It’s been almost a decade since Fred Tomaselli stopped using drugs—that is, stopped encasing actual hallucinogen and stimulant pills in his dizzying, large-scale paintings. Today he's looking for other, less expected ways of transporting the viewer to mystical realities.

On a May afternoon in his cavernous studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn, Tomaselli pulled out long drawers containing hundreds of cutouts: butterfly wings, fig leaves, human mouths. The Lilliputian-sized pictures sourced from field-guides and celebrity magazines are arranged here like a natural history collection by genus, species, size, and color. (Aside from being a product of 1970s California drug culture, Tomaselli is something of a naturalist.) His collaged works, which look like psychedelic landscapes and repositories of our overloaded visual culture, tend to usher in transcendent, koan-like subject matter with a scope much larger than the monadic self.

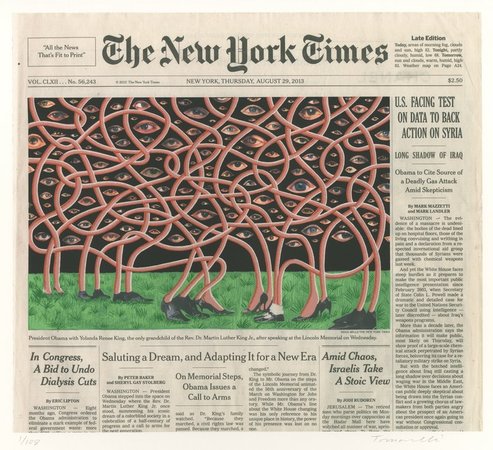

Tomaselli's latest show, closing Saturday at James Cohan Gallery in New York, underscores the social and political components of his art, particularly in his recent New York Times works. In the new series, he collages over the photographs of the front-page stories: above a tornado-razed Midwestern town looms a funnel-like cloud made of eyeballs (reinterpreting the eye of the storm?); an exploding bomb in Afghanistan transforms into hallucinogenic Ben-Day dots; Vladimir Putin is rendered as a naked woman accompanied by clothed cronies.

On a recent studio visit, Tomaselli talked to Artspace about why he began artfully editing the Times 9 years ago, and the inherent ambiguity of good political art.

Edited from an interview with Fred Tomaselli

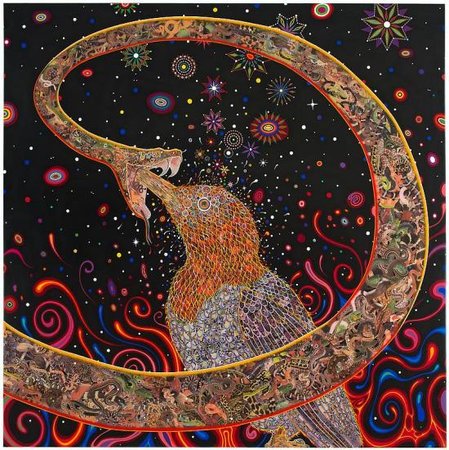

The nature prints in the new show are very Freudian. Take the bird jamming her beak into the snake’s open mouth, much like a mom bird would into a baby bird’s with a mouthful of guts. But it is also sort of sexual—the penetration—and Darwinian, in that they are trying to devour or attack one another. It's the same sort of social Darwinism that I saw on the front pages of the Times . People are doing the same fucking, eating, and killing. Those corollaries just started drifting and migrating across the works.

Every morning, I get the Times and see what's on the front page. I used to scrutinize it for the news. Now, I scrutinize it for the news and for what it might deliver to me as an artist. I’m a collagist, so I’m really interested in this idea of working with collectivist culture, here, the high mind of humanity. In my collages, I use all these images that are made by others. They come through my hands and they end up being something else. You could call me the conductor of these images.

There's something similar about how newspapers operate, with their editors, fact-checkers, photographers, and writers all coming together to spotlight certain things and omit others. They try to present themselves as objective entities, but they are anything but that. I love the idea that in my work I’m just another subjective voice in this subjective world of the news. I become another editor, imposing my editorial acumen.

And while I'm an Occupy Wall Street-style progressive guy, the underlying politics of the works are more like Joan Mir ó ’s when he was doing the constellation drawings during World War II. He made incredibly cosmic, beautiful things at the height of the war, when he was moving around and the Nazis were fucking everything up. And in a funny way, even though his work doesn’t propose to be political, it seems to me to be inherently political, in so far as it insists on art and culture in a time of carnage. I’m sort of saying the same thing with my work. My drawings on the front page acknowledge the horror of the world, bracketing these images.

There are certain ones that are explicit, like maybe when I made Putin into a naked lady. I’m poking fun, and engaging in political satire. But for the most part, the stuff I do to the

Times

is weirder than that—and it’s harder to really make heads or tails of what I was “trying to say.” And so I like to think it’s ambiguous.

The tropes that I use in my work are drawn from the objects and psychoactive material and media floating around me. I listen to a lot of NPR in the studio, for instance, and occasionally, to get the other side of things, to right wing talk radio, which freaks everybody out. But I like to know what the opposition is saying. All of that stuff enters my brain and is part of the fluidity of my mind and the conversation that goes on in the studio. I almost think of the studio as a little paradise I go into and make art, that is punctured repeatedly throughout the day by news from the outside: the Ukrainian civil war, the Haitian earthquake, the nuclear reactors melting down, the shooting in Colorado, just one thing after another.

But there's another side to that. The news is a place that people go to in order to escape. It’s another world. In some respects, it becomes peoples’ whole world. Like a shut-in who is only reading about crime in the streets all the time and becomes increasingly paranoid to the point where they won’t leave their house anymore. It affects their waking reality. As an artist, I’m interested in all these places that we lose ourselves, whether its cinema, books, theater, the Internet, plastic surgery—there are all kinds of ways we mutate ourselves and mutate reality.