When a fiercly independent and beautiful young women fell into the arms of Vogue (literally... you'll see how), she probably never imagined it would lead her into yachts and penthouses, then into trenches and concentration camps, and then, strangely, into the bathtub of Adolf Hitler hours before his suicide. Sound like the plot of a movie? It darn well should be! Instead, it's the actual life of Lee Miller (1907-1977), whose endlessly fascinating life inspired endlessly fascinating art, much of which remains under-known. After modeling in front of the camera, Miller became a photographer herself, working alongside Man Ray in Paris, inventing new photo developing techniques and making surrealist images she often never received credit for. But that's just the half of it.

In our series of articles that look in depth into historic artists you’ve probably never heard of, here we look at the life and work of Lee Miller.

A Traumatic Childhood

Born in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1907, Miller was struck with a ongoing landslide of misfortune. Her mother became ill when Miller was seven years old, and unable to be cared for, she was sent to live with family friends in Brooklyn. There, Lee was raped by the family’s son. To make matters worse, the rape left her with a venereal disease that required years of excruciating treatments. She also saw a psychiatrist, which at the time was rather rare, who encouraged her to view sex as a purely physical act and not one tied to love, in an effort to thwart feelings of guilt or wrongdoing that she may have had. Miller kept this abuse a secret for her entire life. Soon after the assault, Miller began modeling for her father, an amateur photographer. While this may have primed her for her career as a muse, the fact that her father asked her to pose nude from the ages of eight through twenty, was suspicious to say the least.

Lee Miller as a young girl. Date and photographer unknown. Image via Tumblr.

Lee Miller as a young girl. Date and photographer unknown. Image via Tumblr.

An Accidental Star Is Born

With her long, slender neck and glistening blue eyes, it's not so surprising that Miller found success as a model. How she became discovered, though, is almost too hard to believe. One night when Miller was 19 years old, she left her brownstone apartment on Manhattan's West 48th Street and was almost hit by oncoming traffic as she crossed the street. Luckily, a man grabbed her and pulled her to safety. That man? The publisher, Conde Naste.

The rest is history: just a few months later, Miller was on the cover of British and American Vogue. It wasn’t long before Miller was rubbing elbows with New York’s glitterati: Josephine Baker, Cecil Beaton, and Fred Astaire to name a few, as well as Charlie Chaplin, one of her many suitors. She would spend the next two years modeling for Vogue (she was photographer Edward Steichen ’s favorite model), and as par for the course, spent time in the lavish Vogue penthouse dressed in furs and jewels while in the city, and in the country, sailed on yachts and flew in two-seater planes.

Lee Miller, photographed by George Hoyningen-Huene, 1932

Lee Miller, photographed by George Hoyningen-Huene, 1932

A Creative Thirst Quenched in Paris

Though Miller may have been living like a star, a life many of us dream of, she wasn’t content with her role as a rather passive actor in the field of fashion photography. In 1929 she found the inspiration she yearned for when Steichen showed her the photographs of Man Ray , an artist known for his contributions to Dada and Surrealist photography in both the United States and Europe. So enthralled with his work, Miller left her home and modeling career in New York and traveled to Paris with the hope of making Ray her creative mentor. Miller eventually found Ray in a Parisian bar after several weeks of searching for him. With letters of introduction in hand, she reportedly introduced herself to Ray like this: “My name is Lee Miller, and I’m your new student.” Ray explained that he wasn’t interested in having a student and that he would be vacationing in Biarritz the next day anyhow. “So am I,” she replied. Enthralled with her beauty, her brazen, or both, Ray was smitten, and the two spent the next three years together. Miller was his lover, his muse, his model, and his student.

Lee Miller and Man Ray. Image via the Lee Miller Archives.

Lee Miller and Man Ray. Image via the Lee Miller Archives.

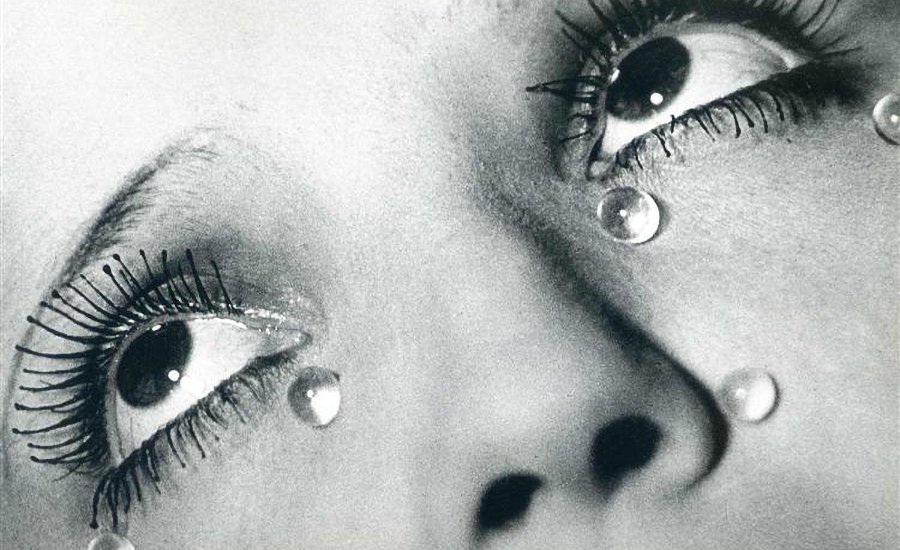

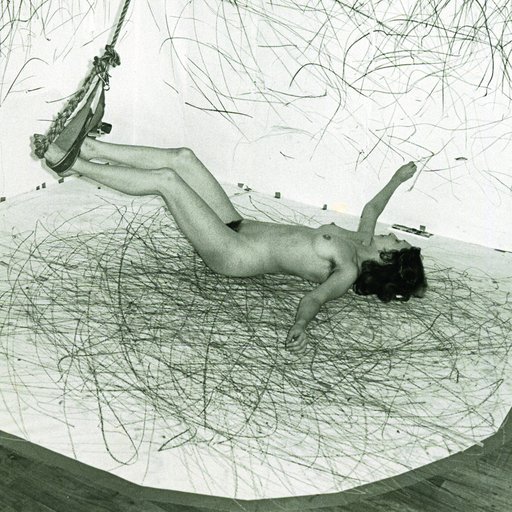

Experimental Photography

As often was the case in the male-centric art world of the time (...and today), Ray was often credited for work that he and Miller created together. His “solarization” images, which are celebrated for their otherworldly glow, as if the nude subjects within them were radiating with light, were created by exposing the prints prematurely to light in the dark room. While Ray and Miller would eventually flicker the lights intentionally to reproduce the affect, the process was first accidentally stumbled upon by Miller, who made a "mistake" in the darkroom.

When Ray had commercial clients he didn’t feel like laboring for, Miller would take the reigns, working under his name so that he could continue to focus on his more artistic pursuits. In this case, Miller literally did Ray's work for him. And, of course, Ray took hundreds of photos of Miller, his muse, which he profited off of.

Lee Miller,

Exploding Hand

, 1930. © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. Image via Miami New Times

Lee Miller,

Exploding Hand

, 1930. © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. Image via Miami New Times

But, if you haven't picked up on this already, Miller wasn't the type of person to be content living in the shadow of someone else's wing. Miller soon set up a studio of her own in Montparnasse, where she had clients like Jean Patou, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Coco Chanel. She also expanded on her role in front of the camera, playing the lead in The Blood of a Poet , a much-celebrated Surrealist film by Jean Cocateau. Jealous, Ray became possessive over Miller (he thought of Cacateau as his rival), which was something Miller wasn't willing to put up with. Once again, flying the coop of comfort and stable work, she left her home (and Ray) in Paris and moved back to New York to maintain her independence.

In New York she thrived, in part thanks to her Conde Naste connections, and in 1934 was hailed as one of the most “distinguished living photographers” by Vanity Fair. However, her ascent was put to a halt (or at least a temporary stall) when she became reacquainted with an Egyptian by the name of Aziz Eloui Bey, who she had met previously in Paris. Swept off her feet, she married him almost immediately. Miller closed her studio and moved to Cairo. Though she stopped working commercially during that time, she continued to take photographs, documenting the life around her. It didn't take her long to become tired of life in Cairo (and perhaps of her husband as well), so Miller travelled to France frequently, spending her time in the company of Pablo Picasso (her sometime lover) and his friends. During this time, Miller was a prolific fashion photographer, shooting for British Vogue.

Lee Miller,

Shadow of the Great Pyramid

, 1938. Image via Pinterest.

Lee Miller,

Shadow of the Great Pyramid

, 1938. Image via Pinterest.

The War

In September of 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany after the Nazi army invaded Poland, and Miller found it harder and harder to focus soley on fashion. According to W Magazine, Life photographer David E. Scherman, who Miller had dated, said that the prospect of "being left out of the biggest story of the decade almost drove poor Lee Miller mad." Whether inspired by vanity, boredom, politics, altruism, or a combination it all, Miller applied for accreditation as a war correspondent.

Miller became the only female combat photographer in Europe during the war, and her contributions to war journalism were unparalleled. Miller joined the 83rd Infantry Division of the US Army, and was in the front line of the Allied advance from Normandy to Paris. Years later, Miller's son Antony would say of his mother, "The GIs liked her—they saw her as a good buddy. She could swear as well as they could, and put up with being under fire." Here's an excerpt from Phaidon's upcoming book Issues , which describes the June 1945 issue of Vogue , and the shocking yet delicate handling of the violent war within the context of a fashion magazine:

"The issue opens with [a drawing by Eric (Carl Erickson)], of the Statue of Liberty in a shower of roses, and news photos (one by Weegee) of ticker-tape parades and cheering, marching crowds. Model-turned-war-correspondent Lee Miller's pictures of smiling Russians and American forces meeting in Torgau, Germany, 'linked for Victory,' continues the optimistic mood. But she breaks it abruptly with an article headlined "Germans Are Like This" and five pages of photographs telegraphed from Germany.

"Miller's shot of a pile of skeletal bodies at Buchenwald would be shocking in any context, but imagine coming upon it in the middle of your fashion magazine. Miller's headline here, 'Believe It,' is as blunt and unsparing as her pictures, including startlingly intimate images of Nazi suicide and humiliation. 'I usually don't take pictures of horrors,' she writes. 'But don't think that every town and every area isn't rich with them.' Infuriated that the Germans imagine themselves 'a liberated, not a conquered people,' she's also quick to note revealing details that a Vogue reader, who'd learned to do without wartime luxuries, would appreciate: a woman's 'too good leather shoes,' one city's abundance of 'fur coats, silk stockings and fiercely ugly hats,' and the news that 'well-bred women didn't wear fur coats during war, because every factory girl and prostitute in Germany was wearing one—stolen from Paris.'"

Lee Miller, Buchenwald, Germany: Guards Beaten by Liberated Prisoners, April 1945. Image via Pinterest.

Lee Miller, Buchenwald, Germany: Guards Beaten by Liberated Prisoners, April 1945. Image via Pinterest.

What the issue doesn't mention, is that the day Miller "shot a pile of skeletal bodies at Buchenwald" (yes, Miller was one of the first to discover concentration camps), is that later that day, she travelled with troops to Munich, and broke into Adolf Hitlers apartment. In a move that could seemingly only be done by the one and only Lee Miller, the journalist removed her boots and clothes, caked in mud from the concentration camp earlier that day, and soaked in the tub in Hitler's bathroom. And of course, she photographed herself doing it. See the evidence for yourself (and note Hitler's portrait in the background):

Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub. By David Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images. Image via Vanity Fair.

Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub. By David Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images. Image via Vanity Fair.

Of course, Miller couldn't have known that just hours after the photograph was taken, Hitler and Eva Braun would commit suicide in Hitler's bunker in Berlin.

Legacy

After the war, Miller became pregnant with collector and Surrealist artist Roland Penrose, who she married and moved to New York with. Suffering from what is now recognized as post traumatic stress dissorder, Miller was never able to recover from her experiences on the front lines. Like so many war veterans who lacked professional psychological rehabilitation, Miller self-medicated and became a deeply depressed alcoholic. Her son describes his difficult childhood in W Magazine: "It's not easy to have a relationship with an alcoholic parent... She was normally a very generous, sensitive and kind person, but when drunk she would be verbally abusive and cutting... She never hit me—she didn't need to. She could do all the damage with words." As Antony grew older, he distanced himself from his mother, who had never spoke with him about her former life as a model, artist, and war correspondent.

As Miller got older, she was able to recover, at least partially, from her depression and alcoholism, and reinvented herself as a gourmet Surrealist cook, tantilizing guests with dishes like blue spaghetti and cauliflower colored to look like breasts (nipples included!). But it wasn't until after her death, when her son discovered her archive of photographs, negatives, and old Vogue issues in her attick, that Antony discovered who is mother really was. "Until then, I'd seen her as a booze-soaked, hysterical woman. I had to re-evaluate my entire attitude to her." Miller even kept her childhood abuse secret. "When I told my father," Antony said, "it was an incredibly touching moment. He said, 'I wish we'd known—it would have enabled us to understand."

Tragically, at the time that Miller died (of cancer at the age of 80), she enjoyed little celebration for her astonishing achievements. (Man Ray's fame continued to increase, and he's extremly well-known today.) Since, though, Antony has devoted his life's work to restore her reputation. Having made her archive available to the public and having written biogoraphies on both of his parents, Antony has helped his mother's work gain appreciation, in the process uncovering the mother he never fully knew, learning about her courage, fierce independence, and spirit through the very work that took it out of her.

RELATED ARTICLE: