MIKA TAJIMA

ELEVEN RIVINGTON

NADA

Mika Tajima is fascinated by ergonomics and the way that we are able to produce devices through industrial design that can condition our bodies both externally and internally. At NADA, the artist explored this theme in head-turning fashion, placing a full-sized candy-colored Jacuzzi shell on the wall. The Jacuzzi, it turns out, was not originally a leisure devise intended to be used as an ‘80s party fixture but was instead developed by California’s Candido Jacuzzi in 1948 as a tool to treat his son’s rheumatoid arthritis. To make her piece (available for $35,000), Tajima contacted the Jacuzzi company and requested that they make her a clear plastic version; she then turned that into a painting, spraying enamel on the surface—a technique she uses in her series of Plexi Glass paintings. Adding to the effect, the piece was displayed against the backdrop of wallpaper featuring serial depictions of a contortionist who has performed at her shows.

FLORIAN BAUDREXEL

LINN LÜHN (DUSSELDORF)

NADA

This hulking piece that seems to inhale the space around it was made by the German artist Florian Baudrexel, who specializes in collaging cheap materials into brutal yet beautiful works of art. Made from cardboard boxes that he glued and screwed together onto wood before removing the screws, leaving a scattering of holes around the surface to make visible his process, the sculpture (priced at $40,000) is unexpectedly riveting as decor—a fact noticed by the editors of T magazine, who included it on the cover of a design issue a while back. These pieces have won over Miami collectors as well, with one ending up in the Margulies collection and two others in more private collections, and they recently had an outing in Houston at Lora Reynolds Gallery. Baudrexel has several shows coming up in Europe next year, including one in Copenhagen and another one in Dusseldorf later in the year.

SARA CWYNAR

FOXY PRODUCTION (NEW YORK)

NADA

Having worked for years as a designer for the New York Times, the Canadian artist Sara Cwynar knows her way around image archives, and now that she has transitioned to making art of her own she’s putting that knowledge to exquisite use. At NADA, she had a series of photographs ($6,000 apiece), each following the same process: she fixes on a theme (Bridget Bardot, the Acropolis, palm trees, Mondrian) and gathers a collection of images, rephotographs them with her finger in the shot to indicate scale, and then cuts them out and lays them on felt before photographing them all for the final composition. The issue of scale is key—the finger adds a literally indexical element—and the multiple plays on photography recall the work of Anne Collier and Elad Lassry. Foxy Production discovered the artist when they included her in a group show and later included her in her first solo show there this past spring, and despite her career already taking off, she decided earlier this year to go to Yale, where she’s currently getting an MFA.

GRAHAM COLLINS

THE JOURNAL (BROOKLYN)

NADA

Wasn’t Graham Collins on last year’s artists-to-watch list? Yes indeed he was, but you could be forgiven for thinking that this was the work of a completely different—and even more compelling—artist. Whereas last year Collins presented pieces of dyed burlap behind tinted glass (a series that stirred up an enormous waiting list at the fair), this year he had a series of delicate bronze sculptures that seemed both ancient and modern. Until, that is, you looked closer, and saw that they were made from latticeworks of, alternately, cast potato chips, Fritos, Doritos, or toothbrushes. Made over the summer while at a residency on the Greek island of Hydra, where he began experimenting with the material, the pieces recalled Twombly’s exquisite casts of studio detritus, but with a more meme-ready spin. The sculptures were priced at between $8,000 and $18,000, and while a couple had reserves on the second day of NADA, there certainly wasn’t the same feeding frenzy there was last year—but, the market notwithstanding, the works make his second solo show at the Journal next fall even more of an event to look forward to.

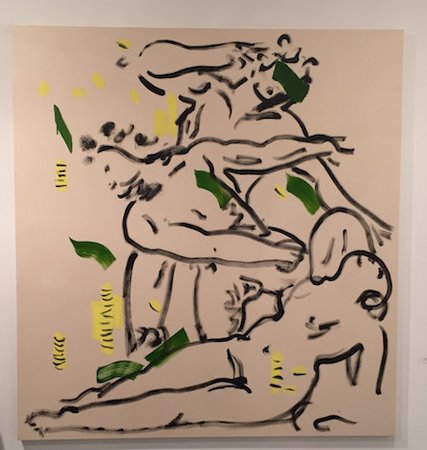

JACK MCCONVILLE

IBID PROJECTS (LONDON, LOS ANGELES)

NADA

Capital and the expression of wealth is the subject of the Glasgow-based Jack McConville’s entertaining paintings, which he lays down in a loose, comic, and strikingly assured style—each dollar bill is a single brush stroke, each stack of coins is a dash of gold. McConville is inspired by the ways that money and social status have been depicted throughout Western art, from the opulent signifiers of Renaissance art onward, and here he shows a trio of classicizing figures in what appears to be a postcoital money-clutch. Painted in oil on unprimed canvas, the paintings on view at NADA ranged from $6,500 to $14,000 (one sold to a well-known art foundation in Beijing), and the artist has a current solo show at IBID’s L.A. space.

PETER DREHER

KOENIG & CLINTON (NEW YORK)

UNTITLED

In 1974, after six months of meditating on a topic, the German artist Peter Dreher began painting a single drinking glass on a tabletop in his Wittnam studio each day, keeping the window framed in the lower left of the glass and maintaining the same muted palette of whites and greys. He titled the series “Day by Day Good Day” after a Buddhist poem, and alternated between day and night—with the changing light quality the only real variable—writing a number at the top to indicate its sequence in the series. Dreher, who is 73 years old, has now been painting this glass for 40 years in an epic undertaking that has been compared to a marriage of On Karawa’s seriality with the sensitive paint handling of Morandi. But while he has a modest following in Germany, where he has worked in an art-school teaching painting to such students as Anselm Kiefer and Wolfgang Laib, he hadn’t had a show in the United States in 15 years until Koenig & Clinton gave him a solo in April. Now something of a slow-burn sensation, Dreher is receiving newfound attention for his glass paintings ($7,000 apiece), as well as his larger geometric abstractions, several of which were featured at Untitled as well ($25,000-$75,000, reserved for institutions).

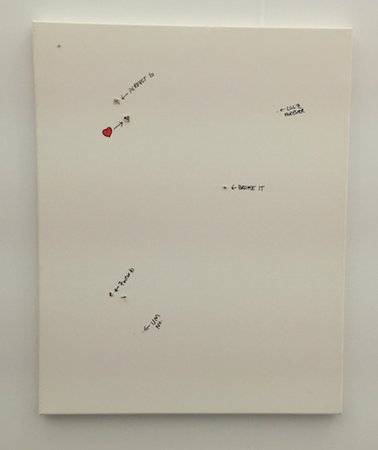

ADDIE WAGENKNECHT

BITFORMS

UNTITLED

Drawn to issues of surveillance and open-source technology, the Austria-based artist Addie Wagenknecht probes the spookier reaches of the digital era in her work—terrain she is especially well equipped to explore given the fact that she has a computer science degree from NYU’s elite Interactive Telecommunications Program. To make one of her pieces at bitforms’s Untitled booth, the artist downloaded files for the hugely controversial Liberator gun—a 3-D-printed handgun that can fire real bullets—and created five of them, shooting bullets into a stretched canvas; because the technology isn’t very consistent and the gun misfires frequently, not all of the bullets penetrated the fabric, and Wagenknecht indicated their success by writing on the canvas (“Perfect 10” and a heart shape for deadly shots, “Um. No.” and “LOLZ Forever” for the ones that bounced off). The “painting” was on offer for $4,000, while a blinged-out modem was $2,000 and a gunpowder painting made with a drone was $3,500.

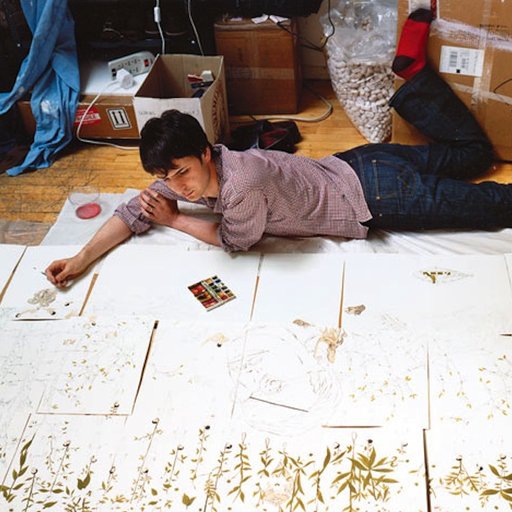

JON RAFMAN

ZACH FEUER (NEW YORK)

NADA

Jon Rafman has made a name for himself with works that mine the Post-Internet seams of digital technology, swiping images from Google Street View, printing dysmorphic sculptures, and tapping into the aesthetics and disquieting possibilities of video games. At NADA, however, he ventured into fresh terrain with the first piece he has created entirely from scratch—in other words, not found online—and it feels like something pointing a heady new direction in art. Call it Post-Reality.

Circulating through the fair via fervent word of mouth, Rafman’s piece was not in the aisles but in room 1111 of the Deauville Beach Resort, where visitors were invited to walk through to the balcony in the back—with a plunging view of the sea fanning out beyond a relatively low railing—and handed an Oculus Rift virtual-reality visor, then told to put their hands on the window into the room and wait. After a moment of darkness, a virtual version of the inside of the room pops into view, rendered in the grainy style of early ‘90s video games; a figure seems to be lying in the bed, concealed by the blankets, and de Palma’s Scarface plays on the TV. The viewer is then prompted to look around the balcony, and the ocean view is also rendered in video game style, with pixellated grey seagulls winging through the air.

Suddenly, things get weird. The landscape seems to shatter, with jagged shards of sky flying out into white space and giant grey forms—exploded seagulls?—hovering menacingly overhead. After a moment of total disorientation, the viewer is instructed to remove the visor so as not to get nauseous.

Called Junior Suite, the piece was developed by Rafman alongside the programmer and artist Sterling Crispin, and the effect—at least for newcomers to the technology—is jaw-dropping, particularly due to the disconnect between being in a virtual world while also standing in reality so close to a precipice. The work is clearly at an early stage, but Rafman sees the project as a long-term investment in the medium, which is continually evolving and advancing in the hands of developers. Next year he’ll have solo shows at the Zabludowicz Collection and the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, and he says to expect more work of this kind there.