If you're like me, a large portion of your Instagram feed consists of emerging art, and partially nude women artists taking flash photographs of themselves holding a copy of the book I Love Dick , accompanied by wildly self-aware, intellegent captions about performing femininity and subverting the male gaze. Maybe you're wondering, what is this Dick that everyone's so infatuated with? And if by chance you haven't seen anyone gallivanting around with this book, its title blaring like a scarlet letter in the arms of a woman who likely just sauntered off of a fashion show runway directly into a seminar, I am informing you now that a lot of people are reading this book.

Author Chris Kraus , unofficially deemed the 'art world's favorite writer,' is the author of numerous titles including I Love Dick, Aliens and Anorexia, Torpor, Summer of Hate, Where Art Belongs , and most recently After Kathy Acker , a biography of the late, notorious writer. Of the newest release, author June Phillips writes “hardly anyone writes better or more insightfully than Chris Kraus about the lives of women and artists.” Kraus herself is a woman and artist, though her written frustrations with lacking traction as a filmmaker became better known than the films themselves. (Kraus's most recent film, "Gravity and Grace" (1996), is an 88-minute unconventional narrative following two college girls-turned-prostitutes who end up falling into a doomsday cult.) Kraus is masterful at blurring the lines between autobiography, philosophy, art criticism, and experimental fiction. She's been a central figure in the art scene since the ‘80s, but only recently has her work been deemed worthy of critical review and mainstream attention.

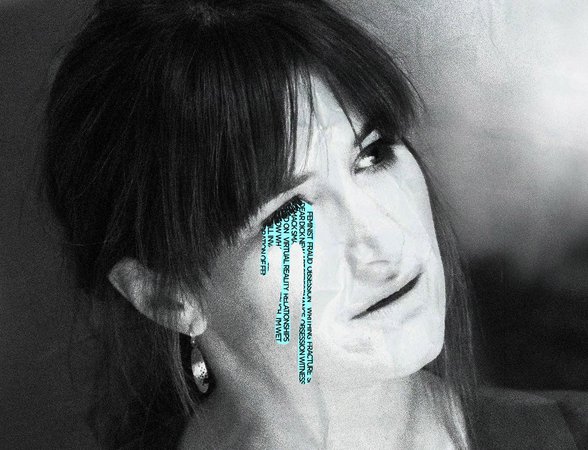

Chris Kraus, from the 2006 edition of 'I Love Dick' published by Semiotext(e), Image by Daniel Marlos

Chris Kraus, from the 2006 edition of 'I Love Dick' published by Semiotext(e), Image by Daniel Marlos

When it was published in 1997, I Love Dick didn't sell (I know, it's hard to imagine a book with such an enticing title not selling). Instead, it was disregarded as gossipy and self-indulgent. Artforum called it “a book not so much written as secreted,” (and not in a good way). In 2006, the book was reissued with a foreword from effortlessly sexy-cool poet Eileen Myles by Semiotext(e) , the independent press that Kraus co-edits with her ex-husband, critic/theorist Sylvere Lotringer and writer Hedi El Kholti . This time around, the book was adored by academics, and became an instant classic in certain circles. Myles writes that “when I Love Dick came into existence, a new kind of female life did too.” In 2011, New York Times writer Holland Cotter referred to Kraus as “one of our smartest and original writers on contemporary art and culture.” But the book still definitely wasn't a facet of the mainstream.

So what made this book sky-rocket from a "gossipy" flop to a 21st century classic? (Amazon recently adopted the story for a mini-series; in 2017, what's a greater achievement?) Why are all of these intelligent, strong women everywhere suddenly raving about a book called I Love Dick , a whopper of a title that is seemingly the furthest thing from a feminist sentiment? And why are all of these cis-heterosexual men pretending they've read the book, coming up to me while I'm reading on the subway and saying "Chris Kraus, I love his work" (or “good to know what you like!”, as writes Leslie Jamison for the The New Yorker )?

What makes Kraus's writing so rousing is her conflation of privacy and performance; and fiction and reality. Her work is about her, and yet it’s about something much greater. Her honesty is jarring. In an interview with Martin Rumsby , Chris says that at the time of writing I Love Dick , "(she) didn't know (she) was writing a book." She simply began writing letters to express her feelings of infatuation, and what started as a declaration of love became a vomitous, gushing flow of repressed thought. (So Artforum wasn't exactly far off).

On the surface, I Love Dick is about a failed-filmmaker named Chris, who is (surprise!) based on the author herself, and her long-term husband, Sylvère , based on her real-life ex-husband, theorist Sylvère Lotringer. Chris develops the hots for a man named Dick, based on Dick Hebdige , the British media theorist and sociologist, (apparently much to his chagrin), when the three have dinner one night. Her sex life with Sylvère has dwindled, and she suddenly feels a resurgence of desire for this aptly-named academic. She imagines him as a perfect, god-like being, and craves recognition from him. So, she begins writing him letters: "I thought that if I could just articulate clearly enough... he would fall in love with me," says Kraus. But her desire builds and she finds that she can't stop writing; it has become a compulsive act. Sylvère gets involved and the two partake in this "game" of writing letters. And that's just the beginning.

I Love Dick is a manifesto of sorts for those who are told that they overthink everything; that they are obsessive; that they have too many feelings. Author Michelle Tea writes “if America were to fling up a chain of roadside motels to be used as a needed refuge for girls too smart for their own good, the writings of Chris Kraus would be the bitterly comforting Gideon Bibles tucked into the bedside.” You start out on page one vulnerable; experience the madness of desire until it evolves from painful and confusing to performative and cathartic; and you come out at the end self-assured, realizing that your desire for expression was never about the tangible object of your desire. "Dick" is merely a vessel of self-discovery. The book operates more like an extensive monologue than a work of fiction, likely informed by Kraus's film and playwriting background. Chris invites you to witness her ecstatic, hysteric performance firsthand, one in which she plays all of the parts. "You don't want to just write a story, you want to act it out," says Kraus.

---

I showed up early to Kraus’s reading of After Kathy Acker at CUNY back in September, as I’d heard from a friend that it would likely be filled to capacity. An hour and a half before the reading was set to start, I sat in an auditorium amidst a sea of femmes, mostly in their 20s or 30s, each hunched over and scribbling in their notebooks. The girl next to me, wearing a long braid, red kitten heels, and a low-backed silk dress the same color as her skin introduced herself to me and we started chatting. “Have you read... the book?” she asked, pulling a copy of I Love Dick out of her leather purse. I nodded, wondering whether she knew that the reading was for the release of After Kathy Acker . She said she was an artist, smiled, and then visibly embarrassed, turned away and began writing voraciously in her notebook. It became apparent to me that this audience consisted largely of people who saw themselves in Chris. Women artists who never thought they had anything good enough to say; who never thought anyone would want to listen to them; who hid behind their sexuality because it was easier than calling yourself an “artist.” That’s the I Love Dick phenomenon: the emergence of the female artist.

So why is this book just getting the recognition it deserves now ? Well, aside from the fact that women artists are finally being recognized and celebrated for their work more than ever before, the true feat of the book is its pervasiveness in mainstream culture. If you think about it in the context of the digital age, its relevance makes sense. In a time where so many of our social interactions are virtual, Kraus's narrative seems to be all the more potent. We long for closeness; interact obsessively through social media; construct images of ourselves based on our virtual interactions and our presentation to others; and without realizing it, lose sight of what is real and what isn't, plunging deeper into loneliness. I Love Dick is a document that chronicles the madness of virtual relationships, despite its being written long before the iPhone ever existed. While Kraus employs the positively archaic form of letter-writing (gasp!) in her work, the book represents 21st century relationships arguably more aptly than any contemporary texts.

---

So we have to talk about this Amazon Prime mini-series. In May of 2017, I Love Dick was adapted by Eileen Myles 's former partner, Jill Soloway, and Sarah Gubbins . It stars actors Kathryn Hahn ( Transparent ), as Chris; Griffin Dunn ( Dallas Buyers Club ) as Sylvère , Chris’s husband, “Holocaust scholar,” and resident at what appears to be the Chinati Foundation , where the series is set; and Kevin Bacon ( Footloose ) as Dick, the tight-Levi's- and cowboy-boot-wearing, phallic-sculpture-making artist ( a la Donald Judd ). IMDb summarizes the series as the story of "a married couple (whose) relationship is put to the test when both the husband and wife fall for the same male professor." I watched the series tepidly at first, intrigued but also wondering How on earth could they make this book, which takes place so much in this writer's head, into a television show ?

Kathryn Hahn as Chris Kraus in 'I Love Dick,' image from Amazon Prime

Kathryn Hahn as Chris Kraus in 'I Love Dick,' image from Amazon Prime

Let’s just say that if you were trying to cram for your reading assignment by ‘just watching the movie’, you’d likely fail. The series and the book are wildly dissimilar save for the basic plot line. The book consists of musings on the works of female writers, artists, and filmmakers, while the show distills these works to fleeting transition shots between scenes of a slapstick rom-com. Soloway adapts Kraus's philosophical rant into a tragically conventional story about a sexless marriage between two academics whose desire is reawakened when a cowboy art-god enters their lives. Before watching the show, I’d never considered Dick as a person as much as he was a concept or entity. So seeing Kevin Bacon in cowboy boots with his jeans slung low on his waist, cradling a baby sheep; while entertaining and admittedly enticing; was far removed from my experience of reading Kraus’s work. But that’s not to say that the show isn’t entertaining.

Hahn, Dunn, and Bacon expertly play caricatures of each role: Chris sort of just flops around, making a fool of herself and contorting her face a lot; Sylvère is a smug, traditionalist academic; and Dick is well, a gigantic Dick who says things like, “I’m post-idea” ( gag ). But the most compelling aspects of the show; aside from the beauty of Marfa, Texas itself (if it doesn't make you want to finally move out of the city, I don't know what will); are performances from artist India Salvor Menuez and budding actress Roberta Colindrez .

Menuez plays Toby, a young Guggenheim fellow whose work "reduces hardcore pornography to its shapes." She postures herself a threat to the patriarchal, phallocentric art world in which Dick is revered as a deity. At one point she literally breaks his "perfect" phallic brick sculpture while dancing around in his gallery. (Menuez's real-life persona adds some street cred to the production; they're somewhat famous among New York's cool-kid art crew). Devon, played by Colindrez, is a Mexican-American Marfa-native playwright who has aspired to embody Dick's masculinity since a young age (her family worked on his ranch). The two develop a steamy relationship that is intoxicating to watch.

What distinguishes the show from the book is that it opens it up; it contextualizes the narrative; it queerifies it. It seeks to open up a conversation about intersectional feminism with regards to gender, class, and race. Whether it does this successfully is debatable (there are a few lines thrown in randomly in which characters question their privilege to pursue being an artist/academic vs. the suppression of the working class—but that's about it). But it does shake up Kraus's original narrative's posturing of gender roles in a predominantly heterosexual context. In an article for Paste Magazine , Menuez writes, "I hear lots of people talking about the female gaze on I Love Dick . I see a queer gaze. Maybe they’re not mutually exclusive, but, to me, the distinction feels important. There is no linearity to these characters' sexuality. We see that when we peel back the shame, in the episode 'A Short History of Weird Girls.'"

The episode she refers to appears as a manifesto: with screen-filling bold white words on a stark red background. It consists of monologues from curator Paula ( Lily Mojekwu ), describing her deep reverence for Dick's work and her desire to get him to acknowledge and feature the work of female artists in his gallery; Devon, explaining her desire to be like Dick and discover who she is; and Toby, chronicling her desire to supercede Dick; interwoven with records of their internalized inferiority complex. Honestly, if you only watch one episode, this is the one to watch. It captures the frustration of women in the art world, and gives them a platform from which to speak. However, the show simultaneously asserts that women are art without needing to create or do anything except exist; which isn't exactly liberating. (In one scene, Toby (Menuez) takes off her clothes and live streams herself reclining nude in the desert like an odalisque figure, surrounded by trailers of working class, "mostly brown dudes." She says it’s "an exercise in the mutual debasement of foreign bodies invading foreign lands.” Apart from being, as Devon asserts, essentially "unethical(ly)... using these guys without their consent," it also simply serves to perpetuate the fallacy that women are just incapable of making good art, lest it rely solely on their natural beauty.)

The show certainly has its flaws: it's highly glamorized, can be preachy at times, and often feels like a performative reading of signs at a women's rally; but what is compelling about it is the way that it puts its viewers in a vulnerable, uncomfortable place themselves. It makes us question what we think we know and desire, and ruptures traditional modes of thought. While it dilutes the original work, it also makes it more accessible. If making art is about responding to, subverting, and altering that which comes before it, then this show has captured the art world of 2017: Sometimes it's a circle jerk, and sometimes it's revelatory.