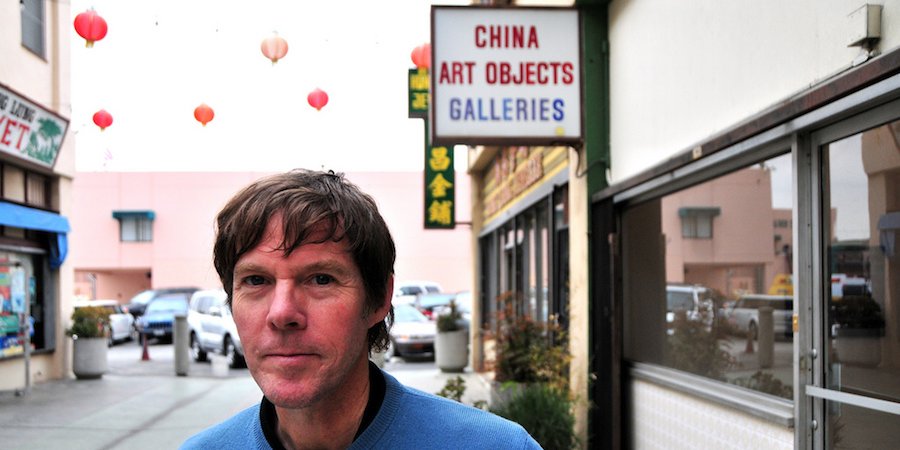

Before the Los Angeles art scene was the Shangri-La—or hype machine, depending on your point of view—that it is today, now spreading from the Eastside to Hollywood to Culver City and beyond, it was a tiny enclave of cool ensconced in a gritty, peculiar setting: the city's historic Chinatown. Why there? Largely because of the energy generated by one renegade artist-run outfit, China Art Objects Galleries, that opened its doors on Chung King Road in 1999 and helped usher in the laid-back-but-polished, multidisciplinary era of L.A. art that has characterized the past decade and a half.

Founded by Steve Hanson, Giovanni Intra, Peter Kim, Amy Yao, and Mark Heffernan, the gallery ran on a madcap sense of determination that its coterie of artists—mostly friends—deserved to be taken seriously. It was also the epicenter of a hard-partying lifestyle that fueled endless nights of creativity and resulted, tragically, in the death of one of the gallery's most dynamic founders. Due to the professional sheen that has glossed over the city's art scene, a concomitant of the international money and attention that has descended upon it, those days are now firmly in the past.

Based in Culver City since 2010, China Art Objects (as it is usually known) is now run by Hanson and his wife, Tuesday Yates. To learn the story of the seminal gallery and the rise and fall of the Chinatown scene, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Hanson about his ongoing 15-year experiment that has reshaped L.A. art.

This is the first installment of our new NADA Network series, focusing on galleries affiliated with the New Art Dealers Alliance.

How did you first get involved with art?

I just always liked art, and then I went to art school at Art Center. But I didn’t finish school at Art Center—I got a job in the library there instead and worked there for 12 years. So I was still sitting in on the classes and meeting all the new people who were coming through. It was like being in art school for 12 years.

The Art Center College of Design in Pasadena

The Art Center College of Design in Pasadena

This was the Mike Kelley era of Art Center?

Yeah, Mike Kelley was there. He started there in ’93, and he was a big influence. And I met a lot of people there who were starting their careers, like Jorge Pardo, who was a good friend of mine and who also worked in the library, and Pae White and Frances Stark and Sharon Lockhart and Laura Owens, even though she didn’t go there.

What was Art Center like at that point? It seems like it was just starting to gain influence in the L.A. art scene as a kind of scrappy alternative to CalArts.

I don’t know if it was scrappy, but it was small. Grads and undergrads could commingle, and there were only a few good classes and good teachers. Richard Hertz used to work at CalArts when that was the hot thing in the ’80s, and I don’t know if he got fired or what but he came to work at Art Center and started to bring in the good teachers and be all pro-student, getting them weird grants and stuff. The school hated him for it, but the students loved him for it. And I think that’s what changed everything.

Who were the most exciting teachers there?

Mike Kelly. Patti Podesta. Stephen Prina. Mayo Thompson. Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe was a great teacher. And different people would come in and out—there was a big visiting-artist program at Art Center, and they would hire students to drive them around and things like that, so you could meet these important artists.

Steve and Giovanni

Steve and Giovanni

How did you come to start the gallery?

It was just one of these things. Me and Giovanni Intra were out at a desert rave, a little bit high, and he said, “Let’s start a gallery.” Everyone is always coming up with ideas like that and just never following through, but for some reason we did, even through there was all this stuff that should have made us say, “Oh, fuck it.” Like, we failed to find people with money, since we didn’t have any money—Giovanni was still in school and I was working at the library—so we had to get two other artists who were just about to graduate. Then one of the other artists’ landlord came in and gave us $1,000, and it was like, “Wow, an investor!” So it became just the five of us together, building it out ourselves to follow this dream. And we kept pushing.

Tell me about those three others, Peter Kim, Amy Yao, and Mark Heffernan.

Peter Kim was an artist who studied illustration at Art Center and was just this cool guy. Amy Yao is still an artist, she went to Yale and has been in New York for a while. Then Mark Heffernan was Peter Kim’s landlord, so he wasn’t an artist, though he was a musician. But one by one they got uninterested, and Giovanni died.

What was the L.A. art scene like at the time, in the mid-‘90s?

Well, it was small, because there was a big downturn in the early ‘90s. But as always with a downturn, all kinds of people popped up. So all of a sudden everyone was paying attention to L.A., especially the UCLA grad program, with Mark Grotjahn, Jon Pylypchuk, Evan Holloway, and Liz Craft. All these people were coming out of there, and there were articles in Spin magazine and other weird magazines that don’t usually write about art. Dennis Cooper was the one who covered it for Spin, and he was a writer who a lot of artists were really into just at this moment when people were doing weird cross-pollination things with writing and art, music and art, design and art. This is kind of normal now, but back that it was like, “Wow, aren’t you cool.”

But it was starting to grow then. All of a sudden there were more art schools opening, and instead of being both grad and undergrad all of these schools were turning into just grad programs. Tons of people were moving to L.A., and it had always been a pretty good place to study art, but now people began to stay—it became a big scene. It just grew and grew and grew, and now it’s gigantic.

What did you think you could bring to the table through China Art Objects?

Because of the downturn in the art economy, even through there were all these new art schools opening there weren’t any new galleries opening up. At least there were no professional, white-walled galleries that were opening up—there were people who were showing in their apartment, because they could afford it, and there were weird little spaces that people would rent for a month or two. I guess Mark Grotjahn and Brent Petersen opened a space [Room 702] and had it for a year or so. But there wasn’t really anything that, for lack of a better term, took itself seriously. We wanted our gallery to look really good and to be professional. It was a challenge, because at that point I was still working at Art Center for another year and a half.

The gallery space before they rented it

The gallery space before they rented it

So why did you choose to open in Chinatown?

Well, we were looking around downtown, and we wanted it to be on the Eastside because most galleries were on the Westside but all the artists were on the East, and we lived on the East. We wanted to be pro-artist. What happened was that there used to be these two or three punk rock clubs in Chinatown that I could go to see music at, so me and a friend had gone down there to have lunch and walk down memory lane, and afterwards we strolled down Chung King Road, which was this pedestrian alley, and there were just all these places for rent. I called up Giovanni and said, “You’ve got to come down here right now,” and he did because we lived pretty close, and we just called up the first one that we saw.

It was $500 for a basement with this little loft upstairs, so we asked the others [Kim, Yao, and Heffernan] who had been kind of interested when we had talked to them and said, “We’re really going to do it. Are you really going to do it too?” They all said yes. So we built it out ourselves, and we had just enough money to do it. It took a long time—about nine months—but we threw a couple parties before it opened, so there was already a buzz among the artists at the school, who came to the parties and even rented out spaces next door to use as their studios. In fact, by the time we opened there were already two or three other galleries there that were about to open. Instantly, within two months, there was a little cluster of galleries.

Where did the gallery’s name come from?

That was from a sign that was on the original building when we rented it, and we couldn’t come up with another name—I mean, “Intra Hanson Yao Kim Heffernan”… it would just be nuts. So, actually, I think it was Stephen Prina who said, “You should just keep that name—it’s a great name.” And it’s got that double plural, which is silly: “China Art Objects Galleries.” We thought that was hilarious. And it’s a very beautiful sign, in red, white, and blue—it kind of looks like an Artforum cover from the ‘60s. It’s super Ruscha, that typeset and everything. We couldn’t have designed it better.

An opening at the gallery

An opening at the gallery

What does it mean that the artist Pae White designed your gallery?

Pae is an old friend of mine, she went to Art Center. She chose the colors, so there was a yellow kitchen and a grandpa-green loft space upstairs, and she decided to put globe lights in instead of fluorescents or whatever—which was really great because it flooded the walls evenly, so no artist could say, “Switch this light here or there,” because it would always be the same lighting. It made things much easier for us. She then put a wall here and, a lantern there. It was a really small space, so the more features it had, the better.

What was the first show?

The first show was really just showing off Pae’s space, but Pae and I had done some collaborative work together—these little architectural models made out of weird things—so we made a model of the gallery out of an aquarium. So it was mostly Pae’s show, but because we had designed that aquarium together my name was on it too—even though I usually don’t like it when dealers show their own art. Then we followed this with Sharon Lockhart and George Porcari, then Jorge Pardo and Bob Weber.

Pae White and Steve Hanson's aquarium model of the gallery

Pae White and Steve Hanson's aquarium model of the gallery

From the beginning, you seem to have gravitated toward doing two-person shows. Why is that?

Yeah, we did a lot of two-person shows [laughs]. I don’t really know why. With Sharon Lockhart, her career was already starting and she had a gallery in Germany, so she was already something of an “it” girl, and I don’t know if it was politics with her gallery, but it was her idea. George Porcari had worked in the library at Art Center too—I think he still does—and she was just a really big fan of his photography and wanted to champion him. With Jorge Pardo, he was showing the work of his roommate, Bob Weber, with whom he had collaborated for a long time and who had died a few years before, so it was a homage to him. I called them Braque and Picasso, because they both worked with furniture and design and lamps and things and informed each other.

Why did you decide to continue with the two-person format? Was it because you had the bifurcated space, with the loft upstairs?

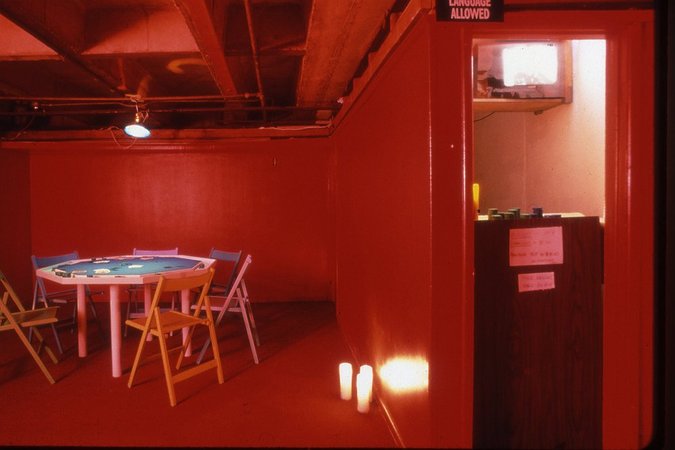

It wasn’t really a planned thing, it just happened a lot. But it probably had to do with the fact that collaborating was just something that was cool at that moment, with music-and-art crossovers and everything. So while some were two-person shows, some where straight-up collaborations, like Scott Reeder and Laura Owens’s “Heaven & Hell,” where there were light paintings upstairs and dark paintings downstairs, and there was this poker table that they made and videos. It was all over the place.

So what shaped your program? From the beginning you had a bunch of outside-the-mainstream sculptors and installation artists like Eric Wesley, Jon Pylypchuk, Sarah Braman, and Stephen Prina, while at the same time you had these unconventional painters like David Korty, Bjorn Copeland, Katherine Bernhardt, Kim Fischer, and Sean Landers. How did your interests get channeled through these choices?

I don’t really know. Why do you like what you like? I mean, a lot of it was because there were five of us in the beginning, so it was all of our opinions. But at first it was mainly that we knew some people who were doing well and we wanted to get noticed, so we kind of rode on those artists’ coattails. Then we would also show people who were still in school or who were just getting out of school, and those were a little more our style. Like, Sharon Lockhart was definitely a friend but she was not necessarily my style or someone who I would show personally—I think Giovanni liked her and she liked him and they wanted to do something. A lot of the time people like Frances Stark would come and ask us to do a show, and then we would go and ask the people who were coming out of school, because they didn’t have the wherewithal to ask us.

A room in the 1999 Laura Owens and Scott Reeder show

A room in the 1999 Laura Owens and Scott Reeder show

Who were some of those more up-and-coming artists you discovered?

I liked Eric Wesley and Jon Pylypchuk and David Korty and Ruby Neri. We also did a show with Christiana Glidden, but then she moved to Germany and I don’t think she’s doing anything with art anymore.

What kinds of precedents or templates did you look to for inspiration? Were there any galleries that you were thinking about?

Well, Giovanni had had an artist-run space in New Zealand, so he just said, “Yeah, we can do it.” But in New Zealand you have state funding—you just have to pay your rent and then you can get welfare money. But I guess we were just inspired by all those galleries that were popping up in apartments. 1301PE was in Brian Butler’s apartment, and a lot of my friends were showing there, and he was young and doing really interesting things. Another one that was really cool was Bliss gallery, which was Ken Riddle, and Jorge Pardo collaborated a lot with him.

Then there were also these weird galleries that were appearing and tying to show people, like Shoshana Wayne, and, I don’t know, they just didn’t feel right. So we just thought we should do it ourselves, somehow, and that we would up the ante, and our apartments were too small anyway. And I had always had the idea of starting a gallery or something—maybe a school or a retreat somewhere. But Giovanni really catalyzed my efforts.

Eventually the others peeled off and left you and Giovanni. He was a writer and a Fulbright scholar, is that correct?

He was an art critic, and we even before he graduated he was writing for places like Artforum. There was another magazine in L.A. called Art and Text that he did a lot of writing for, and it was kind of like our gallery–it should have been a scrappy fanzine but it was super polished and really beautiful, with color prints, and mostly just about the L.A. scene. It looked great, and if your gallery got a review there it was kind of a big deal. I guess it was a bit of a conflict of interest that Giovanni was writing for it, but he never wrote about our shows, though he might write about artists we were trying to show. So it was a conflict of interest, but it’s fine—it was small.

Giovanni Intra

Giovanni Intra

How did you meet him?

He worked in the library too—there were a lot of people who worked there—but I actually first met him at one of those Moontribe desert parties, which are really ridiculous when you talk about it, but were really stupid fun. I just saw him and recognized him and we were like, “You’re crazy!” “No, you’re crazy!” And that was it. We met at work the next Monday and were tight from then on.

What was Giovanni like as a person?

He was just super charming, and very ambitious. He was a really good cook—he would invite people over to his studio apartment and cook for them. And he was a super flirt. He went out with lots of people. He made you feel like you were special somehow, like you were the only person he was thinking of. Actually, Tuesday went out with him for a month or two, and I met her through him. I was already married at the time so it wasn’t like I was in love with her instantly, but I was like, “Your girlfriend’s cool.” Then they broke up and I didn’t see her for seven years.

So she was the one who said what a good flirt he was, but I also saw it in action lots of times. For me, as his friend, it was like watching this new voice come over him, and he would suddenly start to shine. It was kind of gross if you saw it too many times [laughs]. But I saw its effect, and it was pretty good.

How did you two decide to divide up the responsibilities in the gallery?

It was always a little tough. One person would get his way and the other person would pout. But it worked because he was like a brother—emotions would heat up and we would both figure out how to apologize that day and hug and do our thing. And because we still had our jobs we would divide things up so that he would have the gallery on Wednesday and Thursdays and I would have it on Tuesdays and Fridays and we would both have Saturdays, which is when most people would come by. Your responsibility was whatever happened on your day.

The China Art Projects office

The China Art Projects office

How did you start to gin up the kind of collector interest that could lead to sales?

Well, everyone was all in the same art scene, and when artists talk about things, collectors listen. By the time we had the Laura Owens show she was already a darling of the art scene, so a lot of collectors listened to her. And Jorge Pardo, Pae White, and Sharon Lockhart were doing a lot of touring around Europe, doing shows, and they were talking us up as the cool new gallery—and because they were in Europe at the right time, the galleries there thought that we were better than we were, and they started inviting us to fairs. Normally you have to apply to these things, but they started inviting us. Liste was the first fair that we did, in 2000.

So, it was mainly because I had all these older artist friends from Art Center who were doing really well, but Giovanni also had a lot of writer friends, so we had this group of established people who would go around and talk about this new space that was open. All the while, we were waving the flag pretty hard that we were there.

The Jorge Pardo and Bob Weber show

The Jorge Pardo and Bob Weber show

Who were your biggest early collectors?

Dean Valentine was really the first to find us, and then he told all of his friends, because he was a mentor to all these people. I think he came in though Laura Owens, actually. Another important L.A. person from the ‘90s was Tim Neuger of Neugerriemschneider in Berlin. He was in his twenties and worked at a gallery in Santa Monica that Luhring Augustine supported, and he had a big L.A. network and was doing some cheerleading for us as well.

And it wasn’t just a gallery—you had a record library in the basement? What kind of audience did you draw?

Yeah, that was an Amy Yao thing. She was on Kill Rock Stars, so she knew all these Olympia music people, who I wish we had taken more advantage of. She was only there for about two months before leaving, but she was an important part of the gallery. Anyway, after a while Chinatown became this thing—it got bigger than most of the galleries even wanted it to get, because people started coming down to drink free beer and pick up girls. Somehow the word got out, and at a certain point you would be walking down the street and there would be these xylophone people set up and jugglers. At the time it was like, “This is annoying,” but looking back on it now, wow—it was like we were putting on this homemade circus that would pop up every month.

When did you know that the gallery was a success?

I think Giovanni said it to me—because at the time I was still working at the library. At that point we had done maybe two art fairs and he said, “We can do this, but you’re going to have to quit your job.” Before that, even kicking in $100 for a can of paint would have been a big deal if I didn’t have my job. So I was like, “Okay, let’s just do this.”

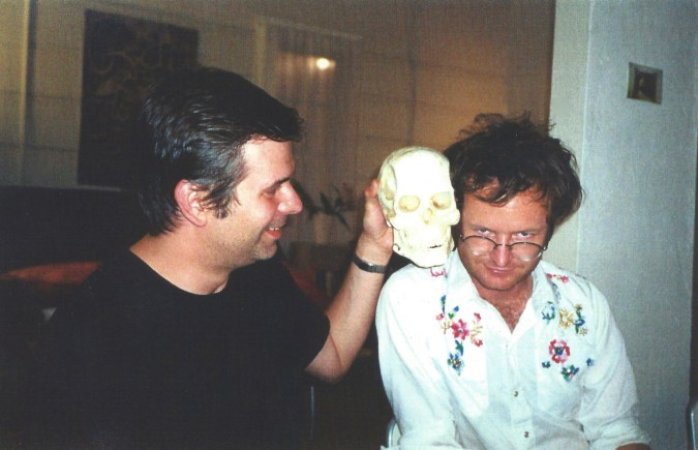

In 2002, a tragedy struck the gallery when Giovanni died. He was 34. What happened?

It was very terrible. It was a really bad year for me, too, because my mother died, and I had a baby—which wasn’t terrible, but a big change—and the war was starting and I had to move. But what happened was that Giovanni was in New York for Eric Wesley’s opening at Metro Pictures. He had just finished doing Art Basel Miami Beach, which was the first edition of the fair, and he was staying with a friend from New Zealand who was a heroin addict and a pot dealer.

We had gone out there a couple of times and he and Giovanni would take the heroin and smoke it and me and some artist would smoke the pot and it was all very casual—you could tell that he was really good friends with this guy, who was super smart. It was just a really good time, like going to the bar and getting drunk, except it can kill you. According to the doctor Giovanni had an enlarged heart, which I think is because he had gone to Miami and drank a lot and didn’t sleep enough. It was exhaustion combined with the wrong drug at the wrong time.

How did you hear about his death?

After the Eric Wesley opening, everyone went to Gavin Brown’s bar, Passerby, and things got wild—they got kicked out and there all these were cops. So all the next day I was getting calls from Gavin Brown, and I was like, “Oh shit, I’m about to have this baby, I don’t want to have Gavin Brown yelling at me for Eric Wesley doing something at Passerby.” But then someone told me, “You better talk to him—you better take the call.” And it was Gavin Brown who told me that Giovanni died. I remember taking that call. It was a very kind thing that he did.

Probably the last picture of Giovanni Intra (Rob Pruitt at left)

Probably the last picture of Giovanni Intra (Rob Pruitt at left)

How did the gallery recover?

Things were already set up six or nine months in advance, so I didn’t have to worry about that too much. And we had our first assistant at the gallery, which helped. But it wasn’t like there was panic, like it was a sinking ship and everyone was like, “Let’s get out of here.” All the artists were still behind me, and the Chinatown scene was still strong. David Kordansky opened a few months after, and all of a sudden Chinatown had this second wave. So it didn’t really did have an effect on the gallery, except of course that everyone would talk about it. Not to glorify anything, but it was kind of this rock-n-roll scene at the time—like, “L.A. is crazy.”

Then you added some fuel to the fire by opening Mountain Bar in 2002. What happened there?

[Laughs] That just came out of me and Jorge walking around Chinatown—a lot of the inception of the gallery was just walking around Chinatown and daydreaming about what we could create there. So, Hop Louie was a bar there that everyone went to—it became the cool artist watering hole—and one day I went in there with Jorge to have a drink and he said, “You know, this bar is making a lot more money than the gallery is—we should just open up a bar.”

So we did, but we never really made money. It was a cheap space but it was too big so you always had to host these big clubs that weren’t from the art scene, and you had to charge too much for the drinks just because of the overhead. I mean, it wasn’t a disaster, but it wasn’t great. At the beginning I wanted to do it because, you know, community! It will be great for all! But in the end it was a big ugh. Even I would go over to Hop Louie instead to have beers with people.

What was a typical night like at Mountain Bar?

A typical night at Mountain Bar would be pretty empty [laughs]. Chinatown without an opening doesn’t really have much going on.

What was an extraordinary night at the bar like?

Usually they would be after the shows. But really, Chiantown at that time was like a meerkat warren. All through the night different people would have their places open, so you would sort of travel from this basement to that studio to that bar to that basement. Few nights stayed in one place. Joel Mesler was doing some fun things, actually. He rented a space on the roof of the building next door—there was just this weird little turret—and he had all these shitty instruments up there, like a bass with three strings and an out-of-tune banjo and a drum kit that had things missing from it. So people would be at the bar and say, “Let’s go up to Joel’s!” We’d grab a six pack and go up there and play music and smoke pot and it was super fun. The music was just awful—people would be jamming who had no idea how to play music and didn’t care. But it was the place to be, and right outside there was this really beautiful view of Los Angeles. So that made for some epic nights.

Mountain Bar

Mountain Bar

How long did Mountain Bar last for?

It lasted for like five or six years. Then the economy went down and the whole Chinatown scene fell apart. Peres Projects and Kordansky moved to Culver City and [Joel Mesler’s] Pruess Press closed up shop for a little while, and everything was just really slowing down, so even the big after-opening events became a little lackluster. And then the police started cracking down—they just started picking on us. A couple undercover cops would come in and start dancing, because we didn’t have a dancing license, and if the bartender didn’t tell them to stop they would write us up. Another time they came and asked, “Do you have a happy hour here?” and the bartender said, “Sure, I’ll give you a dollar off.” But because we weren’t allowed to have happy hours, they wrote us up. And all of a sudden we had to have three security guards on a Tuesday night when there were two people in the place. We just decided, we can’t do this.

In 2010 you moved to Culver City as part of this general exodus from Chinatown. Why did Culver City become the place to be?

Well, it began when Blum & Poe opened a big space. It wasn’t cheaper in Culver City, but you could get bigger spaces there, and a lot of artists just wanted bigger and better spaces to show—Chinatown had really small spaces. It got to the point where artists wanted more, and if you wanted to keep up and be professional you had to grow.

How has the gallery evolved and changed in its current incarnation?

The space is bigger and nicer, so people can put on bigger and nicer shows. We don’t have the globe lights, so we have to get on a ladder and change the lights for each show. We have storage. We still have the same color scheme, though, and the globe lights are outside, and we still have the old original sign out in the foyer. It still looks like China Art Objects.

When did it become profitable?

I don’t know if it ever did [laughs]. It’s not like we’re Gagosian or Zwirner or anything. We’re just plugging along, doing our thing. What is profitable? I would say there are still some tight squeezes. Especially in the summertime it’s like, whoa, because you put on one show over four months but you still have to pay your rent. Running your own business is pleasurable and awful at the same time. Feast and famine.

What do you make of the L.A. scene when you look around yourself now?

It’s tough to tell. It’s just mushrooming right now. People from New York are moving in, and lots of people are opening up galleries. There are still people doing apartment things but there are also people making these really nice-looking spaces, and you don’t know how serious they are. Speculators seem to be thinking this is a really great place to make a lot of money. So I don’t know how it’s going to work out. It’s always good to have a lot of energy, though.

The new China Art Objects gallery

The new China Art Objects gallery

What do you make of the whole L.A. flipper culture, with Stefan Simchowitz and Art Rank?

I think it already existed before they arrived. The Rubells basically do the same thing as Simchowitz—he buys in bulk, cheap, and when the market hits he takes credit for it. I think this has been going on for a century, really. In any case, I haven’t really been Simchowitzed yet. With us he really acts like a consultant—he brings people in and says, “This is the best thing ever.” Then he wants a little percentage as a consultant, and he usually trades that in for art.

So for us he’s not a monster, but I’ve seen him be a monster, buying a lot of art from an artist and then saying, “I need more to do anything for him” And it’s like, wow, that artist gave you all this stuff for nothing, basically. But it’s good for some people. The whole art thing is really weird right now, and I’m not sure how it’s going to land. Simchowitz says the whole gallery system is dead, but there are so many new galleries opening up. It’s amazing how many New York galleries are opening out here, for some reason.

Why do you think that is? L.A. used to be knows as a collector wasteland.

I think it still is. My take on it—and other dealers have agreed—is that artists want to do shows in L.A., but the galleries out here don’t invite enough New York or European artists. Maybe it’s because you have to fly all their stuff out here and pay consignments and then no one buys it and you have to ship it back. So I guess if you’re a New York gallery and one of your artists wants to do a show in L.A. you can just come out here and have these walls for cheap and then pre-sell it with your collectors in New York. It sounds like a pretty good model.

But why do the artists want to show in L.A.?

I don’t know. That’s the thing I’ve never been able to figure out. Maybe because it’s warm? It’s a nice scene out here. You know, Michele Maccarone had a space out here before about eight or nine years ago—it was actually the space that we’re in now. Me being cynical, it’s maybe just that these galleries have a lot of money.

Is there still a sense of community in the art scene out there?

Yeah, each neighborhood has its community, probably. You know, artists always have their friends. And the scene is mushrooming out. But it can’t be the same thing. You know, back in the ‘90s you could go to one bar and there would be 100 people in there and that was the entire art scene. It felt like a cool little secret, but when something gets this big there’s no secret anymore. There’s no cool club. It’s just a bunch of interesting people doing things. But yeah, I think it’s good.