With the Met Breuer’s opening featuring a decidedly net-inflected mixture of celebrated and unknown artists and the ongoing surge of “new-old” artworks in recent exhibitions and art fairs, it seems that the art world is experiencing a moment of reevaluation, looking back on unsung characters with fresh eyes. Whether this shift is prompted more by an art-historical interest in enriching the archive or a market-driven desire for a new source of product is a discussion for another time—either way, the result is a new appreciation for semi-forgotten greats that pushes them back into the contemporary discussion, a boon for engaged art viewers on the search for buried treasure. One such re-emerging artist is the Icelandic painter Erró, currently the subject of a solo show at Galerie Perrotin (on view through April 23) that spectacularly reacquaints the New York art audience to this early adept of Pop Artappropriation.

Although he’s celebrated in his native Iceland as one of the country's most famous living painters, the 83-year-old artist remains little known in the rest of the world despite his half-century career. His reputation (and perhaps some of his obscurity) stem from his dogged adherence to his technique of painted collage, in which he collects images from comics, advertisements, propaganda, and the like, arranges them as paper collages, then projects and paints the compositions onto canvas. He’s hardly changed this method since he first began experimenting with it in the mid ‘60s—for the past 40 or so years, it has been his sole approach to painting.

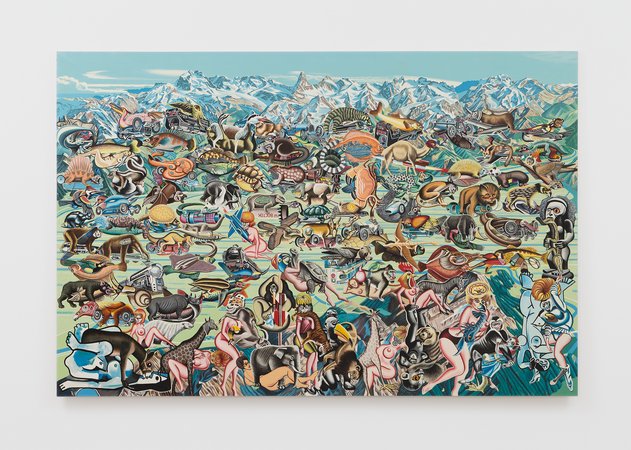

Lovescape, 1973-1974

Lovescape, 1973-1974

As a young man, Erró (then known by his birth name, Guðmundur Guðmundsson) traveled around Europe studying art, from classical painting and restoration in Oslo and Florence to a two-year stint in Ravenna exploring the art of mosaic; the influence of these experiences is evident in his works, which combine the compositional rigor of the Old Masters with the methodical process of mosaic construction. In 1958, he moved on to Paris, still the center for the European avant-garde. Free from the relative confinement of art school and exposed to the strange excesses of artists like André Breton and Max Ernst, Erró began his formal experiments, creating (non-collaged) paintings like Sensibilisateur por 23 personnes (1961) that seem perfectly at home among these Surrealist contemporaries.

Sensibilisateur pour 23 personnes, 1961

Sensibilisateur pour 23 personnes, 1961

As the zeitgeist moved increasingly towards abstraction, however, Erró began to feel out of place in Paris. Recalling that time, the painter told Artspace: “Everything was abstract. There was nothing I could do as a figurative painter. Somebody sent me to see Kahnweiler, who Picasso’s dealer at the time. I brought five or six paintings by hand with me on the metro and was put in a room to wait for him. He came in and flipped completely, saying ‘This is horrible, Nordic painting, like Edvard Munch. Horrible painter! Horrible painter!’ And he rushed out of the room.”

In response, Erró and a handful of his friends began agitating for a new kind of painting, one that preserved the best of the classical tradition he loved while still engaging with the aesthetic and political revolutions of the day. These concerns coalesced into a group of international artists including Valerio Adami, Peter Stämpfli, Herve Telemaque, Eduardo Arroyo, Peter Klassen, and Jan Voss, all working under the banner of Narrative Figuration in an attempt to rescue art from what they saw as its headier pretensions in favor of a socially and politically instructive form that remained visually pleasing.

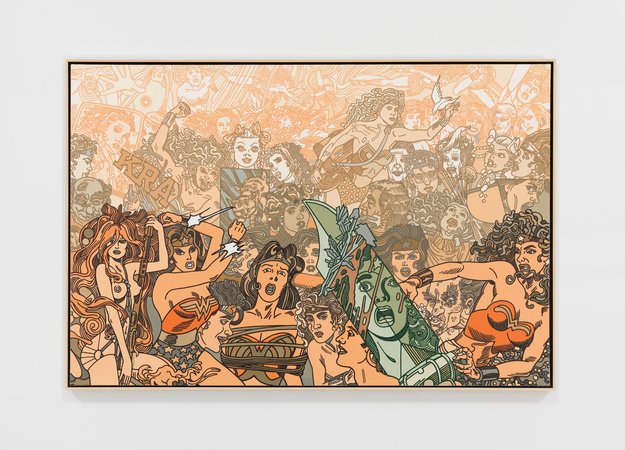

Wonderwoman scape, 1992

Wonderwoman scape, 1992

After gaining some attention showing at the annual May Salon, the painters eventually mounted an exhibition in the shop of an importer of Persian rugs. “The walls were all covered with carpets,” he says, “so we just hung the paintings on top. Then we had a big stroke of luck. Daniel Cordier’s ‘Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme’ of 1959 was right next door. The show was a big scandal because at the opening they had a naked woman covered only in food, so that people ate from her until she was completely naked. Hundreds of people came, and many people mistook the doors to the exhibitions. They went into my show by mistake—all the luck! That was really the beginning.”

Soon, however, Erró began to yearn for new stimuli, something he found readily in New York City during his first 1964 trip. Greatly impressed by both the artistic ferment as well as the openness and camaraderie of artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jonas Mekas, and others who created a congenial atmosphere so different from the cliquish circles of Paris. Decades later, he fondly recalls those heady early days in New York: “There was a party every two nights. All the doors were open, and people were so friendly, so marvelous. Nobody had money. We lived on a few hundred dollars a month—it was unbelievable. Life was difficult for many people, but we all survived. There was no competition, really—it was $200 to $300 for a piece of Pop Art.”

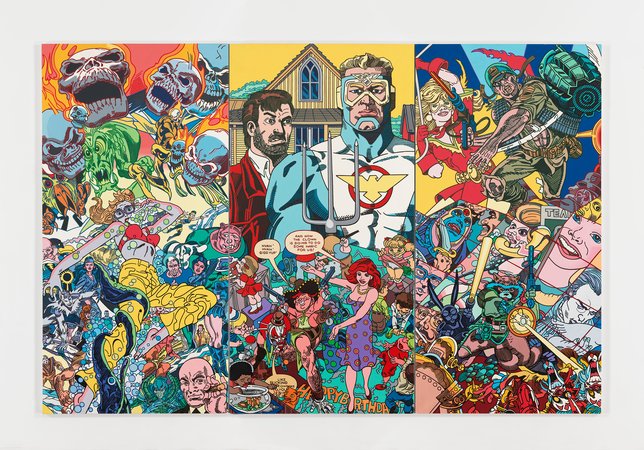

Good Morning America, 1992

Good Morning America, 1992

His time in the Big Apple wasn’t all fun and games, of course. Erró quickly began exploring new ways to expand the auspices of his Narrative Figuration. It was here that the Icelandic painter caught his first glimpses of the American-style consumerism that was about to begin its march towards global domination; sensing that a sea change was afoot, Erró began gathering the materials that would soon become the basis for the practice we see today.

It’s easy to compare Erró’s concerns at this time to those of his friends Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein, whose treatments to consumer goods and popular media (especially in the form of comics) are celebrated as shining examples of early Pop Art. Erró, however, took these conceptual gestures and ran wild with them, extending their interest in throwaway consumer culture to create imagery more akin to the Old Masters he studied as a young man. “My favorite artists are Rubens and Tintoretto because of their fabulous sense of composition and atmosphere,” he says. “I appreciate American Pop Art mostly because of the aesthetic beauty of working with only a few images—one hand, one foot, one face. Like in a supermarket, everything became very bright and visible from far away.” It’s Erró’s effort to meld these seemingly contradictory impulses that led him to renounce sui generis imagery in favor of prefabricated figures ripe for reinterpretation.

Foosdscape, 1964

Foosdscape, 1964

A prime example is his Foodscape from 1964, his first foray into the territory that would come to represent the brunt of his career. Here, hundreds of images from the packaged foodstuffs of American supermarkets (a phenomenon that had yet to disseminate in European cities) are carefully arranged into a kind of landscape populated by products. Unlike Warhol and Lichtenstein, simple reproduction was not enough—the images he uses are more akin to the individual tiles of the Byzantine mosaics he helped to restore as a student in Ravenna, component parts of a greater and obsessively rendered whole. His “-scapes” of subjects ranging from Wonder Woman (a perennial favorite) to copulating human-animal-machine hybrids have since become some of his best-known works.

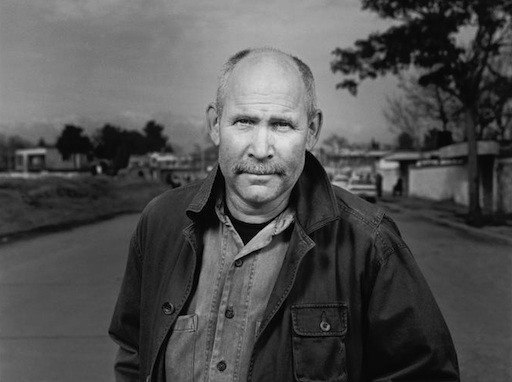

Trio Pepe, 2011

Trio Pepe, 2011

It’s notable that the process behind painted collage borrows heavily from the subconscious-mining approach of his Surrealist pals; the elder painter says the act of selecting, arranging, and painting his imagery is “like a dream” and compares it to automatic writing or drawing à la André Masson. To enable the greatest possible range for this free-form tactic, Erró maintains a massive collection of cuttings, organized by subject matter and pulled from print material from around the world. This magpie habit means that his paintings often contain diverse references, including everything from Cubist figures and R. Crumb sex hounds to Maoist propaganda and imagery of contemporary pop culture figures. The results, of course, are generally as surreal as the techniques that created them, albeit operating in a visual idiom (the clean lines of comic books) wholly distinct from Dalí and company.

Erró maintains that he is largely ignorant of his borrowed images’ backstories; when asked about his decision to include the rapper Snoop Dogg into one of the paintings on view at Perrotin, the artist in turn asked the crowd of listeners, “Who is this man?” explaining that he chose the photo in question because of its prominent hands. That said, one gets the sense when talking to Erró that he’s withholding more than he says, preferring to let would-be interpreters struggle to their own conclusions about the rationale behind the pieces. This is perhaps where the “narrative” aspect of his Narrative Figuration comes into play—much like good jokes or engaging anecdotes, overwrought explanations tend to detract from the story at hand. Even when working with overtly political source material, the artist appears to prefer that you develop your own critiques.

Dogman, 2012

Dogman, 2012

Erró is similarly cagey when it comes to nailing down where exactly he falls in the movements that have come to define 20th-century art history, except when he’s reasserting his allegiance to Narrative Figuration. A description he does appreciate, however, is from the late philosopher of art Arthur Danto, who wrote in a 1999 essay that “[Erró] has succeeded, all by himself, in bringing Pop Art into its flamboyant baroque.” Asked what he thinks about the characterization in 2016, the artist is unequivocal: “I thought it was just perfect. I love the baroque—the bigness, the madness.” Looking at his paintings now, it’s easy to see the connection. For contemporary artists struggling to work with the daunting permission offered by appropriation, Erró’s paintings offer suggestions for how to incorporate postmodern concepts while retaining the sensorial delight of a beautiful arrangement.