“I want to be known as a British male artist or an American white male artist, because they get a lot of attention,” the Egyptian-born artist Ghada Amer says in Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath’s recent book Summer, Autumn, Winter and Spring: Conversations with Arab Artists. “They don’t have shows like ‘Women Artists in the 21st Century.’”

Amer is known for her equally wry and provocative embroidered paintings, which rework pornographic source material to address the oppression of women and explore female sexuality from a feminist angle. In the past few years she has moved from painting into sculpture, experimenting with bronze and, most recently, ceramics—an increasingly popular medium and one that, like embroidery, that has long been associated with craft and female labor. Some of these new works look like details taken from Amer’s paintings; women gaze seductively at the viewer, smoke, kiss, caress, or masturbate.

Amer's experiments with sculpture have been well received. When Doha’s Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art commissioned her to create a work as part of their debut show in 2010, Amer produced One Hundred Words of Love, a spherical resin sculpture comprised of all of love’s synonyms in Arabic. She then took up bronze casting, and one of her bronzes was subsequently acquired by the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and shown at the museum’s inaugural exhibition in the UAE capital last November. And for the past two years Amer has been an artist in residence at the nonprofit New York ceramics studio Greenwich House Pottery, where she has been honing her skills in private classes. She is now renovating a larger studio to accommodate her new sculpture practice, to share the space with Reza Farkhondeh, the Iranian-born artist with whom she often collaborates on paintings.

With a show of Amer's ceramics inaugurating Leila Heller’s brand new Dubai outpost, Myrna Ayad caught up with the artist to talk about her new favorite medium and what it's like to be a feminist figurative artist in the Middle East.

The Sleeping Girl, 2014. Ceramic, 33 x 30 x 7.5 in / 83.8 x 76.2 x 19 cm. Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

The Sleeping Girl, 2014. Ceramic, 33 x 30 x 7.5 in / 83.8 x 76.2 x 19 cm. Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

What made you want to take up sculpture, after many years of working with painting and embroidery?

It started with an abstract idea. When I worked in bronze it was because I wanted to do a hollow sculpture, and then when I did ceramics, it was because I wanted to do sculpture in colors.

Working with ceramics was quite the game-changer. I love to experiment, but I couldn’t do it in my bronze works; there was a team doing it and I felt handicapped because I like to be hands-on. Also, it is very expensive to get someone to do it for me and when you pay someone, you can’t experiment.

What were some challenges of learning a new medium?

There was a lot of sweat and exercise, and my back hurt! In the beginning it felt disgusting, but now I love it—I love putting my hands in the clay. It doesn’t feel ‘dirty’ anymore.

I thought I knew how to do everything, and figured I only needed three months to learn how to do ceramics. I was so arrogant! Greenwich House Pottery offered me a residency for two years, and it ended in August. I’m exhausted, but at the same time so upset that a great experience is over. I’d go twice a week to class and then practice alone—no wheel, hand-building only.

Froissé, 2014. Ceramic, 9.5 x 7.5 x 8 in (24.13 x 19.05 x 20.32 cm). Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

There is a new physicality involved in this experimentation, and also new devices. What is the synergy like between material and machine?

It’s all about the tool, and the vocabulary of clay. I am discovering a new medium. I like the spontaneity of just doing. I color first, and then I carve. And this is a great feeling, because my hands are used to drawing—they’re not used to forming something.

Study in Yellow, 2015. Ceramic, 6 x 9.5 x 4 in (15.24 x 24.13 x 10.16 cm). Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

What happens to your drawing while you’re working on the ceramics?

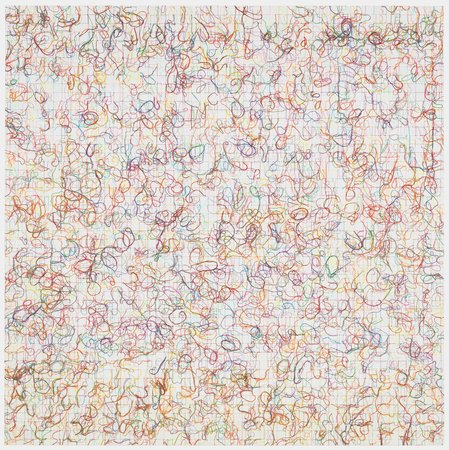

I still paint, and my method has been impacted. Ceramics mean a lot of experimentation, especially with color. You have to do a lot of testing before you make a piece. What I am doing now with my paintings is that I experiment in the same way before I make a painting. I did not do that before.

How has working with ceramics changed your understanding of color? With ceramics, colors can change as the piece is baked and glazed.

Ceramics is science—it’s chemistry. I struggled with color and did a lot of tile testing. For some reason, I can’t find the right green or purple! That’s why there isn’t any green or purple in the works. I don’t paint with glaze, and natural colors such as brown don’t interest me—they’re so limiting. I will be showing new paintings at Cheim & Read soon, and I have applied the same techniques from ceramics to the paintings. Basically, I used something that I wouldn’t have been able to use had I not done ceramics.

Lady in Black, 2015. Ceramic, 48 x 22 x 10.5 in (121.92 x 55.88 x 26.67 cm). Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

How have your dealers reacted to your interest in ceramics?

It was bit of a battle, in a way, in that it’s a new market and I didn’t feel much enthusiasm from them, although people helped me with logistics. Adam Welch, the director of Greenwich House Pottery and my mentor, was really behind me. In the Middle East, however, people are more interested in innovation.

How did the collaboration with Leila Heller come about?

I’ve known Leila for a long time, and I'm very impressed with what she’s doing for the Middle East and in the Middle East. When she asked me to do this, I wanted to support her. A gallery in the Middle East has never approached me. Leila is brave—she is making a statement with this show.

White Squares, 2013. Acrylic, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 50 x 50 inches / 127 x 127 cm. Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

White Squares, 2013. Acrylic, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 50 x 50 inches / 127 x 127 cm. Photo: Brian Buckley, courtesy Cheim & Read and Leila Heller Gallery

Speaking of which, some of your more erotic works may be have to be censored, due to the laws in Dubai. How are you dealing with this restriction?

I can’t show some of the work I love. I do have to censor myself in the show, but I’ll be showing works that incorporate writing. One is a collaboration between Reza and I that says "man fucks woman, subject verb object," and the others feature text from Simone de Beauvoir and the Arab feminist, writer, activist, and physician Nawal Al-Saadawi.

Even some of your new abstract pieces look very sensual. Is this what you intended for them?

While making them I carved the clay with a tool and, then grabbed what I carved with my left hand. Then when I looked at my left hand, I discovered that the left hand was making ‘unconscious sculpture,' a little like ecriture automatiques. I loved that there was something kind of automatic about them. With sculpture, you plan everything; these are more like Expressionist paintings, more spontaneous. There’s a lot of feeling.