One of the most important portraitists of the 20th century, Lucian Freud was the grandson of Sigmung Freud and grew up in Berlin as a Jew in the ‘20s. In 1933, he and his family fled to Britain to escape rising Nazism. There he began what would become a 60-year career marked by an often sombre and unsettling oeuvre of thickly impastoed portraits.

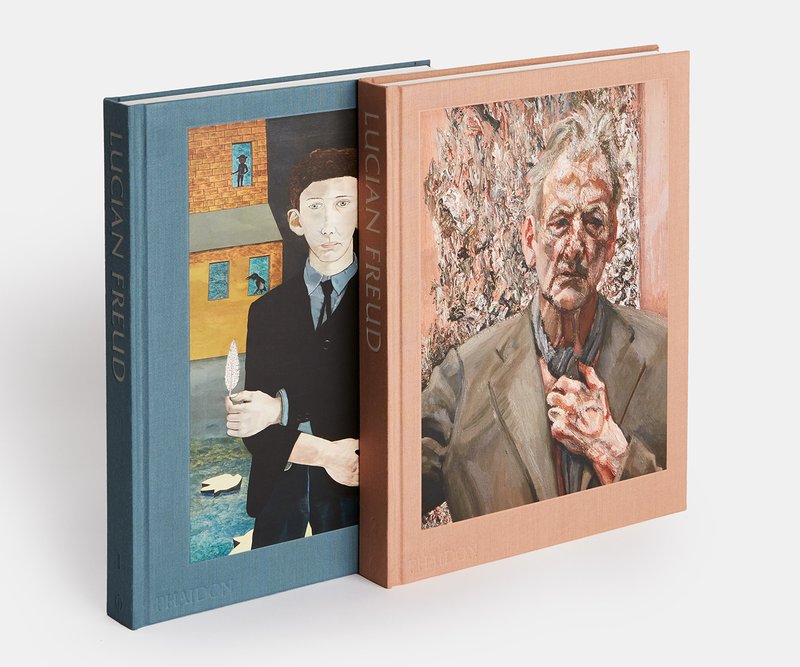

Lucian Freud was an extremely private and guarded person, and thus his paintings—depicting mostly those closest to him—are intensely intimate and penetrating. One of his most consistent models was David Dawson, who was also his friend and assistant for the last two decades of the artist's life, and who was the subject of Freud’s final and unfinished work. Now, seven years after Freud’s passing, Dawson is the director of the Lucian Freud Archive. And Phaidon’s brand new Lucian Freud , a two-volume comprehensive retrospective of the great painter, was a collaboration between Dawson and author Martin Gayford and editor Mark Holborn.

Lucian Freud

is available on Artspace for $500

Lucian Freud

is available on Artspace for $500

Here, Dawson discusses getting to know the painter quickly after their initial brief meeting; about the thrill of watching Freud's unconventional painting routines and techniques; and about the emotional intimacy of being Freud's model.

Tell us about the first time you met Lucian Freud.

It was 1990 and I had just come out of the Royal College. I was working as a part-time assistant to James Kirkman, his dealer. He brought me to Lucian’s studio at the top of a big villa in which he was living in Holland Park. We ran up the stairs and there he was at the top with these very piercing blue eyes. He had this lively aura about him and we got on immediately. From that day he phoned me every morning. I lived in nearby Notting Hill and he would phone and ask me to come round to do something or just call to get to know me a bit better.

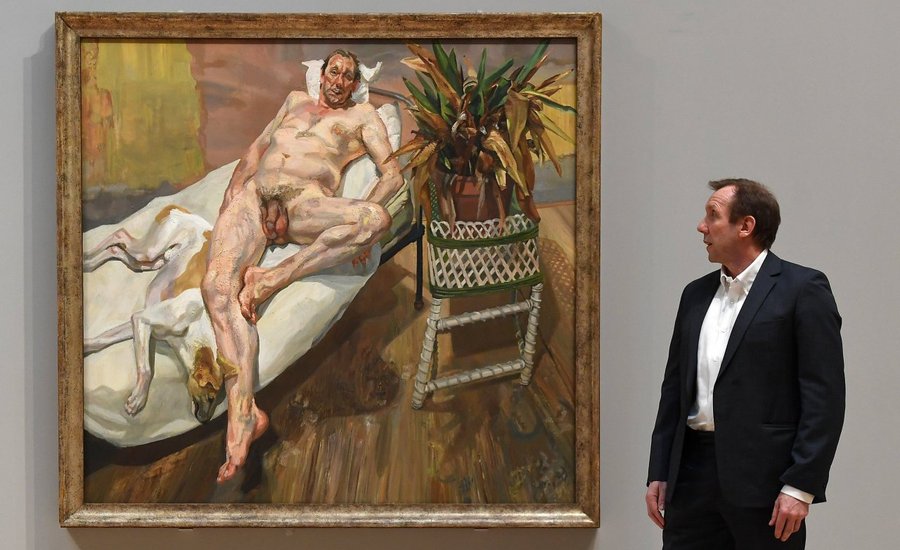

He always kept the doors closed in every room but one morning he asked me to come into his studio. And it blew me away because at the time he was doing these big portraits of Leigh Bowery, who I knew from nightclub days. These large seven-feet-tall paintings of this naked man really stopped me in my tracks. It was just the most intense thing. I thought, there’s no one better at this moment in painting than this. And I felt that I knew what he needed and how I could help him.

How did he come to paint you for the first time?

I’d been with him for about six years when he said, "I’ve got an idea for a big painting of you. I think we can start now." The brilliant thing about it being a big painting was that he had the canvas to the side, so I could look at him putting every brush mark down. And that, for me as a painter, was brilliant. He was agitated and very jumpy when he was painting. He’d jump around a bit and come right up close to you, stare at you and come back again. His levels of concentration were incredibly intense. But when he came to actually touching the canvas he was incredibly gentle. He was very light on touch. He would paint very small areas and build out. He didn’t cover the whole canvas. He would just work in a very small area, say between your eyes or your forehead or nose, and he’d bring that up almost to a level of completion and then build out. It was a very unique way of working.

What was the conversation like when he was painting?

There was a natural flow to it: incredibly intense, and then a bit of gossipy, light chat, and then we'd go back into complete silence while he painted again. If he wanted to paint you he genuinely wanted to know who you were. So he’d ask you anything and everything and this all helped in his painting, in a way. He was interested in people. He really believed in individuality. He wasn’t interested in any kind of generic overview. He utterly believed in the individuality of everything, be it inanimate or a person. That’s what he was painting—each person as an individual.

How did he choose his subjects?

Again, it was people he was very close to and wanted to spend a lot of time with. So on the whole it was often people he was having a relationship with. But he knew so many different people. That was what was remarkable as well. When he was younger he knew a lot of the great families of the UK and he would stay in their houses. At Chatsworth he painted the family there of two or three generations. He would paint his girlfriends. He was famously a great gambler so the bookies did very well because he painted the bookies to cover his debts. They’d all get paintings! In his Paddington days when he was younger he’d hang out with pretty wild locals, bank robbers and the like, and he’d paint them. He had this amazing ability of crossing all aspects of British society in the mid-twentieth century.

How long would he paint for?

The routine would be to start at seven in the morning and work through until lunch, around one. He would paint intently for twenty or thirty minutes at a time. He’d generally rest after lunch and then start on another painting at six at night and work until midnight or one in the morning. The morning paintings were always done in daylight and the night ones were always under electric light and he would never swap. Due to the practicalities of sitters he’d probably have two morning paintings on the go so the sitter for one would come for three or four mornings a week, and the other would come two or three mornings—and the same at night.

There would always be four or five paintings on the go at one time. If you were the [subject of the] main painting on the go, everything was built around you. So one painting would take prominence and that person would be the real focus in his life for eighteen months or so. And that’s what I think some sitters found a bit hard. Once the painting was finished that was it. He was gone.

Why is the book Lucian Freud so important?

There’s never been a big monograph on Lucian as complete as this. For the first time we’ve put etchings, drawings and paintings together and I’ve hopefully shown, with the editor Mark Holborn, how Lucian worked. He very often made an etching of the sitter after a painting had been completed as he felt he knew the face and person very well. And the drawings were never really preparatory drawings, they were just drawings in their own right. So the book really shows you how he worked; you can see the rhythm. It’s also amazing to see the relationships and how he gets completely caught up with one person. There are four or five pages of the same sitter. And you can definitely see the push of the last twenty years, these big paintings... boom, boom, boom, boom. When the idea for the book came to me I was very happy.

Finally, what do you think is his lasting influence on the art world?

His human feeling and his connection with an individual. I think that is what people respond to when they look at his paintings. They can relate to the empathy in his portraits. Lucian always talked about feeling when looking at a painting, about how it makes you feel. It wasn’t some abstract idea. It’s a sort of amazing combination of heart and brain. It’s about what it feels like to be human and the tenderness and openness that that can be. For me, personally, he taught me how to be a painter and how to live better.

RELATED ARTICLES: