Impresarios of the unexpected, the ironic, and the theatrically gripping, the Danish artist duo of Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset have pursued one of our era’s most ambitious creative collaborations since their chance meeting at a Copenhagen club one night in 1995. Humor and pathos intermingle fluidly in their work, such as their famous collectors’ house that spanned two pavilions at the 2009 Venice Biennale, inviting visitors to roam freely among the tastefully done-up décor only to find one of the occupants’ corpses floating in the pool out back. They are never afraid to go out on a limb, such as when they traveled into the desert outside Marfa, Texas, to plant an ersatz Prada store and see what happened.

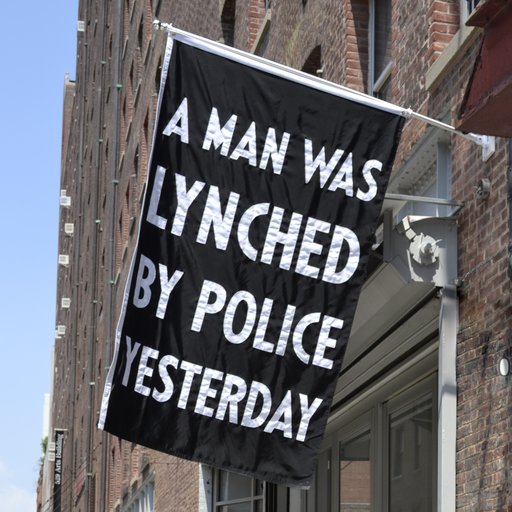

Now, a few months after they installed a gigantic swimming pool—a frequent motif of theirs—upright in Rockefeller Center, the artists are returning to New York for a new show at the Flag Art Foundation. They are also preparing for an undertaking that will carry their ambition to a new purview, as the curators of the 2017 Istanbul Biennial. To find out about the ideas and creative process behind their work, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Elmgreen & Dragset in their enormous Berlin studio, a former water-pumping station that has been converted into a laboratory for spectacles of all kinds.

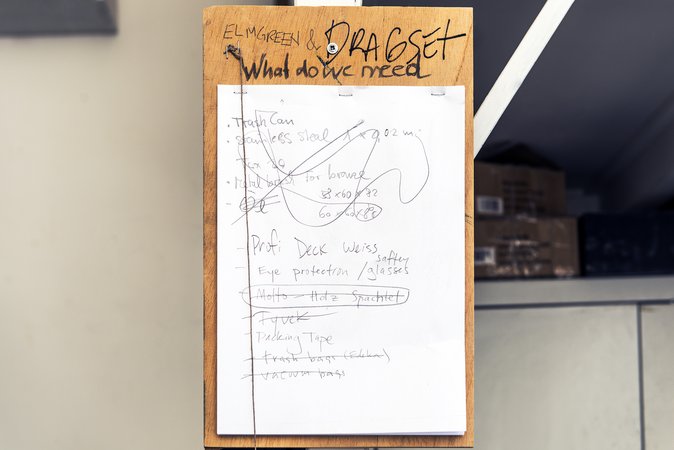

All photos of Elmgreen & Dragset's Berlin studio are by Ariel Reichman

One of the most unusual, and most exciting, elements of your work is the way it slips in and out of a wide variety of disciplines, from painting and sculpture to architecture and theater—it keeps your admirers guessing what direction you’ll take next. This is partly due to the fact that you both came to art at an angle, after training in different fields. How did you individually get drawn to art, before you even met each other?

Michael Elmgreen: It’s really based on coincidences. I never had wet, teenage dreams about becoming an agent within the art world, and I didn’t even have any real knowledge about the visual arts because I come from a family that did not go to museums and introduce me to modern art. I started writing poetry, and in a language like Danish you might as well just Xerox your poems because your books would be only published in 300 copies—the country has five million people, and that’s approximately the percentage that will buy poetry. So, I thought it was a bit ridiculous to go through the printing process and the censorships at the publishing house and whatever. Why not try to do my text experiments in a different format?

So I made text that would morph on computer monitor screens in front of people’s eyes. This was back in the days when the computers were still IBM and you were very limited in what you could do, and the only place I knew of where I could possibly show it was a kunsthalle that was close to the main department store in the center of Copenhagen. So I went there and asked them if I could show my poems, since I was a poet and not an artist, but I needed a space where people could go and look at stuff. They let me do the show, and people came—but it was more people from the visual arts than people from literature.

Then, I started getting weird invitations to be in group shows that I found rather exotic. I was thrilled by the social aspect, compared to sitting alone making your poems and actually never really meeting your readers unless you had a talk or a reading somewhere, so I thought this whole setup in visual art where you’re actually quite close to the people who come and look at your art was fascinating.You would actually meet people at the opening, at least, and you could see how they reacted when they were introduced to it.

And Ingar, how did you get involved with art?

Ingar Dragset: I think I’m similar in that I didn’t know it was possible to become an artist, and I didn’t have any sense of an international art scene when I was growing up. It was a very different climate. There wasn’t any market in Scandinavia either, even by the time we met—there certainly weren’t as many galleries as there are now. There were some that showed paintings, you know, and more classical art things, but in the mid-‘90s that changed, and for us it was like a whole new world opening. Initially, I was drawn to theater because it was much more like a world of possibilities. Theater was always around, it was in schools, and of course every European city has a theater and you have amateur theater groups. So, that was how I entered it, in high school—I got specialized in theater, and I got interested in creating through that, I guess.

Were you an actor?

Dragset: Yeah, an actor, but of course, in these groups I was part of when I was young, everyone did everything—you did the acting, you did the costumes, you did the stage sets and all of that. That’s how I came to Denmark as well, to go to theater school. I was inspired by [Jacques] Lecoq, who was a French mime/physical theater guru, or, if you will, master. I was there for two years, and then Michael and I met. After that, we began making these art experiments, and with my theater background we found a way to combine the two and do some smaller durational live acts—little experiments, almost—within that undefined, young contemporary art scene. I was very open to this.

Elmgreen: There was very much a do-it-yourself kind of art scene for emerging artists in Copenhagen at that time. There were no established galleries that would show artists who were not making painting or sculptures in the classic sense of sculpture, so instead we had all these artist-run spaces where the audience for the most part consisted of the artists’ friends and students from the academy and a tiny group of other people, which was extremely helpful because you could experiment freely without any serious consequences. You could do stuff where you wouldn’t be afraid of failing, because it didn’t matter.

You certainly wouldn’t think about the commercial aspects of your art at all, which is so different from most art students today, who come out of academies and immediately need to make a decision about what gallery to work with and what their position will be in the international art market. Now they need to know about what’s going on globally to make a realistic career for themselves, and but we didn’t have any of these considerations at that time. It was a complete different time. You also would not see art positioned as a part of the more mainstream culture as you do today—art would not appear in glossy magazines and in tabloid newspapers and on television. It simply wasn’t part of the wider world in Scandinavia at that time. So it made it a very soft environment for self-development as an artist.

It’s interesting that both of you came out of very ancient forms of performance, poetry and theater. How did you wind up making objects? How did objects become your way of expressing yourselves?

Elmgreen: I feel it very much comes from experiencing the limitations of space. Space is something that you become very aware of in a performance, because you move through the space and you have to consider the audience at the same time—it’s very much about how you position yourself as a performer in relation to the audience and your surroundings so that everything speaks together. So, if you look at our early works, like the Diving Board that penetrates the window [at Copenhagen’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (1997)], which was one of our very first sculptures and the first one where we were noticed in a wider context, that was something that commented on space in a performative way, you could say. It broke the membrane between what constitutes the institution and what’s outside, and it’s also an object that invites the viewer to interact with it in a way—but because the board is literally going through the glass window, it’s impossible, of course, to interact with it. We call these kinds of works “denials,” and they refer back to our early performance pieces, and the body in relation to space.

I think that work is such a great example, because even though its just a still object, it becomes a kind of prop for a performance that takes place in the viewer’s mind—you can imagine someone climbing up on the board and diving out the window. It becomes a jumping-off point, if you’ll forgive the pun, for a kind of deliciously macabre scenario. That’s something I really enjoy about your work, that it furnishes everything you need for a storyline full of dramatic tension, and then the viewer completes the performance by imagining it. Is this idea of performativity—the notion that a lifeless object can, in its own way, perform—something that you think about? That you can leave an object alone in a room and know that when people walk in it will spring to life for them?

Elmgreen: I would say yes. I mean, we were inspired in a way by the generation just before us—like Félix González-Torres, for instance—who had added this kind of content back into the object in a reaction against the Minimalist aesthetics that were initially meant to drain the object of connotations and content. From there, of course, we took it into other social issues, so our objects speak for different kinds of issues than Félix González-Torres’s did.

When you’re creating an object, how do you think of your audience? Is it an individual? Is it a group? Are you creating a setting?

Dragset: You try to create a platform for experience, but you don’t calculate certain reactions because people are so fucking complex—you can’t really predict what will happen when you place your work somewhere. I find it very arrogant if you calculate a fixed reaction, and works that rely on very specific mechanisms are often quite unfortunate. A work of art needs to have a degree of openness so that people can have the possibility of having a certain experience, but also the possibility of having the complete opposite experience as well.

So, you hope your work to inspire lots of individual experiences—a crowd of individuals.

Dragset: And there is a narrative, of course, embedded in our works, but the installations are also there physically because they say something that is hard to convey in just your normal language. Otherwise, we could just write a book. And if it would just be referential, or if it would just be storytelling in a way that could be transferred into a written language, then it wouldn’t make sense to create it as a physical setting. So, I think that’s where poetry comes in to play—you want to create a meaning that is in between the lines, in between your ideas, in between the materials, in between all these things that the work consists of. Then all that together creates something that is new.

What is your process of working together? What is the research like? And how do you arrive at these extraordinary, spectacular images, like a swimming pool standing upright like van Gogh’s ear, as you had in Rockefeller Center, or the recreational vehicle bursting from the ground that you installed in the Milan shopping center?

Dragset: I mean, there are some things that are common for all processes, and for most of the larger projects its the architecture and the needed surroundings that plays a huge role. Now, those two projects you mentioned are different in nature, but in the case of the one at Rockefeller Plaza, it’s very much a reaction to the specificity of the space, the architecture, the busy nature of the area, the demography, the businessmen on their way to and from work, the hectic urban life. And we contrasted that environment by putting a pool there.

Elmgreen: We wanted to create a sort of alienation of that powerful plaza so that we might be able to rediscover it and see what it is. It’s already so iconic—it’s already so set and fixed and almost indicating no possibility of change. Rock Plaza is a symbol of power in many ways, and you have to think of what kind of object can actually make you rediscover this whole area of this plaza. How is it possible to see it in a new way? It was the same with the desert and the Prada Marfa.

I mean, the desert is very powerful. It’s very laid out. So, how can you experience nature in a way where it is not just picturesque verandas and cinematic landscape, but where you see it suddenly in a completely different way? By putting this alien object into it, implementing this little disease, this little strange UFO in that powerful, visually powerful, environment.

That reminds me of the Wallace Stevens poem “Anecdote of the Jar,” where just placing an empty jar in the wilderness changes the entire context.

Elmgreen: Yeah, yeah, beautiful. Exactly.

Where does the idea for a project come from? Do you go to these sites first and wait for inspiration? Or do you have an idea and then scout for the perfect setting?

Elmgreen: For the Prada Marfa it was the other way around than is usually the case. We used to work with Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Chelsea, and at the time you already saw the strong signs of complete gentrification in Chelsea and SoHo—Prada had just taken over the Guggenheim’s former project space in SoHo—so for our first project there we covered up the windows of the gallery, saying, “Opening Soon, Prada.” We didn’t have any permission from Prada to use their logo, but of course they didn’t sue us because they’re interested in art. After we did that project, immediately the idea came into our heads of putting a Prada store with its signature interior design into a completely new environment, like a desert.

At first we thought about a Prada Nevada, just because of the sound of it, but we didn’t find anyone in Nevada slightly interested in a Prada store in the middle of the desert at that time. Then we met the people from Art Production Fund who said they had connections in Marfa, so we went out there and looked for sites, and 40 minutes outside of Marfa, actually, we found a place where there was absolutely no culture—nothing but a few ranches—where we were able to get a little piece of land from a landowner and we just made it.

Now that’s become one of the great icons of the past 30 years of art. There’s even a photographer that we have on Artspace, James Evans, who has become famous for his photograph of the installation.

Dragset: There are many people who are living off of Prada Marfa—they can earn a lot of money. There are also even Magnum photographers who have been there and can sell their pictures of it $10,000 to $15,000.We haven’t really done anything about it. We ourselves were appropriating Prada, so it would be a little bit absurd to get upset about it.

Your form of dramatic, spectacular art experiences, where people need to physically go to the artwork to truly appreciate it, is so relevant at the moment—it’s something everybody is trying to bottle, in a way, now that so many people content themselves with just looking at art online or on Instagram.

Elmgreen: But it’s fun for us because it goes back to when we could be completely free experimenting in the nerdy Copenhagen art scene, where it didn’t matter if anyone saw it. Art meant something completely different at that time. The Prada Marfa is also pre-Instagram—it’s even pre-Facebook, really. I think we held the opening with four people from New York including our dealer and a few others, and then there were local ranchers who came with their cowboy hats and said, “I don’t know what this is about, but I think it’s pretty.”

Dragset: Western guys with their guitars.

Elmgreen: Yeah, they enjoyed it somewhat.

Dragset: They accepted it because we had been there before and had gotten to know a few key people who spread the world, “No, they’re ok, you can accept it.” So then it was fine.

Sounds like the best Prada opening ever.

Elmgreen: We didn’t expect that work to be one of our most well-known works at all. We were just thinking of doing it because we wanted to see it ourselves. But social media has actually made that work live on. That’s an example of a work that’s really highly prized on social media, because it’s so far away. It’s a three-hour drive from El Paso to go there, and when you get there it’s not a crowd-pleasing environment of any sort.

Dragset: Have you been to Marfa?

No, I haven’t. It’s about as foreign to me as the moon.

Dragset: I was surprised—I absolutely loved being in Marfa and being in that landscape. I grew up by fjords so I thought I would be very unhappy to be in such a landlocked area, but the variety of landscape there is amazing.

Elmgreen: It’s fantastic when you first get there. But it’s a hell of a journey.

Prada Marfa is a very crowd-pleasing artwork, but a lot of your works have thorny issues embedded in them—issues of powerlessness, and oppressive power structures. Before, you mentioned how Félix González-Torres brought content back into Minimalism with his work about the ravages of the AIDS epidemic, and you have made intensely moving work about the gay experience as well, in particular your Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism in Berlin. The memorial is a small concrete bunker with a window, and viewers who approach to peer in through the narrow window see a video of two men kissing—a sight that is meant to be something of a surprise, even a provocation. Can you talk about your intention with this piece?

Elmgreen: For us, it was very important with the memorial to show an intimate scene between two gay lovers because there’s been a lot of improvement in lawmaking for equal rights around the world, but it still doesn’t really change the homophobia that you still see when people are confronted by a passionate scene between two guys in public. You’ll still have a lot of bad reactions to that today. So, the idea was to show that the problem is not over by just governmental decisions—the problem is also: are you able to face two guys kissing without it upsetting you? Therefore we made the window very small so it would only be maximum two persons looking at it at one time, or it would just be you and the men in the film.

The shape of the memorial was of course referring to Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, because at first there had been discussions about making one memorial for all the different victim groups all together, but it turned out in a very disgraceful manner that not all of the victim groups wanted to be in the same memorial. So, we tried to use architecture to overcome that hostility the victim groups had toward each other. So, these were the main considerations when we were doing that. But it’s a special situation, doing a memorial that somehow has to function as a representation for a whole group of people. It’s almost impossible.

Originally, the idea was that the film would change every two years, with a new filmmaker contributing it each time. Has that happened?

Elmgreen: Well, to be honest, that hasn’t really worked out.

Dragset: It was a beautiful concept, because there were some voices against it being two guys kissing—then that meant the lesbian and transgender populations were not depicted. I don’t buy that argument so much because I don’t think the two guys represent two gay men, because gay men are also very, very different among themselves. I mean, you have different races, you have different ages, you have different preferences and whatever. I don’t think representation works that way. Two girls kissing would not represent lesbians—it becomes like American television when you simplify that way.

But, anyway, we were open to the concerns and said why don’t we just make a competition, or why doesn’t the government make a competition every year, and people can send in new proposals for a new movie. But bureaucracy and lack of quality submissions have made that harder to do. It would be wonderful if the government organized it so that there would be a new move, but we don’t want to go in and take charge of that because we’re just the artists who won the proposal for the memorial—we don’t own the memorial. So, they need to figure it out.

Who made the film that’s in there now?

Dragset: We did. We had a director who was helping us, but it’s definitely our film.

Elmgreen: It was shot by Robby Müller, who made Down by Law, Paris, Texas, andmany, many fantastic movies.

Dragset: Since we don’t work with video or film, we also asked Thomas Vinterberg, a Danish film director, to basically help us in the process of doing it, because we didn’t want to anybody to come afterwards and say, “They don’t know how to do video—it’s great memorial, but it’s unfortunately a terrible video.”

Elmgreen: We filmed it on the site where the actual concrete structure is sited. We managed to do it a year prior to construction because we wanted to do at that time in the year when there are no leaves in the trees and it’s a somber kind of background. And of course Tiergarten, where the memorial is, has always been a meeting place for gay guys as well.

Dragset: A gay activist group in Germany that fought for this memorial for 14 years, and it was an amazing decision by the government to accept the proposal. It’s amazing that we could finally do the work.

Is this the only time you’ve worked with video or film?

Dragset: Yeah.

I’ve read several of your past interviews where you have both talked about not being interested in biography, and not wanting to invest your own stories into your own work. But in the years since that memorial, you have made several works about the gay experience that seem autobiographical, and last year you began a new series called “Self-Portraits” where you made paintings of the museum wall labels of artworks that have particular significance to you, like Félix González-Torres and David Wojnarowicz. In addition to being obliquely autobiographical, this series also advances the engagement with conceptual painting that you began with your “Named” series of monochromes.

Elmgreen: For that series it was the actual paint from the walls of museums around the world, taken down by a restorer who put them on canvas. So, we didn’t paint it ourselves—the wall-painters in the museum had already painted them.

Dragset: But, of course it references the old monochrome paintings.

Elmgreen: It’s like when you have a fresco or a mural in a church—when you need to restore the church you take down that mural with the same technique. We found a restorer like that.

What is it about these labels and wall segments that appeal to you so much?

Elmgreen: It has very much to do with the small, overlooked elements of the art space—the labels are only there only as information, not part of the aesthetics, but they have to be there. It’s funny because we never have labels in our own shows in museums. We refuse to have labels, and all we have is an exhibition guide telling about the works that are around, so we don’t have labels next to the work. But, with the wall paint, we also had a whole series of performances where we were painting the walls of the galleries white for maybe 12 hours and then washing down the paint so it would be dripping and making a big mess, and then we’d have two house painters painting the gallery over and over again for the duration of the show.

With the “Named” paintings, though, we really wanted to see how different the white-painted museum walls would look when they were side by side. And they are very, very different. It’s funny that MOMA has a thick layer—they have the whitest walls—but when you hold them up against others, it’s hard to tell. Newer institutions the New Museum have a very white tone. The Guggenheim has a very yellow tone. So, it was fun to make a room that would actually allow for a real comparison.

These paintings, with their ancillary, overlookable nature, seem to be in the vein of your powerless structures.

Dragset: Yes, in a way. Of course, it’s dealing with the power of the object. Sometimes we like to elevate an insignificant object into having a larger significance, like with the labels. Other times, we take something that is seen as very powerful and render it powerless, as in Prada Marfa. Critique like that is not really a powerful in an urban context—you have to put it in a desert. It doesn’t have any function there, really, so it’s lost. We also deal with the representation of a certain object, and how it could be perceived differently than what it is. And, in fact, we made the labels in this classical style, some engraved into marble, some oil-on-canvas with a very painterly quality, and that’s because these techniques are seen as more valuable art forms by the general population—that’s what is perceived as real art. So, we’re playing with power and absence.

I would imagine collectors love these series, because as paintings they are so liveable, unlike some of your other work.

Dragset: Yeah, but on the other hand, it’s also conceptual, of course. You have to sort of be an art collector to understand both of its sides.

Now I know that you have contributed one of these wall-label works—a painting referencing David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS in 1992—to an auction benefiting New York’s AIDS Memorial, which is being unveiled this fall. How did you come to choose that piece?

Elmgreen: He was an artist who made sense in that context, we found.

Dragset: We call them “Self-Portraits” because it’s our way of showing our respect to the veteran artists who came before us, and their times.

Elmgreen: I think it’s a piece a lot of gay men can relate to. The AIDS crisis influenced many of our sensibilities in a way, especially through the work of those who were directly affected.

The story behind the AIDS Memorial is also one of people who were long powerless gaining recognition. Power and the lack thereof is one of your more resonant themes. What makes you so interested in plumbing the mechanisms of power?

Elmgreen: Power has a tendency to be reactionary in some way. If you are in a powerful position, you want to keep your position and so you want to keep the structure as it is, which is very unhealthy for society, very unhealthy for art, and very unhealthy for any form of evolution. It needs to be challenged. I think there’s a perception through media and a general disillusion that it’s not possible to challenge a lot of structures. But it’s wrong to speak about power structures, because the structures are nothing in themselves, as we know from Foucault—they only have power insofar as what we agreed upon. If we agreed upon something else, they would have changed. They’re not a fixed feature.

So, for us, it is interesting to see how is it possible to change social systems and the physical features even of the art world, because we think that especially now, when there are a lot of financial considerations at stake, people who are successful in going about their business in a certain way might not be willing to change. For instance, there are the openings, where we first invite a special little exclusive audience to come and view, and then it’s opened for the rest of the public later—but actually how interested is a private commercial gallery in that audience coming, looking at that exhibition, or is it just a charade? And would it maybe be possible to change the format of openings?

It’s important to have curiosity. Is it possible to do it in a different way? Just a simple change can show how fragile most power structures are when it comes down to it, and how easily it is to change something if you just agree upon it. It might be very naïve, I think you can test this notion out on a microscale and show people, “Hey, we changed this, and they accepted it. Maybe it’s possible to change some things on a bigger scale.”

Well, now you have an opportunity to show how power structures can be changed in your organization of the Istanbul Biennale, which you will be curating in 2017. How did you get that opportunity?

Dragset: We actually got invited by the biennale officials to come up with a proposal to be entered into a competition with others. And then the board decided to commission us to do it.

It would seem like giving you two a biennale could be a very dangerous thing.

Dragset: [Laughs] We’ll see, we’ll see. For a large part we will let the other artists speak for themselves. Of course, we will select artists who we think can bring something interesting to us, and that is of course relevant to what’s going on now.

Elmgreen: One thing that we can reveal is that we’re not going to make a biennale that grows out of a specific concept and that then has to crystallize into projects that illustrate our idea only. As artists we often find that process quite painful, and a show like that is much less interesting than the actual works themselves. So we’re trying to approach it a bit from the other direction, where we look at spaces, we look at artists, and we combine them. We do have had a concept, but it’s not a concept that is so overly detailed that it doesn’t have room for taking some different turns according to the artist’s project. And it’s also going to be a biennale where we hope to create intimate experiences and not only have works that are referential.

What you often will have if you have a very defined concept and then invite an artist who has to relate to that very closely—for instance, they have to refer to something already existing in history, or a political issue, or whatever—is that you as a viewer lose a bit of your immediate, intimate experience in front of the work. That is one of our main criticisms of many good biennales, but it is a common tendency among biennials over the past several years that you would have a feeling that you were supposed walk around the art and tick off boxes and say, “Ah, yes, yes, I see now. This is about that.” And you don’t get really the big surprise or an intimate experience or the strange experience where you are not really sure what you are in the middle of. For us, that is really important.

There certainly has been a trend among biennales toward a very overdetermined, authorial voice where the curator is like a film director making sure the artists follow a script.

Dragset: We certainly want to take on another role. We’re easing into this, so we’re learning as we go, but we totally see it as an opportunity to step back and give artists a place to shine—though of course, as artists ourselves, our personalities will always play a role in a way. It’s a huge responsibility, and it’s a real challenge that we’re already so invested in it, but I feel the goal is really to give as much love and space and possibility as we can to the artists who are going to show in the context there. That’s what we can do.

Elmgreen: Of course, it’s going to be still be the greatest biennale of all biennales [laughs]. That’s the goal. It’ll be a very hard competition next year because there’s also Venice and dOCUMENTA too.

Do you think there’s a little biennial exhaustion? You were saying that as artists you feel they can be constraining. Is that a widespread feeling, that there’s a need to open things up more?

Elmgreen: In terms of biennales, I think they’ve been usually popular for almost 20 years now, right? Now everyone feels like you need to try something else. There’s a huge number of biennales, and sometimes we’ve seen the same curators do several of them, and the people who travel around see more or less the same thing. It should be exciting. Because we’re skeptical about biennials in general, we want to open things up to poets and other modes of creativity. We’ve never been so lucky. Also, having been part of three Istanbul biennales and another big urban project in Istanbul, we love the city and we’ve gotten to know people there over the years. We want to make sure that, if you’re engaged with the exhibition, that you can totally get something out of this.

Dragset: Of course, the relations between Turkey and Europe, and Turkey and the neighboring countries, is super interesting. It’s been extremely modernized over the past 15 years, but at the same time religion plays a different role than it did before. It’s super interesting for us to try to make a biennale there, because the city tells a lot about the world, actually.

The president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has been widely criticized for cracking down on liberals, and now in the wake of the attempted coup he has consolidated power more than ever. Do you feel like you have to engage with the political system in your curation of the biennial?

Dragset: Initially, no, and hopefully not along the way. The foundation that produces the biennale is an ongoing organization, we have no direct involvement with any governmental agency. The only thing we had to do is meet with one local mayor. It’s always when you come to know somebody, though, that you discover all these layers.

Considering that power is one of your themes, and the political situation there is so fraught, do you feel a need to be critical of an oppressive power structure?

Elmgreen: Well, we decided to not engage. The basis of it is that we decided from the beginning in our initial discussions with the foundation that hired us that we would not let the government decide what the biennale should be about.

Dragset: Not in one way or the other way. We also don’t want to be an antithesis to a situation, because that puts everything on such a low level. It’s the same reason you don’t want to go into a battle with Donald Trump or far-right political rhetoric in Europe because it takes out all the complexity and the interesting issues if you’re forced to respond to it in a direct way. Of course, our work is always site-specific, so the local situation part of our consciousness when you curate. But the political situation is not going to determine what kind of constituents we give a platform to speak.

Elmgreen: Also, they trust that our vision represents something very different from the regime. That will be a dialogue that in any case will remain in what you see in the exhibition.

It sounds like you’re saying that if you make part of the biennial directly relate to the government, then you’re letting the government be the curator just as much as if you gave censors the reins over the show in a way.

Dragset: That’s what I think can be a danger for biennales often, is that they feel certain obligations to include or deal with things in a certain manner that maybe doesn’t have a real engagement, if you know what I mean. For us, it’s important that we keep our integrity in what we include, that we make sure the issues and topics are important to us as well, and that we show an alternative to some of these political decisions that are made.

We were participating artists in the 2013 edition of the biennale when there was an uprising in Gezi Park and there was police violence, so we made a room where we invited five young men to write in their diaries about their lives every day through the biennale. There would always be one person missing, and you could sit in his place and read his diary, and they all came from different parts of society, had different occupations, and were writing these stories about their everyday experiences, political experiences.

It was part of a larger project—we’ve done it in Paris, we’ve done it in Hong Kong, we’re going to do it in New York, and we’re going to make a book of all these documents.

Elmgreen: It turned out a couple of those guys from Gezi were also queer activists, and that actually the queer community in Istanbul was one of the most active groups in the whole Gezi discussion.

As the world starts to get stranger and darker, what is the role of a biennale? Can a biennale achieve something positive for society?

Dragset: We can certainly show that we can exist together, because we will have artists coming from very different geographical origins, different backgrounds, different preferences, different sexes, different social statuses. I think the beauty of the biennale is bringing people together and being a platform for discussion.

Elmgreen: And also different kinds of discussions, unlike a symposium or a conference, which is important. I think art can talk in a different way to people. It can be an emotional experience or irritating, intellectually stimulating, or all these things at the same time.

Dragset: And it’s a non-commercial environment, so you also have more or less equal conditions for visitors coming into the biennale. It doesn’t really matter if you’re a billionaire or if you’re a poor art student, which is different from the VIP culture that we see in the art world in the commercial galleries. We really believe that this coexistence, this dialogue, is the force of the biennale. The biennial should be a movement to bring people together, to bring audiences to the city and have an exchange, and also disagreement.