Performance and video artist Jacolby Satterwhite has made a name for himself with his immersive, idiosyncratic works, many of which involve family history and personal mythologies in fantastical animated environments that update the innovations of Surrealism and Dada. Based in New York and represented by OHWOW Gallery in Los Angeles, the artist has a special place in his heart for Icelandic avant-pop star Björk, whose first major museum retrospective is currently on view at MoMA. Here, Satterwhite describes his appreciation for the innovative role Björk has played not only in his own artistic development, which led to his inclusion in the Whitney Biennial last year, but also in the visual and sonic aesthetics of the 21st century writ large. What follows is in his own words, as edited and condensed from an interview.

Speaking as someone who’s deep into the new media genre and who nerds out on the engineers who have established the visual zeitgeist of our time, the MoMA show feels like it’s very necessary. You can’t deny that Björk created a constellation of collaborators who literally changed the way that we look at images in the 21st century. She invented a broad variety of sonic systems, whether it was the vocal album “Medúlla,” where she limits her palette, or “Vespertine,” where they recorded ice machines and spoons and other domestic utilities in order to again limit the palette and make a focused concept album about interiority and her new relationship with Matthew Barney. Her rhythms and systems and collaborations are so refined and innovative that, for me as a young person, I definitely looked to her as a source of inspiration.

This inspiration is more general than specific. Some people turn their noses up at a trend that inspires them, but I definitely don’t. That’s my truth. Like, I’m also obsessed with gaming. I could tell you about Squaresoft Entertainment and Capcom and why video game companies have heavily influenced me, or why I studied C++ when I was 14 because I wanted to go to Japan and work with Squaresoft to make Final Fantasy CG animation. You live in your bedroom and you make a laboratory of things that inspire you. That’s just normal.

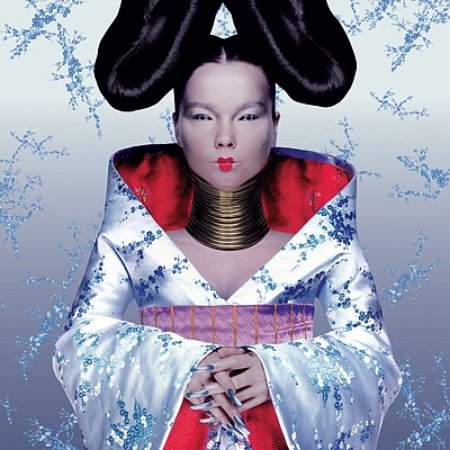

As a Millennial—and I hate that term—with your dial-up modem, you fan out on the musicians you like. As a kid in South Carolina, I would open up her album notes and look at the credits and research the hell out of the engineers and everyone else who was involved, and I developed a culture for myself through those albums. I know everything about Sophie Muller and everything about Michel Gondry, who made Björk’s “Debut” and “Post” videos. That’s how I learned about the fashion designer Hussein Chalayan, because he did the “Post” album cover jacket, or Alexander McQueen through his “Homogenic” album cover. And then you get to Björk herself. The same goes for Final Fantasy, with Madonna, for whatever else I was into. That said, Björk specifically is special to me because she just married herself to the most cutting edge. Her notion of a concept album is a little bit more refined and sophisticated than many others, and it definitely competes with some of the best visual artists who might have limited themselves to more private institutions instead of popular culture.

Björk's "Homogenic" album cover

Björk's "Homogenic" album cover

A lot of people argue that the MoMA exhibition is unfair because she already has a world stage at her disposal, but I’m sure that Jeff Koons has 2,000 times the resources of Björk and nobody had that kind of problem with his retrospective. All this criticism seems a little bit suspect. She might be able to perform at Madison Square Garden, but that doesn’t mean that she fills those stadiums. She’s never been a huge album seller, so what are they talking about?

People look at Björk so superficially. They’re like, “Oh, she just makes some cool music videos.” Yeah, the Chris Cunningham “All Is Full of Love” music video is amazing, and for that to be made in 1999 is out of control. She made some really cool, kooky videos that are gorgeous, and maybe it changed the game. People say, “Oh, it’s just design,” but it’s not, because her vision is pared down and thoughtful in a way that many artists’ are not. A lot of times we sell didactic, political things in order to wet the panties of patrons. Like, “I’m an identity artist and I’m going to give you my adversity in a really designed package so you can stroke yourself,” versus, “I’m just going to build a really abstract meta-narrative about the vocal cords, and it’s going to be really poetic, and its going to be called ‘Medúlla.’”

But beyond the visual aesthetics, I think she was also pushing sonic boundaries. If you think about incorporating sound art into the museum, there are a couple of artists like Stephen Vitiello who have been innovators in bringing that art into the commercial gallery world, but Björk has also made environmental sound art sculptures, like in “Biophilia.” I don’t know how successful those sculptures were, but the effort alone is pushing things forward.

Björk's "Post" album cover

Björk's "Post" album cover

Another example is her decision to use the producers Matmos in her “Vespertine” era, when they were known for doing residencies at Harvard for their microbeat samples of hospital mechanisms and things like that. The fact that she understood that you could use sound and language and surrealist games to form a concept album is just a little bit too radical for someone to be called a pop star, and it’s a lot more interesting than some of the people being taken seriously in the Chelsea gallery scene or the sound art world, or even Eyebeam and Harvestworks. I went to Harvestworks and I’ve worked with Eyebeam a lot—I’ve been around those communities for seven years now—and I love arguing against the pop/fine-art binary. People can be really simpleminded about how they separate the two and then stick their nose up at one.

I don’t necessarily have much to say about the actual show itself, other than that I totally get the instinct to go this route. I think exhibitions like this will continue to happen, and in 2030 some Bard student in the Center for Curatorial Studies will look back and say, “Ahh, that’s what they were thinking about then.” I do think that the exhibition could have been approached better. There are so many layers to her work that weren't explored. I’m not saying that she shouldn’t have had an exhibition. She should have. There are so many things that she did to contribute to innovating our time and helping younger people like me to build our own personal lexicons, and she certainly helped me feel confident in my own style and aesthetic as a visual artist and filmmaker and performance artist.

Björk's "Medúlla" album cover

Björk's "Medúlla" album cover

Living your eccentricity, living your system, living your rhythm, living your databanks, living with the people you collaborate with, and living with they way you choose to turn the potential of a software upside down and repurpose the process—that's the inspiration people like her give us. You can ask people like Ryan Trecartin or whoever else about this—anybody who has a voice and is really making a difference knows that it’s not just dry-ass bitches from the 1960s that are influential. I love Meredith Monk, I love Stephen Vitiello, but none of us are looking at them in order to pave the way for ourselves. Come on.

People are so in denial because of the preciousness around art. There are a lot of people who romanticize their love for fine art. I think you’re either in it or you’re not. You’re either a materiality person and you really understand the way that you focus on the materials and building an idea and building a system for yourself, or you’re a person who romanticizes fine art as a political thing with this history. They romanticize the way that Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg became the legends that they are. It’s kind of like starfucking, in a way, and so when something disrupts their notion of what Modernism is supposed to be they get really offended.

It gets really churchy, really Catholic. I’m aware of this—it’s why I’m very private, and why I play up my polarizing image the way I do. You’re going to see me be refined, but you’re also going to see me be real. I’m not going to be something for you to romanticize. That’s the problem with the Björk show, and that’s why people are snubbing it. People have a really religious attachment or way that they experience visual art, where they experience the romance behind Modernism or Postmodernism or the way they went to school and learned about certain people or certain personal mythologies. People forget that Andy Warhol invented the ideas that allowed Björk to happen. He made the pop star grid. Whenever there’s a change in something, there’s always a fight. Fine art is always supposed to have a friction, and that friction is never going to leave.