One of the most prolific artists of the 21st Century, French-American artist Louise Bourgeois created works embodying a singular language in Feminist expression—one that was unflinchingly personal, corporeal, and sensual. While she never explicitly declared herself a feminist artist (she has described her work as being "pre-gender"), her explorations of unconscious sexual desires as a woman were pioneering and authoritative and in 1982, she became the first woman to receive a solo retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

Culling from the childhood traumas of her father's infidelity, the artist engaged in a lifetime of reckoning with themes of gender roles, insecurity, fragility, pain, temporality and memory. Bourgeois passed away in 2010 at the age of 98 having never retired from making art, leaving behind a personal legacy full of compassion and devotion (the last year of her life was devoted to using her work to fight for LGBTQ rights and marriage equality).

This month, the artists ouvre of printed work makes a posthumous return to the MoMa in Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait. Bringing together some 220 works, the exhibition celebrates the museum’s archive of Bourgeois prints and displays them in relation to her practice at large. For Bourgeois, no medium took any precedence in her practice; in her own words, they all "say the same thing in different ways."

In the 2003 Phaidon monograph Louise Bourgeois, critic Paulo Herkenhoff asks Bourgeois about rebelling against her controlling father as a political act, about her rejection of term "surrealism" in favor of "existentialism," and about making sculptures that "deflate the male psyche as a structure of power"—in this excerpted interview that is just as bold and idiosyncratic as the work itself.

---

Louise Bourgeois posing with Spider IV (1996)

Louise Bourgeois posing with Spider IV (1996)

Louis Bourgeois: Let us get something clear before we begin. In general I don’t need an interview to clarify my thoughts. It is absurd, a pain in the neck! Interviews are a process of clarification of other people’s thoughts, not mine. In fact I always have to know more about you than you know about me. All the same I like to be crystal clear when I speak. I like to be a glass house. There is no mask in my work. Therefore, as an artist, all I can share with other people is this transparency.

Paolo Herkenhoff: You have always kept a diary, ever since you were a child. Moreover, you write on the backs of your drawings and you take notes. All this writing must have a very clear meaning for you.

I use these writings for clarification. I worship transparency. I search for transparency. You see, there is no mask in my work. I am perfectly at ease with language, so much so that when I married someone who did not speak my own language, it did not make any difference to me. I learn your language, you learn my language. In the end it does not matter, because the language of the eye, the intensity of the gaze and the steadiness of that gaze are more important than what one says. Language is useful but not necessary. You cannot fool me in the visual world, but you can get the better of me in the verbal world.

Jerry Gorovoy (Louise’s assistant of twenty years): When Louise is writing it is very spontaneous. Very direct. Her writing flows so tightly, as if in direct contact with the subconscious. I’ve seen Louise write something on the back of a drawing and and when she reads it again she sometimes can’t even remember where it came from.

I can tell you the six key events in Louise’s early life: the first is the introduction of Sadie, the children’s governess, into the family and Sadie’s ten-year relationship with Louise’s father while living in the house. The second is the death of her mother in 1932. The third, her marriage to Robert Goldwater in 1938; the fourth, their moving to New York. And then there was the adoption of Michel in 1940 followed by the birth of Jean-Louis that same year.

Louise Bourgeois with her parents Louis and Joséphine c. 1915

Louise Bourgeois with her parents Louis and Joséphine c. 1915

You have spoken at length about the effect of your father’s authoritarian role over you and your family when you were growing up. Since he was so controlling, how did you assert yourself in relation to him?

Probably the best answer to that question is to speak of my trip to Russia in 1934, at the suggestion of my instructor at the Sorbonne in Paris, Paul Collin. Ostensibly I went to Russia to see the Moscow subway. I went as a reporter for L’Humanité, I was going to publish an article on the subject. The trip was an act of political independence.

Were you a Marxist? Did you belong to the Communist Party?

I mean political in the sense of rebellion against my father. The trip was an investigation and an expression of that rebelliousness. My independence was due to the fact that my father did not have to pay for me. You know, to be supported by your father is a great responsibility.

I do not remember feeling anything at the time. I was just moving, moving on. You know, it is very difficult to remember—even if it is indispensable, to remember. Memory has become so important to me because it gives me the feeling of being in control, in control of the past.

You said that forgetting bothers you, that it is a suffering.

Yes. It is tiresome to look and not to find. It proves the impotence. It is a manifestation of impotence.

What are your reactions when you feel impotent?

Quand les chiens ont peur, ils mordent [When dogs are afraid, they bite]. If you make me impotent, I reach for my dagger. There is also the anger of understanding, the anger of travelling, the anger of pardoning.

Your print What is the size of the problem? Confronts two apparently similar and yet different zones? Is it an unfaithful mirror?

The print is related to the ambivalence of perception. The printing was done after a drawing and a quotation from the 1940s. Ambivalence is for the emotions. Ambiguity is for the brains. [Louise reaches for the tiny bottle of Shalimar perfume that she always keeps at her desk and opens it to enjoy the perfume.]

Evanescence and stability are the ground of some of my feelings. The fear of losing—this is very important for me. Evanescence means a come-and-go. The evanescence of memories is very important. You have souvenirs which appear to you and then all of a sudden disappear. Evanescence gives birth to the fear of losing. I want to give my work permanence.

So, Louise, you fight between evanescence and permanence.

A spiral is also a metaphor for consistency in my drawing. The soul is a continuous entity. I am consistent. You can trust her because she is consistent. If Louise tells you that she loves you she is not likely to change her mind.

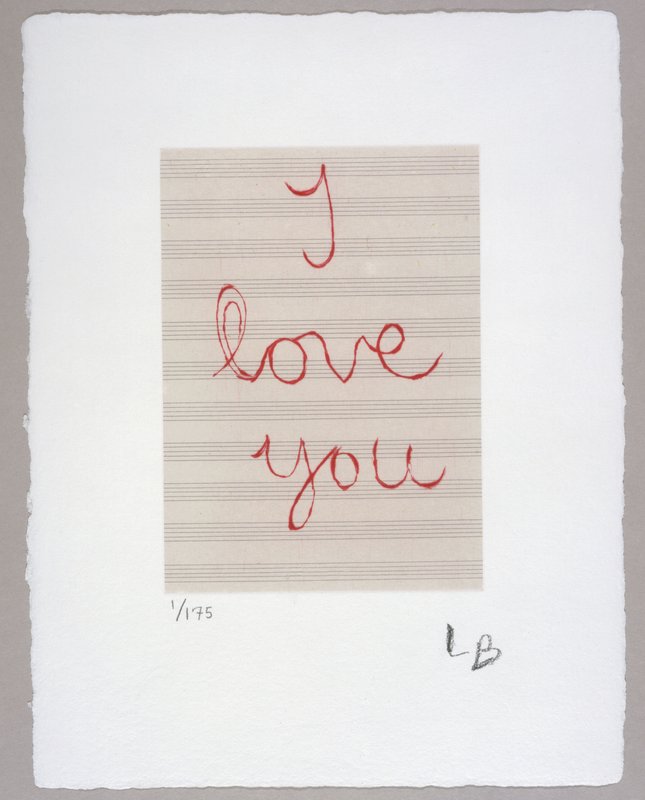

I Love You (2007)

I Love You (2007)

Fear is the thing? The result? Your work resists the idea of suffering. Does suffering ever have something to do with sculpture?

No, because it is too vague. How can art save someone from suffering, from insanity? You have to ask a doctor. I can not answer that because I have never been there. I carry my psychoanalysis within the work. Every day I work out all that bothers me. All my complaints. This way there’s always a component of anger in beauty.

Paulo, let me write in your book.

[She writes in red pen:]

I do

I undo

I redo

[Underneath she draws a large circle with the phrase ‘the pregnant O’.]

That is the beauty of the drawing. Drawing opens our eyes and the eyes lead to our soul. What comes out is not at all what one has planned. The only remedy against disorder is work. Work puts an order in disorder and control over chaos. I do, I undo, I redo. I am what I am doing. Art exhausts me. Yet I work every day of my life.

Do you lose the notion of time when you are carving or drawing?

Of course you lose track of time. You follow the pleasure of the activity of drawing. You do not care what the result is going to be. All the connections are unconscious. You do not know where you are going to end. It is a journey without an aim.

The unconscious brings up Surrealism, a term you reject when applied to your work.

I was not a Surrealist, I was an existentialist. That is the magic word. I love the literature of Albert Camus. I despise nihilism, however.

You are an existentialist who fights back.

Perhaps. It is simply that looking is my job. But I am afraid of looking at things that confuse me. To be confused and not know you are confused is the definition of stupidity. Here you see my fear is not fear itself but the fear of being met by confusion. That is why I prefer images. An image never betrays you; if you look hard enough you will make order out of disorder. When I witness mental confusion in another person I fear contamination. Let me live in a world of image and I will never complain.

What do you think about the state of the visual world today? What do you think of the use of new media, such as computers, in the visual arts? You seem scared of computers.

I don’t even know what a computer is. I don’t think about it. It does not help me. It does not bother me.

So, what comes to your mind when I say ‘the Web’?

Oh, I think of a spider’s web, of course. She weaves her web. You know, Ode à mére has been a very important subject because it has been at the basis of all my spiders. It relates to industriousness, protection, self-defense and fragility. The spiders I have made over the last decade have been a big success. And I do not object to how such a statement might sound to others, because success is sexy!

Maman (1999)

Maman (1999)

Is art not an obsession?

No. In art one must avoid obsession. Because obsession is a state of being. It is an unfortunate state of being. If you are possessed by an obsession you cannot function. Some artists are successful, non-pecuniary and yet very good. Some are derivate. Some are original. Ultimately to be an artist is a privilege; it is not a métier. You are born an artist. You can’t help it. You have no choice.

What is your process of creation?

Conception and realization of art. There is not one without the other, but the conception comes first. I can be contradictory from one piece to the other. The realization of a work may take place two or three years after the conception.

Is there an emotion one can be possessed by and still make art?

Yes, compassion. Without compassion there is no work, there is no life, there is nothing. That is it. But at the same time art has nothing to do with love, it is rather the absence of love. To create is an act of liberation and every day this need for liberation comes back to me. In terms of making a statement in art, which do you prefer, to scream or to be silent? It depends on what you want. If you want attention, you scream.

The Couple (2003)

The Couple (2003)

In terms of body language, you say that the eyes play an important role. How do you relate that to art? Is making art a body language?

It is the answer to a need. Actually, you don’t know what the need is until after the work is done. With words you can lie all day long, but with the language of the body you cannot lie.

Is the body an existential sculpture?

Oh yes, our body is being influenced by our life. And yet our body is more than the sum of its parts. We are after all more than the sum of our experiences. We are as malleable as wax. Descartes wrote about wax. We are sensitive to the souvenirs of what has happened before and apprehensive to what is going to happen after. Consequently, everything is energy. I experiment with people who are like iron—who are not malleable at all. I have no confidence in my ability to manipulate other people. The Moebius strip is a fascinating topological structure. It stands for the dance of desire. However, I represent the sexual encounter from the point of view of the woman. She won’t let it go.

Certain objects incorporate the drives in your sculpture, such as clothing. Louise, is there a basic language of clothing?

We must talk about the passivity and activity of the coming and going of clothes in one’s life. When I come upon a piece of clothing I wonder, who was I trying to seduce by wearing that? Or you open your closet and you are confronted by so many different roles, smells, social situations. For me, clothes are always someone else’s. That is to say that I have never bought or made my own clothes. Never, never, never. Clothes are a gift, a choice, a test of the presence of a man to a woman. They are a test of taste. Does he see me like a balloon? Does he see me like a sylph?

Cell (Clothes) (1996)

Cell (Clothes) (1996)

Why are you interested in sleepwear?

Because we spend as much time asleep as awake. In other words, we are wrapped in cloth as we sleep as much as we are wrapped in cloth during the day. Sleepwear for me means all bed wear, that is to say, bed sheets, linens, pillowcases and very special blankets. The clothes I include in my work belong to the artist, the maid and to friends. Is is very inclusive. "Friends" means anybody who has visited the house and who, by inadvertence, left an old book, a scarf, or galoshes, and by doing so enters the "collection." For example, Le Corbusier forgot his glasses.

You confront the hierarchy between male and female. Thus, in your work hysteria applies to both genders and its psycho-organic arch is made by the contractions of the male body in Arch of Hysteria (1993). This disrupts the scientific principles of early psychiatric technology, from Jean-Martin Charcot to Sigmund Freud. What does it mean for you to point out the rational, emotional and erotic limits of the male and the fragility of men? In your extensive body of sculpture very few works deal with male anatomy: Fillette (1968), The Destruction of the Father (1974), Portrait of Robert (1969) and Arch of Hysteria.

My intention is to put down, debunk the abstract male, whose image is constructed by society. In Banquet / A Fashion Show of Body Parts (1978) I wanted [to present] an art historian, a critic who was also a man. Therefore I chose G., a specialist in Henry Füseli. He went too far in making fun of himself. There is the ridiculous male. Most of those sculptures deflate the male psyche as a structure of power. Mamelles (1991) points out that Don Juan’s need to sleep with many women meant an inability to love. Did Don Juan sleep with older women? Isn’t "Don Juan complex" in the dictionary? Or "Don Juan syndrome?" Syndrome is a very, very good word. It is the concurrence of a set of symptoms, a repetition. That shows a pathology.

Fillette (1968)

Fillette (1968)

Architecture is a very complex issue in your memories and work; let's focus on one aspect of that. Quite often you mention the maison vide and the femme-maison as referring to the challenges of domesticity.

I find the duty of running a house almost overwhelming. You have to be so practical, so patient, so energetic and resourceful. Remember that I have done many works representing myself as the femme-maison. The maison is quite symbolic as architecture, the subject and life. I made a work called Hommage to Bernini (1967). It was a homage to a sculptor whose work was full of folds. There was no emptiness [in this work], not an inch which was not filled with folds, as if emptiness was Bernini's enemy. The maisons vides [empty houses] are a metaphor for myself. The maisons vides are houses where I have lived or worked in the past; they are all empty now. Therefore they are the constructions where we exist; the architecture of our life, that is, the different places where we exist. So this is the history of a life. I try to make them come out of the shadows and make them appear under the light of the present. Life is organized around what is hollow.