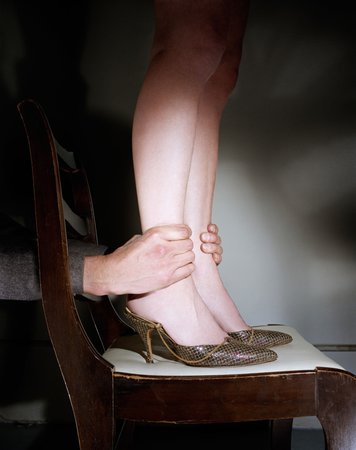

If anyone has captured on film the seductive roamings of the human mind, it’s photographer Jo Ann Callis. From a naked body trussed up in string to a rumpled head of hair tangled with beetroots, each of her surreal tableaux triggers flashes of fantasy—usually involving models with faces cropped out of the frame and with bodies garnished with domestic objects like duct tape, honey, leather belts, and red, red lipstick. There are no explanations, here. Things are about to be enacted, or just were: In one photo, two manacle-like hands clasp a woman’s high-heeled ankles. In another, a dark line traces the curved spine, neck, and parted hair of a narrow-shouldered girl lying prone, like a diagram in an old medical textbook. Both sensual and unsettling, these scenes showcase erotic imagination in its many forms, all intimate and deeply human.

Although the work may sound like a very contemporary investigation of desire, it was made some 40 years ago, predating the staged photographs of Cindy Sherman and Gregory Crewdson. Born in 1940 in Ohio, Callis has charted an unusual artistic course. By 23, she was married with two children; she later separated from her husband. It wasn’t until she was in her 30s that she took her first photo class at UCLA, with the legendary photographer Robert Heinecken.

This summer is the first time the artist has shown work from this early period, after omitting it from a 2009 Getty retrospective and the 1981 Whitney Biennial. Now on view at Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, the photographs have also been published by Aperture in a new book called Other Rooms. The longtime CalArts professor spoke to Artspace about why she kept the fetishistic project private for so many decades, the norms and ideals of sexuality, and what her influential mentor taught her about holding an egg.

Woman With Black Line, 1976–77

Woman With Black Line, 1976–77

This new body of work feels very fresh, even though it was made some 40 years ago. What’s it like for you to be showing it for the first time?

I feel less vulnerable, really. When you show recent work, you’re much more attached to it and more susceptible to criticism. If the photographs weren’t well received, I could imagine telling myself, “I’ve done so much work since then that’s different, so it’s fine.” That said, the responses I’m hearing are extremely positive. The people who have negative things to say don’t bother to tell you, thank god. [Laughs]

What about the raw and vulnerable nature of the photos themselves? I understand that you didn’t show the body of work when you were applying to teach at CalArts, which was a hotbed for conceptual art in the 1970s. Neither did you show them at your 2009 retrospective at the Getty.

Yes, there’s that. When you take a photograph, it’s recording what’s in front of the camera, according to how much light hits the film. So naturally, there’s realism. But the photos are also metaphors for feelings, alluding to inner thoughts and experiences. Psychologically, these were the tools I had and what I wanted to get at: the feelings of unease, beauty, tactility, sexuality, sensuality, and fear—fear of figuring out life, fear in life in general, fear of finding our place in it.

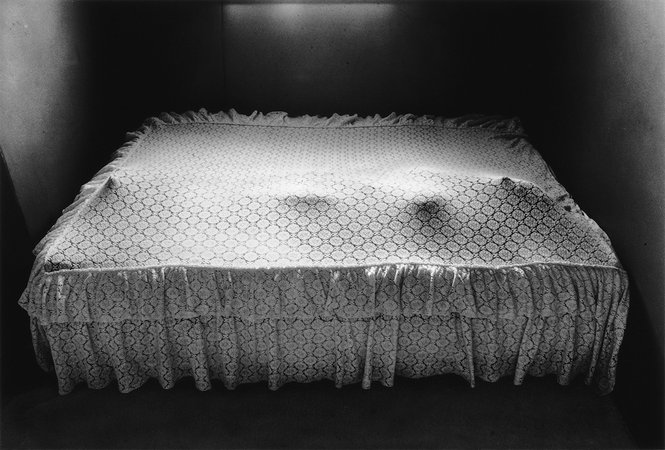

Figure Under Bedspread, 1974

Figure Under Bedspread, 1974

What inspired you to unveil this body of work today?

It was through the encouragement of two friends of mine, a couple who are collectors. They said I should show this to Rose Shoshana [founder of Santa Monica’s Rose Gallery]. Rose and her staff felt that it was very contemporary-looking, even though it had been done so many years ago, and they just loved the work.

You were a sculptor before enrolling as an undergraduate at UCLA. In your fabricated photographs, props function as expressive, tactile elements. Does your background in sculpture inform your work as a photographer?

I do think it does. Even as an undergrad in Ohio, when I was 18 and 19, I was making sculptures. I can’t say exactly what the influence is, but it’s probably in the additive process. Building plaster or clay up or putting separate elements together is about constructing something from nothing. And so starting with nothing and creating a stage—an environment, a set for the photograph—just seemed like a very natural thing to do.

Sand and Glove, 1976–77

Sand and Glove, 1976–77

At UCLA in 1973, you took a course with the legendary Robert Heinecken. Did he encourage you to explore these staged scenarios?

Yes, I remember he looked at my work and said, “You know, why don’t you keeping doing this for a while, you seem to be good at it. Don’t feel the need you have to use alternative processes”—which a lot of other people were doing at that time, using other methods of printing and photograms.

You’ve said before that Heinecken would say in class, “that’s interesting,” and with those words, you knew you were on to something. What tendencies was he encouraging, do you think?

Darned if I know! [Laughs] I don’t know! Just getting him to say it was interesting was all I needed. I would never have had the nerve to question it—it never even occurred to me that you could do that. I think it was just the praise, someone saying, “This is okay, there’s something here. Keep pursuing it and see what happens.” That was extremely powerful, especially coming from a teacher.

But it was not just his encouragement. I had just got out of a marriage and had started life as a single woman with two children. I think because I found something that I absolutely loved and was getting recognition for it, I had the courage to just pursue it.

Hands on Ankles, 1976–77

Hands on Ankles, 1976–77

In his camera-less investigations, Heinecken was transposing photos from magazines, advertisements, and pornography: compressing the commercial sphere and sexual desire. Did you learn anything from him as an artist?

There was one photograph of his that really struck me. I don’t know the name of it, but I saw it recently in his show in New York and thought, “Ah, there it is again. Yes, I know this.” In it, there’s a masked woman looking at the viewer and holding an egg between her fingers. I said to him, “I love this.” The idea behind it, he explained, was inserting an object that you wouldn’t expect to be there. If done in the right way, you can create another meaning. You hold an egg every morning when you’re fixing breakfast, but that doesn’t have anything to do with it. There’s holding an egg, and holding an egg. I remember thinking, “Oh, I get it.”

I always wanted to choose domestic objects that are familiar to all of us—they were especially familiar to me, because I was at home a lot. The domestic realm was where I lived in every way, literally and psychologically. Within those confines, there are feelings other than comfort. There are things that are disquieting, because it’s where we retreat and it’s full of all kinds of emotions. So I used everyday objects, but put them in new contexts as a way of talking about a lot of other issues.

Figure in Bath, 1976–77

Figure in Bath, 1976–77

At the 2009 Getty retrospective, you said, “I consistently want to make things that satisfy my sense of beauty.” How would you describe your sense of beauty in these surreal and mysterious tableaus?

How does one describe that? [Laughs] I remember when Lee Friedlander was making all those images outside, there was always a pole right in the middle of the frame. And I thought, “That’s a device he’s enjoying at this moment in his career.” Somebody at a lecture once asked him about it, but he never answered.

Like beauty, sex isn’t easy to put into words, or represent in visual art. As the introduction of the book points out, it has been processed by the porn industry and commoditized by advertising. In your work, however, you depict a raw, interior view of human sexuality. How did you go about approaching it as a subject?

It came from a personal place. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that the photographs are made by a woman: I’m using familiar tropes, but just from a more intimate point of view. Also, nothing is really happening in the photographs. There’s just innuendo of whatever you want to imagine. I was looking at how to get at some of those feelings of sexuality and explore them and take joy in them, making them into metaphors for fear and anxiety and pleasure.

Hair and Beets, 1967

Hair and Beets, 1967

When you were working in the 1970s, second-wave feminism was roiling across American culture, theorizing the male gaze and proposing that the personal is political. When talking about your work, however, you avoid any kind of overt feminist stance. How do issues of gender play into your thinking as an artist?

Gender plays a huge part in our lives. If you’re female, then society will treat you a certain way and you are in the world in a certain way. But I think whenever you’re dealing with sexuality, whether it’s in print or in visual arts, the issue of gender comes through in the roles people play and how you work with or against those roles, or set things on the edge. For me, it was always about vulnerability and sometimes just pure joy of and pleasure taken from looking and feeling sensations—just letting your mind wander and imagining and enjoying the ride.

These erotic scenarios appear to be moments captured just before or after an act. There are implicitly characters who are not pictured: the person who drew a pen line down the girl’s scalp and spine, for instance. Do you think of the photographs as narratives?

There is a narrative aspect. They don’t tell any specific story though, and it’s certainly not linear. They suggest something could happen, might have happened—in the mind or in reality. There are people in their poses, and they are eluding to something. Maybe they are even just daydreams.

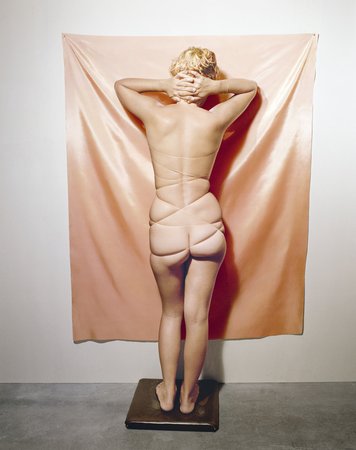

Nude Facing Wall, 1976–77

Nude Facing Wall, 1976–77

Often the photos are about power and powerlessness, domination and control. Could you talk about your own artistic control over the stage set and models when photographing.

I do like to control the image and create it and not just take what’s there. I want it to look the way I want it to look, and to evoke what I want it to evoke. I’ve never wanted to photograph outside or catch a moment or anything like that, and the models are all willing to pose and they know what that means. They’re going to follow my direction or collaborate and say, “What about this?” But mostly it’s me looking through the lens and saying, “Well, let’s do this.” I find satisfaction in being able to create something from nothing. It comes from feeling a sense of control, I think. But of course taking a picture is not like life. It’s “let’s pretend” for an hour, let’s just play and see what happens. It’s not really dominance—it’s a form of play.

Women in Crimson Slip, 1978

Women in Crimson Slip, 1978

You discovered a new emotional charge in color photography, particularly in the work of Paul Outerbridge in the '70s. As an artist, what new possibilities did color open up for you?

Because of the carbon process, the colors in Outerbridge’s photographs are sometimes not true to life. This was new to me, because photography is usually linked to the truth. You don’t purposely make skin green, for instance. I say green because I just saw an Expressionist show, and there was green flesh, and I thought, “Of course, we don’t think anything of it in a painting.” When something is set up, however, it gives the artist a lot of freedom not to be realistic. And so when I saw those colors on the skin of Outerbridge’s work, I thought, “Oh, you can do that with photographs, like painters. You can take liberties.” Photography doesn’t have to be true-to-life color.

You used color gels in the 1970s to tweak the color to get what you call “a temperature change” and to alter the light quality. Recently, you again made digital adjustments to the images. Working with this body of photographs again, did you see anything new?

By reprinting them, I could digitally emphasize colors so they were operating in the way that I wanted them to. It felt like I was working on new work, actually. I also had the opportunity to reevaluate the photographs. I didn’t see more metaphors, but it was pretty satisfying. I’ve lived a lot of life since I made them in the 1970s, but I still thought, “Yeah, they hold true.” The work is about being human, I think.