One of the pleasures of collecting is knowing that, in buying a beautiful work, you can also support a great cause. Sometimes this is done by charity auctions or charitable editions, but in other instances it's simply carried out by choosing pieces by an artist who stands up for something you believe in too.

From gender equality to racial politics, the tragedy of the AIDS crisis or the societal effects of the drugs trade, these seven works all express strong personal and political positions. Hang these in your place, and you’ll be making a stand alongside the artist.

Awol Erizku – Hammer, Stick, Same Thang , 2017

By changing the skin color on the familiar Arm & Hammer baking soda logo, Erizku alters our view of this familiar household product. “Our apple pie was supplied through Arm & Hammer,” rapped Jay-Z in his 2011 duet with Kanye and Frank Ocean, “straight out the kitchen, shh don't wake nana.”

Both works are a reminder that, for many poorer and more disadvantaged African Americans, baking soda was a more familiar ingredient in the illegal production of crack cocaine than it was in the pursuit of good housekeeping. Erizku – a New Yorker of Ethiopian heritage, and a friend of Jay-Z and Beyoncé – drives home this duality with the work’s title. A hammer and a stick can mean the same thing to some people; both words are slang for guns. In opening up these dual meanings, the artist both pays tribute to the pop sensibilities of earlier decades, and creates fine art from today’s street argot.

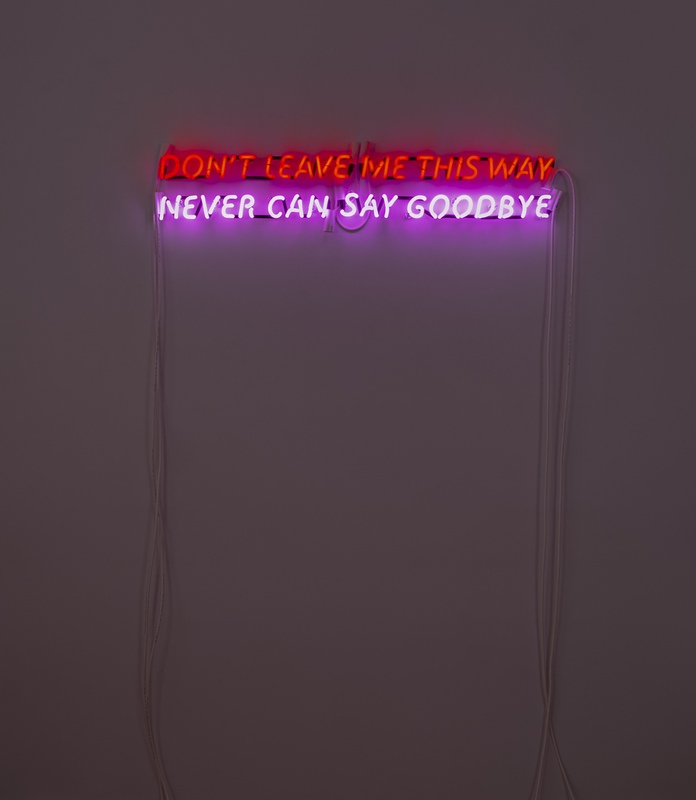

Steven Evans – Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye , 2022

For Steven Evans, the later decades of the 20th century were both the best of times and the worst of times. This American artist and curator went to his first gay bar in the early eighties at the age of 17, and fell in love with the dance music of that era. He also lived through the AIDS crisis and went on to pay tribute to many of those who passed away via Songs for a Memorial, a series of neon song-title works installed at the New York City AIDS Memorial last summer. This artwork, just like this accompanying edition, explores the intersection of language, memory, and music tied inextricably to the period surrounding the onset and height of the AIDS Crisis. Remember the songs, remember the friends, and maybe - just for a moment - let the work bring them both back home to you.

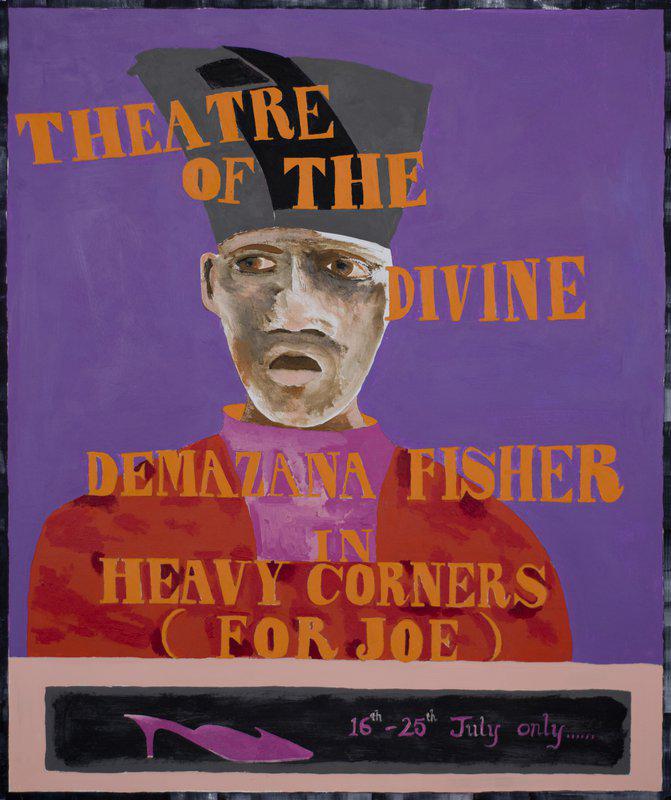

Lubaina Himid – Theatre of the Divine, 2019

Not all protest art has to be loud or in some way hectoring. The Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid was born in the Sultanate of Zanzibar (then part of the British Empire, now a part of Tanzania) and was raised in Great Britain, where she initially specialised in theater design, before dedicating herself to a life in fine art.

This print obviously pays homage to her earlier vocation, while questioning, somewhat fancifully, a person of color’s 'place within the arts'. Who is Demanza Fisher, and what kind of a play is Heavy Corners? The work's title brings to mind the confrontational theater of the absurd movement of mid-century Europe, as well as Danté’s great 14th-century poem, The Divine Comedy. Both are great cultural milestones, but both largely the work of white men. Himid’s image seems to hint at another imagined period, where cultural representation was a little more mixed.

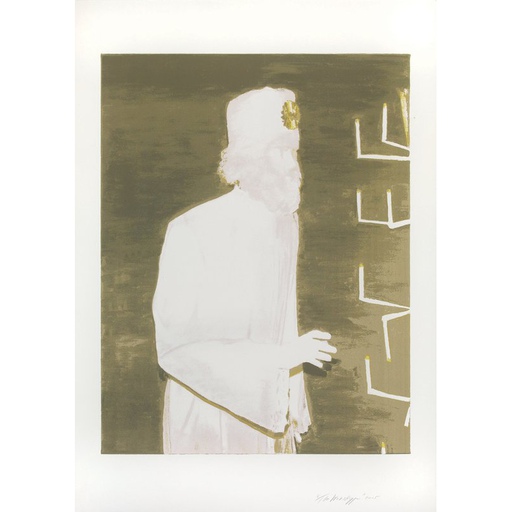

Fred Wilson – Untitled: Antilles , 2012

What might a united Caribbean look like? The American artist, educator and critic Fred Wilson takes a pass at it in this work. The Antilles – the main islands in the Caribbean Sea – are divided into many different states, each with its own flag. Those national emblems carry both vestiges of European empire building, and earlier markers of foreign cultures.

Wilson’s mash-up of these tridents, crosses and saltires, retains much of that imagery, but expresses a kind of visual creole that seems much closer to the spirit of the peoples of this region than any arbitrarily assigned emblem. Think of it as a standard to be borne for Caribbean pride.

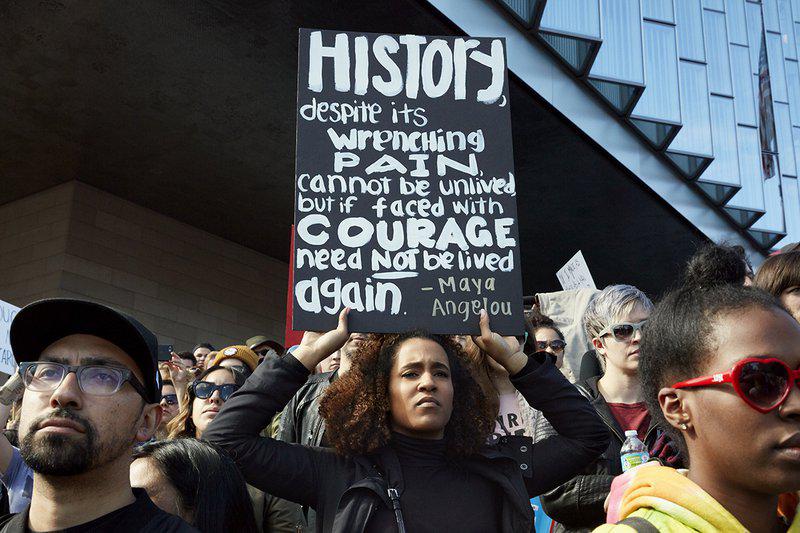

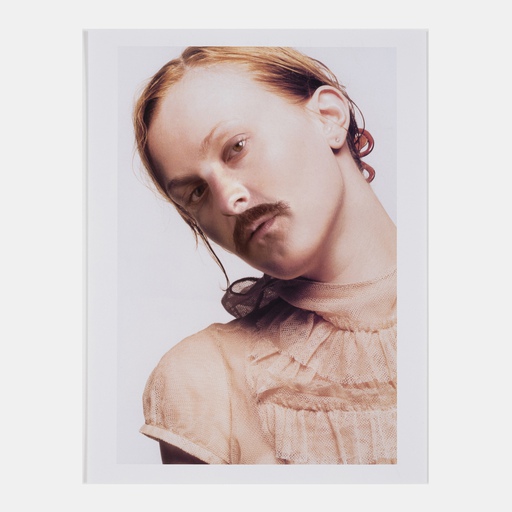

Catherine Opie – Herstory, Women's March , 2017

Catherine Opie has captured America not in its hegemonic, center ground, but instead at its margins, photographing surfers, high-school football players, lesbian families and, tea party protests.

She seems to find beauty and significance in every instance, yet in this image, taken in Los Angeles, towards the end of the first Women’s March in 2017, Opie genuinely appears to accord these everyday marchers with a higher status. The image was taken on the steps of LA’s Federal Courthouse – hence her subject’s subtle elevation – as marchers were settling to listen to speeches.

“The light was reflecting off the building across the street,” the artist told Artspace. “You just turn and you’re like OK there’s this amazing person holding this sign. I was reacting to what she was holding up. It was just a beautiful moment.”

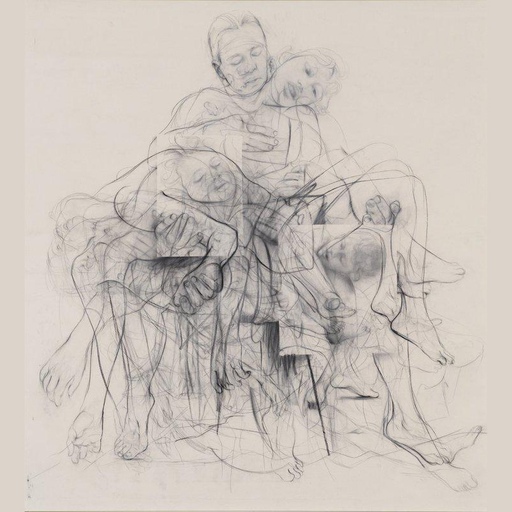

Jenny Saville – Chapter (for Linda Nochlin), 2016/2018

Like a kind of fine-art palimpsest, Jenny Saville ’s work seems to suggest both creation and erasure. Why this back and forth? A clue lies in the title. Linda Nochiln is the acclaimed US art historian who wrote the 1971 article, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? , in which she outlined the institutional barriers that held women back from succeeding within the arts.

Saville has successfully negotiated those barriers; the British artist’s works have sold at auction for millions. However, the reworking of the figures in this piece perhaps speak to the tireless labour many female artists have carried out, outside of the canon.

Ebony G Patterson – Untitled (Among the weeds, backpack, shoes, and stones) , 2015/2018

It’s pretty hard to see the body in among all that color and embellishment, and for Ebony G Patterson , that’s sort of the point. This Jamaican artist’s neo-baroque works may look pretty but they address the ugly topics of racial injustice, violence, masculinity, and visibility and invisibility, both in the post-colonial context of her own country and within black youth culture more generally. No viewer could deny the simple beauty of Patterson’s pieces; and on closer examination, no one could ignore the prone body hidden within them.

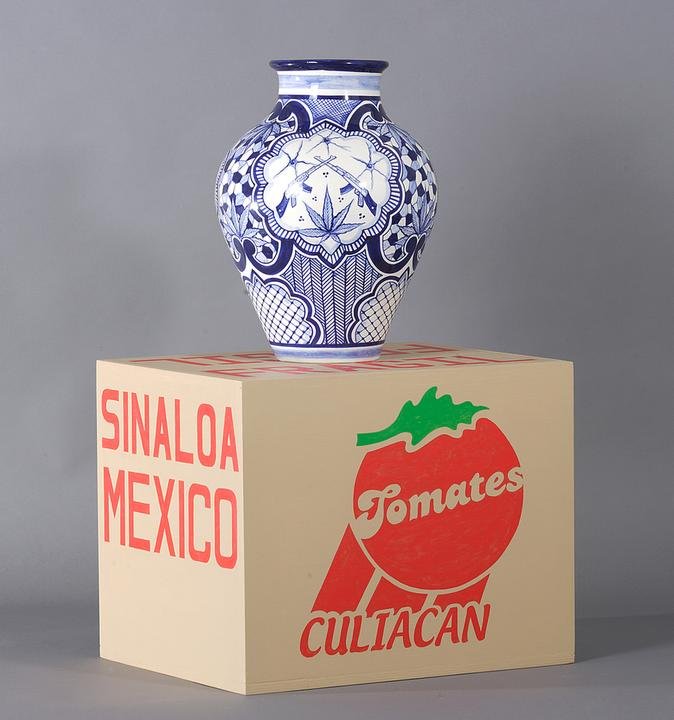

Eduardo Sarabia – Desert Dreams, 2013

What do we bring across borders? And how do we shape those places that serve as our exporters? Eduardo Sarabia , a Californian artist of Mexican heritage, toys with these ideas in Desert Dreams, by taking the traditional Talavera pottery, popular with so many visitors to Mexico, and embellishing it with symbols of the narcotics trade – another Mexican export that has scarred so much of the country over the years. The pretty, poppy work (also reminscent of Warhol's Brillo Boxes) retains its ornamental beauty while raising hard questions about cultural and economic relations.

Check out all of these works and more in the Artspace gallery .