William Wegman and his Weimaraners have entered the homes of millions—via Sesame Street, Saturday Night Live , and Johnny Carson ; via posters and calendars and prints. But while Wegman is best known for dressing his dogs like people, he started his career as a conceptual artist. Currently on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is "Before/On/After: William Wegman and California Conceptualism." Wegman donated 174 of his videos, which he made between 1970 and 1999, to the museum—the occasion for this exhibition. In addition to wall works by Wegman and artists like John Baldessari , Vija Celmins , Douglas Huebler, and Ed Ruscha , the exhibition screens Wegman’s light-hearted videos.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Wegman made videos that were funny, and short—vignettes that lasted sometimes no more than several seconds. In one, we see Wegman from the neck down sitting in a chair, contorting his stomach to look as if it's singing. In another, we see his dog, Man Ray, sleeping under a blanket with an alarm clock resting on his back. When the alarm finally goes off after about 60 seconds of anticipation, Man Ray jolts into wakefulness, only to return back to sleep as if he deciding to hit the snooze button.

Artspace’s Loney Abrams visited Wegman—and his dogs Flo and Topper—in the artist’s residence and studio in Manhattan. Below is their conversation, in which they discuss Wegman's video works on view at The Met, the importance of finding an audience, and the unusual, awe-inspiring personality of his first dog, Man Ray.

You have a show up at The Metropolitan Museum of Art right now called “William Wegman and California Conceptualism,” which contextualizes you as a conceptual artist. To me, conceptual art is one of the most difficult artistic movements for the general public to understand and appreciate. At the same time, the work you’re most known for, is incredibly accessible and loved by a very wide audience. I mean, I grew up watching your dogs on Sesame Street . So, coming from this show at The Met, I’m wondering how you reconcile these seemingly polarized contexts.

I think just by understanding that they took place over a real long period of time. When first I started out as a 20-year-old California Conceptualist, I wasn't really anticipating becoming so popular, having my work on Johnny Carson or Saturday Night Live or any of those things. I was just trying to do something that seemed like the right thing to do at the time. When I see a picture of myself with long blondish hair, I go, Oh, that's me in California. I've been an artist showing my work for over 50 years. It just sort of breaks down that way.

I get the sense that it was important to you to intentionally work in formats that were ripe for mainstream media. You’ve talked about how you were hesitant to use the Polaroid 20x24 camera because you were wedded to this idea of making photographs that were small enough to fit onto magazine pages. And your videos, for example, were short vignettes—more like ad spots than films—making them more attractive to television. Was making art for the masses in itself a conceptual gesture?

That's just the way it worked out; it wasn't really the strategy.

But you wanted to be on television and in magazines for a reason. Did you find exhibition spaces and the gallery system limiting? Did you feel like your work required an audience that was outside of the art world?

I really wanted an audience; I loved showing my work. I was always a

Mom, look at this!

-kind of person, rather than the one that just works for God or whatever, like Bach or somebody like that. So that was obviously something that was built into me. I also liked knowing what I was doing. So when I understood my own work, then someone else could get it. In the beginning I made work that I couldn't quite understand—trying to grasp symbolic logic, cybernetics, things that were strenuously intellectual. Then I went,

Ugh, I'm just not that way

. Artists right around my time were doing works with math, and numbers, and other things like that and I was too. But I guess when I got a dog a couple years later, it was like a button that then got pushed over and over again that made me something else.

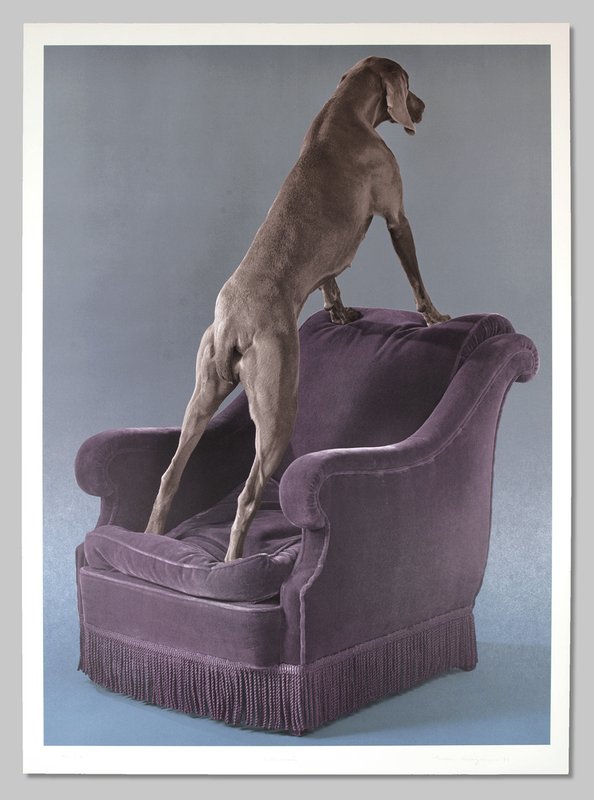

Overview (1993) is available on Artspace for $5,000 or as low as $440/month

Overview (1993) is available on Artspace for $5,000 or as low as $440/month

In your videos we start seeing Man Ray, your first dog. Do you remember making a deliberate choice to turn your pet into an actor, or did he just happen to be around while you were filming?

I got Man Ray at six weeks for my first wife Gail, who wanted a dog and I didn't. I had just started to work with video and had my own equipment, which was fun to play with so naturally he got in it. I was a little reticent at first but then I just sort of went, okay, this is okay to do once in a while. I didn't want to do it so much that I became a “dog artist.” I didn't necessarily want to make a career out of photographing a dog. But he really became so interesting both in the video and the photos. Really interesting. He was amazing in real life, too. He lived to be almost 12 and when he died I didn't get another dog for four years. So I thought that his life was this perfect bracket for that body of work.

What was so interesting about him to you?

Just the way his mind was so peculiar. And he was so into what I was doing. He also had ways of developing what I was doing. He came up with ideas all the time. I was working with photo chemicals, using cones to pour things. And he just decided that cones were interesting. So he rushed around and he found a coffee maker cone, he went into my darkroom and got cones out of there, and so on. He just had this mind. I remember when I was driving he'd try to figure out what I was doing. He'd look at my foot, and then at my hands, and then at me; he was really working, really trying to figure out why that was happening. He was unlike any other dog I've had since, or have ever met. He was pretty remarkable. He was a whole nother level of dog. He was very special and everyone knew it too.

More muse than model.

He was really wired differently.

I want to talk a little bit more about your early videos. They’re really funny, and strange, and I think they show your personality and your approach to art-making in a way that your still photographs maybe don’t. What was going through your mind when you made those vignettes?

I was using a table model of the Portapak set-up with a recorder, a monitor, and a camera on a tripod. I would set the camera so it would see me but I would look at myself in the monitor. It became like self-hypnosis in a way. I would just get lost in this image that was me, slightly off. I'd dangle something in front of the camera, look at it through the monitor, and then I'd think of what to do. I never really scripted anything. With some of the later reels I started to write some things down, but most videos just began with me talking into the camera or moving the dog around or whatever.

What was the editing process like?

I'd start the camera, run in, film it, and later edit. Editing was more like weeding the takes that were good, and then putting them all together on a reel at the end of the year. Each year had its own reel.

Seeing the videos in 2018, I couldn’t help but compare them to Vine, Snapchat, and Instagram stories and videos. They’re similar in that they’re very short (Vine was limited to six seconds; Instagrams now allows 60 seconds), and they’re often made with the front facing camera on a phone—so users can film themselves, while looking at themselves—which I know was how you worked as well. Vine especially was known for inspiring some very goofy and experimental content.

Yeah. I happened upon the video stuff when it just became available. Even though it wasn't portable by today’s standards, it was in the 1960s. The average person didn't have home video in their house. You'd go to the TV station to do a 16 mm or Super 8 film. I happened to find my video set-up at the art department at the University of Wisconsin. The artist who was using it there got it from the sports department or the medical school. So, it was just something that started come out and come available. Then it just blossomed and all these different schools of people working with video began to develop—an electronic group of people, or documentary Portapak people, or artists, or whatever.

Do you use Instagram or Snapchat?

I don't even know how to get on it. I've heard about it obviously, but I don't know anything about it. But what I was doing was really in advance of that, I suppose. I mean, you're not the first person to think of that analogy.

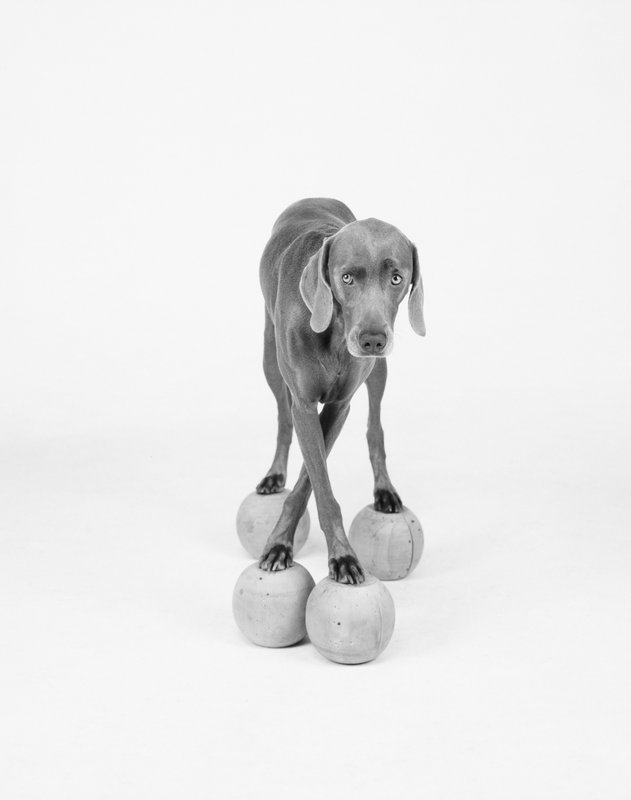

Cross Training

, 2005 is available on Artspace for $1,000 or as low as $88/month

Cross Training

, 2005 is available on Artspace for $1,000 or as low as $88/month

The Polaroid 20x24 was another example of a technology that you adapted early on.

There were five of those in 1975 in Cambridge, Massachusetts and they invited artists to come to Cambridge to use it. Then they moved the studio to New York and I would rent it every once and a while. So I used that camera till 2007 when they stopped making film.

Polaroid went out of business so you can't return to that format. But do you think you’ll ever return to video? Do you miss it?

I just made a video this year that was very different from my earlier ones. It’s not something that I'd do every day. Part of it is, I have kids who are 23 and 20. When they were young I became like a live video artist because I was always performing for them, doing crazy things. The creative impulse would lead to... it was really about trying to communicate and make someone laugh, or be astounded, or be baffled. That was something I was able to do with my children.

I really craved an audience more than I acknowledge. I really loved being in Europe with my videos. I'd cary the deck around and have people gather around to show them. What made my work so different was that it was likable rather than frightening. The first video art is pretty off putting—like somebody pounding against the wall for a while. It's kind of gripping and cool, but my work was like a recess.

Do you think that it’s important that your older video works are shown now? The show at The Met contextualizes your work within the California Conceptualists—is it important to you that your career is seen from this perspective?

Well the show is sort of odd because I was really close to a lot of people in LA (some of them are still my best friends) that aren't in that show. And some of the people who are in the show I knew hardly at all. But it's true that the reason I moved to LA was Al Ruppersburg. I liked his work.

Who were some of the artists you were close with?

David Deutsch , a personal friend of mine and a really great artist. Pat Hogan, a paraplegic artist, who couldn't walk or talk even. He was a very close friend of mine; we'd play chess together and I was the only person who knew when he was laughing. I knew all the Venice artists like Laddie Dill, Tom Wudl, Jim Ganzer, all of those people. I knew Jack Goldstein —my first show was a two-person show at Pomona College with Jack and myself. Other video artists like Wolfgang Stoerchle and a lot of people at Cal Arts, Nam June Paik and so forth. I knew Ruscha and Nauman , lots of people. But I really liked Ruscha, he was really nice to me; bought some of my work; supported me for a year. I really didn't feel that I was like anybody by the time I got going—I was photo/video but I wasn't really like other photo/video artists.

What made you decide to move to LA?

I was going to move to New York or LA—those were the only two choices in my mind. So, I moved to LA since there seemed to be something going on there, and as soon as I stepped foot in it, I was an LA artist even though I had all of this work from Wisconsin and maybe some from Boston too, I don't know. But it seemed to suit me. When I moved to New York in ‘73 I had a really hard time because I tried to compete with New York artists and tried to be more serious or whatever. I had a bit of a blow here. It could have just been getting caught up in the lifestyle of New York, rather than LA, which seemed to suit me better at the time. When I realized things weren’t working out in New York, I couldn't really go back to LA. I gave my LA studio to John Baldessari who was there for many years until about six months ago.

In LA I was able to make black-and-white videos in a studio with a skylight. It was really lovely and easy and comfortable. When I moved to New York I had to figure out lighting, I had uglier spaces, it was just... oh, god. And then a friend of mine ended up giving me a studio in East Hampton in the country and I worked there much better. I did some good pieces in East Hampton. I did nothing good in New york for a really long time. I lived on 27th Street and 7th Avenue. So grim. My dog was so pissed off not to be a block from the beach. But in New York I suddenly had representation, a gallery, I was showing in Europe, I was doing all these things. In LA, nobody would show my work because I wasn't a New York artist. I was in a lot of group shows but I had no gallery support, I couldn't get a teaching job, I was just kind of a character with this cool dog living on food stamps. Then, as I said before, as soon as I stepped in LA I was an LA artist, as soon as I stepped in New York I had a gallery and was showing in Europe. Timing: I guess that’s what that is.

Topper (2015) is available on Artspace for $8,000 or as low as $704/month

Topper (2015) is available on Artspace for $8,000 or as low as $704/month

Do you think that it’s important that art goes outside of the art world and reach the general public?

I don't think so. But at the time I did think it was a strategy. If you read about the ‘60s and what people were trying to do—in terms of being anti-establishment and finding radical departures from the conventional ways of seeing things—it makes perfect sense. I was talking to Annie Leibovitz recently about how I loved getting in magazines and things like that, and she wanted to be in museums, she wanted the wall. She didn't have the wall, I had the wall and she had the print. I love seeing my work on a postcard or an ad or some place; it's really cool. Once someone loaned me their country home in New Hampshire. I went up there and sat on the ouch with my dog and turned on the TV. And I was on the TV with my dog! It was a PBS piece. And I couldn't tell anyone because no one was there. I said, Man Ray! That's us!

I think there are a lot of artists who do feel like the gallery and exhibition space is limiting and they try to get outside of the white cube and access a broader audience. And then there are other artists who feel like anything that isn't contextualized in the white cube is not “capital A” art, or means that they’re selling out in some way. I think at their root, both approaches are trying to get at the same thing maybe, some feeling of authenticity, even though the strategies are completely different. It seems like you’ve managed to do a bit of both successfully.

Thank you. [laughs]