Following an explosion of new media art, photography, installation, and performance in the 1970s, painting was presumed dead. But when a healthy crop of new galleries sprung up in New York the following decade, hosting a wide range of exhibitions that collapsed boundaries between high and low art, painting swung back into the fray a reinvigorated medium. At the forefront of this renewed dedication to painting was Eric Fischl , whose depictions of American suburbia have expressed a deep reverence for the history of figurative painting and an unflinching commitment to psychologically charged subject matter, much of which was influenced by the artist’s dysfunctional childhood. “I vowed that I would never let the unspeakable also be unshowable,” the artist once said. “I would paint what could not be said.” Beneath the façade of the leisure class’ lavish lifestyles, a dark underbelly lurks—and subjects who embody this contrast between a polished surface and its relief define the artist’s oeuvre.

Like most things, painting styles and movements come and go in cycles and waves, and we’re currently seeing another rising interest in figurative painting. With this renewed interest comes a deeper look into contemporary figuration’s influences and predecessors; currently on view at the Whitney is “Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s” (where some of Fischl’s most well-known paintings are hung prominently). However, far from stuck in decades-past, Fischl is occupied by a much more recent moment in history: the latest US presidential election. His current solo exhibition, on view at Skarstedt Gallery in Chelsea until June 24, is called “Late America,” and in the following conversation between the artist and Artspace’s editor-in-chief Loney Abrams , Fischl expresses a deep concern for the state of his country and the incompetency of a certain “white, rich male.” And yet, the 69-year-old artist also voices optimism for art’s potential for “non-verbal” confrontation as well as some words of wisdom for young painters coming up today.

The title of your current show at Skarstedt is called “Late America.” What does this title mean to you?

American decline; post election.

Were all the paintings in the show made in direct response to the presidential election?

I would say they’re absolutely connected to the election cycle, which was two years long. The painting title Late America was made after the election (some of the other ones were too) and was specifically in response to the quandary that I felt in trying to figure out how Trump got elected. What just happened?

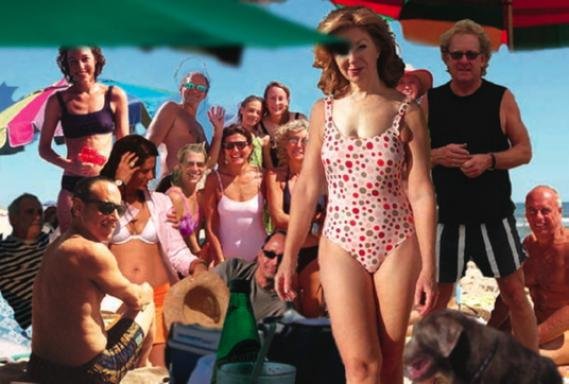

But I’ve been working on these paintings since before the election, during the election cycle. I wasn’t necessarily thinking about them as a political campaign or political statement, but just as a way to look at a world that I’m connected to and familiar with. It’s a way to sort out feelings I have about what’s going on.

All the works are images of people around a swimming pool. That kind of theatrical setting or arena speaks to leisure, to privilege, to pleasure, and to a kind of containment. I tend to think of water as this element that is archetypal and symbolic. Water is the place we came from, both as a biological species through genetic evolution, and also in terms of the birth cycle. It has a lot of subconscious resonance to it. The pool is kind of a containment of those things and perhaps a sterilization of a more wild nature.

Feeding the Turtle

(2016) © Eric Fischl. Courtesy of the artist and Skarstedt, New York.

Feeding the Turtle

(2016) © Eric Fischl. Courtesy of the artist and Skarstedt, New York.

Your series before this was the “Art Fair” series, where you took photographs at art fairs, collaged them, and then painted from the collages. It’s a subject matter that’s very “inside baseball,” very much about the art world itself. The backyard pool seems like a much more generic or universal theme; it’s representative of a typical upper-middle-class suburban lifestyle. I’m wondering how you went from something that was so specific, and for such a specific audience, back to something so broad.

If you look at my work from the beginning, it deals with where I come from very specifically. It deals with suburbia, it deals with upper-middle-class suburbia, it deals with white culture, it deals with white power culture—things like that. So, this is very much in the lexicon of my career. The “Art Fair” paintings were very much a part of my world. So, I am just painting my world. And I tend to paint until I say everything I could have said at that time. The “Art Fair” paintings came to a natural end.

Portrait of the Artist With a Battered Head

(2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Portrait of the Artist With a Battered Head

(2015). Courtesy of the artist.

You mentioned that pools speak to these ideas of privilege and leisure, but also sterilization. The same could probably be said of art fairs. But I could see how painting art fairs could easily be exhausted. You’ve returned to the pools and white suburbia after departing from them earlier in your career. So, what changed that made you feel you had more to say regarding that subject? Why return to them now?

The Trump election cycle showed a stark contrast between the potential for an America of great diversity with a reordering of the power structure, versus a dying, last-ditch effort for an old power—a white, male power—to maintain control. The contrast was so stark that it was hard to ignore, and the election confirmed not that the future would be held by the old power structure, but that it actually is over, because they elected a completely incompetent, white, rich male. This represents the end of something. I think that artists focus on their time. So, right now, my time and our time feels like it’s a moment of American decline and I’m documenting it… or an aspect of American decline, anyway.

RELATED: Co-Founder Leah Dixon On Making Beverly's Bar A Safe Space For The Art World

Do you think about your subjects in “Late America” as voters? Are these the people who decided the fate of our country?

I don’t think of them as voters at all. I think if you see the paintings there’s a deep sense of isolation; they are really quiet, in that everyone is sort of not connected with each other. To me, what is disturbing about them is that it seems like there should be a different feeling than what the feeling actually is. They are not in danger, they are not troubled, there’s nothing. They are just sitting there and standing there with the warmth of the light, the richness of the blue—yet there is this incredible disconnect. It’s profoundly tragic.

Right, these are not the perspectives we hear during an election cycle. We hear the voices of people who are passionate, people who are pushing for a certain agenda—and those are the perspectives that color and shape politics and the election process. Then there are all of these people who don’t feel empowered but instead, like you say, feel isolated and disengaged from the entire democratic process, from politics, and from their communities in general. Your subjects have this aura that is… I don’t want to say “pessimistic” because that’s maybe too specific, but they seem to have everything they need, and yet they’ve given up somehow. They radiate a feeling of malaise or despair.

What they’ve given up is higher purpose. They are self-satisfied and unfulfilled because of it.

Daddy’s Gone, Girl

(2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Daddy’s Gone, Girl

(2016). Courtesy of the artist.

This is really apparent in one of your newer paintings, Daddy’s Gone, Girl , which depicts a woman in what could be a funeral dress sitting with her feet in a pool. I’m wondering if there is any relation between the subject of that painting and the subject of an older painting also titled Daddy’s Girl , which depicts a small girl held by a man on a chaise lounge.

Absolutely. It’s revisiting Daddy’s Girl 30 years later. There are actually two paintings in the show that do that. One is Daddy’s Girl, Age 11 , which is the latest painting, the newest of the group. It’s of an 11-year-old-ish girl sitting on the edge of a chaise lounge. She’s in a two-piece bathing suit. Behind her is presumably her father, Daddy, and he’s naked, reading a magazine. Ironically, he is reading an Elle Magazine . She’s sitting there with her feet dangling over the edge of the pool and there’s a Labrador dog looking intensely into the water, as though there is something under the water that has got his hunter’s focus. He’s wearing a rescue dog collar. Anyway, Daddy’s Girl came back twice. Daddy’s Gone, Girl implies that there is an absence, perhaps a loss or a death of the Daddy, whoever he was.

RELATED: Three Figurative Sculptors Bringing the Form into the 21st Century

So, your subjects are aging with you.

I’ve tried to do that throughout my career, to try to stay within my aging. My earlier work was memory-based, so it started with a pre-pubescent, pre-teen world of mostly boys, and then began to move into adulthood, and now aging.

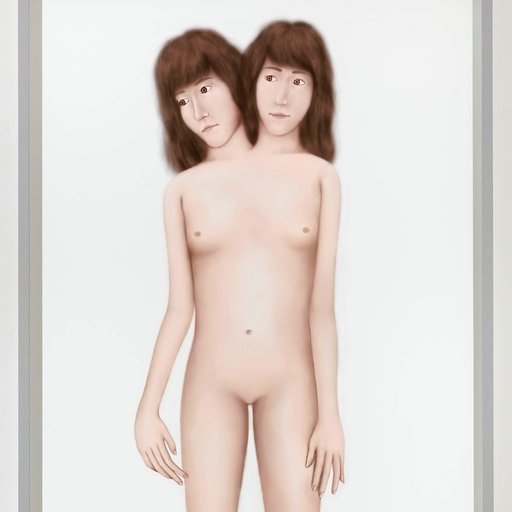

Throughout your career you’ve painted nude subjects in scenarios where their nudity is surprising. How do you decide who gets clothes who stays nude?

I always make a distinction between “nude” and “naked.” I rarely work with nude. I use “naked” because of their vulnerability. It’s irreducible and basic. It really can’t be reduced any further. It represents us at our most exposed and vulnerable. I use that as part of a trigger in the work. In earlier work, I refer to those dreams you have when you end up naked in public and that sense of embarrassment and awkwardness.

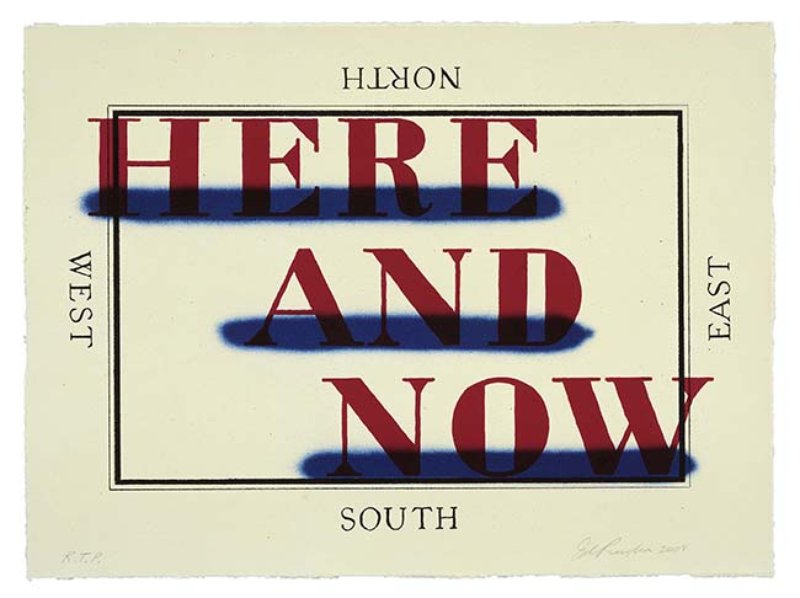

Ed Ruscha,

Here and Now

(2008). Available on Artspace for $7,500 or $660/month

Ed Ruscha,

Here and Now

(2008). Available on Artspace for $7,500 or $660/month

I’d like to talk about a project you did called “America Now and Here,” because it’s also very much about the state of the nation and about American politics. I remember reading that the project attracted interest from a lot of big-name artists who wanted to participate, but that you struggled to raise funding for the project. Why was that? Is political art a tough sell?

Well, the project wasn’t political, so I don't think that was the problem. I think that the main problem was twofold: One was that it actually coincided with the crash of our economy. People who had money were deeply concerned as they watched their wealth be cut in half. They were less philanthropic in that regard. The other thing was that at that time corporations had just lost a ton of dough and were reluctant to be seen supporting art because art represented something frivolous; they needed to stay away from that as a message. (That just shows you how misunderstood art is in terms of its cultural importance.) So, those were the two main reasons. There was another reason, which was that I probably wasn’t a good enough businessman to convince them that this was going to happen in the way I envisioned that it would. Anyway, the first attempt was a failure.

And it wasn’t political. That was the whole point of it. First of all, it was the perfect opportunity for art to play a significant roll in trying to heal a nation. This was a post-9/11 nation that had spiraled out of control and into smaller tribal pockets for protection. And there was opportunity that could come out of a tremendous sense of vulnerability and fear. We had lost our center. It seemed like what we were doing was screaming and yelling at each other. Art would have been something more palliative, more healing, in that it’s a non-verbal experience.

I asked the artists to give me something about how they felt about America, and what came out of that were some very clear themes. One was a sense of place: whether that place was as intimate as a favorite chair, or as romantic and expansive as the Grand Canyon. Then there was this idea of America as “people”—and that was viewed as either the intimacy of love relationships or family, or as generalized as your community, your postman, your preacher, etc. The third theme was America as an icon: the symbol of liberty, of opportunity, and that kind of thing. They weren’t political; they were something far more universal within our society. That made me very optimistic because I imagined someone walking into this show and also having their favorite place, their sense of people, their sense of the iconic America. This would be a sharing. I think we could use something like this again. But unfortunately, if you asked Americans how they felt about America right now, they would come back with some incredibly intense provocation for political justice or something.

Such a large part of that project too was not only asking artists to respond, but bringing these artworks to people whom we don’t necessarily consider to be art’s primary audience.

That’s the whole point. This is not about the art world. The reason I wanted it to be taken on trucks to small communities and inner cities, as opposed to hard-shell museums, was precisely to get outside the art world. It’s a way of saying that this is not about the art world, this is about ways of talking to and connecting with each other. That was the message. And that was also something that the art world didn’t understand. They didn’t understand why we didn’t want to go to another museum with the show.

Are the people in these small communities or inner cities your ideal audience? Obviously the market plays such a huge role in what any artist’s audience is, but if you were to take the market out of the equation, who would be your ideal audience?

The ideal audience is one who comes to a work of art open to the experience of it, and then changes places with the artist. The ideal audience is an audience who is open to empathy and able to receive an empathetic connection. That is as much about the ideal artist as well. It really is about connecting.

I have one last question for you, which is do you have any advice for young painters who are working today? Whether it is career-wise or working through problems in the studio. Any kind of insight?

The art world that the young artists are involved in today is not the same as the art world that I was in as a young artist. It has totally changed. My learning curve, which involved adjusting to the pressures of the art market world, had a much more solid historical base in art. Now, artists start off in this art market world, which means that the market is their base. They’re making product. When I was a young artist I wasn’t making product, I was making experience—that’s a huge difference.

My advice to young artists would be to try to learn as much about art history as they possibly can. The job of the artist is to keep art history alive and moving forward. If you don’t know anything about all of the stuff that has been done historically (and painting being the longest tradition, with the most baggage and the longest track record for invention and innovation) then you are screwed. If you want to be a great artist then you better learn about that stuff.

[related-works-module]