Every Friday afternoon last summer, it rained inside the Power Station in downtown Dallas. Gallery attendants responded, as they were instructed, by laying out aluminum pans to catch the water seeping through the concrete floor above. The tinny rhythm of the drips—musically scored by artists Tobias Madison, Emanuel Rossetti, and Stefan Tcherepnin—is just one example of the work put on by Dallas’s young alternative art space, where the programming teeters on the brink of artistic anarchy and avant-gardism.

Conceived in 2011 by skin-care-product tycoon Alden Pinnelland his wife, Janelle, the Power Station invites conceptual artists to respond to the raw and industrial context of the 1920 brick building that once housed Dallas's Power & Light company. Breaking out of the traditional white-cube gallery mold and fusty museum setting is the point here—these conventions are what Pinnell identified as confining the North Texas contemporary art scene as it was forming a decade ago.

To mark the sixth edition of the Dallas Art Fair, we spoke with the 44-year-old collector about how the city has transformed since then, its collaborative collectors, and his unruly project space where artists don’t have to please a board of trustees.

READ AN INTERVIEW WITH ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE POWER STATION

Art Advisor Rob Teeters on Investing in Young Emerging Talents

Your first show at the Power Station was in 2011 and you founded the space as a way to build up the cultural landscape in Dallas, where alternative art spaces were thin on the ground. What’s your take on the art scene there today?

Ten years or so ago, it was lacking here in north Texas. Money rained on big institutions, and I think it became a bit stodgy. But that has changed just immensely in the last five or six years, with a bunch of different things cropping up. The Nasher Sculpture Center just had its ten-year anniversary this year. And in addition to the Power Station, you have the Goss-Michael Foundation, which tends to be YBA-oriented. Some commercial galleries are doing adventurous things too, like Oliver Francis Gallery. Then, in our neighborhood, there's a place called the Drawing Room—a very small space that does very good shows. The Dallas Contemporary has also had a complete renaissance in recent years. Things are certainly happening.

Collectors have steered the art scene for some time in Texas, transforming the collection at the Dallas Museum of Art, for instance. Dallas collectors are also renowned for being especially collaborative in nature, buying a piece of art together and rotating it between collections, or pooling money to buy a work for a museum.

I’ve heard from a number of dealers that this doesn’t really happen anywhere else. And I think it’s because collectors don’t feel competitive here. For one, there aren’t as many collectors, and the bigger ones seems to each have their own area of interest without a ton of overlap. And when there is, we’ll collaborate. We’ve purchased a number of things with museums and other people. In fact, we have a wonderful Fischli & Weiss series on the wall right now called Equilibres [1984–86] that is owned by the Pinnell Collection, the Rachofsky Collection, the Collection of Deedie and Rusty Rose, the Catherine and Will Rose Collection, and the Dallas Museum of Art. The idea is that we can all enjoy it by rotating it around and hanging it at different times. And then, at some point, it will go to the Dallas Museum of Art.

That doesn’t sound like the collecting culture in New York, where you lived from 2005 to 2010. What would you say that Dallas has on New York? The Power Station might not be possible in the Big Apple simply because of the city’s spiraling real-estate prices.

Yeah, absolutely. In New York, I lived directly across the street from the Storefront for Art and Architecture and knew about all of these alternative spaces, like the Kitchen, Artists Space, and spaces in Brooklyn. Part of the inspiration for the Power Station was the sense of discovery I felt in those places—I mean just randomly walking in and finding yourself learning about something entirely new. I felt like that didn’t exist in Dallas at the time. But there is opportunity here; there is space here. It is affordable enough for people to get places as big as the Power Station. Where are you going to buy this in New York? I mean, there are probably some buildings in Brooklyn, but would it matter? There are opportunities for this kind of experience already.

You and your wife have a sizable collection of art, some 200 pieces. There are collectors around the world who display their own collections to the public, but with the Power Station, you've taken a different route.

Yeah, I think that is a pretty important distinction. I try to keep what we do privately entirely separate from what happens in the project space, because I don’t want our collection to effect decisions at the Power Station. If you're showing your own work, or you're giving shows to artists you collect, it immediately gets boring and you make decisions for all of the wrong reasons. So we have been very, very careful to separate the two.

You bought your first real painting in your 20s. What was it? And how did you transition to collecting emerging and mid-career artists?

I don’t even know the name of the first painting. It was a bad German Expressionist work of a wolf and it was really just terrible. I am glad that I don’t have images of it—I don’t even know where it is. But then a little bit later, I started buying much better things. Today, we have some important anchors in our collection, like Donald Judd, Richard Tuttle, Lucas Samaras, and Cindy Sherman. But with the way the art world has evolved, it's very difficult to put together a world-class collection of late-career artists, so we’ve started considering work also by younger emerging artists.

A lot of the art you show at the Power Station is not exactly what you’d call “collectable.” Tobias Madison, Emanuel Rossetti, and Stefan Tcherepnin famously flooded the mezzanine level of the Power Station with six inches of water. In another show, the Norwegian artist Matias Faldbakken covered the floor with bullet casings.

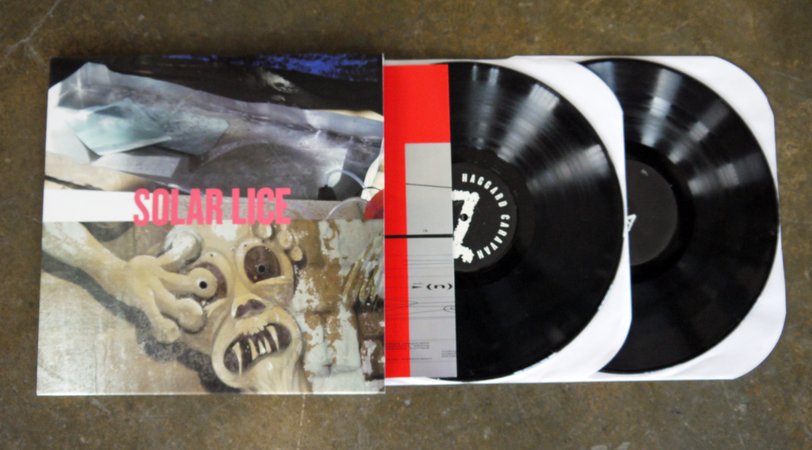

My interest is seeing that there’s a place where artists can realize completely crazy projects. At the "Drip Event" opening, we had a live band playing while water was raining down on the electrical equipment. It was crazy—totally insane—and you just couldn’t do that at other institutions. And now, instead of publishing a catalogue—with each of our projects, we make a catalogue in which the artist can do anything they want—the artists are putting out a double album. Jeanne Graff, Tobias Madison, Flavio Merlo, Emanuel Rossetti, Gregory Ruppe, William Z. Saunders, and Stefan Tcherepnin recorded a double LP at Issue Project Room in New York this month to mark the Drip Event.

Jeanne Graff, Tobias Madison, Flavio Merlo, Emanuel Rossetti, Gregory Ruppe, William Z. Saunders, and Stefan Tcherepnin recorded a double LP at Issue Project Room in New York this month to mark the Drip Event.

So, yes, we work outside the commercial context. But we did not necessarily set out to do that. The space itself is just so challenging that it lends itself to the kinds of shows that are totally different from what the artists usually do. Where else do they get to do these kinds of things? A board is never going to allow them to flood the place. But we're funded by a foundation, so the artist doesn’t have to worry about that. They can literally do whatever they want to do, within certain parameters. They don’t have to please anybody. Rob Teeters, who is our artistic director, has a huge influence on the programing, and he and I make all the decisions about projects together.

Do the local artists in Dallas figure into your programing?

This summer, we did a show called “Amarillo Entropy,” where we reached out to roughly 50 Texan artists to make artwork that we then auctioned off to support Robert Smithson’s last project, the Amarillo Ramp. After Smithson died tragically in a plane crash, Richard Serra, Nancy Holt, and Tony Shafrazi realized his last project, but it has not been taken care of in recent years. And I was blown away by the quality of that artwork by the artists here. The whole thing was conceived by Greg Ruppe, who was the conduit to these artists.

When do you know you have put on a really good show?

For me, it takes living with it to know. At some point during the three-month period when the show is up, after I've spent a lot of time in the space alone, it just kind of hits me. And frankly some of the shows that I was least confident about on opening day grew on me the most over time.

The Dallas Art Fair is this weekend. What’s up at the Power Station for visitors to see?

We were actually kind of the kick-off for the Dallas Art Fair. On Wednesday night, we opened our Fredrik Vaerslev show, which runs throughout the fair, and some 400 people were there. We served crawfish and floated two kegs an hour. It was a real party.