At first blush, Pace Gallery’s summer group show “Blackness in Abstraction” has a relatively straightforward conceit: abstract works by an international and intergenerational selection of contemporary artists, each rendered largely in the color black. Given its lineup of some 29 A-list artists (includingRobert Rauschenberg, Lorraine O’Grady, Robert Irwin, Rashid Johnson, andWangechi Mutu), the exhibition would be interesting enough as an exercise in comparison. But in curator Adrienne Edwards’s hands, the show becomes a prime example of how an idea-driven exhibition can provide occasion for conversations that extend far beyond the gallery.

“Blackness in Abstraction” (on view at 510 West 25th Street through August 19th) takes its title and central ideas from Edwards’s 2015 Art in America article of the same name, itself an adaptation of the final chapter her doctoral dissertation at NYU’s Department of Performance Studies. (In addition to pursuing her degree, Edwards is curator and head of programming at Performa and curator-at-large at the Walker Art Museum in Minneapolis.)

At its core, the show revolves around the idea that blackness as a color, a racialized label, or a state of being is not reducible to any single quality or approach. Instead, Edwards teases out hidden historical and formal resonances between the works in a nonlinear, provisional process she refers to as “visual note-taking.” It’s no accident that the majority of works in the show are by young yet already established black artists, but it’s not the point, either—Edwards is making a far subtler gesture in favor of an expansive, “both/and” reading of the works befitting their abstract qualities.

Organizing and working with almost 30 in-demand artists is no small task, and in the days leading up to the show Edwards was, understandably, swamped. Nevertheless, she managed to find time in the days before the opening for an in-depth conversation with Artspace’s Dylan Kerr about the heady ideas animating her work, from the recently unveiled secrets of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square to the contemporary push for a more inclusive and equitable art world.

Let’s start with the basics—what is the show about?

It’s about the capaciousness of the color black, really. It’s that simple. This is a concept that I’ve been ruminating on for many years now, and it’s rooted in a chapter of my dissertation, which has a whole lot of theoretical work that is really particular to artists of African descent and why, since the late ‘90s, they have taken up this color in such a specific way in painting and sculpture. This is the chance to do what I call, in this physical manifestation of the show, visual note-taking.

What does that phrase mean to you?

It just means that it’s unresolved. I won’t really know what that show is until I go in there next Thursday and it’s all up. I like that openness, that sense of experimentation with objects. It’s something I’m accustomed to doing in relation to curating live performance. For this visual-art exhibition, I wanted to retain that energy, that sense of possibility in the show. That’s really what it means to me.

The show is so subjective. A different curator would do an entirely different survey with this topic. It’s like that song—“these are a few of my favorite things.” It’s literally that. I have an obsession with artists like Irwin and LeWitt and [Ad] Reinhardt, and I see the ways in which their work is such an influence on artists like Adam [Pendleton] and Glenn [Ligon] and Oscar [Murillo] and Ellen [Gallagher], and, well, why not put them in conversation? I read in a catalogue essay that Ellen Gallagher’s grid is deeply influenced by Sol LeWitt. Well, let’s put Ellen in a room with Sol. Let’s see what happens.

Sol LeWitt's Wall Structure Black, 1962. Photograph by Ellen Page Wilson © 2016 The LeWitt Estate /Artist Rights Society(ARS), New York

Sol LeWitt's Wall Structure Black, 1962. Photograph by Ellen Page Wilson © 2016 The LeWitt Estate /Artist Rights Society(ARS), New York

Was that part of the impetus behind this decision to put this amazing lineup of younger artists with these giants of 20th-century art history?

Yeah—that’s the way I think about their work. They’re somehow deeply in relation to each other.

Can you say a little more? What are the connections between these works beyond the obvious—beyond the fact that these are largely abstract works and largely in the color black? What are the deeper connections you’re interested in drawing out?

With these works, there’s an idea that a work of art is not only made in the context of the world, but that this work of art is made of the world, meaning the work of art does not stand alone.

This is my only battle with Reinhardt, because he insisted on this impersonal, isolated, very insular, actually a kind of even intra-medium conversation, a conversation just among painters. He was so about that. It’s something that I would challenge in his work if he were here to talk about that.

The capacity of the object on its own terms became a connective tissue among these artists—it was very consistent between everyone in the show. You have Irwin writing on conditional art, which is essentially just two words to describe what I just said about art being of the world. Louise Nevelson is an original affect theorist, in a way. Her obsession with the color black was in part due to it having such a profound theatricality, such an ability to summon something from you. Well, that’s what Minimalism is all about. I was interested in this material shift in relation to the object to accommodate more complex concepts.

Here you have a seemingly pristine work by Reinhardt that’s actually already muddied with reds and blues and greens in order to get different shades of black. You have that shift to the thickening of the material of black matter in Ellen’s hands, or Glenn’s hands, or Adam’s hands. I was really interested in how the material began to radically shift to reflect that complexity.

Consistent among all these artists is an effort to use that sense of openness to speak to things that are really complicated in the social, political, and economic contexts. You have Koji Enokura coming out of Mono-ha, the failed student movement in Japan, and turning to nature. Beyond the color that you find in nature, there’s black. There’s also performance in relation to that. We can even turn to Reinhardt’s cartoons and think about how deeply socially oriented and political they are. There’s something bubbling around these artists that understood that abstraction and minimalism have power, an animating force.

How do abstract works speak to some kind of social message or political power?

I’d like to think about it as a kind of radical openness, and I think that happens on the subtlest of levels.

When you’re in front of a black monochromatic work like Reinhardt’s or Irwin’s, for example, or even Rashid’s black mirrors, there’s such a withholding of information that it actually begins to do the opposite—it actually begins to elicit something from you. It’s demanding something of you. I’d like to think of these works as screens or scenes of projection. It’s not merely about what that work is meant to do there—whatever the artist’s intention is—but rather about how that vibration changes what you bring to it. Whatever resonance it has occurs on such a fundamentally personal level, and that’s the force of these works. It’s vibrational. It’s the only way that I can really put it.

Ellen Gallagher's Negroes Battling in a Cave, 2016. © Ellen Gallagher. Photography by Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Ellen Gallagher's Negroes Battling in a Cave, 2016. © Ellen Gallagher. Photography by Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Was there anything you found in the process of organizing the show that you weren’t expecting?

One was this question around the relation of printed matter to abstraction, which you can trace in multiple pieces here—I was actually surprised at how prevalent that became in the show. It was unexpected in part because a number of objects—over a third of the work—were created in response to the show. I was just like, “I’d like for you to be in my show,” and the conversations would shift to, “I’m going to make something.” Printed matter was this thing that just kept coming up.

It really hit me in a conversation with Ellen Gallagher around the fact that this connection has always been there in relation to the black monochrome. They recently discovered that Malevich’s Black Square has that cubist composition underneath it, as well as a racist joke. [See here for the full story.]

What a timely connection—that news only broke this past year.

I was invited to do this show January of 2015, and this all came out in November. I was already totally underway with the show, and Huey Copeland sends me an email with the article and all these exclamation points. I wrote back, “What a gift.” There’s that black square on white ground, and what’s hidden insists upon being known. I think that’s a beautiful metaphor at play.

It was so instinctive on so many levels. I’ve always been thinking about these artists and about blackness in relation to Modernism and particular abstract forms. There’s a kind of unspoken, unspeakable history that’s always looming whenever we talk about Dada or Surrealism or Cubism—blackness has always been there. Whether it’s a reference to African sculpture or art in Cubism or a desire among Dadaists to unravel language and nonsense—look at where they turn. As deeply problematic and embedded in racist ideologies as it is, that’s where they turn.

It’s a sort of wink and nod when I say blackness has always had seemingly unlimited usefulness—I mean that in a multitude of ways. It’s no accident that at the time that all this is happening within these art movements, we also have a massive colonization happening. There are ways in which this effort was also fueling the capitalist structure. These things are all bound together—that’s the world that these artworks are made of.

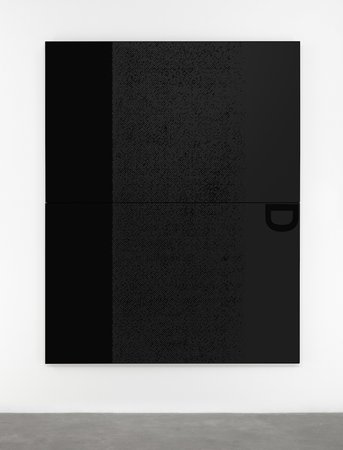

Adam Pendleton's Black Dada/Column (D), 2015. © Adam Pendleton. Courtesy Pace Gallery

Adam Pendleton's Black Dada/Column (D), 2015. © Adam Pendleton. Courtesy Pace Gallery

Prior to this show, you were primarily curating performance pieces.What is it like transitioning from that realm to working with not just a few visual artists but 29 artists of this stature? How did you wrangle these people into such a tightly conceived show?

It’s been so much fun. I feel like I’m the luckiest person in the world, honestly, to be able to do this work.

You are working with some really amazing people.

And I’m very lucky that they agreed to do it. I’ve worked with many of these people before. That dialogue is very important to me—curatorially, it’s the way I like to work.

The thing about the performance aspect of it, though, is that my interest in performance is not only about live work. It’s very much about performance as a lens of analysis. That’s the way that I approach everything. The reason why I keep a lot of openness around this show and resist specifying what I think it is—why I refer to it as “provisional” or “visual note-taking”—is because when everyone shows up and sees the show, I’m going to standing there right with them going, “Huh, what is it doing?” I’m seeking that encounter too. I try to look at objects in relation to how they perform or what they do in the world. Of course, I could have easily done a show without new or site-specific works. I didn’t because I’m not necessarily used to working that way.

It seems like the show is about developing something from these conversations rather than just reorienting objects in the space.

Totally, totally, and that has been extraordinary. I think about an artist like Jonathas de Andrade, a very good friend and an artist I’ve worked with before. We’ve been having these conversations for years now, and I remember that he went to do some research related to a new project that he was thinking about working on [based around Brazil’s Rural Landless Worker’s Movement]. He sent me 430 photographs to look at, and when I saw them I went, “Oh my God—you’re kidding me!”

I call him in Recife immediately and said, “Listen, there’s black squares everywhere. Am I making this up? Am I seeing things? Do you see them?” And he was like, “Oh, shit, you’re right.” He wasn’t even thinking about it—I had my eye attuned to it somehow. I had this goosebumps moment, because of the relationship of his work to my project. If you think about capitalism, if something is functioning financially we say it’s “in the black.”

This idea just has so many tendrils—it extends into everything.

It’s endless. The fact that these Brazilian revolutionaries were occupying land, that the materials most available to them are sticks and black tarp, and that they should build the base of their movements out of these materials—that’s just beyond poetry to me. It forces us to think about these black squares in radically different ways.

Louise Nevelson's City-Reflection, 1972. Photograph by Al Mozell © 2016 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Louise Nevelson's City-Reflection, 1972. Photograph by Al Mozell © 2016 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

These artists are from such diverse backgrounds and contexts—how do they stand in relation to one another in this show?

One of the things that I hope comes through is a kind of openness to looking at all of these different artists on the same plane and really forcing people to think about why they’re placed together. I’m interested in how a Rauschenberg can be a footnote to Glenn Ligon, as opposed to Glenn Ligon being a footnote to Rauschenberg, or how LeWitt becomes a footnote to Adam’s "Black Dada" project.

This stance seems to dovetail nicely with the ideas around the so-called atemporal moment that’s happening right now, where lines between past and present are getting blurred or otherwise ignored in favor of a kind of radical contemporarily.

This is why I have to masquerade as an art historian as opposed to actually being one, even though I do have a Masters in art history. It’s because I don’t believe in things like “post-.” You’ll never hear me say things like, “This person’s a post-conceptualist,” because I don’t think that—things are accumulated, they’re anachronistic. No one comes and draws a line between movements. These things bleed and reverberate all over each other. That’s the way my mind is wired, so that’s the way the show is structured.

In your 2015 Art in America article in which you laid the groundwork for this exhibition, you write about the multiplicity of blackness that the concept is far more than the “singular, historical narrative or monolithic subjectivity” and go on to say that, “In response to the demands placed on black artists for social content in their art, I put forward blackness in abstraction.” What do you see as the relationship between “black” as a racial category that we use in everyday speech and the “blackness” that you’re talking about here, which is a much bigger concept?

Blackness in itself is like black holes in the universe. There’s a reason that that’s the basis of our physical reality. It is this seemingly singular thing that is endlessly manifested. It’s unwieldy, and it’s untenable because it’s so unwieldy. You can’t contain it.

The fact that abstraction was tied very early on to the task of articulating, politicizing, and then legislating black humanity points to the real political projects that needed to happen. The notion that you could be ⅗ of a person, as was the case in this country—that itself is a profound abstraction. I’ve always thought about blackness as this thing that is the most abstract construct in our social system. That’s what I perceived the artists in this show were responding to.

I would probably think of many of these people as conceptualists. It’s not in the sense that Lucy Lippard articulates, which is the sense of dematerializing the art object itself. I would suggest that the dematerialization exists elsewhere, and that in order to make up for the dematerialization that concepts of race, gender, sexuality, or whatever engender, you have to in fact materialize the object.

Glenn Ligon's Death of Tom, 2008. Photograph by Brian Forrest Installation view at Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Glenn Ligon

Glenn Ligon's Death of Tom, 2008. Photograph by Brian Forrest Installation view at Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Glenn Ligon

There are clearly some very serious structural issues around the representation, or lack thereof, of black artists at all levels of the art world. This is a show featuring well-known artists that are largely—but not entirely—cool, young, and black, and the fact that that’s an aspect of the show unusual enough to remark upon should give us pause. How do you think this exhibition fits into the goal of having a more equitable art world?

I don’t know. Everybody’s got a thing, and my thing is doing work like this. Somebody else might have a different imperative. Part of it is a lack of understanding, I think, of how things work—there’s a naiveté among many people about how the art world really functions.

How so?

It’s a system itself, and it’s hard to understand how one get access to it. I don’t know how many times I’ve talked to artists about how to get gallery representation, or how to get the support they need to fabricate a work. There’s a real economics to being able to do this work. That’s why I say it’s such a deep privilege to do this.

It’s also an ecology, so all things feed on themselves. I’ve never had the opportunity to not know a broad swath of art history, western or otherwise—meaning that I could not function as a scholar or a curator if I didn’t know who Reinhardt was. But you can do that and not know who Sam Gilliam or Frank Bowling are. Until everyone feels the kind of imperative to fully understand this side of art history, then we’re always going to have some problems.

All of this is a question about values. Why isn’t so-and-so being shown? Or why aren’t more people being shown? Or what kind of shows are there? Or why isn’t the writing as subtle and complex as oftentimes the works of art are? It’s a matter of value. Do I value this work enough to sit here and really come to terms with it, to struggle with it?

We haven’t figured things out, but I think it’s a lot better than it was when I started. Even in terms of curators, the work that I do would not have been possible if it hadn’t been for people like Thelma Golden, Kellie Jones, Lowery Stokes Sims, Valerie Cassel Oliver. When I first started, those were the only people. That’s it. We’re talking in the world. On the planet. Now there’s maybe 10 of us doing the work curatorially, and Thelma’s done great work to convene us and keep us talking with one another.

I wanted this show to have some surprises, but I also wanted it to have a feeling of being among peers, in the way that Rauschenberg and Reinhardt were peers. An artist like Glenn Ligon is a peer of Rauschenberg now—I want that. I wanted to work with people who I see as being, if not yet fully established, solidly on good ground to be there. That was very important to me. I think a different conversation can be had.