For 10 years, from 1984 to 1994, the painter Henry Taylor worked as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital near Santa Barbara, California—the now-shuttered treatment facility named in Charlie Parker’s “Relaxin’ at Camarillo,” after the jazz legend spent six months in detox there, and referenced more obliquely in the Eagles hit “Hotel California.”

Taylor worked in Unit 18, with schizophrenia patients, arriving around three or four in the afternoon and staying until midnight. He often came straight from art class, at Oxnard Community College, where he was studying with the painter JamesJarvaise, or from CalArts, where he enrolled during his last few years at Camarillo at Jarvaise's suggestion.

At a certain point Taylor’s studies and his job started to merge, as he carried a sketchbook to the hospital and made drawings while on shift—intimate and sometimes surreal portraits of patients, as well as haunting glimpses of the spaces of their confinement. (Almost no one in Taylor’s unit was released during the time he was employed there.) Some of these sketches evolved into more complex paintings with multiple figures and architectural views, works that give us a bigger picture of life at Camarillo, as in the evocative scene of medicated patients in the hospital’s day hall, below, which was damaged in a fire while in storage.

Working with the brother-and-sister curators Michael and Yael Lipschutz, Taylor has chosen paintings and drawings from the series to inaugurate his new project space HenryTaylor’s, at his studio/apartment in downtown Los Angeles (right across from the new Hauser & Wirth gallery complex). These early works, and the experiences that inspired them, clearly shaped Taylor’s sensitive, expressive, and psychologically intense approach to the figure—the qualities that make him one of the most intriguing portraitists working today. “I learned not to dismiss anybody,” he recalls. “It just made me a little more patient, a little more empathetic. It taught me to embrace a lot of things. A lot of people will avoid a person who doesn’t appear normal, but I’m not like that.”

"If you know Henry’s work, there’s most always a sense of a psychological connection with the sitter in the paintings," says Yael Lipschutz. “The fact that for 10 years he had really intimate relationships with these patients, who considered Camarillo their home, made me think about the types of people he’s drawn to in his paintings. There’s a diversity, but people who are homeless, or who have mental illnesses, make up some of his body of his work outside of Camarillo. These people are sort of invisible, to their families and to the public. They’re not to Henry.”

Below, Taylor gives Artspace some background on this formative series, which is on view through April 30.

Day Hall, 1992

"I was always carrying a sketchpad with me; I’d go to parties, and if I got bored I’d find some paper and draw—it’s what I did. So, I got in the habit of it at work. A lot of times I’d just sit in the day hall.

"This was a typical scene. A normal day, almost—my still life of the day hall. It was a certain time of day when everybody was there. People went to classes or groups during the day, or they would go for a walk, depending on their level of functioning. Some high-functioning people had little jobs, maybe working in a cafeteria. But at 3:30, everybody was coming in, and then they had to get four o’clock medications, and that would be the start of my day. In the picture you have a doctor in a white coat with his arm up, getting ready to give somebody a shot."

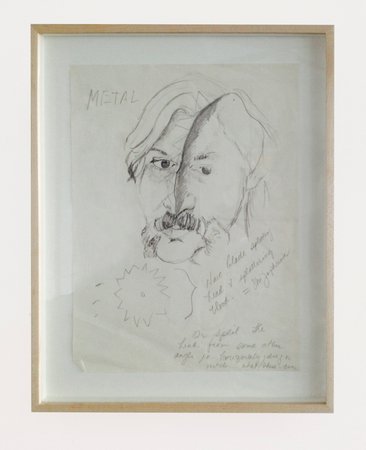

Split Person, 1992

"I was reflecting on a scary dream I had. That was my connection to this patient, because these delusions that they have are real to them, and we can sometimes just snap out of things and they can’t ever. It helped me empathize and understand, in a practical sense. It was like, 'Damn, what if I had my worst dream 24 hours a day, in my waking moments?'"

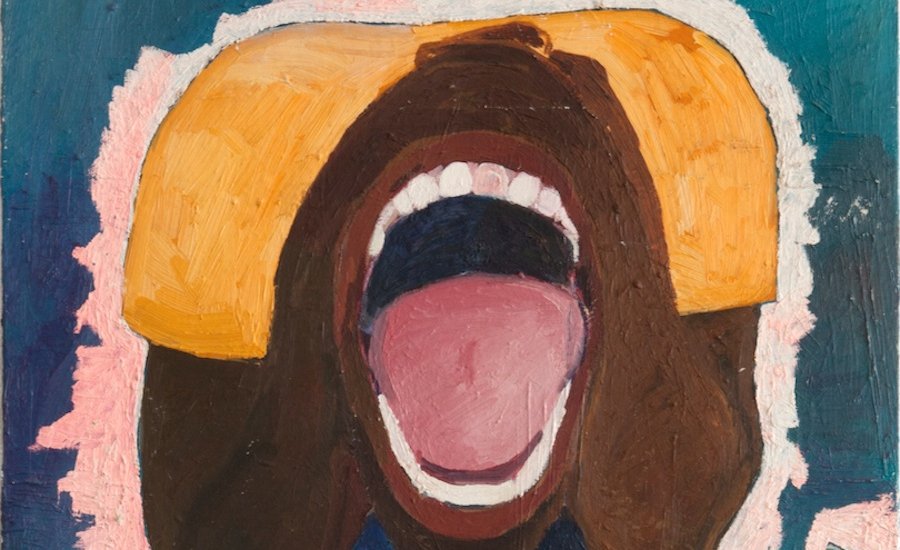

Screaming Head, 1990

"A lot of people were very lethargic, or depressed, or maybe just very introverted. They were also exhausted, after being forced to walk around or go to groups or leave the unit. And they were medicated—thorazine is like a liquid straitjacket. People were sort of contorted in the positioning of their bodies—a patient would clasp his hands together behind his head. And if you look at that long enough, you start to see something. It’s like, 'Wait a minute, his head just became his mouth.' You can just draw a head, or you can be intuitive and take that liberty."

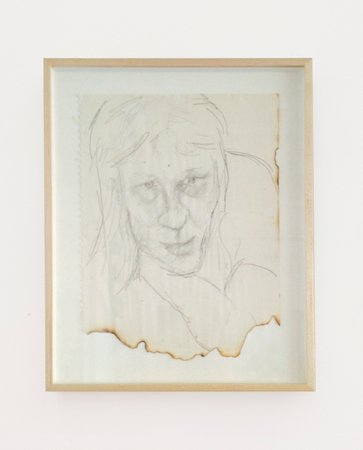

She Called Me “Bill,” 1990

"At the hospital, you'd see people all of a sudden just shouting at things. And you'd realize how painful it is, especially when you know the person. You'd come into work and see one of your favorite patients, someone you really connect with, having a bad day—they may curse you out and call you all sorts of names, but you know that tomorrow’s going to be a different day.

"Jeanette was a favorite of mine. She called me 'Bill'—I guess she associated me with someone in her past. When she was having a bad day, she would call me all kinds of names. And some days she’d be smiling, and she’d say 'Bill, you had the baddest low-rider,' and I’d just crack up. That was my girl! Jeannette, bless her heart."

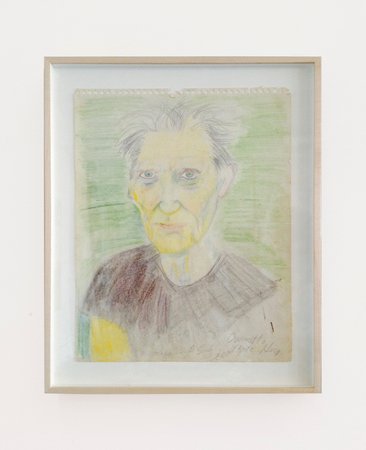

Catatonic, 1991

"I took nursing and psych courses, so I was what you’d call a psychiatric technician. I was like a mediator between the client, the patient, and the doctor. Normally I administered medication, gave shots, did treatments, charted all the patients. Sometimes you would study things and then find a patient that had a certain diagnosis that you’d never seen. This patient, I never forgot. It was like, 'Damn, he’s really catatonic—he’ll just sit there and not move.'

"When I look at these drawings, I remember pretty much every person. I mean, I think it was 20 drawings, and I know who at least 18 of them are. And I remember them, because I was on one unit for eight years. Half of them were there probably 10 or 15 years. I ran into a former patient of mine on Skid Row one day, and I asked him if he knew who I was, and he said, 'Yeah, you’re Henry.' So I took him to my studio and tried to find out why he was on the street, because I knew he had to have gone AWOL. Here’s a person that I’ve known for eight years, I’ve given him treatments. What was I going to do? So I took him home and called my old position."

The Door, 1994

"That was the exit door of my unit. That door, everybody wants to get out. People would try to go AWOL. It was sort of significant to me—I remember the curator of my MoMA PS1 show, Peter Eleey, said, 'You only have one painting in the show that doesn’t have a figure—do you know which one it is?'"