A towering figure of the postwar era, Ellsworth Kelly charted a singular and often solitary artistic path. He ventured to Europe twice—first as a camoufleur for the Ghost Army during World War II, then as a questing painter on the G.I. Bill—and brought back a bright and lively new style of American painting, seductive in its grace and generous in its joy. Steeped in the intellectual rigor of Malevich yet bursting with the splendid colors of Kandinsky and Léger, Kelly’s shaped, often monochromatic canvases and reliefs were unlike anything else when they debuted in the 1950s.

In the years since, his art has been embraced into the greatest museum collections in the world. Kelly himself was heaped with honors; two years ago, President Barack Obama gave him the National Medal of Arts to mark his 90th birthday. But, like his friend Alexander Calder, Kelly always remained a man apart, creating work that delighted crowds and the cognoscenti alike yet never linked up with—or yielded—a movement or school. What could be done with such egregious beauty?

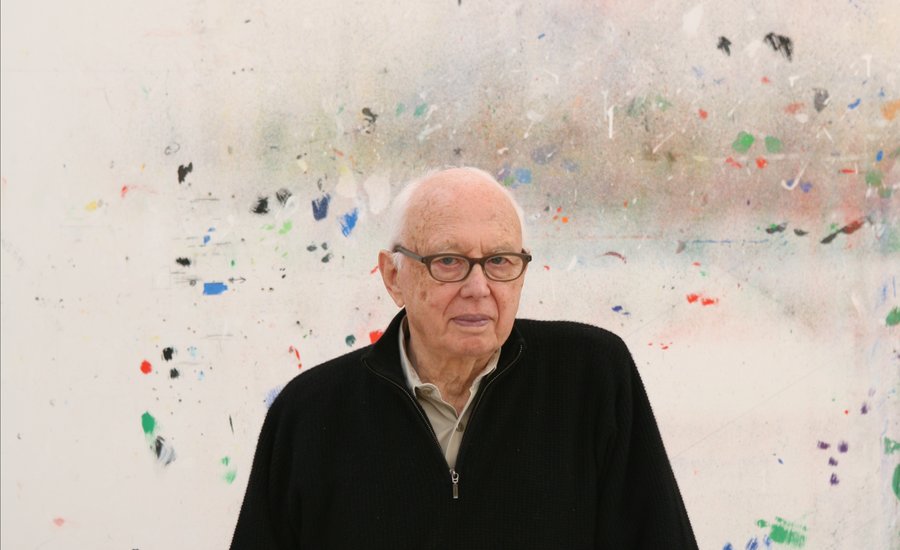

This distance suited Kelly, who passed away last Sunday at the age of 92, because his best audience was himself. Having moved from New York City to the upstate hamlet of Spencertown, New York, in 1969 to live with his partner (and, later, husband) Jack Shear, the artist immersed himself in his natural surrounding and his paintings, which gave him great pleasure. Other renowned American artists were his neighbors and friends, and his many guests included famous collectors who traveled long distances to land their helicopters in his backyard, which he converted into a sculpture park.

This summer, to mark the completion of Phaidon’s definitive Ellsworth Kelly monograph, Artspace enjoyed the privilege of being one of Kelly’s guests, sitting down with him in his spare, light-flooded studio to discuss his art, his career, and his inspirations. Here, in one of the artist’s final interviews, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Kelly about his life’s work.

RELATED LINKS

Watch a video of Ellsworth Kelly on How He Draws Inspiration From Nature for His Art (Part One of a Series)

Order Phaidon's Ellsworth Kelly Monograph

*All photos that follow are from Ellsworth Kelly's home and studio in Spencertown, NY, unless otherwise indicated*

When did you first become drawn to art?

When I was three years old we lived in Pittsburgh, and the staircase from the upper floor came down right in front of the front door. In those days, in the mid-1920s, we never locked the front door, so the milkman would open the door and put the milk and butter and cheese right on the mat. Now, my mother told me this story, but I remember it in a way: the action of coming down the stairs and seeing this yellow pound of butter, I went to it and stepped on it and stepped on it until it was all flat. And so my mother came out and said, “Look what you’ve done... you’ve made art!”

I feel that has stuck with me. I don’t like bulk. Thickness. Three dimensions. My paintings have always been planar. I only like thick things that are really thick, like Richard Serras for instance. That cube in Berlin [Berlin Block (for Charlie Chaplin), 1978], you can feel it—you can feel the thickness of it.

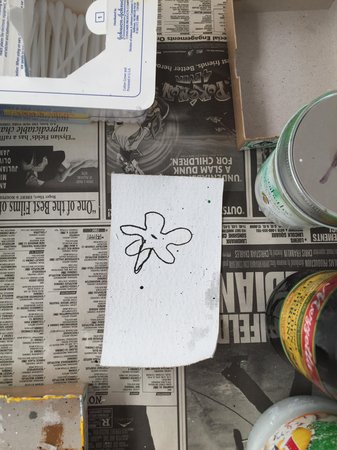

Birds have also had an important influence on your aesthetic, and from a young age you were an avid birdwatcher. What was it about birds that so attracted you?

I have a funny love affair with birds. I was sick when I was five, and my mother and grandmother gave me a bird book. Then, as soon as I was old enough to walk out into the woods, they sort of drew me in, almost like in some French movie where people are drawn into the woods. The mystery of it. And I remember the first bird I saw, which was a redstart. He was black with red spots on his wings, and he flew ahead of me from pine tree to pine tree, and I sort of felt like he was leading me to somewhere.

I remember when I was in junior high school we had a new science teacher, and one day he said, “We’re going to go on a bird walk. Does anyone in the class know of something we could see?” And I raised my hand and said, “Yeah, I live near a lake.” The lake was the town reservoir, and I used to climb the fence and swim in it, so we went there. I never had glasses when I was a kid, but I said to the teacher, “If you look up in the tree there, there’s a blue-winged warbler.” He looked up and said, “Good eye.” From then on he would ask, “What else do you see?”

When you’re young like that, you’re small. You’re not a big body that scares them. The birds have been treated so badly, I guess, since the early part of the world, because they really don’t let you get too close unless you’re very quiet. And that’s part of the fun of it—to get close enough to see how very beautiful they are.

It’s like that with my paintings. I remember when I was living outside of Paris one summer, they had a movie house in the little village and they showed Cousteau’s underwater photographs of fish, and the whole audience went, “Oooh! Ahhh!” And I said, “Why don’t they do that to my paintings?” [Laughs] I want them to faint. Or to have the Stendhal effect, leaving them crying.

Nature is such an abiding theme of your work. How do you see your art as relating to nature?

Well, we’re part of nature, and I think we all love bodies. There’s nothing like a body that you connected with and love. I know someone wrote a little bit about the fact that some of my shapes and curves have a connection to parts of the body, but I don’t try to do that at all. It just comes out. After I do a painting sometimes someone says, “Oh, that looks like a breast,” or a rear end or something like that, and I would say, “I didn’t plan that, but I can see what you mean.” I want my paintings to be voluptuous in some ways, and bodies are very voluptuous.

What about your color palette? Does that derive from nature as well?

Color is another thing—I don’t understand exactly how I do choose color. I like all colors, except for pale colors. I’ve done very few pink paintings, or light blue. But I do like gray. I’ve done a series of gray paintings. I know once during the Vietnam War I did a series of very colorful paintings in New York, and what people said was, “This is too cheerful. Who wants to see these happy colors right now with these awful headlines in the papers, and all the boys and women there in the war.” So I said, “I’m a little ashamed that I’m so cheerful,” and the next set of paintings was all gray. And then I didn’t sell any of them. [Laughs] Until later.

Looking around your studio, I can see you’re working with white again. What does white mean to you?

It’s light. It’s life too. It reminds me of the yellow that I painted last week. I didn’t do it myself—I had it done for me, because it’s quite large, by two women who work with me and several other guys. As you looked at that yellow it hurt your eyes. It was really hurting. My whites hurt a little bit too, because that’s light.

In my last show at Matthew Marks there were four yellows, and they were all different. And I did a yellow piece [Yellow Curve, 1990] in Frankfurt once at a place called Portikus—it’s a building that has columns in front and it’s just a small room. Kasper Konig, who ran it, called me one day and asked if I would do something, and I said yes. Every time I get in an airplane, I look out on the tarmac before takeoff at these huge curves where the planes move, and I think, “Why can’t I do a curve like that?” So I thought of that immediately and I asked Kasper, “What kind of floor do you have, and can I paint it white?” So I put a big yellow curve down on that white floor that would touch on two walls and come all the way around and come to a point.

One thing that is so compelling about your work is that, despite its deep kinship to architecture in it emphasis on flatness, scale, shape, and frontality, you couldn’t call it decorative. It really fights for its space.

I don’t like decoration—it’s like bad painting. Because, to me, a painting really has to really mean something. To me, I mean. It’s hard to say what it means except what you feel and what you can do with it by looking and investigating. I think Diane Arbus said, “If you investigate enough, everything becomes abstract,” and I like that, so I use it. Everything has to relate to the architecture, like that door back there that’s open—it’s a tall rectangle of dark next to white. I always felt there’s too much in some of the pictures. I mean, I like Kandinsky very much and Léger, who both work in colors, but Kandinsky can have a lot of little things. But I’ve always wanted my works to have their own large space, and to be able to relate to that shadowed door and to everything else in the room.

Another artist whose paintings can achieve that kind of architectural monumentality is Picasso, who was a major influence on you as a young man. Can you talk about Picasso and your experience with him?

Well, you know, in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but mainly in the ‘50s, you had to get him off your back. I had gone to school in Boston [at the Museum School at the MFA Boston] after the war, and Boston was very backward. I remember once I had to go downstairs to the museum’s offices and I saw the secretary had a little Braque behind her, and I said “That’s a Braque!” and she said, “Yes,” and I said, “Why isn’t it upstairs in the museum?” and she said “Oh, they don’t want it.” So when I was in Boston I hitchhiked all the time to New York to see all the galleries, and it was still a good time to see Picasso and Matisse, who were very old, and Léger and Miró. And I went to MoMA to see the first Malevich, white on white, and the Kandinskys.

But I’ve always loved Picasso—he was the first person who really grabbed me.I think he’s so wonderful because he shows artists how to make a great painting. He is great with color, of course. You almost understand his color, whether it’s red and blue, or green, yellow, and purple. But with Matisse I don’t understand his color—I mean you think about it and look at it and even talk about it or look at the paintings, but it still eludes you. Matisse’s drawings, though, take your wind out, because what he does with a pencil or ink, the shading of the pencil, the weight when he draws—it’s just magical.

You met Picasso at one point, when you were in Paris. How did that happen?

I had a hotel room not far from his studio, and one day I was walking on a very narrow street that came out on his studio when he started backing up the street in his Hispano Suiza car. That narrow street barely fit his car, so I had to push up against the wall, and the window opened and he looked at me with these black eyes and said, “Do I know you?” He seemed very small in his backseat and he was immediately conscious of my smile—I must have gone, “Ahh”—so he offered me a ride. But I didn’t speak French so I knew the conversation would have lasted about three minutes, probably, so I said no.

Later I tried to see him in the South of France when I went with two friends of mine to Antibes, where he had the castle, but he had just left. At that time he was making pottery so we went out to his studio in Mougins to see what they were doing out there, but I didn’t see Picasso at work. Finally, we went out to where he had another little cottage, and we saw he was working with his two little kids. Françoise came to the door. I said, “Can we see Picasso?” and she said, “Non, non, et non.”

Another critical influence on your work was Monet, specifically his late near-abstractions, which for years were very hard to find because they were so out of favor. How did you come upon these works?

Monet changed me, seeing his paintings. For years, all I knew were his ones from before 1900, like the haystacks. Then I saw two late Monets in Zürich from when he was going blind, and they moved me so much. I remember it was all that I could talk about, and I asked my friends, “Who has seen these?” In 1952 I went to Giverny with a friend who was a painter, and no one was there. We went to the garden, we saw the pond, we saw the bridge, and I remember walking by the studio because we knew where it was. We went up the stairway into the second gallery, and it was stuffed with paintings—you could barely open the door. I can just go on about this.

Tableau Vert (1952)

Tableau Vert (1952)

This visit inspired your first monochrome, Tableau Vert, which you painted upon your return. Why?

His pond, his bridge, and all the grass underwater, fascinated me. After seeing it I wanted to do a painting in one color. I went back to my studio and there was a small painting that I had under-painted white. I thought, “I’ve done a painting in five colors [Painting for a White Wall, 1952], let’s see if I can do one as a monochrome.” When I finished it, I said, “No.” So I wrapped it up—it was one of the last pictures I did in Paris—and I kept it wrapped up until 1987 when the curator of a show I was doing in Lyon asked me if I’d ever done a monochrome. I said, “I have something like that from a number of years ago.” So I ripped open my painting, and there it was, greenish blue. I gave it to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Your years in Paris after the war, from 1948 to 1954, were pivotal to your development. You met many of the greats and worked for a time with Jean Arp, whose chance-based techniques were a major influence on you. How did your experience change you?

I didn’t speak French when I went there and I didn’t read it either, so I was very much a loner. I didn’t come away with too much French. But I had some close friends who were American and European and who spoke English, and it was a great time. I came back in 1954, and I think I brought back a different kind of color. If you think of Rothko and Barney Newman, of course they were great colorists—very different, though. Rothko was more muted, and I felt my color came from Kandinsky and, say, 1912 Léger. He was painting color when Picasso and Braque were doing gray. So my first show back in the United States was half the early pictures, and it was just too bright for everyone.

Today you are unquestionably a great American artist, one of the greatest that the country has had in the modern era, but the country didn’t always know what to do with you. You were born in America, went to Europe for the war, came back to study art in America, returned to work in Paris, and then when you came back to the United States in the ‘50s your work was seen as European. Do you think of yourself as an American artist?

Well, I’ve always felt that I am an American. It’s like how Al Held, Jasper, and Rauschenberg felt, whom I like very much. Jasper was so great. He was here looking at my pictures last week and Jack told me that he looked at every picture, the black-and-white ones. But you know the way he is, he is difficult to talk to.

Looking back on your career, what are the achievements that you are most proud of? Do you see the shaped canvas as your signature achievement?

Yes.

In the 1950s you also began making reliefs, overlaying one flat shape on another to create multidimensional abstractions. What inspired you do make these?

When you take it back to Renaissance, things were flat. If you are painting like they did in the Renaissance, you are painting a picture. But when I make a relief, it means that I am fooling the eye. With my older paintings I never thought of doing that. The first relief work that I did was in Paris.

Green Relief With Blue (2011)

Green Relief With Blue (2011)

If your reliefs aren’t pictures, then what are they?

Fragments. Look, all day we are looking and moving. Wherever we move it seems like we are seeing millions of things a day: a bus coming by, or a car, or people moving, or objects. I believe doing the relief work is more true to mimesis, painting what you see.

What is it about the experience of painting that has made it such a lifelong passion?

Well right now this... [gestures to his breathing tube] for my painting. Seventy years of inhaling turpentine. So I’m a little mad at painting. You know, this is part of it. And a lot of artists have died young. It’s a dangerous job.

What inspires you to paint these days?

I have to wait, and it’s a number of things that collide together, and it’s difficult. More difficult now. At my last show I was feeling like I’ve done enough. I feel like I’m squeezing the blood out for a painting. But I admire someone like Picasso. He is built for painting, and his paintings show it.

What is your routine when you wake up? What is the course of an ordinary day?

Right now, there are a lot of things other than painting that occupy me, like books, letters, and things like that. I’m still getting back on my legs because sometimes my legs, especially my knees, bother me, but they are getting better. I have a guy who comes in and exercises me, and he pushes me.

When you are working these days, what is your process? Do you put the canvas directly on the wall?

Yes.

Are you still the one doing the painting, laying down the paint yourself?

Yes.

How long does it take for you do a particular painting?

You have to wait for the drying. Black sometimes takes a month. It takes three or four weeks for white. You can see that they still have the ground I laid on them, and that is three coats, or until the color becomes solid. So I work on six at a time.

How many paintings do you have in storage?

Well, I have done 1,000, so maybe 500.

How many have you held on to?

Maybe 200. The ones that don’t sell. [Laughs] The ones that come back.

What do you do with them?

Every once in a while I pull some of the paintings out of the racks. It is new to me that the red is brighter than the blue. I said “I am not sure if I like that.” I thought about it for a couple of days. I came in to sit and look at it and I thought that is what I like about it, that the red is brighter than the blue. I think like that.

How do you mix your colors?

I just use two colors.

Do you always mix them the same way?

No, each red is different. I remember there was a show of my work that I went to at the Whitney where there were three colors—red, blue, and green, which are the television colors—across 12 to 15 paintings, all of them quite big. A little boy came up to me and asked, “Do you paint the same red in each picture?” I said, “Why don’t you come walk with me and look at the same pictures and see if I do?” He said, “No, I see the red is a little different in that one.” Then I said, “Well, they are all different because when you mix the color, you don’t know how much you put in it.”

Because I don’t do it like how some people do, by weighing the pigment when it’s powder, or working on it like they have a recipe to make red. I keep track by how many tubes of paint I put into it, like counting two and half tubes or four tubes. But I never paint the same color. I can’t. And the yellows are the same way—I had four yellows in my last show and they were each different according to how much orange was in it. I like when the red is very hot, with the yellow edge on the red.

So you’re kind of like the chef that measures ingredients by a pinch of this, a handful of that.

Yes. You’re always making the spaghetti a different way.

How do you think of your older paintings? Do they evoke memories for you?

No, I sort of just feel them. There is so much emotion in them. They give me great joy. And I just love colors. You look at one and sometimes you feel it has this sweet juice. That’s why I stick to colors, and to black and white too. I think black and white is a wonderful combination—both sides of color and no color. I sometimes like to start something in black and white. The idea is strong like that.

Your career has been astonishing, so rich and full of event. It’s incredible to hear you talk about it.

Well, I always wonder what is going to come out when I just talk and tell stories. It’s been fun, this life, especially since I am so close to 95. It’s beautiful. It’s been a long life. I have had so many friends now, so many artists that have done kind things.

I used to look at Roy Lichtenstein a lot because he was a good friend. We used to talk a lot about what we liked, like Picasso. I remember there was this big Picasso show about 30 years ago I guess at the Modern, so we started going around the exhibition and talking. After I while, as we were looking around, we realized that a whole bunch of people had gathered. Then I realized that we were hiding the paintings—but they wanted us to keep going and continue talking.

Roy, of course, was quite appealing. I think he did the same thing with color, and he also has something else. His subject matter is very prevalent—he did rooms, modern nudes—and he tried I guess to get the same result in some way. Because you can really see that he loved doing it.

Now I talk to Jasper—he is a fantastic artist—and Frank Stella, and they are my friends. They all experienced human suffering, and look at what they did. If you love painting you get a real jolt—you get it, and it is what it is. It’s very hard to cover it up. You can’t really get rid of it.

That is how I am—I say don’t ask what it is, but see how you feel. Picasso is a great teacher. He teaches you how to look and enjoy a great painting, and all the great artists are that way. I’m still searching. I like looking.