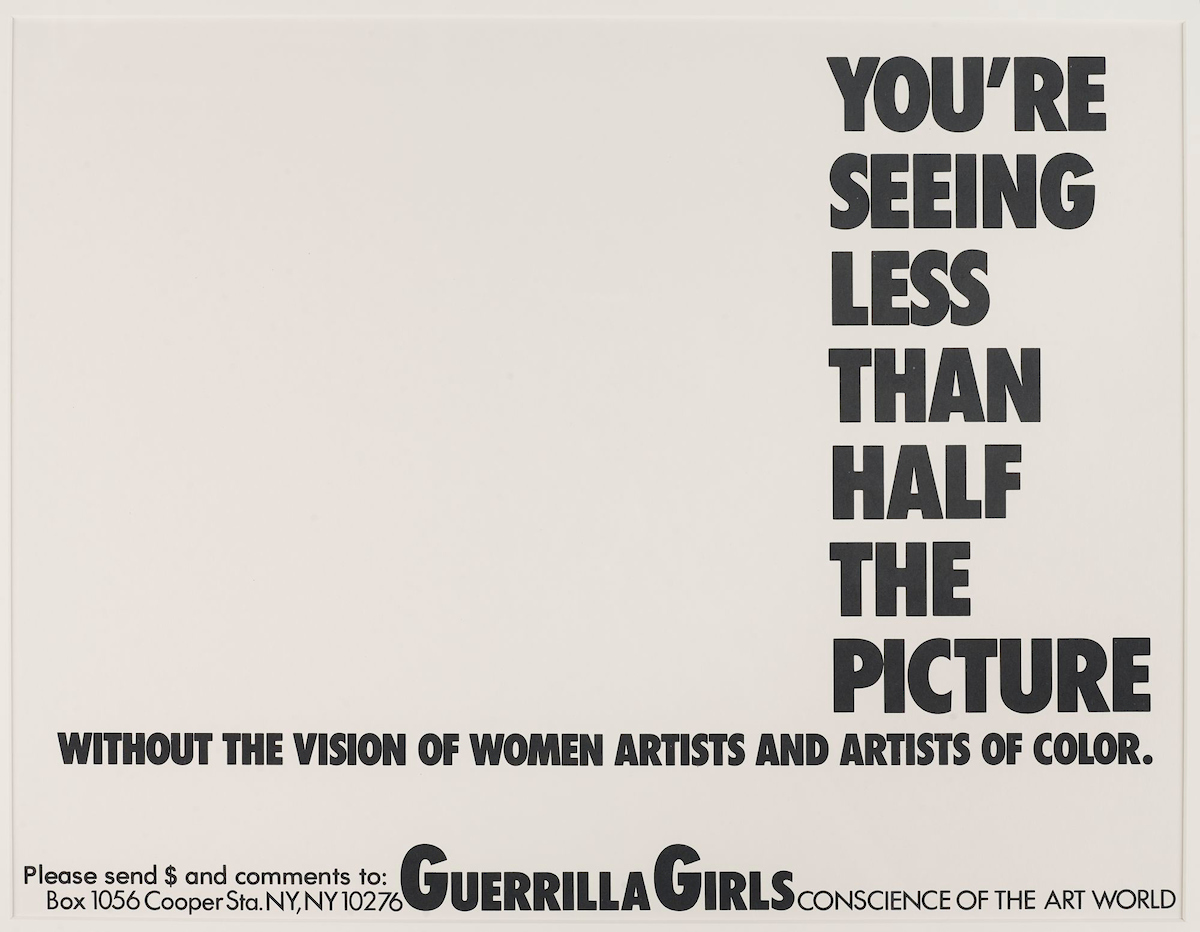

In 1989, a collective of anonymous feminist artists operating under the alias “Guerilla Girls” released one of their many iconically wry and astute posters addressing gender-based inequity in the art world. It highlighted the lack of institutional representation in the arts and pointedly declared, “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color.” Taking heed of this historic work of protest art, the Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibition “Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection” reviews the institution’s holdings through an intersectional feminist lens, sifting through one hundred years of art history to bring us a little bit closer to a complete version of the picture.

Curated by Catherine Morris, the senior curator at the Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum and Associate Curator Carmen Hermo, the exhibition brings forth over 50 artists whose works advocate for their communities, their beliefs, and their hopes for equality across race, class, and gender. On view through March 31st, 2019, "Half the Picture" creates an exciting model by which institutions may continue to critique themselves. In the following interview, Morris and Artspace's Shannon Lee discuss this trend in curation, the intricacies of going through one hundred years of the Brooklyn Museums collection as a feminist, its implications for the institution, and why now more than ever, we need to be approaching history with an attitude of inclusivity.

You're Seeing Less than Half the Picture 1989 by Guerilla Girls. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

You're Seeing Less than Half the Picture 1989 by Guerilla Girls. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

How long has this exhibition been in the works?

Last year was the 10th anniversary of the Sackler Center and we had an entire year-long curatorial project called "The Year of Yes," which was meant to tease out examples and think about methodologies of feminism throughout the institution. One of the projects we'd always conceived of in relation to that project was an installation in the Sackler Center utilizing objects from multiple collections. While "The Year of Yes" is officially over, this project certainly has its roots in that moment.

To be sure, this exhibition culls from the entire Brooklyn Museum collection and not just the Sackler Center?

That's the grand ambition but ultimately, we've mostly culled from contemporary colleagues, some from European art, some from photography... at some point in the process, in order to make the show feel coherent around the political imperatives we were focusing on, we did boil it down. For example, we don't have an Egyptian object but we do have works from Africa. We weren't able to truly mine the entire institution the way we did with the "Blue" exhibition, but we were thinking along those lines as a model.

I'm sure it was also a challenge approaching this from an intersectional feminist lens and trying to be as inclusive as possible while still retaining a focus.

I've found that one of the most productive ways of thinking about feminism in an institution is not designating works as feminist or not. Instead, what I try to think about is how feminism as a methodology functions across all art historical fields at this point. For example, in the whole grand history of American art, there are very few examples of works that I'd call feminist, however there is a way in which we can talk about almost any object through the lens of feminist theorizing and feminist critique as it is one of the most important ways of understanding the world since the 1970s.

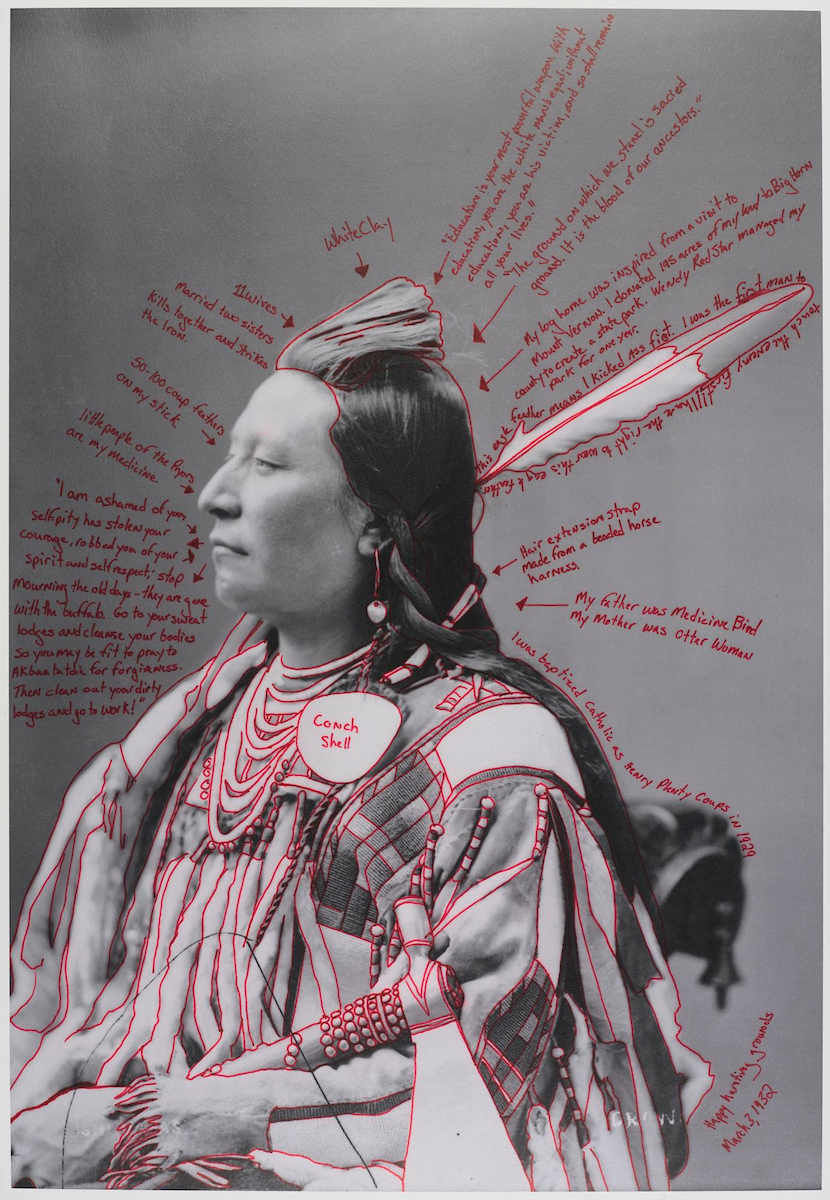

Alaxchiiaahush / Many War Achievements / Plenty Coups (2014) by Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke (Crow)). Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Alaxchiiaahush / Many War Achievements / Plenty Coups (2014) by Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke (Crow)). Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

How many of the works in the exhibition are feminist within their own historic contexts?

I think most people understandably assume that when an artist makes a work, a kind of meaning or intention is endowed upon that work by the artist, which is true, but a work's meaning is also changed by the way we need and want to see it at any given time. I haven't done the math to know exactly how many works in the exhibition are self-identified as feminist but there are certainly a lot. We have many of the big-name second-wave feminist artists from Miriam Schapiro to Nancy Spero and of course, Judy Chicago.

In culling through 100 years of work, we identified common themes and intentions by artists that seem to resonate with current political imperatives. For example, we include work related to sexual harassment that reference the #MeToo and #NotSurprised movements. We have another section called "The Personal is the Political" which is a term that rose up with second-wave feminism in the late '60s and '70s. And then we have a section called "Make America," which explores how feminism has impacted America today and the contradictions that are inherent in what that means in our current political moment. "Resistance and Protest" is a larger section which includes everything from Dread Scott's piece on the impossibility of freedom in a country founded on slavery and genocide to the famous "Silence=Death" posters.

This exhibition's intersectionality lies in the way that individuals are not simply one thing and also how political movements are not just one thing. It's a dialogue that, in 2018, the Sackler Center must participate in.

How were some of these works initially acquired by the Brooklyn Museum? I'm thinking particularly of works by women of color that date back from over fifty years ago. Were these recent acquisitions or has the museum always collected from a diverse field of artists?

One of the things that we really want to touch upon in this exhibition is the idea that museums aren't neutral—they're driven by individuals and they come with their own politics, their own cultural baggage, and their own cultural priorities. Having said that, I do feel that at the Brooklyn Museum, we have some sense of pride (though that feels like too strong a word) in our historical collecting. There are quite a few pieces in this show that have been a part of our collection for some time—a print by Elizabeth Catlett or prints by Alison Saar, for example.

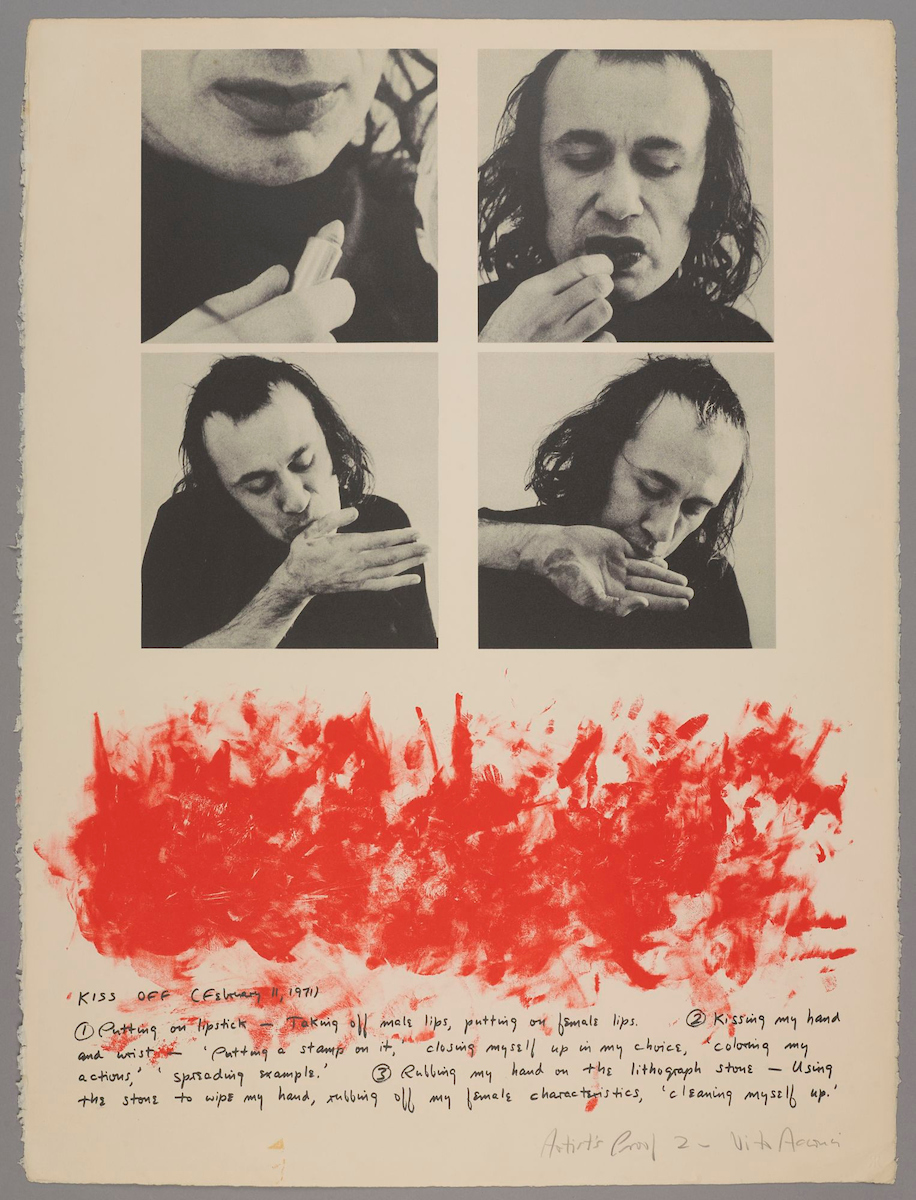

A lot of the works in this show have been part of the collection for a while and haven't been shown in ages—the Vito Acconci prints, these amazing Kiki Smith prints from the early 1990s, the Telegrafica group, a 1992 print of Anita Hill... We also have a lot of recent acquisitions that we're very excited to get out again. We've also received a lot of gifts. For example, the Guerilla Girls gift of a suite of posters is a huge part of the exhibition as well as where the inspiration and title for the show comes from.

One of the really interesting things for me as a curator who hasn't done a lot of these collection shows is that we started out with an idea for this in the simplest terms—what do we really love in the collection that we want to show? From there, it takes shape into something that (hopefully) feels coherent. As in many collections exhibitions, coherence, thematically, ought to be secondary to showcasing important works.

That being said, it's been fascinating and so rewarding to see how these works converse with each other within their curatorial themes. For example, we have works from Käthe Kollwitz's portfolio next to Latoya Ruby Frazier's portraits of her family which creates this wonderful juxtaposition of these women commenting on different political fallouts in their lives, creating this fantastic conversation across 100 years of history and across continents.

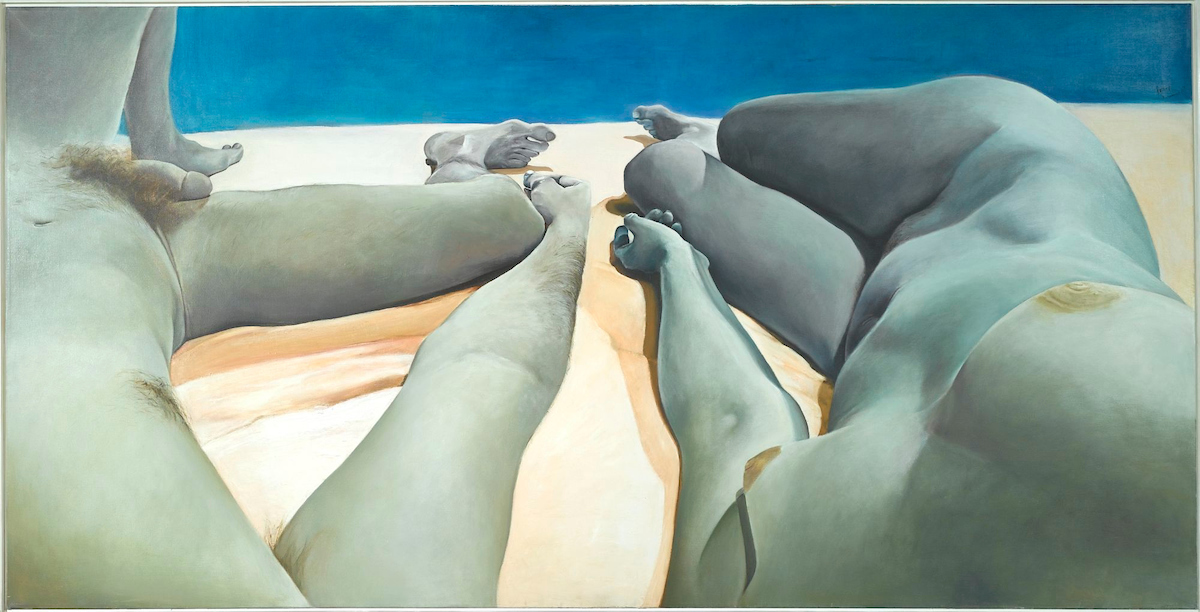

Intimacy Autonomy (1974) by Joan Semmel. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Intimacy Autonomy (1974) by Joan Semmel. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Do you feel a sense of solidarity with regards to this show, thinking about the way women have fought some of the same battles over generations and across cultures?

Solidarity is a great word because there's also the depressing flip-side aspect to it which is that things haven't really changed. Human beings are human beings and the expectation of what changes and how it changes is a through-line, for sure. But I think the other through-line is this very profound sense of humanity in how artists document, grapple with, and express their experience within these contexts and how we can still feel those things across the century.

It's one of the great things the Brooklyn Museum can do with its collection. While institutions and museums are certainly not neutral and are built on ideas that are being highly scrutinized today (and with good reason), one of the reasons why people are interested in historical museums now is because it's a way of digging into history that can be about upending the nationalistic and positivist narratives, and it really gets into critiquing historical assumptions. It's a really valuable thing for a museum to do, even if it's uncomfortable for the museum.

Along with Vito Acconci, I noticed that there are a good number of male artists in this exhibition. How deliberate and intentional was the decision to include works by male artists in a feminist show?

One of the things that I've always said that I really like about my job is that I work in a center for feminist art which is a very different context and mission than a center for women's art. If this was the Sackler Center for Women's art, I'd be a lot less interested in those works. Feminism is about gender, but it isn't gender specific—it's about addressing inequity based on gendered experiences. To quote Eleanor Roosevelt, "When it's better for everyone, it's better for everyone." So the sense that feminism is somehow specific only to women is something that I think needs to change in order for feminism to continue to be pertinent. Not only because men need to be feminist, but because a generation of people is pushing us to understand entire notions of gender construction.

Feminism is a political, social, and cultural movement that focuses on inequities structured on gender but the positive outcomes of gender equity benefit everyone. An artist like Vito Acconci was easy to include because he identified as a feminist. Dread Scott is also included in the exhibition and has had works in other shows put on by the Sackler Center so he's always been involved in an intersectional dialogue about his work. We always need to think about multiple voices across the gender spectrum.

It's also important for us to reframe feminism so that more people see themselves included in its conversation. It's a word that's often used as a cultural shortcut—it's not a perfect term; it has often been rejected. There have been a lot of shows recently—"We Wanted a Revolution" and "Radical Women" in particular—that have been heavily critical of the term and the ways in which second-wave feminism didn't work for a lot of women. I think it's important for us to continue to talk about that and make space for that conversation.

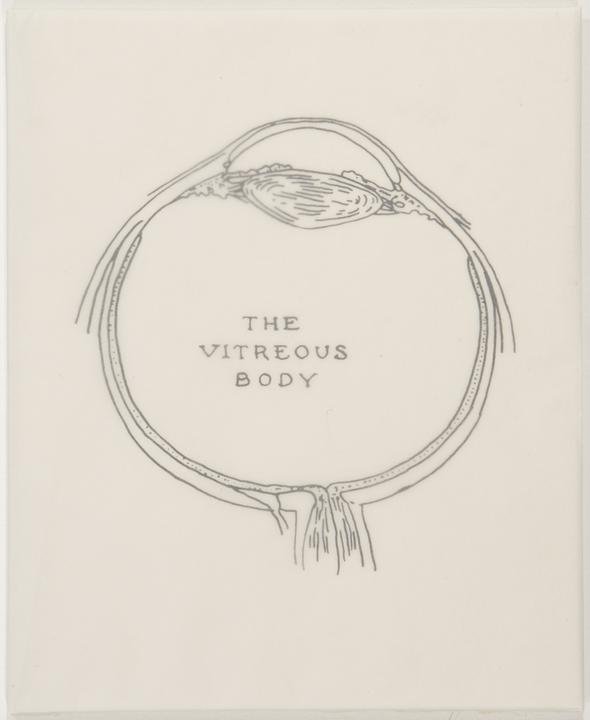

Kiss Off (1971) by Vito Acconci. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Kiss Off (1971) by Vito Acconci. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

After looking through 100 years of feminist art, what would you say is the take-away of the exhibition as a whole?

I think the answer to that question really depends on the audience. For me, as the curator of the Sackler Center, one of the ways I think it's already helping me and informing me is in thinking about what we collect. There's an ironic way in which there's a perception that the Sackler Center's collection should be composed of all the monumental and iconic works of second-wave feminism.

The sad truth is that while most of those women still don't have anywhere near the market parity of their male peers, we still can't afford them. So there's a pragmatic factor in this, but much more importantly, in a social sense, what a show like this teaches us is what it means to build an intersectional collection. This is an opportunity to mine our current holdings to think about that, and that will very much inform the acquisitions that we make and the way that we conceive of and structure the collection in the future.

It is a bit frustrating that a lot of these works in the collection are often only seen under this very specific curatorial lens and context. Why don't we see these works—be they explicitly feminist or not—all the time?

I think the answer to that is that it may be. You can see threads of it in the exhibition downstairs called "Blue," which is another take on mining the collection. Though not overtly political, that exhibition was very much about how to stretch across the vast cultural history represented by the institution. I think we are very much thinking about how you can touch down in multiple installations of collections and have various conversations. That was certainly one of the considerations during the rehang of the American collection a little over three years ago.

I think the next installation of the contemporary collection—which is in the works—will be reflective of that. One of the things that the Sackler Center is lucky enough to be able to do is to really hone in on the politics. That's kind of what we're there for. It'll happen in other places as well, but they're all different. Not only do the exhibitions need to reflect the curatorial voices that are putting them together but also respect the critical changes you may be making to your field.

So many people in the world want to be curators for the next biennial but there's a way in which collections have been largely overlooked but are suddenly feeling very pertinent and valuable. Since the Whitney's relocated, they've done some fantastic collections exhibitions, approaching their holdings the way most would handle a contemporary installation.

It makes me think about how during the '60s and '70s, artists began to establish the method of Institutional Critique as a way to confront museum histories. Now it seems we're at a point where the institutions themselves are taking on that role and holding up the mirror to themselves.

I think that what you're seeing is a generation or two of curators who have risen up through the ranks who were influenced by that. It's exciting for me, who has always wanted to work with contemporary culture within the context of historical objects. To feel like that's where other people want to be now too is really amazing because even ten years ago, it didn't feel that way.

RELATED ARTICLES:

An Introduction to Feminist Art

How Did Feminist Art Begin? A Brief History of Women Rejecting Patriarchy in the Art World

The Other Art History: The Overlooked Women of Surrealism

The Other Art History: The Non-Western Women of Feminist Art