Although it may seem strange to devote a year-end roundup to the subject of atemporality, 2015 found the art world in a state of chronological confusion.

The year began, so to speak, in December of 2014 when the Museum of Modern Art opened “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” which ran through April of this year and aroused skeptical responses from critics who found its purported “a-historical free-for-all” more of a collection of marketable paintings of the moment.

As 2015 progressed we saw the museification of Chelsea’s mega-galleries intensify, Morandi at David Zwirner being the latest example. Even the ephemeral art form of wall painting was ripe for restaging at Gagosian, where Roy Lichtenstein’s “Greene Street Mural” was paintstakingly re-created under the supervision of the artist’s former studio assistant.

The same branch of Gagosian is currently showing Jeff Koons’s latest series, in which the artist has planted his blue “gazing balls” in front of reproductions of master paintings by Manet, Rembrandt, and others. The artist, speaking to the press, described them in relationship to “time travel,” to “parallel realities…where time and space bend.” You may wince in front of these works (I sure did), but Koons’s meta-ambitions articulate, in their way, what Chelsea has become.

An installation view of "Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Paintings," at Gagosian Gallery, New York Nov. 9-Dec. 23, 2015. Artworks © Jeff Koons. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

An installation view of "Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Paintings," at Gagosian Gallery, New York Nov. 9-Dec. 23, 2015. Artworks © Jeff Koons. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

All around town, meanwhile, other galleries known for promoting living artists excavated neglected figures from the ranks of the deceased: Pierre Klossowski at Barbara Gladstone, Alina Szaponicow at Andrea Rosen, Marjorie Strider at Broadway 1602, and Raymond Roussel at Galerie Bucholz, to name just a few.

The past-meets-present theme continued in survey shows like Greater New York, which shied away from its original mandate of celebrating emerging artists in favor of revisiting older art about the city (Alvin Baltrop’s 1970s photographs of the West Side piers, videos of Pyramid Club performances by Nelson Sullivan). And the year’s big international festival, Okwui Enwezor’s Venice Bienniale, bore a forward-looking title (“All the World’s Futures”) while taking inspiration from a backwards-facing angel (Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, as described by Walter Benjamin).

Contemporary art fairs, reliable purveyors of the new and the now, were also prone to retrospection. Frieze Masters, which promises “several thousand years of art in a unique, contemporary context,” has been around for a couple of years now—but its fourth and latest edition was, by many accounts more expansive and diverting than its sister Frieze fair, with works by Bridget Riley and Sigmar Polke cheek by jowl with Roman marbles and Renaissance paintings. NADA's editions in New York and Miami were full of stimulating work by older artists such as Dona Nelson and Katherine Bradford.

At auction and on the secondary market, the elevation of the Zero Group—so named because its members wanted to set the clock back to 00:00 in the aftermath of World War II—continued, with numerous selling shows dedicated to the movement and a record price of $29.2 million for Lucio Fontana (at Christie's in November).

Atemporality even permeated the Guggenheim’s monographic exhibition of On Kawara, he of the ritualistic, one-per-day “Date Paintings.” In place of the expected continuous chronological progression, the show gave us a more episodic look at Kawara and often seemed to be more about asserting presence than it was about marking time.

Installation view: "On Kawara—Silence," Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 6 to May 3, 2015. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Installation view: "On Kawara—Silence," Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 6 to May 3, 2015. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Other prominent museum retrospectives challenged our expectations of a linear chronology even more aggressively—notably, the Whitney’s Frank Stellashow, which mingled the rigid early stripe paintings with riotous recent reliefs and sculptures so as to avoid old formalist narratives (or disguise an off-the-rails trajectory, depending on whom you ask).

This brings us to 2016, a year in which the Metropolitan Museum of Art will debut the much-anticipated Met Breuer—a whole building full of shows that “present modern and contemporary art within a deep historical context.” And MoMA, not to be outdone, will be going non-linear next spring—reinstalling its fourth-floor permanent collection galleries with an eye to "multiple histories" (in the words of its chief curator of painting and sculpture, Ann Temkin).

We'll have to see how this marriage of the historical and the contemporary plays out. There are risks, of course; contexts may be scrambled, and modern and contemporary art's decisive breaks with the past could be glossed over in a more holistic view of cultural production. But I'm looking forward to the Met Breuer’s first show, “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,” which will unite artists from Rembrandt to Rauschenberg to explore an aesthetic of non-completion. It’s a perfectly timeless subject that also speaks to the way we see art history circa 2015-2016, as loosely plotted and fundamentally open-ended.

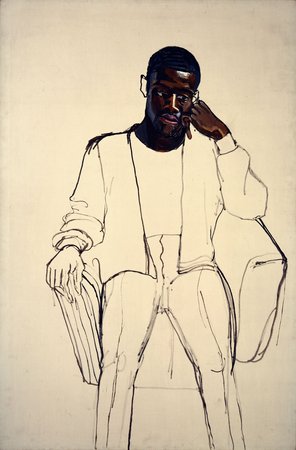

Alice Neel, James Hunter Black Draftee, 1965. Oil on canvas, 60 × 40 in. (152.4 × 101.6 cm). COMMA Foundation, Belgium © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Alice Neel, James Hunter Black Draftee, 1965. Oil on canvas, 60 × 40 in. (152.4 × 101.6 cm). COMMA Foundation, Belgium © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.