Art Basel—in its Swiss, Hong Kong, and Miami Beach incarnations—is usually thought of as an art fair for high rollers, filled with pricey works by established, blue-chip artists. But, in and among the labyrinthine maze of booths, some younger (but no less impressive) artists and their galleries have staked out the space to strut their stuff. Here, we’ve taken a close look at seven of the most exciting up-and-comers from this year's Art Basel Miami Beach, all born between 1980 and 1990 and thus representatives of the new generation of artists that is already in the process of taking over the art world. Commit these names to memory—it won’t be the last time you hear them.

AAAJIAO b. 1984

Leo Xu, Shanghai

GFW List, 2016. $20,000

GFW List, 2016. $20,000

A self-described “new media artist, avid blogger, and free thinker,” the artist known as AAAJIAO (born Xu Wenkai) takes up the aging banner of Net Art to create expansive and somewhat creepy pieces that reflect the strange realities of our overnetworked 21st-century existence. GFW List takes on China’s infamous censorship of the internet directly, printing out reams of paper containing the information from banned websites that the artist saved just before the sites were taken offline. (The works title refers to the so-called “Great Fire Wall.”)

The sculpture-cum-printer, meanwhile, is itself modeled after the mysterious monolith from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which promised to bring humanity to ever-greater states of advancement. If you’re looking for some juicy counterrevolutionary reading material, however, this isn’t the place—the words are still encrypted, meaning you’d need a special cypher to decode these state secrets (or whatever they happen to be).

The piece is shown alongside Email Trek, an ongoing project that’s currently also on view as part of the Jewish Museum’s show “Take Me, (I’m Yours),” made possible by a special program designed to email every person in the United States a special message from the artist. After pulling names from a recent census, the program tries various combinations (john.doe@gmail, john-doe@yahoo, jdoe@hotmail, etc.) in an attempt to reach out at random to the American populace. The piece ends when all of the messages bounce back—either because the medium of email has become obsolete, or because there is no one left alive to receive them. Kubrick would be proud.

KELLY AKASHI b. 1983

Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

Eat Me, 2016. $20,000. Image courtesy of the artist and Ghebaly Gallery, photo by Jeff McLane

Eat Me, 2016. $20,000. Image courtesy of the artist and Ghebaly Gallery, photo by Jeff McLane

It’s not what you think! These shapes are based off of dried shallots that the L.A.-based sculptor Kelly Akashi leaves out to desiccate in her studio, creating warped and, yes, erotically evocative forms that she then 3D-scans and casts in a mixture of silicone rubber, resin, glass, and fabric. These delicate works are then suspending on ropes anchored by cast-bronze hands, creating hanging sculptures that can be adapted to fit any space by tying knots in the ropes.

This kind of flexibility is important for a newly in-demand artist like Akashi, who at the moment in the midst of a boom time; these works were originally commissioned by the Hammer Museum as part of their “Made in L.A.” biennial, where they hung suspended high in an atrium. In the confines of the gallery’s booth, however, the intricacies of the artist’s craft can be better appreciated at eye-level. If you simply can’t get enough Akashi, be sure to stop by Ghebaly’s Los Angeles space before the end of the year—the young artist’s first L.A. solo show is currently on view.

ANNA K.E. b. 1986 & FLORIAN MEISENBERG b. 1980

Simone Subal, New York

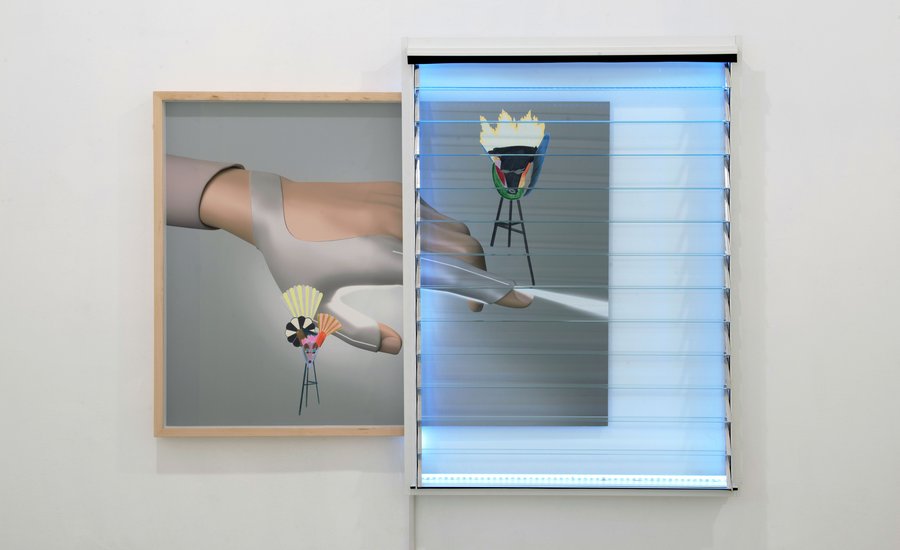

To be titled, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal

To be titled, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal

Art-fair booths don’t necessarily need to be curated or consistent to sell their wares, which makes finding one that’s both a special treat. In their Nova booth, the New York gallery Simone Subal is showcasing the the integrated work of two exciting up-and-comers, Anna K.E. from Tbilisi, Georgia, and Florian Meisenberg from Berlin. The two artists are a couple as well as collaborators—they’ve shared a studio and an apartment in New York since they moved to the city in 2010, an intimate work/live situation that they say some of their friends are still struggling to wrap their heads around. Contrary to these calls for privacy, the two are proud to note that they’ve never seen the need to install a wall in their studio, preferring instead to let their personal practices bleed into on another while maintaining immediately distinguishable approaches.

Meisenberg uses painting as a way of talking about digital bodies; human forms slip in and out of view in his large and sometimes shaped canvases, allowing other shapes, colors, and patterns to take over, not unlike the experience of multi-window internet browsing. K.E. takes the metaphor even further, rendering a 3D cyborg-esque hand alongside digital scans of earlier drawings before putting them behind two different kinds of “windows”—the rarefied artists’ frame, denoting authority and preservation, and a slotted glass window, suggesting the voyeuristic act of peering into a stranger’s home.

To top it off, the booth also features a collaborative video piece by the pair, in which Meisenberg tracking K.E. with a digital camera while she peers intently at a livestream of the same, enabling her to move in response to his camera, which in turn forces him to adapt to her movements in an evocative reversal of the usual relationship between an artist and the object of their gaze.

CHADWICK RANTANEN b. 1981

Standard (Oslo), Oslo, and Essex St., New York

Spinning Globes (Black, Beige, Blue) [Monarch], 2016

Spinning Globes (Black, Beige, Blue) [Monarch], 2016

A good sign of a young artist’s ascendency is being shown in multiple booths at the same art fair—meaning if you’re not already aware of Chadwick Rantanen’s mouthful of a name, you should be. (If that doesn’t convince you, maybe his solo show at Secession this September, his first museum turn, will.) In his offerings at both Standard (Oslo) and Essex St., the Wisconsin-born artist showcases an affinity for the hidden power of batteries as well as the things they power as he mangles and reconfigures kitschy consumer objects for his own aesthetic ends.

Standard (Oslo)’s booth features several of his recent globe sculptures, first shown at the gallery this May. Rantanen has invented handmade adapters to allow AAA batteries to fit into AA slots, which he then decorates to becomes bees or butterflies whose wings slowly flap as the globes they power spin in place. His offerings at Essex St. take this impulse even further as he remixes mechanical turkey decoys used for hunting to create near-abstract hanging sculptures that slowly move their wings along with their battery-insect counterparts—a grisly meditation on American manufacturing, hunting culture, and bloodlust.

His gallerist remarks that the people who most appreciate Rantanen’s work are often handlers and other blue-collar art workers, who appreciate his status as a maker as well as an artist.

KORAKRIT ARUNANONDCHAI b. 1986

Clearing, Brussels

Tree of Life (United Nations), 2016

Tree of Life (United Nations), 2016

With impressive showings at MoMA PS1 and this year’s Berlin Biennale already under his belt, it’s safe to say that the Thai multimedia artist Korakrit Arunanondchai has arrived. His work is nothing if not diverse, ranging across video, sculpture, installation, and more, but he’s perhaps best known for his grimy, vitrine-bound environments, including Tree of Life (United Nations) on view in Clearing’s booth. It’s part of a series made for the aforementioned biennale and represents what his gallerist refers to as a “4D extraction” of a story, with “all the data, plus the timeline” of a semi-defined narrative by Arunanondchai.

The result is a self-contained world, devoid of people (despite a model of the U.N. building suspended in a tree) but heavy on neon lights, mushrooms, and oily black stalactites, evoking the subterranean realms of caves as well as the more metaphorical depths of newer hidden places like the Deep Web. His gallerist suggests that this concern for packaged, visual narrative comes both from Arunanondchai’s ongoing fascination with filmic narrative as well as his appreciation for similar environments by other artists, including especially Mike Kelley’s “Kandor” series of miniature cities inspired by Superman’s home world.

SHELLY NADASHI b. 1981

Christian Andersen, Copenhagen

Though she trained as a puppeteer at Jerusalem's School of Visual Theater before receiving her MFA from the Glasgow School of Art, you’d be hard-pressed to find any marionette strings in these ceramic pieces by the globetrotting Israeli artist Shelly Nadashi. In addition to her work in clay, she continues to explore the ways that audience and artist (whether physically present or not) interact with and influence one another through her films and installations, which often blur the lines between static artwork and theatrical production through their use of papier-mâché puppets that double as sculptures and cyphers.

The works on view at Art Basel represent another trajectory in her work. Her gallerist Christian Andersen explains that she moved to Singapore nearly two years ago, where she first became exposed to the long tradition of ceramics in the port city and began, as he says, “grappling with the material.” The tiles and masks in the booth reference leaves and flowers, lightweight and almost ephemeral entities that exist in opposition to the heavy materiality of fired clay. Elements of performance are never far afield in her work, however—the masks are displayed on a table at eye-level, allowing their abstracted forms to stare directly at the viewer, puppets temporarily without their puppet master.

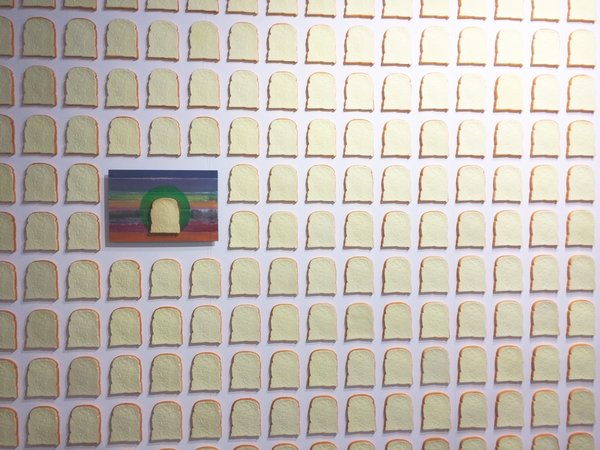

GAO LUDI b. 1990

White Space Beijing, Beijing

As one of the youngest artists at the fair, Gao Ludi has more to prove than most—and he does it with gusto. With a background in painting coupled with a willingness to experiment in other media, Ludi’s works shine with the enthusiasm and verve of an artist looking to make a name on the international stage. Like many artists of his generation, his focus is on mediating between the virtual and the physical; his chosen entry point is none other than Alice in Wonderland, a now-classic tale that’s inspired more than a few analogies to otherworldly or psychic travel over the years. His pink rabbits highlight this connection, but it’s there too in his colorful wall-filler of a painting Five Pavilions, whose tilting doors suggest paths to the alternate worlds that fascinate the artist. By far the most eye-catching work in the booth, however, is Alice, a wall’s worth of fake bread that looks, feels, and even smells almost exactly the real stuff—but isn’t.