Gianni Jetzer has built his career around always knowing what’s next. As director of the Swiss Institute in New York from 2006-2013, he shifted the space’s programming away from its focus on national identity toward a more all-embracing vision of contemporary art, exhibiting non-Swiss artists on the rise such as Jordon Wolfson and Ryan Foerster. He’s also helmed Art Basel’s Unlimited section since 2012, where he’s raised the bar for what’s possible in an art fair by consistently bringing stunning and often massive displays of museum-quality work.

Now, as curator at large for the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Jetzer is on a mission to update the institution’s collection for the 21st century. Although the ostensible theme of his current exhibition “Suspended Animation” is digital modeling and simulation, the curator is less concerned with animation as an art form than he is with how we, as people with bodies made of flesh rather than pixels, are taking up new digital tools. The show features works by Ed Atkins, Antoine Catala, Ian Cheng, Josh Kline, Helen Marten, and Agnieszka Polska, six of the most recognized young artists working in the medium today; in Jetzer’s hands, these works help us navigate the seismic shifts that characterize our contemporary media culture.

Recently, Artspace’s Dylan Kerr sat down with Jetzer to discuss his fears of a video-game-character revolution, why Relational Aesthetics is a reaction to the Internet, and how animation helps us leave our "annoying" bodies behind.

How did you settle on the subject of digital animation?

In the beginning, I was really interested in the phenomenon of animation as a whole. If you board a plane, the safety video is an animation. If you look at Hollywood or even independent films, directors already work with animation and are interested in this kind of reinterpretation of reality that is in-between, that is not just actors playing roles but rather another tissue of reality over that action. All of a sudden, artists were able and willing to use that technology and were using it in interesting ways.

Today, so much of contemporary art is about re-chewing existing ideas. Of course new things come out of that, but it’s also important that we have a generation of artists who embrace the future and ask new questions that we don’t really have answers for. I wanted to have artists in the show who, although they’re all young and only have a few years of artistic production behind them, are really leading voices of their generation. The Hirshhorn is a more mature contemporary art museum, and I don’t think we should be doing ICA or kunsthalle-type shows here—there should be a certain maturity.

I also wanted to limit the subject matter, because I didn’t want to have a show that is based just on the medium of animation. Rather, I was fascinated by the whole notion of the body facing this new digital technology. It’s about the digital doubling of the body, the introduction of fluid digital characters that we relate to and that exist. Their form of existence, the missing physicality of their body, is to some extent a challenge to the viewer, who has a carnal body that is facing these fluid, electronic bodies.

Where did the title “Suspended Animation” come from?

The term "suspended animation" originally comes from science fiction, and now medicine as well. Emergency rooms have started to cool down patients in order to repair them without damaging the brain through lack of oxygen, which is similar to the fictional use of suspended animation. For me, the present is like suspended animation 2.0. It’s not the science fiction chapter anymore—we’re part of it now. The body is suspended, to a certain extent, because these digital worlds have opened up such amazing possibilities for being present in wholly new ways.

Still from Agnieszka Polska's I Am the Mouth, 2014.Courtesy of ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin

That's interesting, because people often talk about digital artworks in terms of the mutability rather than the stability of the body. How are these artists invoking suspension?

In medicine and science fiction, the aim of suspended animation is to overcome the limits of the carnal body to achieve an unlimited physical state. In digital art, the problem is re-solved altogether, because the nature of those bodies is radically different. What’s really interesting about these artists is that they work with different aspects of this idea—it’s always these avatar bodies, but each artist is addressing a different subject.

For example, the first organism that you encounter in the show is a huge set of disembodied lips by Agnieszka Polska. The work reproduces the techniques used in an Internet phenomenon called ASMR, which are videos that often use a very soothing voice speaking at a whisper to trigger a physical reaction in our bodies—people describe the experience as a kind of tingling sensation. Polska’s work plays with this strange interaction between electronic communication and bodily sensation. You can look at her lips as a body optimized for communication, which is itself a kind of sensation. Even what the lips are saying, the information, is nothing else but the description of communication—it’s totally self-reflective and optimized in that way as well.

Later in the exhibition, you encounter a new work by Antonie Catala that consists of an inflatable pneumatic screen with footage he recorded of models projected onto this surface. Those models are the only bodies in the show that are real flesh-and-blood, and they’re being projected onto this other, breathing body. This is another state of bodily representation that I think will be very important within the exhibition—it’s going to break the assumptions you might have made after having seen the earlier works.

The relationship to the body that you're describing is a defining characteristic of Post-Internet art. Were you thinking about that term at all?

I’m not so interested in the Post-Internet label, because it doesn’t really match what the artists are doing. All of the artists in this show work in different mediums. I’m more interested in the fact that they’re using computer animation to transport matter and pose questions of embodiment and disembodiment in connection to digital culture.

Technology has always influenced our notion of the body, from cinema to the computer. There’s a whole history of Modernism in which the photographer’s body merges into the camera—now we compare the human brain to processors and hard drives. On the other hand, we still define ourselves through the uniqueness of our physical bodies.

I think that this idea is being challenged right now—why should we limit ourselves to this annoying, carnal state? We’re already overcoming it, to a certain extent. Even with such simple programs as Skype, we have a form of communication that is much more connected and goes far beyond what the telephone was able to bring. Going even further, there’s a whole discussion in cinema now about whether actors own their digital avatar. Actually, an actor doesn’t—it’s owned by whoever created it, which is quite extreme. I think the more the body is mirrored and measured digitally, the more our notion of the carnal body gets rerouted and questioned altogether. A lot of works in the show actually relate to that change of tissue in reality.

Still from Helen Marten's Orchids, or a Hemispherical Bottom, 2013. Courtesy of the artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Greene Naftali, New York; Johann Koenig, Berlin; and T293, Rome/Naples

How so?

We can look at Helen Marten. She’s only done a couple of animation works—it’s more of a side project to her sculptures and installations. Her piece in the show is very much about insecurity, because the fabric of known things has changed. It’s almost a still life, but the objects are not authentic anymore. The body in the piece comes out of nowhere, and so do all the objects. They’re composed out of the artist’s fantasy.

It’s a form of animation that is totally new, and that actually takes the lead in that it doesn’t try to reproduce reality. Rather, it generates a new reality itself that can’t really be compared to anything else. In cinema there’s a whole conversation around what’s called the uncanny valley, but I think with artistic videos, in most of the cases, that problem doesn’t come up. It’s an artistic interpretation of reality that is off anyways, and that goes far beyond what we would experience as reality.

The digital modeling technologies the artists in this show utilize have reached what is perhaps their zenith in the context of video games, which have evolved from 8-bit pastimes to multimillion-dollar blockbusters. Do you see the impact of this medium in any works in the show?

Most galleries at the Hirshhorn are circular, but this show is in the sub-level galleries. It’s going to be a strange course, with glass doors in between each artists such that there’s never a hallway. You enter almost like a video game, where you progress from one level to another with no way to escape. In a game, you can just say “game over” and you’re out, but here you have to go deeper and deeper into the tissue of the show until you come out—it’s a U-shaped exhibition, basically. You move from Polska’s mouth, to Helen Marten’s still lifes, to Ed Atkins’s very strange loner, to a new piece by Antonie Catala, to Josh Kline’s animations, and end with Ian Cheng’s simulation.

In Cheng's work the video-game influence comes through very strongly, but there’s a big difference in his work versus the others because it’s inherently dynamic. With his piece, the viewer becomes a kind of cyber-anthropologist, watching a simulated tribe of digital beings and trying to understand how they function.

I like that at this moment where we’re all trying to understand digital life and digital creativity, this exhibit focuses on the discovery of digital consciousness. This piece relates strongly to game culture, where we play against digital characters that are self-steered, who make their own decisions and have their own opinions. It can be quite extreme—what if they really become independent and leave the system of games to enter real networks of communication or defense or power plants?

Still from Ian Cheng's Emissary in the Squat of Gods, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

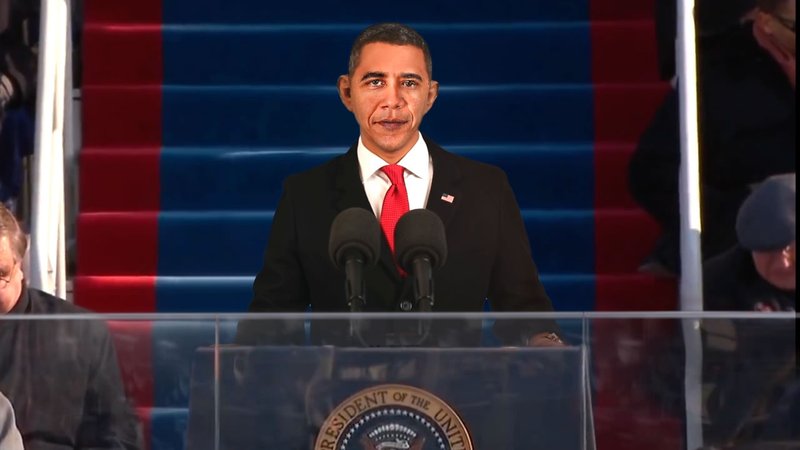

Other works in the show, like Josh Kline’s Hope and Change—which received a lot of attention when it was shown in last year’s New Museum Triennial—seem to be borrowing more from the overwrought digital graphics of news shows and the like.

It’s hard to believe how little it takes to influence us. The whole image of the president addressing the nation is very strong and very iconic. Josh hired the most famous Obama impersonator, Reggie Brown, and then used facial substitution software to paste Obama’s features on top of his face. It’s strange to see this Frankenstein-like digital creation—suspension of disbelief is often key to Klein’s work—but it still seems credible.

Obama’s form in this piece breaks with the idea that a body belongs to a person. Here, it seems to belong to at least two people, and perhaps anyone else who can use the software. What’s interesting is that Kline also includes references from the future along with the then-present, 2009. Because he knows better, the Obama character is able to react proactively against future chapters of his presidency, like mass shootings. This mixing of the time axis is actually an attack on truth—the idea of present versus future seems to be dissolving along with the body, as everything ends up in a big, indecipherable mash-up.

That idea seems to be in line with the current move toward atemporality in contemporary art. Why do you think now is the time to put together a show of these kinds of works?

There are different answers to that question. The simplest answer is that it took some time to make that technology available to artists. In the ‘70s, it was driven by places like the University of Utah, which was very important for digital animation. Later, it moved to Pixar and the entertainment industry. Now it’s become far more accessible for everyone, including artists, which is a crucial condition.

Since the ‘90s, technological innovation and the rise of the Internet have had a huge influence on artistic creation. I think the whole subject of acceleration, which was very big in the second half of the ‘90s, can be seen as a response to these developments. Even Relational Aesthetics can be seen in the context of this new mode of electronic communication, a reaction to the fact that we spend a lot of time speaking to each other through computer screens. Relational Aesthetics stresses direct experience and direct communication—it’s very analog in that way.

Still from Josh Kline's Hope and Change, 2015. Courtesy of the artist; 47 Canal, New York; and Candace Barasch

For a long time, using these technologies were segregated under the category of media art, which very often showed artists working with new tools the way a painter works with paint and canvas. I don’t think that’s really the point—I think all the people in the show are artists who made the choice to use these new media technologies as very efficient channels to transport certain ideas. For instance, Kline has an interest in politics in general, especially how they impact the new mass media. Cheng studied cognitive science, so you can tell that he’s very interested in the development of consciousness in relation to the development of digital technologies.

I think part of the success of my invitation to the artists was that I didn’t approach them by saying, “I want to have Post-Internet artists who work with new technology.” Rather, I told them, “I want to investigate the state of the body in the context of digital representation.” I think that’s the strength of this show—we have examples of this investigation that vary a lot from each other, but you also have a kind of golden thread that weaves through the whole show. It’s always about the depiction of the body, strategies of embodiment, and moments of disembodiment. That’s the force field within which everything is happening.

How do you see these pieces fitting into the larger conversations happening in the art world now?

When the Apollo mission went to the moon, they hired Norman Rockwell to depict the milestones of the mission in part because they distrusted photography. They thought that one day the photographs could be destroyed due to chemical instability, while an oil painting can be stable for centuries and centuries. That’s an important idea today, because the stability of memory systems in terms of electronic communications is not secure right now. There are still so many question marks.

I think our generation is part of a revolution, and it’s quite difficult to predict what’s going to happen. Art history is strongly related to the sharing of images and the iconic value of imagery. Through the enhanced distribution of images online, nothing is what it used to be. The Internet is the most efficient image-propulsion system that I can imagine. It’s fascinating to watch how art history gets reshaped by the fact that images are just out there—artworks can be a big success even if they are 200 years old. At the same time, a whole new valuation of imagery is taking place, especially through social media—it’s all about clicking, basically, liking and disliking. They have calculated that the average museum visitor spends 15 to 30 seconds in front of an artwork in a museum, so an Internet user probably spends 1 to 3 seconds on a digital image. This is part of the revolution, too.