Artists often have a funny relationship with the art market. If not actively opposed to the commodification of artworks—as was the case with the early Conceptualists, Land artists, Fluxus, and more who made works that were deliberately unsalable—they’re at least suspicious of the market’s machinations, and rightfully so.

The rise of the flippers in the early 2010s—collectors who buy out shows of “hot” artists to quickly resell at auction for an easy profit, at least until the bubble bursts—means that young artists and their gallerists are wise to be a bit leery. Coupled with the increasing prevalence of corporate sponsorship (as with initiatives like Red Bull Studios, or the bevy of recent art-fashion crossovers), contemporary artists are increasingly put in the position of having to square their creative integrity with the promise of a paycheck.

For the Swedish artist Jonas Lund, however, these hard facts of art-world life become fertile sites for exploration and art-making, particularly of the data-driven and process-based style he prefers. Previous exhibitions have seen the artist building algorithms to generate novel (and, supposedly, optimally salable) sculptures, or paying assistants to make paintings according to a 300-page instruction manual, with the results judged by an expert panel that determines which should be formally recognized as a Lund original. In the first two parts of a trilogy shows at his Los Angeles gallerySteve Turner, Lund used point-of-sale contracts and GPS trackers to control and monitor the movement of his paintings across the globe at the hands of flippers.

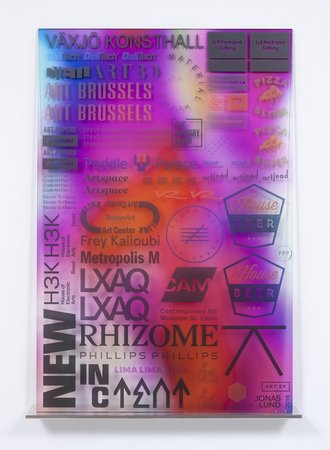

For the final installment of this series, “Your Logo Here” (on view from September 10 to October 8), he’s turned his works into the artistic equivalent of a NASCAR racer, providing ad space to various art-centric companies (including Artspace!) in exchange for exposure, supplies, and favors. (Artspace opted to post an image of the show to our Instagram account; this interview was not part of the agreement.)

Dylan Kerr caught up with Lund to learn more about the conceptual and computational roots of his singularly cheeky practice, and how his version of paint-by-numbers has led him back to a more emotive, idiosyncratic appreciation of art.

Let’s start with your new show at Steve Turner—what can we expect to see there?

It’s an installation piece, the last part of a trilogy of exhibitions with Steve Turner in L.A. The first was “Flip City” in 2014, which was a series of abstract paintings meant to capture some part of the flip market moment—there was a really intense focus on the new wave of flip collectors at the time. The show consisted of 40 paintings, all outfitted with GPS trackers on the back so I could trace their movement through the art market. The locations are continuously shared on a website that was called Flip-City.net, where you can see the whereabouts of every painting.

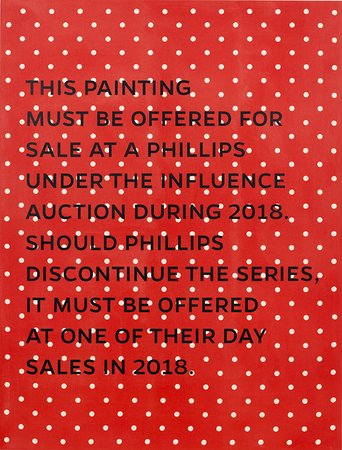

The second part of this trilogy was called “Strings Attached,” which was last year. It was also a series of paintings that have terms of sale hand-painted on top of them. Each painting has its own terms that have to be honored for the piece to be valid, such as “This painting may never be offered at auction,” or “This painting may only be purchased by a collector who agrees to purchase two more works by the artist by a certain date,” or “This painting may only be purchased by a collector who agrees to donate it to one of the following institutions.” It’s all about defining the terms of ownership and the terms of sale—to take back some control over the market and where different pieces can go, but in a more open way.

That leads us to the third show, called “Your Logo Here.” It’s the last of these three, which started during an insider market that became a downturn market where you have to be stricter about how, where, and to whom the works can move. This show takes the position that we’re in a more post-hype-market situation. Instead of making tons of painting, it’s more towards the idea of an exchange economy of bartering with companies, magazines, and institutions—all different types of actors within the art world have a kind of trade going on. For these guys to put their logo on one of the pieces in the show, I get something in return, whether that’s attention through Instagram, articles or interviews written, inclusion in a group show or a biennial, stuff like that. The logos are everywhere in this installation, which also includes a ping-pong table and a ping-pong-practicing robot in a court surrounded by banners and jerseys, plus the paintings that are an optimization of all this, together.

Installation shot of "Your Logo Here"

Installation shot of "Your Logo Here"

How have would-be sponsors responded? What are some of the bigger names you’ve been able to get onboard?

We have around 50 different sponsors right now: Whitechapel Gallery, Phillips auction house, Rhizome.org, and LXAQ—which is SFAQ, our big sponsor—while House Beer is sponsoring the event with beer. Then there’s a bunch of art fairs, such as Art Bogota, the Armory Show, Art Brussels, and the Material Art Fair.

What was the process of reaching out to these sponsors and proposing this sort of partnership like?

I just looked up their email [laughs]. It’s a negotiation in a certain way. In the beginning, you cast the net very wide because, as in all negotiations, once you have someone significant, it’s much easier to get everyone else. It was also done kind of last-minute, so we only had two weeks to get all the sponsors. It was quite intense.

What were some of the trades that you made in exchange for the ad space on your works? For instance what kind of deal did you strike with Phillips auction house? What was the best deal you got out of it, in your mind?

I’m not 100 percent sure, but I think the trade with Phillips was for them to post one picture of the show on Instagram. I traded with the Shiryaevo Biennale in Russia, so their logo on the piece could be part of the show. I think that was a pretty good deal [laughs].

That sounds like a great deal. You mentioned that this project refers to a post-art-market economy and also an exchange economy. What do you mean by these terms?

I think of this as a way of making suggestions for something else. The hype market that was happening during “Flip City” in 2014 doesn’t exist anymore, and most of these speculative collectors don’t buy art anymore because they realized that art wasn’t such a good investment, or they didn’t make enough money. It’s partly a direct comment towards that, to say, “What happens in the future when there is no support system for a market left? What can an artist do?”

By support system, do you mean traditional art-buying patrons or collectors—including flippers?

Yeah, pretty much. It’s like a part-dystopian, futuristic, imaginary situation. What happens if all the collectors don’t exist?

Are you suggesting that corporations and businesses step in to fill the gap?

No, not so much like that. I think there will always be ways of figuring out how to work within this system. This is a suggestion that there may be other ways of making deals, rather than relying on the whims of collectors to purchase your work and support your practice. There’s more back-room-trading deals going on. It’s not to suggest that the art market is gone, because it very much exists, but it’s just that it changes. It’s a little bit nuanced—I’m not offering this project as an alternative solution, it’s just another way of operating within this market.

Your Logo Here 2, 2016

Your Logo Here 2, 2016

Looking at these three projects as a whole, how serious are these suggestions for different ways to tweak the system? Is it more of a satire or critique than an earnest alternative?

I think of it as both. In order for it to be a critique of the system, I think it also has to use the system as such. For instance, “Flip City” doesn’t work if the paintings aren’t sold. I think of it more as a way of subverting or intercepting these systems with different types of observations. I imagine them as a Trojan horse—I create a piece and then inject it into this particular scene of the art market to alter it. I think the point is that it’s a bit ambiguous—it’s part satire, part critique, and part suggestion for new rules. Because it’s not up to me to—I’m not the preacher artist, saying, “This is how it is.” It’s more like a suggestion.

On a personal level, what’s your opinion on the increasing financialization of the art world?

It’s pretty complicated. Being based in Europe most of my life, where there is a pretty steady financial support for culture and art, I can clearly see the contrast to the U.S., where artists are forced to more or less rely on the market to support their practice. I think it creates different types of practices. There’s a way to value an artwork’s relevance through its market force, but I don’t think that’s always the right one. My point is that if you’re a good market artist, it doesn’t mean that your work is good or relevant, because it’s so difficult to figure out where the relevance and the quality actually exists.

My preferred system is to have a governmentally supported art world. If you as an artist don’t have to rely on the market, you can be more free to create. For example, Hans Haacke always maintained a job as a teacher in order to be autonomous from the art market. That’s the only way to confront the situation. It’s not black-and-white, though. Both methods have their pros and cons. If, very early on in your career, you are forced to deal with the market, your work is tested toward another type of relevance, another type of desire, another type of importance. So, I don’t know, man [laughs].

Installation shot of "Flip City," 2014

Installation shot of "Flip City," 2014

How successful have your market experiments proven? Have people bought in and played the game? Have the works been flipped?

Yeah, totally. I find it to be a funny side discovery—the works from “Flip City” came with terms of ownership, including a paragraph that says, “In order for this work to be auctioned, this paragraph has to be included in the catalogue text.” The paragraph gives the terms to the potential buyer, saying they have to register their ownership with me in order to replace the batteries of the GPS trackers. When people try to consign the paintings to Christie's, they wouldn’t take them because their legal team would not agree to including those terms in the catalogue. Other pieces have been consigned to Phillips auction house, although not in the proper flipping fashion. The show debuted at the height of flipping—I think that practice passed away a little bit right after that.

People subscribed to the idea of the terms in “Strings Attached” as well. Some of those works will have to reappear soon—they have to be auctioned in 2018. Others have different terms that will somehow create a situation where they will resurface.

How did you work with Steve Turner to make sure these ideas could come to fruition? These projects seem just as involved in his work as a gallerist as they are in yours as an artist.

I see it as a collaboration between me and Steve Turner. As I said with “Flip City,” if they don’t sell to flip collectors, to me it’s not a successful piece because its goal is to be sold and resold. It’s the same with “Strings Attached”—the piece only works if the gallerists are up for enforcing the potential collectors and buyers. It’s partly a game—I create the system, and he’s forced to deal with it. In certain ways, I take back control over the work, because I define the terms and who can buy them, and to whom he can sell them. It’s a little bit like I’ve reversed the role, and I need a gallery that’s willing to do that.

What are the responses from the collectors to these rule-based contracts? How do you make sure that the stipulations you set out are actually followed? Would you sue someone if they broke the terms of ownership?

For “Strings Attached” it’s easy, because most of the terms are at the point of sale. The others are something that has to happen in the future, like “This painting must be offered for sale at a Phillips auction during 2018.” If that never happens I can void the certificate of authenticity, so it’s no longer a valid piece of art. There’s a website that keeps track of all of this, so I can maintain the integrity of the project, but most of them are at the point of sale so it’s easy to verify.

Auction, 2015

Auction, 2015

Can you talk a bit of this more legalistic aspect of your work? Why work with contract law like this?

Through the contacts, I can define the rules in a specific way so I can have control over certain aspects of the works. My background is in programming, and it’s very similar to this. By writing certain scripts, I create a system that has to operate in this way, otherwise it’s not valid. It’s very similar with the contracts.

I’m not particularly concerned with going after the people who break the contract. It’s more that in defining the contract, I define the rules and the system by which everyone who participates has to play. I think that’s a very powerful idea.

Remember, we’re dealing with art. In the art world, it’s all subjective, and I think that’s the message also. Through the contract, you can somehow lower the subjectivity in a certain way, and define proper rules.

From your start as a programmer, how did you first become interested in this kind of conceptual art?

I actually started off as a photographer, and then became a programmer and made tons of net art. For me, most of the work from the last few years has all been dealing with this idea of how we trade and evaluate value within the contemporary art world. Because I’m a logically minded person, coming from that background of writing scripts that follow a certain logic, when I observe the art world and how art gets evaluated or talked about, it seems to me, from my position, that it follows no logic. Or it follows its own twisted logic.

The desire to work with these ideas comes from the desire to try and understand how it functions—if there is a system, can I figure out the system to objectively evaluate works of art? And if I can do that, can I then become super successful as a consequence? This has been my main research, but I think the more I’ve worked with it, the more I’ve learned that the whole point of works of art is that you can’t quantify this type of quality. That’s what makes art like magic. You can quantify auction value and you can quantify retail prices, but that says nothing about how you would think about the piece itself.

Installation shot of "Strings Attached," 2015

Installation shot of "Strings Attached," 2015

It’s interesting to hear you say that, based on all the work you’ve been doing with process-based art. I’m also thinking about your show “Fear of Missing Out,” where you used an algorithm to generate the titles, materials, and instructions for new, “successful” works of art. At the end of all these conceptual games, do you think it’s true that beauty is in the eye of the beholder?

I mean it is, right? It’s something like an objective truth. When there’s a new movement and there is at least recognition of hype, all of a sudden everyone is into this particular thing. People will say that it’s cynical to quantify works of art, and I’m slowly getting to that point, too. You can reach certain discoveries through this research into materiality, but I think for the betterment of the works it’s nice to say, “Yeah, okay, it’s the surprise.” How do you quantify surprise? [Laughs] I don’t know anymore. The more I find out, the more confused I become.

How did you make the shift from programming the web-based works to the perhaps anachronistic medium of painting? Why use paintings as the vehicle for these ideas and experiments?

I didn’t deliberately shift—it was more like a transition. I still make online work, and many of the other works I’ve done still have a very strong online component. I think of “Flip City,” for example, as net art, because every painting is a network. I work with tons different types of media, all on the basis of the system of what I want to address.

If you want to address the market you have to somehow make paintings, because that’s the only thing that it makes sense to make. That’s the primary vehicle for artistic expression within the market. You can sell whatever, but paintings have an almost holy status. I think the first solo show following the transition was “Fear of Missing Out,” which was also very networked. All of the materials and the creative process are very much indebted to that.

Cheerfully Hats Sander Selfish, 2013, one of the works generated for "Fear of Missing Out"

Cheerfully Hats Sander Selfish, 2013, one of the works generated for "Fear of Missing Out"

Do you see yourself moving away from this process-based work and into something a bit more expressive or sui generis?

I don’t know. Looking at all the different works, even going back to “Fear of Missing Out,” it’s all about this idea of creating a basic system. I define all the parameters, and produce the outcome as a result of the system. I think this way of working is very flexible, because I can define whatever system I deem fitting.

Is there still room for something truly different to come out of this systems- or rule-based approach—something that might get at that deeper, more affective relationship you were talking about, the unquantifiable aspect of surprise?

Yeah, for sure there’s room. Knowing how to do it is the challenge [laughs].

How do you inject the so-called magic into something as seemingly predictable as process-based art?

I don’t know. Maybe then it’s actually the materiality, or the sublime. What works for someone doesn’t work for someone else. If I knew the answer, then I don’t think I would make art anymore. It’s based in the desire to find out more, to surprise yourself, and to find solutions to problems that didn’t exist before, to subvert—something like that. For this show, much of the work won’t be visible because so much of it is in the process of getting the sponsors, writing the emails, having the conversations. The show itself is a culmination of that effort.

[related-works-module]