Bursting onto the scene in the late '70s, Kenny Scharf came up with folks like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat —artists who found their place, and their people, in the basement of a Polish church on Saint Marks Place in the East Village of Manhattan. Club 57, as it was called, "began as a no-budget venue for music and film exhibitions, and quickly took pride of place in a constellation of countercultural venues in downtown New York fueled by low rents, the Reagan presidency, and the desire to experiment with new modes of art, performance, fashion, music, and exhibition."

Currently in another basement uptown is "Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983" at the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition features one of Scharf's immersive installations, filled to the brim with day-glo toys and trinkets, along with paintings and videos the artist made during that time period. Since the Club 57 era, Scharf has vehemently pursued an artistic practice that's consistently characterized as pop, surrealist, imaginative, and a bit loopy—though it spans street art, painting on canvas, video/performance, and installation.

Artspace's Loney Abrams spoke with Scharf about Club 57, about how the artist found his signature style in the dawn of the space age, and about the trouble with New York today.

The Club 57 show is up at MoMA right now, in which you’re featured pretty prominently. How does it feel to know that this place where you partied in your youth is now considered a cultural institution? Did you ever think that even the flyers that promoted the parties would end up in MoMA?

Well, I don't know. On one hand I’d say no, we would never think that. But on the other hand, I remember there were moments when I was so excited and swept away, I knew it was magical and I felt like it should be in MoMA. So there you go.

Kenny Scharf,

Cosmic Closet

(1980s/2017). Multimedia installation. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view of Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. ©2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

Kenny Scharf,

Cosmic Closet

(1980s/2017). Multimedia installation. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view of Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. ©2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

Speaking of the fliers—I noticed looking through the checklist that a lot of the ephemera in the show was borrowed from your private collection. Be honest: are you a hoarder?

Well, I am kind of because I use it later in my art. I collect garbage, plastic stuff, and I don't know when I'm going to use it but I always find a place for it eventually. So I’m a hoarder—but I use it. It’s constantly changing hoarding.

I mean, you must've had a hunch back then that this stuff would be really important eventually, because you kept it all.

I don't have a whole lot of the flyers. I do have the video tapes of the active live art and the John Sex burlesque shows and those kind of things. I knew that I needed to videotape them. I’m glad I have a little something left.

Kenny Scharf.

Carousel of Progress

(still), 1981. Video (color, sound), 14:30 min. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Kenny Scharf.

Carousel of Progress

(still), 1981. Video (color, sound), 14:30 min. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

I can imagine that when the scene first started it wasn’t fully celebrated right off the bat the way that it is now. Can you tell me how it was different than the rest of the art world at the time?

It was pretty different, I'll tell you. There was an intermingling of the nightclub and the night world with the art world, the young kids—and that was not what was going on in the established art world. The aesthetic at the time was conceptual and minimal and we were the opposite. We were just celebrating excess, I guess.

When did people start paying attention to what you guys were doing?

Long after most of the people were dead, unfortunately. But we were having so much fun when it was happening that it didn’t really matter if no one was paying attention. We were’t all banking on it or anything, we were just having fun. But we knew it was magical, that’s for sure.

What was your most memorable experience at Club 57?

If you look at all those collage calendars that Ann Magnuson made you can see that there were like 30 events a month [laughs]. So a lot of it is a blur. Of course I remember my own thing that I put on. I remember that a little more clearly just because I had to plan it as well as do it.

Can you describe what that was?

I had the first art show, which was a celebration of the space age. And back then, which was the ‘70s, you could buy space food sticks, and of course Tang, which still exists; I don’t think space food sticks exist anymore. But it was what the astronauts ate that was a liquorish-y caramel type of thing in a tube. So we had space food sticks and tang and we danced. It was very fun, I’ll tell you.

Outer-space has always been a recurring theme in your work. What drew you to space?

I think every person that lives in the sky is drawn to space. It’s the big unknown outside of what we see on our Earth place. I was born in 1958, in the dawn of the space age when the Soviet Sputnik launched. Then the whole space race was my whole life. Everything during my upbringing—the cars that were in the neighborhood, the malls and the supermarkets, the signs, googie architecture—was like super space-age and super optimistic and super plastic. So those were my first experiences visually. And there was the dream that you could get a ticket to outer-space, that by 1984 you could just get on a rocket and run around the moon for a while and jump up and down—and we really believed it. That was just too good of a thing not to latch onto.

Your paintings are so surreal and weird in a playful and delightful way. When you started painting did that style reflect the world that you were in—a surreal and playful world?

Well, I never really thought about my style—other than just doing my style. A style is something that you’re obsessed with or it's things that you want to focus on or learn as your painting and developing. I’ve always been attracted to that kind of exuberant line, going fast and forward and moving. There’s always movement. Fast cars.

Kenny Scharf,

Having Fun

(1979). Acrylic on canvas. Collection Bruno Testore Schmidt, courtesy of the artist and Honor Frase, Los Angeles.

Kenny Scharf,

Having Fun

(1979). Acrylic on canvas. Collection Bruno Testore Schmidt, courtesy of the artist and Honor Frase, Los Angeles.

In 1979 you had a series of paintings I’ve heard refered to as "The Death of Estelle." Who was Estelle?

The series you're referring to was a sequence of paintings that are in the [Club 57] show, and they tell a story from left to right. Estelle was this jet-set woman of the future. The first painting is of her just driving. And the second one is like, here’s my car!— so you get to look at her car. In the next painting Estelle is having a television pizza party, what fun! And while she’s having this television pizza party these aliens come out of the tv on top of the pizza and they give her a message about how to get a one-way ticket to outer-space. So in the next painting she’s at the airport all ready to go with her suitcase. Then the next one she’s inside the space ship and she’s looking out the window and she sees the world exploding in a nuclear explosion. And she’s pleased because she’s saying, I escaped in time, I’m pleased. So she’s fine as long as she got away. And then the very last one, which is of the rocket shoes flying in space, she’s just having fun. She’s the last soul and she’s flying around in space, and that’s it.

Dark.

[laughs] Yeah! I think so.

Were you interested in comic books growing up? This sounds like a comic strip.

No, I didn’t really read comics as a kid. I was more into cartoons on television. The only comic strips I actually would read, that I remember and collect, was Peanuts .

Right, which is what you were focusing on this past year.

Yes, I did a project with them. It was kind of cool because I probably wouldn’t have chosen Peanuts right off the bat, because I had my own characters I guess. But it was really fun using them because I already had this personal relationship with them.

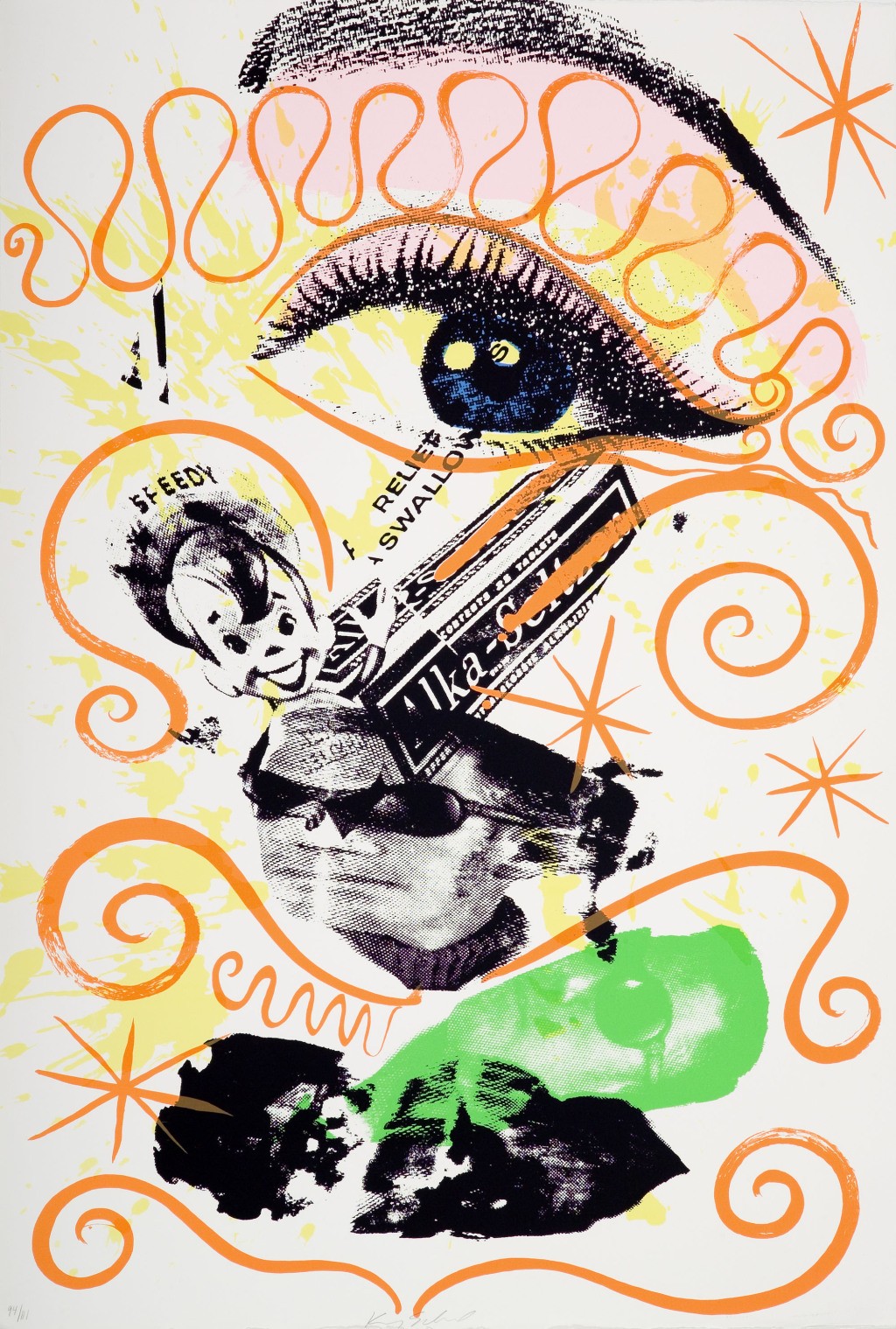

Untitled

(2011) is available on Artspace for $750 or as low as $66/month

Untitled

(2011) is available on Artspace for $750 or as low as $66/month

How do you decide whether you want to use pre-existing cartoon characters or make up your own?

I got my start back in 1981 or whenever using the Hanna Barbera characters, like The Flintstones . So I’ve been appropriating for a long time.

And then you began working with figures that were cartoon-like, but they were your own fictionalized figures and characters.

I’ve been doing that for a long time, since the future and the past collided back in 1983. That’s when they mutated and all my characters began; when they had the time splat.

Wow, okay! Why did the future and past collide in 1983?

I wrote this whole diatribe back in 1983 where I explain what happened and why my characters are now mutations of the Flintstones (the past) and The Jetsons (the future). The future and the past collided creating all time, no time, every time. And that’s chaos. That’s what it is right now, chaos.

[Laughs] Okay, got it. I guess right now is pretty chaotic, isn't it?

[Laughs] I can be! But there’s always peace inside the chaos. Don’t forget.

So your painting and painting of the '80s in general is having a comeback. Earlier this year there was the '80s painting show at the Whitney. And you can really see your generation’s influence on young emerging painters right now who are returning to the figure, to an almost surrealist representation of it. I think we could chalk this up to the fact that visual culture does have a cyclical way of recycling styles every thirty years or however long it is. But there must be something beyond that. Why do you think your style and sensibilities resonate so much right now?

To me, the art world has got so many things going on simultaneously. I’ve seen this style continue; I haven’t seen the younger artists not embracing things that I like or things that might be inspiring to other young artists. But I’m happy to know that this coming back. I’ve been doing this for so many years that I've experienced quite a few ups and downs and comebacks and returns. You know, everyone likes it better when they’re back, of course. But you just keep doing it no matter what.

Going back to Club 57... Can you picture something like Club 57 happening in New York in 2017? Or has New York just changed so much that it’s no longer even possible to have that kind of culture?

I’d say that New York would definitely be much more difficult than other places because it’s so expensive. How do you afford that kind of place? Real estate, period—who has it? An empty space that you can just play around in? And it’s just available and you can have kids through it? I mean come on.

I can't really imagine that.

Yeah, I can’t either. Club 57 was in Manhattan; it was downtown. Everyone lived within a small radius of that part of town. And now to be in New York and live affordably you’d have to be in the Bronx or somewhere far away in Brooklyn or New Jersey, and then how would you attract that kind of artist in a place that wasn't right in the center? So that’s the part that I don’t think is really possible. So maybe it would have to be in Detroit or something, I don’t know. But the problem is that there is no other city that will ever match New York in terms of what the city is all about, which is art.

Yeah. I’m an artist as well and so many of my friends are like, okay, one day we’re going to do it, we’re all going to decide which small city to move to, all together, to live affordably and support each other. But of course that will never happen. Everyone’s in New York because everyone’s in New York.

Exactly. Exactly.

And it’s hard to envision any other alternative.

There’s some of them coming out here [to Los Angeles], but it’s not the same, I’ll tell you.

Yeah, what’s your experience been like moving to LA.?

It’s great. I’m more of a daytime person now and I have grandkids I like to hangout with. I do yoga early in the morning and I go to bed early. So L.A. suites me just fine.

That sounds lovely. And not at all like New York.

RELATED ARTICLES:

6 of New York's Classic Art Bars

For the Colorful Kid's Room, With Celebrity Art Advisor Maria Brito