After a nine-year absence from the New York exhibition circuit, the painter and sometime gallerist Lisa Ruyter has at last returned from a decade-long stay in Vienna with a series of vibrant new works. Spanning Eleven Rivington’s two Lower East Side spaces, the show represents both a departure and a return for the former expat: Ruyter’s paintings take images from the celebrated Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information photo archive as their basis, combining her process of painting large-scale copies of photographs in flat neon colors with appropriated imagery for the first time since the early '90s.

Ruyter has selected images of scrapyards and women in patterned dresses as her main subjects for this group, creating more or less faithful reproductions of the documentary photographs that nevertheless edge towards abstraction (something the artist herself claims she doesn’t believe in). Artspace met with Ruyter at the gallery's 195 Chrystie Street space to discuss her choice to come back to the U.S., the challenges of running a successful exhibition space in Vienna, and why appropriation is no longer "punk."

This is your first show in New York since 2006. Why the long absence? And what brought you back this time around?

The main reason is that I don’t live here and haven’t been living here. I haven't had a gallery here since that show in 2006. I’ve lived in Vienna for about 10 or 11 years, and the way the work was going it became very important for me make something about American identity, especially as an American living in Europe.

I had done a show that was indirectly about Vienna, which you might never know from the subject matter—the works in that show were from photos that I took at the International Atomic Energy Agency, which is based in Vienna—but could perhaps tell from its internal mode. That whole project was super intense. It was really about questioning: What is the location of the artist, and what is the relationship between artists and journalists?”

When everything was crashing in 2008, my reaction was that I wanted to do something about what’s happening in the U.S., about how quickly people in the U.S. lost everything because of stupid financial things. When I came here to research that I went to California because it was the hardest-hit spot, and I quickly realized that I’m not that kind of photographer or journalist. The exchange between photographing people who are having a tough time and what I was doing just felt really fucked up.

On another level, I’ve shown all over the place, and I just realized that it’s time to consolidate if I really wanted to build and keep working. European galleries really look to the American galleries to lead, so without an American gallery I was kind of missing something as far as being able to keep my studio going financially. It was really important to come back here, for every reason.

Louise Rosskam: Washington, D.C. Canning class conducted by the Mother's Club at the Barney neighborhood houses, Southwest Washington, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

Louise Rosskam: Washington, D.C. Canning class conducted by the Mother's Club at the Barney neighborhood houses, Southwest Washington, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

What drew you to the Farm Security Administration archive to express these ideas post-2008?

I had wanted to make appropriations from that archive for a while, because these photographers—Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange—are the ones I always looked at when making my own pictures. They were just in the back of my mind as to what a photograph is, somehow especially Walker Evans with his very frontal, almost staged compositions. I realized that this was actually the perfect time to appropriate those images. I was kind of fed up with my own photography in any case, thinking that with so many people putting so many photos out on the Internet the act of photography feels like such a useless activity, something completely different than it did 20 years ago.

That archive and especially the early part in showing the Depression in the ‘30s—the whole Dust Bowl thing—had such an uncanny resemblance to what was going on in 2008 and 2009 with the mortgage crisis, and with economic polices leading to ecological disasters. The Farm Security Administration is what put industrialized farming into place in America, and yet our idea of those photographs is that it’s about the identity of America being the small, individual, immigrant farmer—things that never really existed. Exactly the opposite of what it was selling as American identity is what came out of it. That’s what started bringing me back to America.

Is this your first time working this extensively with appropriated images?

This is my third show in this series, but it’s not really the first time because the very early work I did was using found images. In fact, this show is pretty directly referencing early wall drawings that I showed in a group show curated by Bob Niklas in Vienna in ’93. They were all found images, and I figured out how to put them together by outlining them. I thought there was this hierarchy of images—you "believe" a photograph differently than you "believe" a diagram, which is different from how you "believe" an artwork. I had this archive of images that I wanted to work together, so I outlined them and found that this was a really great way to put them together. At the time, I always talked about it as representing the kind of authorless architecture that was happening with satellite systems, radio, and TV. I looked at them a couple of years ago, and realized, “Oh my god, I was predicting the Internet.”

Eventially the found images started disappearing from the paintings. I found it really hard to find landscape pictures, so I started taking my own photographs of landscapes, mostly of New Jersey’s weird industrial suburbia where I was living at the time. At one point I realized that a photo I had taken of a fake deer in somebody’s front lawn in New Jersey said everything that I wanted to say about identity. It was my own photograph, so there was no issue about appropriation. I felt like I had been using these appropriated images without really talking about appropriation at all, which was of course becoming a very big thing at that moment.

John Collier: Fort Kent, Maine (vicinity). Salvage drive for scrap metal, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

John Collier: Fort Kent, Maine (vicinity). Salvage drive for scrap metal, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

Why have you moved back into using appropriated images for this series?

I thought it was a really great time to start appropriating these images, because appropriation as a mode of representation has completely changed in meaning in the last 20 years. Jeff Koons looks practically Mannerist now—it’s not at all what it meant 20 years ago. There’s nothing punk about it anymore.

The Farm Security Administrationarchive is generally without copyright restrictions, so I can’t even engage that issue to begin with, and it had everything I wanted to deal with in terms of subject matter. I keep thinking about these early ‘90s works now that I’m working with this archive, because those are kind of about archives and this is about how this archive has functioned over the years—it’s still going strong, and so many people are using it. These works themselves feel super honest to me, almost earnest.

Half of this show is made up of the photo-based figurative paintings you’re well known for, while the other half is images of salvage piles, both sourced from the FSA archive. What can you tell me about the latter group?

The first two shows in this series used more famous images in order to establish that I’m working from appropriated images. Nobody would know otherwise—I could have made practically every show I’ve made up until now using this archive. Every time I use this archive I use the same title, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” which is itself appropriated. It’s an indicator, but the repeated use of it also becomes a kind of narrative, in a sense.

The scrap piles are the result of looking through the archive to find a fixed image that looked like those early ‘90s collage pictures. They look uncannily similar, and the photographs look like abstract paintings, in a way. I don’t believe in abstraction. I just don't think that it exists. The whole point of abstraction is that it’s ephemeral, like color—it doesn’t really exist on its own.

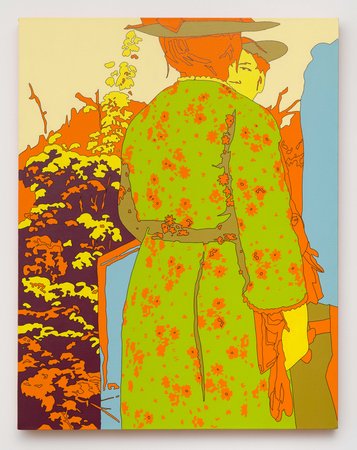

Jack Delano: At a funeral of a member of an old Greene County family, the Bosswells, Georgia, 2014. Coutesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

Jack Delano: At a funeral of a member of an old Greene County family, the Bosswells, Georgia, 2014. Coutesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

That’s a really interesting way of thinking about it. What then, in your estimation, are we looking at when we look at a so-called abstract painting?

We’re looking at that object. Think about a gestural painting—it’s not gestural itself, it’s a representation of a gesture. You’re not seeing a gesture, you’re seeing brushstrokes that are a representations of gestures that were made. The gesture is not what was left behind—the gesture is the movement when it was made. A gestural painting is a representation of those gestures. It is not gesture itself. I think its an essential mistake in our world, mistaking representations for actual things, like money for example.

Of course, everybody is talking about abstract painting now, so the scrap works are a little bit tongue-in-cheek, plus they were really fun to make. I did the black-and-white one after I knew I was having this show in New York, because the last show I did in New York was all works using the same paints that are in that painting. It’s even the same pots of paint as before.

John Collier: Fort Kent, Maine (vicinity). Salvage drive for scrap metal at 4:30 p., 2014. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

John Collier: Fort Kent, Maine (vicinity). Salvage drive for scrap metal at 4:30 p., 2014. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

This show spans across two gallery spaces, but includes only a handful of large-format paintings. Why work at this scale?

I keep thinking that these giant mega-gallery spaces are kind of destroying any chance of a large painting being theater. They’re all the same, with no context to them whatsoever. I’ve always made large paintings that haven’t been shown so much, and all these works are painted at a dimensionality that I want to bring back into the work. I don’t know if that will actually happen, or if it’s just an idea that’s going to guide the next pictures that I make. I see a lot of painters dealing with the same topic, and I just want to change the markers a bit.

Switching gears, you’ve been described as an “artist-practitioner” for your work with your different galleries, including Team Gallery, which you founded in 1996 with José Freire, and your own itinerant Galerie Lisa Ruyter. Are you still involved in running a space?

At the moment, no, because I can’t afford to do that and be here at the same time. I had a space in Vienna that was super competitive commercially, but I made a decision in 2006 to not do art fairs because I felt that this was destroying any reason for me to have that space in Vienna. Art fairs were the one place that I felt that my being an artist was compromised.

Why did you feel that way?

It’s because of their power. It completely neutralizes anything you’re trying to do as a gallery. You have this moment where you have the possibility of making a statement, but then you have to run by these rules that are so fixed. We have rules in Vienna that are also fixed, but the reason my gallery was so successful is because I had no clue about the way things work there. When I moved there I didn't speak the language and knew three people. I didn’t know that there was this rigid distinction between a commercial venture and something that would be paid for by the Ministry of Culture, like the artist-run off-spaces that are a big thing there. It’s starting to happen more now, but at the time nobody would ever review an artist-run space for the paper. It’s a real cultural difference. There, it’s almost like the space is a part of the medium in a kind of weird medium-specificity theory applied to exhibition spaces.

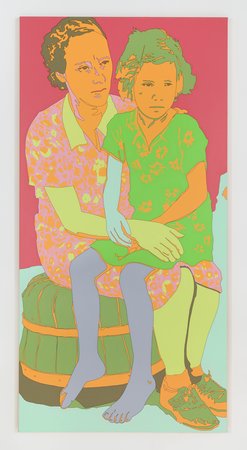

Russell Lee: Mother and child of agricultural laborers encapmed near Spiro, Seqouyah County, Oklahoma, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

Russell Lee: Mother and child of agricultural laborers encapmed near Spiro, Seqouyah County, Oklahoma, 2015. Courtesy of 11 Rivington, NY.

What was the catalyst for you pausing your career as a gallerist?

I ran another space later that I tried to do without giving it a name. After telling all these people that they should open a space that only shows women artists, I thought, “Why am I telling other people to do this? Maybe that’s my way to do something without getting caught up in the competitiveness of the commercial thing.” I did a program in a space that I had gotten but didn't know what to do with. It was a really cool program, in part because when people came to visit they saw me and not some guy who was working for me.

The collectors stopped coming after two shows because it was too much of an out-of-the-way space, but then again I was also too commercial because the place was too nice—in other words, it was too professionally run to get money from the Ministry of Culture. There’s a kind of mentality that says, “That person must have money, so why should we support their space?” I tried to push it as far as I could, but let’s just say that the conditions were not such that I could continue. A space should pay for itself, at least. It doesn’t need to make money, but it should pay for itself. At that point it was too important for me to reestablish myself in New York, so I gave up that space.

What kinds of projects do you have coming up?

I’m working on a competition entry—I’m a finalist. It’s a huge stained glass window project for a church in Munich. There are 29 16-meter-high windows, so it’s a massive job. One of my first jobs was making stained glass windows, which really fed into what I’m doing with my new show—a lot of this is stuff I took from that stained glass windows job. For years I’ve wanted to bring these ideas back to glass, and about a year and a half ago I bought all the tools again as well as somebody’s stock of glass. I was thinking maybe I would make one little thing for somebody to see when they came for a studio visit, so that maybe one day I would get a commission to do a window. A month later, I was contacted for this competition. I have an impulse to put works outdoors, and I realized that public art projects could be a way to achieve some of that. I’ve done one or two unsuccessful competition entries, but I’m learning bit by bit. Maybe this one will come through.