One of the best known and most sought-after designers of his generation, Alexis Bittar has been making and selling his own jewelry since he was a teenager—first on the streets of New York and now in a variety of high-end outlets across the globe. His innovative aesthetic and commitment to his craft shine through every one of his pieces, especially the hand-carved Lucite® bangles that have become his signature items.

In celebration of his 25th year working with the material, and in conjunction with the launch of his fall 2015 line during this month’s New York Fashion Week, Bittar has commissioned four artists (Mickalene Thomas, Cordy Ryman, Natasha Law, and Juliette Losq) to produce works in Lucite® for an auction to benefit the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center of New York.

We caught up with Bittar to talk about his work with Lucite®, his longstanding involvement with the Center, and his high hopes for young designers.

Could you tell us a bit about how this auction came to be?

It started with the fact that it’s my 25th year working with Lucite®. We decided to show our new fall collection during New York Fashion Week this year, and we wanted to have an exhibition to celebrate this 25th anniversary. The people who produce Lucite® are very excited, because there are not a lot of people who bring it into the context of fashion.

We also wanted to do something that explored sculpture and art. My Lucite® pieces are each hand-carved. I think that because they’re jewelry and smaller pieces, people automatically assume that everything is injected and molded, where in fact everything is hand-sculpted without molds. I’ve always looked at jewelry design as an art form, and I feel like it’s only in the past 10 years or so that the jewelry industry has started owning that space more and more, where people start to look at pieces as sculptural art.

Is this why you decided to bring in the artists?

Exactly. We had the idea of working with four artists with completely different sensibilities. Two reside in London, and the other two are based in Brooklyn. I liked the idea of holding on to our Brooklyn roots, because I’m Brooklyn-born and -bred. There wasn’t a set of parameters for these artists, because I really wanted to see what they would do with Lucite®. To my knowledge none of them have worked with the material before.

Sheldtrume, 2014, by Juliette Losq

Sheldtrume, 2014, by Juliette Losq

How did you decide on these four artists?

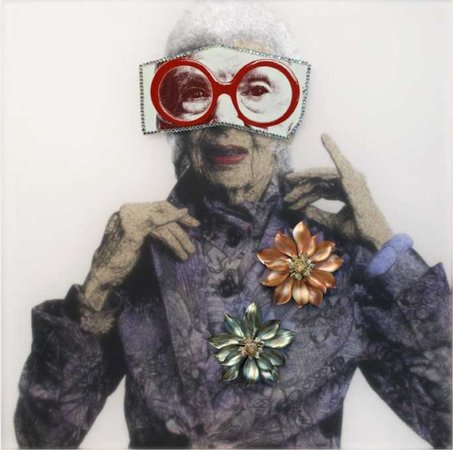

They each appealed to something unique. I’m a big fan of Mickalene Thomas on a political level, in terms of her social activism within art. She’s a vocal Brooklyn woman who is very LGBT-friendly, and she’s familiar with the Center. I respect her a lot.

Cordy Ryman and I have known each other for 20-plus years at this point. We’re workout buddies. I know his family. I basically grew up with him, and yet I never in a million years thought that we would work together. We never really talk about our work lives—it's been strictly personal. The last time I saw his work, though, I realized that we share a very similar color sensibility. I think we see color in the same way, so you’ll see a very soft, muted palette with these sharp pops of color. There’s also something very subtle about his sculptural shapes and forms in three dimensions, and I was curious to see what he would do with the Lucite®.

I knew Natasha Law more from the fashion world. Her paintings are very sexy, particularly her profiles of women, and I also respond well to her color sensibility. Her works are very much the opposite of Cordy’s—she makes big, bold shapes with strong colors.

Juliette Losq is, again, totally different. Her work is nature-inspired, but with a kind of eerie, futuristic feel. There’s something super feminine about Juliette’s work. When I look at it, I feel like I’m reading an old novel. There’s a very dreamlike quality to how she works.

In terms of logistics, we contacted each of the artists to commission the works. I also wanted to tie this into a charity—I always try to work with charities when I can—and I’ve been an active participant at the LGBT Community Center for the past 24 years. It’s a great place that builds the community, and I’ve been using it for most of my adult life—I got healthcare there as a kid, I’m on the board now, and I’m definitely a big believer in its mission.

How did you first start working with Lucite®?

I’ve sold on the street since I was eight years old, and from 13 to 18 I sold vintage clothes and jewelry on St. Mark’s Place. When I was about 21 I took a technique I learned from selling antiques—it involved hand-carving an early plastic used during the Great Depression called Bakelite—and fused it with what René Lalique had done with glass, painting on the back of crystal and gilding it. I took these two ideas and kind of stumbled upon Lucite®, a material that is typically clear. I realized I could sculpt it into any shape and manipulate the way it reflects color and light. It’s a shape-shifting material—I can make it completely opaque and matte, or glowing and high-shine, or make it look like water, or multicolored, or patterned, or carve it into a face or whatever else I want. My technique comes out of the fusion of these two ideas, Bakelite carving combined with Lalique color work.

At the time I was starting to do this, it was a counterintuitive move. It was the early ‘90s, everyone was wearing all black, and I came out with this super-bright Lucite® that was just glowing. People didn't know how to wear it. I wound up selling a little of it, but it really took 10 years for Lucite® to take off. I sold it on the corner of Green and Prince for three years before the first few stores picked it up. After maybe six or so years it started to get into places like the Guggenheim shop, but it was a very slow trajectory. People saw it as art jewelry, and art jewelry wasn't very popular then, unlike today—I think it’s having a massive explosion.

How did you decide to start making these more explicitly artistic pieces?

I love the history of jewelry. More than clothing, it has a real sentimental value and it’s passed down from generation to generation. You don’t really get your father’s sweater, but you’ll get his ring. There’s a real sense of coveting the piece.

Usually this applies to fine jewelry, but when you look at the history of fashion or art jewelry the most collectible and expensive items are from the innovators. If you look at the 1920s to 1940s, there were so many amazing jewelry designers who were using novel materials.

Of course there are tons of women who just want to wear diamond studs. But there is also the woman who is more intellectual, who wants something that exhibits her own personality and individuality. She might have all the money in the world, but she wants something that had some real thought put into it. I think this is a really exciting development. I totally understand the appeal of having $400,000 ring on your finger, but there’s something amazing about using different materials and colors and shapes to make something you can wear that looks incredible and might only be $1,000. It’s great to see art jewelry growing into more of a market, and to see so many fashion brands understanding that too.

The Guggenheim shop approached you about your work in 1992, meaning that you’ve been operating within the art world for much of your career. What is the nature of this relationship?

The museums and galleries understood what I was doing as art before anyone else, and they were the ones that pushed that through in jewelry more broadly. Before everyone started doing it, those were the stores that really understood this balance between art and jewelry. The thing that they didn’t understand was the need for it to be fashionable. That was the missing ingredient. They understood what they considered “art” in jewelry, but there needs to be an element of fashion as well in order for women to really covet it. You don't want to be walking around in an angular wire neck brace or something like that—there needs to be a certain functionality to it, and it needs to be in line with what’s happening in the ready-to-wear market.

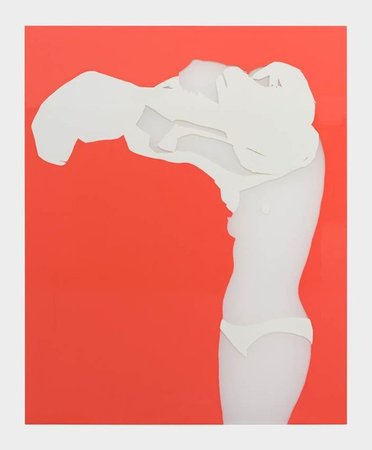

Her Head In The Clouds, 2015, by Natasha Law

Her Head In The Clouds, 2015, by Natasha Law

Are you an art enthusiast yourself? What kinds of works do you collect?

Yes! In terms of collecting I’m super old-school. I love antiques. I pretty much stop around the late ‘30s—that’s about as modern as I get. I particularly like Wiener Werkstätte, the Vienna Secession, and Art Nouveau. My favorite is Wiener Werkstätte—I was just in Vienna, and it blows my mind how forward thinking that little pocket was at the time.

How did you become involved with the LGBT Community Center?

I’ve not shy about saying that I got sober at 22, and that’s definitely one of the reasons I’ve utilized the Center. It’s an amazing organization that doesn’t situate itself as promoting one activity or initiative over another. It’s very much a house of many, and they really do it all: 12-step programs, healthcare, legal advice, assistance for elderly LGBT community members, social services, youth outreach, you name it. It was a safe place for me as a young gay man in 1990, which was not a very fun time to be gay. It was a place for me to learn how to build self-esteem.

How has your involvement with the Center changed as you’ve gotten older?

In some ways, it really hasn’t changed that much. I still go, maybe not as frequently, but I’m still there. I think that as LGBT issues have catapulted to the forefront of the national conversation and gained acceptance over the last 10 years, the Center has shifted to understand and adapt to the needs of LGBT folks without isolating or ghettoizing the community. There are still specific needs that need to be addressed—there’s a massive crystal meth problem in the community, for instance. All roads lead to the question of self-esteem and self-worth, so if that’s what drives the various issues around legal rights, healthcare, and addiction, I see the Center providing a real service just by fostering this compassionate community. I was so happy that they asked me to be on the board, in part because there aren't a lot of people there who have utilized the Center to the degree that I have. At this point I’m something of an old-timer there, even though at 46 I don’t feel that old.

Portrait of Iris with Red Glasses, 2015, by Micalene Thomas

Portrait of Iris with Red Glasses, 2015, by Micalene Thomas

What advice would you give to young designers looking to make a name for themselves?

A few years ago I would have said that I feel very bad for young designers, because it was an incredibly difficult time to build a career and a brand. It used to be that if you were online, people could knock off your stuff really easily. Your images were online, you work wasn’t selling, and bigger companies were knocking you off. This is a big problem for a lot of young designers.

I think that now the terrain has shifted, and it’s possible to succeed using online platforms. One of the benefits of sites like Etsy is that they enable people who may not have the funds for a brick-and-mortar retail presence to show their work and sell it. We’re living in an age where people are looking for something truly unique, at the same time that the retail culture is getting very good at selling mass-produced items that look like they’re a one-off. You can really build your own presence, because people want to experience something new. I recently came across this brand that I’d never even heard of, and yet they had 250,000 followers on Instagram.

As a young designer you also need to have an independent perspective. You might have a run of a business that’s based on someone else’s designs, but it won’t last long if you don’t have an independent vision of what you want to do. You really need to find your individual voice and be true to it—you can’t be swayed by what other people think. You have to hone your craft and be a master of what you do while still keeping yourself teachable.

Other than that, it’s all about working hard and being patient. We cultivate this desire to be famous and to be seen and, coupled with our desire for instant gratification, it can result in some very disappointed people. You need to be willing to do every element of a job and work your ass off. Nothing is going to land on your plate—that’s never been my experience.