Painting’s popularity has ebbed and flowed over the years, reaching something of a low point by the late 20th century in the wake of the conceptual and “anti-retinal” movements of previous years. Some two decades later, however, the age-old medium is now experiencing a veritable resurgence as it once again fills galleries, museums, and art fairs (not to mention the eyes of critics and the walls of collectors).

Museum of Modern Art painting and sculpture curator Laura Hoptman, who since the late 1980s has served as a curator at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Carnegie Museum of Art, and the New Museumbefore settling into her current position at MoMA, experienced this shift firsthand. Indeed, it's arguable that her sustained support of new developments within the medium is at least partly responsible for the renewed popularity it enjoys today. (She's also one of the nominators for Phaidon's Vitamin P3, the important new compendium of recent painters.)

For a recent interview with Hoptman we delved deep into the nitty-gritty of contemporary painting, including especially the recent trend towards a-historical borrowing that characterizes the works of both her much-talked-about 2014 MoMA exhibition “The Forever Now” as well as the widely denounced pseudo-movement referred to as “Zombie Formalism.” (Hoptman, for the record, is a blunt critic of the latter group of artists and a firm supporter of the former, whose ranks include Kerstin Brätsch, Laura Owens, Nicole Eisenman, and more.)

In this edited and condensed continuation of her earlier conversation with Artspace’s Dylan Kerr, Hoptman recalls in highly personal terms the ideas, introductions, resistance, and unlikely connections that allowed painting to flourish anew in the 21st century. Here, in her words, is a chronicle of how painting got where it is today.

We’re very lucky to be living and working in a time when the rapid change in the cycles of art-making—coupled with souped-up systems of information-sharing—has made it easy to follow the trajectory of some of the many ideas, languages, techniques, politics, and passions that shoot in and out of one or another art discussion. Living and working in New York for several decades has helped me with this, as has my pretty traditional education in the history of art—an expertise that is based precisely in analyzing artistic trajectories.

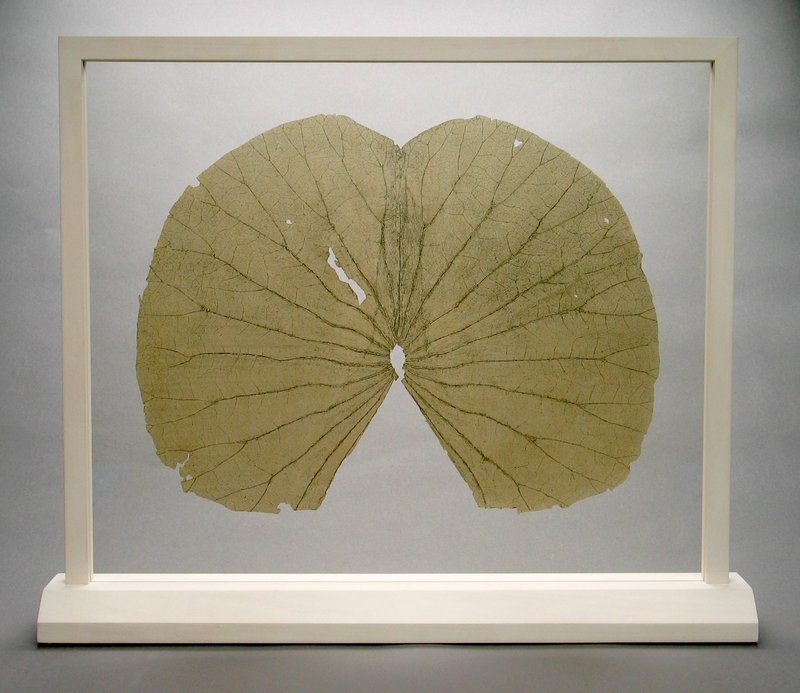

When I first started curating in the late 1980s, the artists in my generation and the couple of generations in front of me were in a moment of what I would call “narrative conceptualism.” I remember writing something around that time, saying that these artists had their cake and ate it too. I’ll use as an example an artist exactly my age, Gabriel Orozco from Mexico, whose work is conceptual but very, very visual. He’s not a painter, but the work indulges, in many cases, in the aesthetics of paintings. I don’t mean that it’s Jessica Stockholder’s three-dimensional painting—I mean there’s visual pleasure there.

Lotus Leaves (Full Leaf), 2004 by Gabriel Orozco

Lotus Leaves (Full Leaf), 2004 by Gabriel Orozco

I think this was the bugaboo, if you will, of very contemporary painting. After years of suspicion toward commodity culture, the thing that made painting politically problematic at the time was the notion that an artwork could be visually pleasurable, i.e., an object, something to consume, something that makes you happy, something that was easy, that didn’t make you work. This of course stems from the whole, wonderful period—and I’m now speaking from a New York-centric point of view, if I may—of the “dematerialization of the art object” in the late 1960s all the way up through the end of the ‘80s.

The Pictures Generation of the 1980s—when I was in college and graduate school—were the people who were as freaked out about the consumable object as they were about visual screens. They were worried about art as a high-end commodity, but they were maybe more worried about images that lied. They used the tools from literary theory to “unpack” those images to make sure that we knew they were lying. It became super important for us to know, when we looked at anything, from a painting to an advertisement, not only what it was about but how that meaning was constructed. It made it kind of futile to paint anything that wasn’t ironically taking into account that what you painted—and the act of painting was itself loaded with received ideas, prejudices, and blind spots.

In the early 1990s, the art market took a dip. It crashed. That probably put an end to the focus on some of the 1980s commodity/anti-commodity artists. It’s funny to say this, but people like Jeff Koons were not necessarily at the center of the discussion in some places at that point. We had all learned to be suspicious of images, and, besides, not many people were buying stuff at that moment anyway.

What happened in New York as a result was the revival of art spaces where artists and curators could experiment. These places weren’t not-for-profits—they were commercial galleries, but not commercial like Sonnabend, for instance. They showed new artists, but not necessarily saleable ones. Artists like Rirkrit Tiravanija, for example, had their beginnings in places like that.

Rirkrit is someone whom we now think of as the artist who created Relational Aesthetics. His type of art is not buyable—you go in and experience it. He’s kind of a fulcrum for me. At the time I met him, he was married to the painter Elizabeth Peyton. This was the beginning of my art life: Rirkrit and Elizabeth. I see them as the alpha and the omega of that moment in New York. Their work seems to be as different as chalk and cheese, but fundamentally it isn’t. What they had in common—and again, sorry to be so New York-centric here—was Andy Warhol. Both of them were inspired by Warhol’s idea that art is made out of relationships, and that its sum is community. It’s Warhol’s subject—and Rirkrit and Elizabeth’s too.

Jarvis, 1996 by Elizabeth Peyton

Jarvis, 1996 by Elizabeth Peyton

The second thing they had in common, which is equally important and part of the reason painting—and not just painting, but figurative painting—started happening in New York and other places like London right at that moment, ‘91, ‘92, ‘93, ‘94, is that both of them made art that did the opposite, in a way, of the generation that went before them. Rirkrit’s work is not an institutional critique. It is in fact devoid of irony. It is not about visual pleasure, but it is about the pleasure—the pleasure of community, and the pleasure of company.

At the same time, Elizabeth was painting these beautiful paintings of 19th-century romantic subjects—characters from Stendhal novels, poets, contemporary musicians. Her subjects were sentimental in the best way, and her colors were gorgeous. I fell in love with them. I remember the first time I wrote about them I said they were “lickable.” You just want to lick them and kiss them, because of the way they were painted but also because of their subjects. This was so not okay at the time. The other thing I said was that it was amazing that you could go and see a painting that you could just go and look at, that would just shut up and stay on the wall. It was meant to be looked at, it was meant to be admired, it was meant to turn you on, it was meant to be easy, in the sense of being a direct shot to the heart. This was pretty revolutionary, because it threw down the gauntlet for some of these late-term conceptualists and the anti-object people, in a good way.

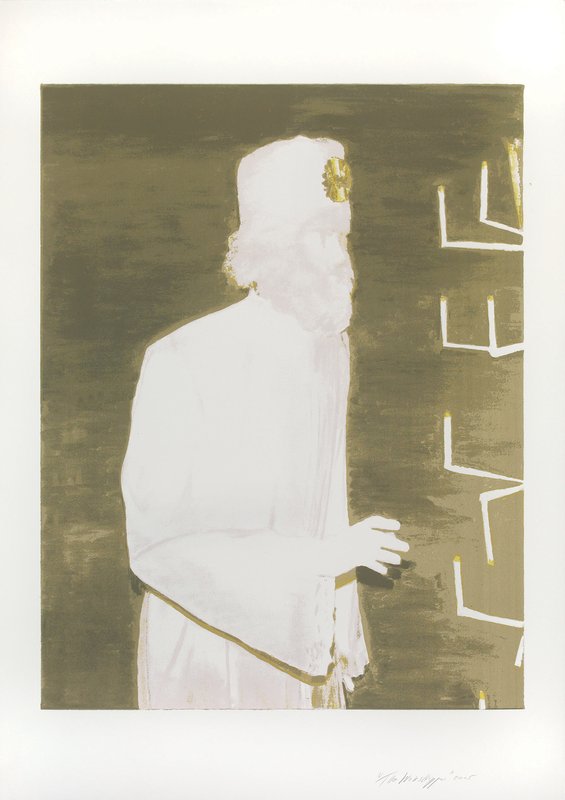

So figurative painting started happening, a little bit, at the beginning of the 1990s in New York, and I loved it. I was a friend of Gabriel Orozco, who introduced me to the work of Luc Tuymans. He brought me to the first show that Tuymans had in New York at David Zwirner, and he said, “I don’t like this, but it’s interesting.” They were these weird, muddy paintings that looked half-abstract and half-figurative on these cheap, skinny canvases with visible tacks in them on the side. You could tell the guy was very conscious of what he was doing, painting-wise—he wasn’t trying to make a luxury object. They were humble, but you could also tell that he was committed to making a painting that was of importance. It was in that show that he included a piece called Our New Quarters, which was—or seemed to be because it is, of course, ambiguous—the interior of a concentration camp bunker. For me, what Luc was doing with small paintings on cheap material was saying that painting was important enough to be a vehicle for the most difficult, impossible subject matter that you can possibly address.

The Worshipper, 2004 by Luc Tuymans

The Worshipper, 2004 by Luc Tuymans

It worked. So we had Elizabeth, who was this frankly decadent, but not decorative, painter who was devoted to pleasure, but also big ideas like love. When she talked about her work, she would talk about love—that she was in love with her subjects and that she wanted to make a painting that would embody love, and make you fall in love, too. And they did.

Then there was a third artist whose work I was looking at, John Currin. This suggestion came from my husband [Verne Dawson] who is also a figurative painter, and who, by the way, also introduced me to Elizabeth Peyton and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

When John first showed his paintings—mostly of suburban women and girls—at White Columns and later at Andrea Rosen right out of Yale graduate school, they were considered ironic and, in truth, kind of mean, even degrading, to his subjects. There were all these screeds against them as being sexist and this and that, but what struck me, again, was this reliance or belief that painting was not just an ironic vehicle, but a true vehicle.

If you think about Walter Robinson’s work and then compare it to John Currin’s, you can see the difference. Walter was—and is—product of the 1980s. His paintings are heavy with irony, heavy with exposing with how certain kinds of images of women warp our sensibilities and our idea of beauty, of glamor. The way he paints his women matches his take on those subjects. On the other hand, John was, in his own way, being true to his style and to the human body and working really, really, really hard to make it right. And in that, I thought that he was showing that he cared deeply about the housewives and students and big-boobed women—he respected them, in a way, because he respected the craft of painting so much. In other words, he was also expressing, at least to me, a belief in painting.

Altar, 2015 by John Currin

Altar, 2015 by John Currin

I am getting very personal here, because my first exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, when I was a junior curator, was Rirkrit. And my second exhibition—we have a series for young artists that young curators do called Projects—was a show that had Luc Tuymans, Elizabeth Peyton, and John Currin in it.

If I told you that I almost got fired over that show, you wouldn’t believe it—it sounds idiotic today. I remember my boss’s reaction to it: when she came into the gallery, her chin was shaking because she was trying not to cry. She said, “I hate this. I hate this!” It scared me, but it was also kind of awesome. At the time, it was felt that those three artists seriously didn’t belong at the Museum of Modern Art, even though they had just laid out where painting had been and where it was going at the moment. It was weird. Again, it’s really hard to understand that now, but that’s how large the divide was for a generation, or two generations, or three generations above us. The painting thing was transgressive, but the figurative thing was transgressive also. Put together, it really struck in peoples’ craws.

Anyway, this freedom to make figurative paintings—beautiful objects, and also accessible and saleable ones, really flourished at the end of the 1990s. The first reaction I saw to this kind of figuration was from somebody that Chris Ofilli told me to see. My husband and I were in London and we went to see this a show of paintings—lots of them—hung on the same line all around the gallery. They were small, about 14 inches high, and they were abstract. They were rendered in the ugliest colors that I had ever seen in my whole life, and they were hard-edged—there wasn’t any sort of expressionistic thing going on here. You can tell that the artist had taped things down. The work was by Tomma Abts.

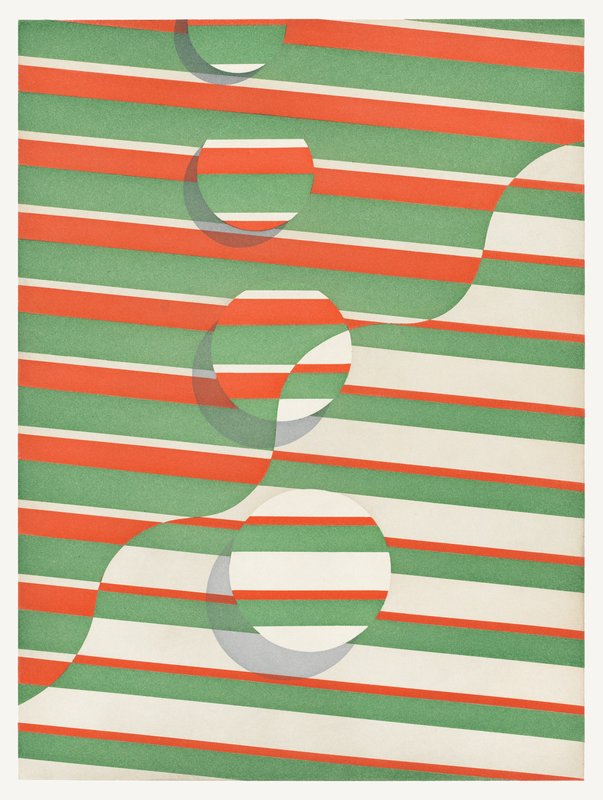

Untitled (wavy line), 2015 by Tomma Abts

Untitled (wavy line), 2015 by Tomma Abts

Tomma was, at that moment in 2000 or 2001, the perfect retort to John Currin or Elizabeth. What do you do after them and their beautiful paintings? Well, you create a picture that is about as tough and difficult, and against the taste, as you possibly can, like a mustard-colored, hard-edged abstraction. And they were fantastic. That, to me, inaugurated the second re-thinking of painting for painters of a certain generation—my age, basically.

People looked at Tomma Abts and said that her worked looked like it came from early 20th-century abstraction, but I don’t really know where her work comes from—some weird place in her brain. It’s non-objective to the hilt—there is no connection in nature or nurture to Tomma’s imagery

Mark Grotjahn started making monochromes at the same moment as Tomma’s work emerged. He was making these little signs, these masks, these figurative paintings, then he started making rainbows. From there, he moved on to the monochromes. That totally made sense. As much as Tomma made sense, as much as John Currin made sense, as much as Elizabeth Peyton made sense, it totally made sense for him to re-present, at the beginning of the 2000s, the monochrome. Again, that’s the retort to the leap to Tomma’s complicated and involved geometric abstraction.

Of course, these people weren’t the only ones painting at the time. I just went to David Salle’s studio a couple of weeks ago. He was painting away, as he always has been from the very beginning. Eric Fischl was continuing to paint. Lucien Freud was painting in London. People were always painting—I’m just talking about this generational stream, the New York stream, which happened to connect somehow to the London stream of painters like Peter Doig, and Chris Ofilli, and L.A. people like Laura Owens.

Laura is actually somebody who was on my radar in 1995, although she’s slightly different because she plays with painting. I think she believes in it, but she plays with it a lot. That almost naïve embrace of the possibilities of painting that I saw in Elizabeth and some others—that’s not Laura, especially now. Actually, looking at Laura’s career, you can see the evolution of a certain mentality towards painting. She never stopped, of course, but now she has grasped that the image on the canvas can be made in all kinds of different ways that can still be called painting, but isn’t at all positing it as the truest, most expressive language to tackle those big subjects like love and hate.

That’s where we are now, by the way. And maybe the person who showed us for sure where we are—and again, I’m sorry to be so New York-centric, you’ll have to forgive me—is probably Wade Guyton. Wade was bopping around for a number of years before people noticed what he was doing and said, “Wow, that’s interesting. He’s doing something different.” He was making sculptures, because his thing was a kind of Neo-Modernism, though I hate to use that term.

As I see it, the discussion about contemporary painting remains extremely lively and dialectical—like a ping-pong game. After Mark and Tomma, an artist like Wade ups the ante. He says, “I know—I can do this differently, by not touching the canvas at all.” At that point, I think the conversation changed. At that point, we have traveled really, really, really far from Elizabeth Peyton and this notion of a belief in painting. I think Wade took it to a place where Christopher Wool kind of already was. What he was doing was happening and had happened even as my little group was doing whatever they were doing.

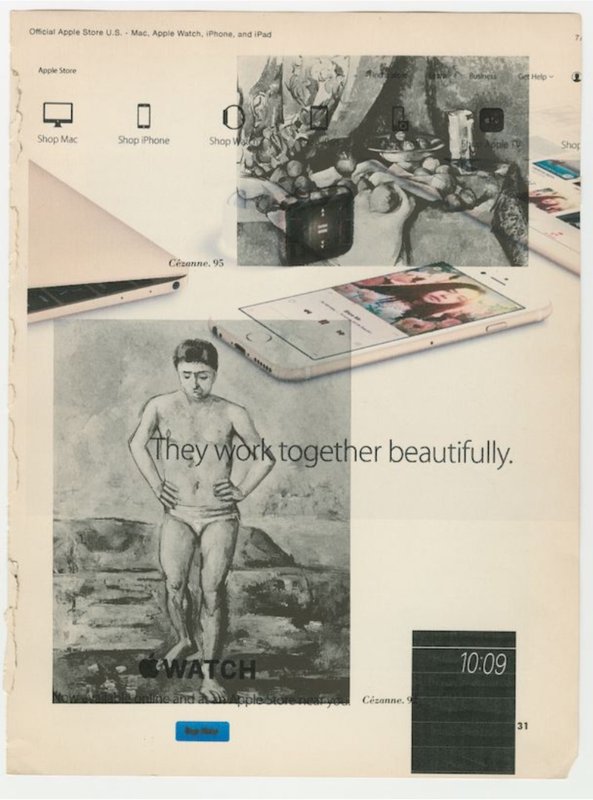

Untitled (They Work Together Beautifully), 2015 by Wade Guyton

Untitled (They Work Together Beautifully), 2015 by Wade Guyton

Christopher Wool, Richard Prince—those artists were making paintings, too, but on a parallel highway. Their work wasn’t about the belief in painting as a vehicle for the most important kinds of expressions that you could possibly make. Those guys were having a different argument, about modernism and popular culture, with painting—ironically, critically—as its platform. They were, and are, making paintings that are critiques of abstraction, of processes of expression, of the notion of the original object.

After Andy Warhol—we’ve really come full circle in this talk—all painting can’t help but be conceptual. But artists like Wool and Prince set the scene for a particular kind of conceptual painting for the digital age. I think that that argument, that line, might very well have led to Wade and lots of other smart artists who are making paintings for reasons that are really quite different than the artists of my generation. You wouldn’t want to kiss a screen, and their paintings reflect that.