In her new book Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West, published by The New Press, Lucy R. Lippard quotes tourism scholar Dean McCannell: “The best way to keep a cultural form alive is to pretend to be revealing its secrets while keeping its secrets.” This statement seems, reflexively, to sum up Lippard’s authorial project, which ranges in scope from elegiac documentation of landscapes under siege to “escape attempts” from the constraints of contemporary art, all presented in a fugue-like and somewhat elusive text that favors a woven narrative of shifting associations over cut-and-dried disquisition.

Undermining's greater focus is on land use in the Western United States. It's a rhythmic volume: the main text is flanked along the top of each page with full-color images of landscapes, close-up details of adobe, far-off views of private corporate mining sites, and reproductions of works by artists from native communities of the American Southwest, often responding directly to the cultural, political, and personal implications of the radical transformations bearing down their communities. The result is a reading experience that gives the feeling of digging beneath the surface of these images—sifting the dirt, as it were—to touch on land art, landscape photography, tourism, water use, Navajo religious sites, and uranium mining.

As such, the book's scope is broad, and it’s another step in Lippard's continued movement away from the art world—where she made her first major contributions beginning in the late 1960s as a critic, curator, and author of the seminal 1972 book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972—toward something more akin to an archaeology of the American landscape that is both highly personal and universal in scope. If the image projected by Undermining don’t seem to be entirely hopeful about art’s political efficacy against such monumental challenges as corporate encroachment and environmental catastrophe, it is hopeful as a reconciliation between images and politics.

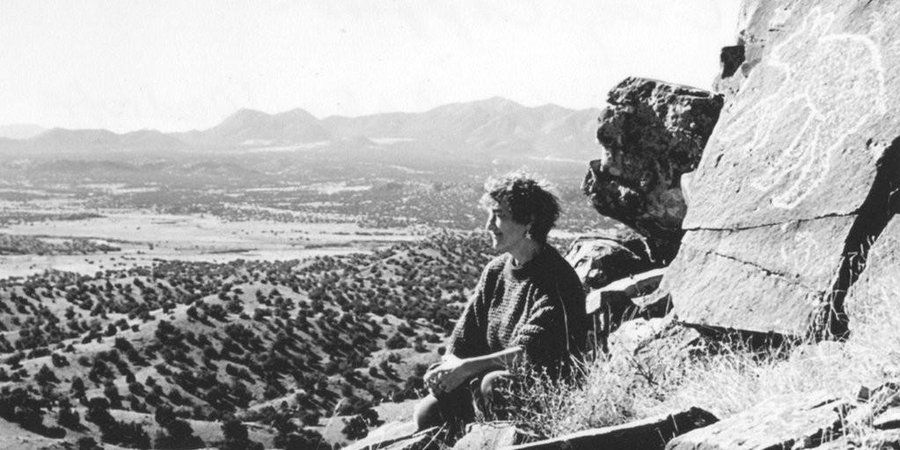

From her home in New Mexico's Galisteo Basin, Lippard spoke with Artspace about her “collage aesthetic,” community as a euphemism, and the importance of social energies not yet recognized as art.

I’m interested in talking about this book in relationship to your book The Lure of the Local from 1997, which takes off from a discussion of the literary or critical history of “the landscape” in Western thought. In Undermining the focus is less on a literary tradition and more on the lived histories of specific places—for example, religious sites of the Native people of the American Southwest.

Well, it’s a juxtaposition of that kind of thing with totally crass capitalist greed. And that’s why I’ve sort of abandoned the term “landscape,” in this book, in favor of “land use.” Because it’s down-and-dirtier.

I’m interested in this idea that there’s not so much a literature to build off of, as there was in The Lure of the Local. What was the process of researching this book like, and how did it come together?

The research was daily rather than delving into libraries—what’s happening as reported in the newspapers, High Country News, locally.... Every now and then I get asked about my methodology, which I don’t really have—I’m not an academic, and I always say my methodology is “one thing leads to another”—that’s really the way I write, and the way I do everything. People are always saying, “So what’s the thesis of this book?” and I go, “Thesis? It hasn’t got one.” It’s just one thing leading to another. I love weaving things together, and finding strange juxtapositions—a sort of collage aesthetic.

I was intrigued by the way images are used in this book, and the design of the whole thing, structurally.

It’s modeled on artists’ books, which I’ve been involved in for many years. I also wanted, for once in my life, to do a small book. It’s really an extended essay. Plus, half of the facts in this book have already been replaced by new facts. The situations are constantly changing. It was supposed to come out last fall, and it would have been a little bit more accurate if it had; I’ve got a giant carton of updates that I’m never going to use, but can’t resist keeping them. So people should realize that this is not supposed to be a textbook on what’s going on in mining and all the other subjects—it’s primarily a suggestive text.

Well, for example, the fact that there are no maps anywhere in the book—

That’s interesting, I never even thought of putting a map in!

And you have many images of artworks by artists from the Native American communities you’re discussing, as well.

It’s all inspired by The Lure of the Local, and the whole idea that you should take responsibility for the place you find yourself.

Do you see it as a sort of a sequel to, or an update of, the ideas from the earlier book?

Not really, it’s a really different book—it’s coming from a different place in my life. That was almost 20 years ago.

You’ve lived in New Mexico for over 20 years, but before that you were very involved in the activist art community in New York in the 1960s. I’m wondering how the activist community in New Mexico compares to the New York activist world you left behind, which sort of dissipated in the early ’90s.

That’s one reason I left. But yes, it’s totally different—it’s much more local and community-oriented given my life in New Mexico. I’m involved in community planning, watershed restoration, things I probably would not have thought of as being “activist” in the ’60s. Environmentalism used to be “soft politics”—I think I said that in the book—but climate change has upped the ante. It’s obviously crucial now. I edit my community newsletter, which I’ve done for 18 years. That’s part of my activism here.

We’re facing three huge issues in the area, one very close to us and the other two a few miles away. One is that they want to ship crude oil into this tiny little town, the next town over from us—it only has one road, and that’s a dead-end road—and they want to bring oil tankers in and transfer crude oil into the railroad tankers right there. It’s just crazy, with all the oil spills that have been going on. So we’re up against that, and then a possible new gold mine in the mountains that are just to our west.

Then to the northwest there’s another proposed gravel strip mine at the historic gateway to Santa Fe, which depends so heavily on tourism. All these things are pending right now around this town of 250 people, so the activism is absolutely necessary. But it’s very different from wheat-pasting, from being out in the streets. The one time I tried wheat-pasting in Santa Fe, at the beginning of the Iraq War—portraits of Middle Eastern people, women, children with no texts—they disappeared immediately.

Do you think it’s a kind of activism that doesn’t really exist in New York anymore?

Oh no, I think it does exist—in the whole Occupy movement, the Arts and Labor group, and those kinds of things; it’s all there. But it is a different community, obviously, than it was in the ’60s. The ’80s were also very different from the ’60s—I spent most of the ’70s on feminist activism, and the ’80s were different from the whole antiwar community stuff in the ’60s—so it’s all always changing.

Speaking of the early days, when you were in New York you worked at the Museum of Modern Art for a while.

I was a page in the library, my first job out of college, my only real job ever. It was for a year and a half, I think.

At that time, there were a lot of artists working at MoMA, and it was a much smaller place than it is now; it was sort of an incubator for a lot of activity in the art world.

It was a real community, it was an interesting place. Not activist at all, but there was activity. But then I ended up, of course, picketing the museum on several different issues.

Do you think that there is an equivalent sort of place in art now, within or outside of the museum world?

I just don’t know. I’m not that tied into the art world anymore. I live locally now, and I go to New York once or maybe twice a year for a few days. I have friends who let me know what’s going on. But that whole DIY movement seems to be happening in community gardens, and all the Occupy stuff too—there’s a certain amount of reinventing of the wheel going on, I think. But if it needs reinventing, then go for it.

A lot of the images and information in Undermining comes from the Culver City, California-based Center for Land Use Interpretation [CLUI], which is run by Matthew Coolidge and Sarah Simons. I’m wondering if, in a way, you think of that as an artistic project, or what interests you about that particular organization.

I’ve always loved CLUI. They really do some amazing stuff, and I don’t know if it makes any difference whether they’re “art” or not. I’ve called them the most interesting “conceptual art-or-not” going on now. It certainly has become an art project, in a certain sense, and I guess Matthew meant it that way, though I think he studied geography and film. But it extends way over the borders between art and non-art. For years I’ve been babbling about social energies not yet recognized as art, which is something I wrote in the ’70s and still say all the time. It interests me a great deal, and CLUI exemplifies it. As my partner says, CLUI “trumps cynicism.”

There’s a lot of interest, in art, in “social practice” and socially-oriented projects right now. But I often wonder how political those projects can really be, or at a certain point, once they hit a certain level of buzz within the art world, whether they become neutered.

But that’s one wonderful thing about CLUI; they’re not just pointed at the art world, so they can have a broader effect. Whether they’re liked or disliked or whatever in the art world doesn’t really make a whole hell of a lot of difference, because they go beyond it.

Are there other similar projects or particular artists you’re interested in at the moment? You mention Trevor Paglen in the book.

Yes, Trevor’s wonderful. I’m also interested in more fantastically-oriented stuff, like Futurefarmers, Amy Franceschini and Michael Swaine, Mary Miss’s CaLL project, a lot of what’s going on in Detroit—too much to list.

That leads me to Land Art, which you have a very critical take on in Undermining. You say “much land art is pseudo rural art made from a metropolitan headquarters, a kind of colonization in itself."

I originally published that take on Land Art in the ’90s, in a talk at Marfa.

You also talked about it at the Creative Time Summit last year, and got some applause. I’m interested in this idea of art-world tourism in rural places, because I thought of, for example, Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument last summer, which was basically an installation in a housing project in the Bronx. I think it had some of the same sort of issues—as the art world’s collective field trip into another community

Well, that’s been going on ever since I’ve been in the art world, since the ’60s certainly. It’s a very fine line, and I hate to discourage people from going out and doing things like that because, in the end, at least it’s something. It does open certain eyes in the art world, but the real world tends to be a lot more skeptical about these kinds of things—and cooptation by the mainstream is always a danger. It’s hard to know how to avoid it. I’m just trying to finish this lecture for Detroit, and the art scene in Detroit—the little bit I know about it—and things are riding a similar kind of ambiguous wave there.

What about the distinction between land art and public art in a project like Hirschhorn’s? Do you see a difference?

Well, for example, take the work of Nancy Holt, who was a close friend; she always thought of herself as a public artist, and I sort of disputed that. But then some of her work was very successful as public art, so there are artists who do both. But there are also artists who seem to care about the audience and people who don’t—let’s put it that way. All of us who advocate for this kind of publicly-engaged art tend to kid ourselves about how effective it can be. Some of it really works. Look at "LAPD," John Malpede’s street project in Los Angeles; that really is immensely effective. A lot of Suzanne Lacy’s projects are, too. But now “social practice” has taken on sort of an academic tinge, as Rick Lowe pointed out at the Creative Time Summit.

How do you define effectiveness, in these kinds of projects?

I always say art can’t change the world, but it can be a very strong ally for unconventional ways of looking at the world. Effectiveness is usually consciousness raising. It’s not like, “Now we’re going to go out and have affordable housing right now.” It raises people’s consciousness about the issues, and about what capitalism is doing to all of us.

I wonder if this is related to your idea of “sense of place” as immersion, which was another idea that also came up at the Creative Time Summit. Do you think that actually living in a place or within a community is a prerequisite for having an active or effective role, in terms of activism? Especially continuing with the example of the CLUI as a project that is about the local, in a way, but is also decentralized.

CLUI does do a lot of stuff about Los Angeles, and if you follow their stuff about LA and you live there, you sure know a lot more than you ever did before. But it is, also, expansive. When they get into something, they really do an incredible job of in informing you about a place you may never have been. When I talk about immersion, I’m talking about where people live, and, everybody lives someplace, but very few people get that involved in the place that they live.

I wasn’t that knowledgeable about where I lived in New York. I knew something about the history, and so forth, but I lived all over the place. I wrote something called “Seven Stops in Lower Manhattan,” which I think I mentioned at the Creative Time summit. It was a really interesting experience—to return to the various places I’d lived and to see what had become of them. They were all very different than they had been when I lived there. “Immersion” was something that came up out of the ground from being in the West a lot.

Everyone lives in a place, or a community. I think the word “community” has been misused; it’s become a sort of euphemism for a poor, neglected neighborhood—but a lot of those neighborhoods are actually not real communities, and that, ironically, is one of their major problems. When community activists get going they can help create a community, which I think is one form of effectiveness.

What about the role of the Internet, or of new media, in all of this, as a decentralizing force? CLUI and LAPD are both Internet-supported, if not Internet-based, projects.

People are always asking me about this. I’m a luddite—I’ve finally learned to use the Internet to some extent, but I don’t look at websites, I don’t surf at all. I just don’t have the time.

Printed Matter, of course, is concerned with one variety of a democratized distribution of art, of which utopian conceptions of the Internet today are reminiscent.

That seems so old-fashioned and so specific now—the Internet is just such a vast, crazy thing. I was trying to find an artist from Detroit now based in New York, for this lecture I’m putting together. I needed an image of his work, and I looked him up on the Internet and found him, but I couldn’t get any further than that because I had to pay 15 bucks or something to find out his e-mail address. I’m sure there’s a better way to do this, but the point is I’m always coming up against that kind of thing and quitting the Internet in disgust.

The Net is not necessarily a good replacement for the kind of material that Printed Matter was originally, and still is, about disseminating.

No. Definitely not. But in the early days of Printed Matter we had this dream that artists’ books would be in drug stores and airports and that was sure pie-in-the-sky. The audience remains pretty specialized, but I’m amazed at the vast number of them that exist now. The store is jammed to the gills with wonderful stuff but you have to give yourself plenty of time to browse it. You have to have some idea of what you like.

And meanwhile, art books have become a whole other thing—it almost seems as though books have had to become more expensive and fancier and more complicated as a result of having to compete with the Internet.

That’s why I was so pleased to have Undermining be a small book. I don’t quite see why exhibition catalogues, for instance, have gotten so grandiose, why there have to be several authors, overlapping texts.

It has a great a rhythm to it, too. Could you talk about the design of the book?

It was roughly modeled after an artist’s book. I was very involved with the whole design process—I told the publisher when I presented the book, “This is what it’s going to be—pictures that go all the way across the top, text in the middle, and captions all the way across the bottom.” Then, of course, I had no idea what I was getting into—the designers didn’t quite get it at first. When I got the first galleys it didn’t look like what I wanted and the pictures didn’t match the text. The word counting, the specs, was a nightmare because I wanted parallel verbal and visual narratives. So then finally they just sent me little hard copy thumbnails of every image, and I just rearranged the whole book and put them where I wanted them.

So it was a very technical process.

It was part of the writing of the book, really. I always get a visual image of a book before I write it, of the title and the image—what it’s going to look like.

In the end, Undermining doesn’t seems entirely hopeful about the political efficacy of much existing contemporary art. Is that a fair takeaway?

Again, I don’t want to denigrate some of the great stuff artists have done. But I just wish there were more energy going into the causes rather than the effects. More real, hardcore, nasty investigative reporting kind of stuff in visual form. It’s all grist to the mill. We’re all trying.

In other words, there’s a lot of room for improvement.

Yes—or at least for new angles. There’s an awful lot out there I don’t know much about—I have piles of files and if I ever had the time to go through all of them carefully I’d be able to answer this question better. Also, my last couple of books have been about archaeology and history, so that’s a whole totally different field that I’m about to get back into now that this book is done.

What are you working on now?

I did a book in 2010—Down Country: The Tano of the Galisteo Basin, 1250–1782—mostly on the indigenous remains in the area. Ed Ranney went out and photographed with me for years, and I just wrote the text for a book of his on the Nazca Lines. So, anyway, the next book is going to be about the village itself from around 1800 to the present, which is going to get me in a lot of trouble. As I get old, I’m getting closer and closer to home.