The photographer Catherine Opie emerged during the era of the culture wars with searing, confrontational portraits and self-portraits—works that simultaneously asserted queer identity, aspirational American domesticity, and membership in the art-historical fraternity of Holbein, Bronzino, et. al.. In one of her best-known works, Self-Portrait / Cutting (1993), Opie turned away from the camera to reveal a childlike image of a house and a stick-figure couple that had been carved into the skin of her upper back. Behind her was a rich background of green brocade, reminiscent of the one in Holbein's Portrait of Thomas Cromwell .

Since then she has taken the occasional detour from studio portraiture into cityscapes and landscapes, documenting the architecture of freeway underpasses in Los Angeles (where she teaches at

UCLA

and shows at

Regen Projects

) and capturing sporty, all-American tribes of surfers, ice-fishers, and football players in various regions of the country. Yet her art has remained centered on the body—the communal body, if not always the individual one. Opie's most recent work, which will be seen in January on both coasts—at

Lehmann Maupin

in New York and at the

Hammer Museum

and

MOCA Pacific Design Center

in L.A.—includes portraits of

such artist friends as

Kara Walker

and

John Baldessari

, as well as a series on

Elizabeth Taylor

's home that's modeled on

William Eggleston

's haunting images of Graceland.

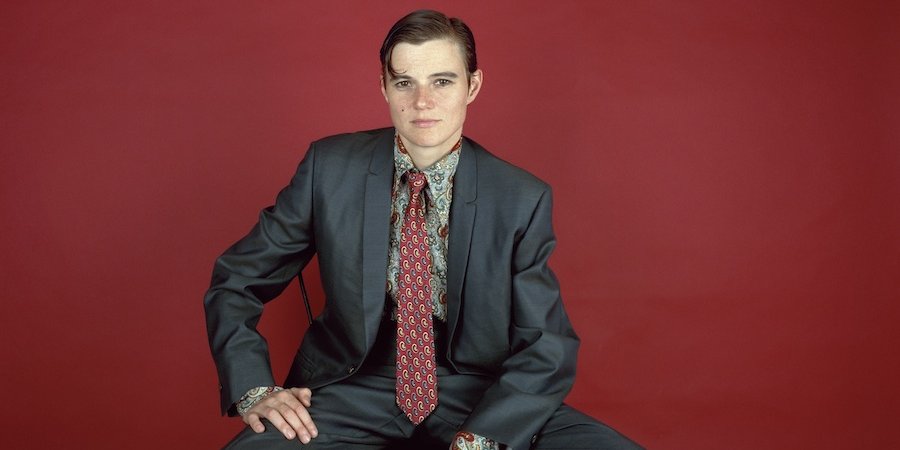

On the occasion of the release of Phaidon 's Body of Art , which includes Opie's photograph Angelina Scheirl (pictured above), the artist spoke to Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg about the works that have shaped her vision of the body.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Art and buy the book.

MOAI OF RAPA NUI

Artist Unknown, c. 1100-1650

Body of Art has this huge scope—it goes back almost to the beginning of where we think about art. The impression I got from the entire book was the idea that art is utterly entwined with the human experience. I always liked the Easter Island statues—they are so mysterious to me. I’ve been following the excavation of the torsos of these statues in Smithsonian magazine. It’s like, wow, they’re not just heads—there’s a whole body there!

HENRY VIII OF ENGLAND

Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1537

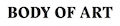

Catherine Opie's Self-Portrait / Pervert, 1994. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

Body of Art paired my Angelina Scheirl next to an Egon Schiele, who is one of my favorite artists of all time in terms of portraiture. But I was actually thinking about Holbein. A lot of my early portraits were really in relationship to Holbein, who tried to ask and answer the question: How can a portrait hold you through time? When I made Pervert , I was thinking about Holbein’s Henry VIII . Pervert ended up being kind of my own Henry VIII moment. His use of color, as well as the gaze, influenced that body of work tremendously.

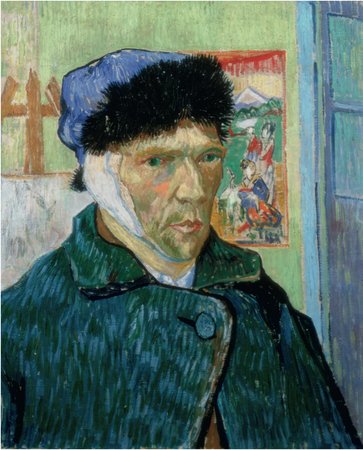

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH BANDAGED EAR

Vincent van Gogh, 1889

The van Gogh self-portrait in Body of Art is so interesting because it reveals a lot of what was going on in that time period, with van Gogh and representation, but it also holds back. I love the way the jacket is painted, and that he has his hat on indoors—or maybe he’s at an outdoor café. There’s the incredible vulnerability of him painting himself when he wasn’t in his full mental faculties. There are just a lot of questions. And then the gaze is also what I do within my own portraits—it’s not looking at you or looking out, it’s looking off to the side. It gives you permission to stare.

LEWIS HINE (Various Works)

(Below:

Addie Card 12 years. Spinner in North Pownal Cotton Mill.

Vt.

, 1910)

Lewis Hine had a huge influence on me, in terms of the idea that social documentary could create a visibility that changed laws. [His work as the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee was instrumental in turning public opinion against the practice.] Not that I went out to try to change laws, but I certainly was working on issues of representation and visibility within the queer community, and I was making that work in the ‘90s.

"PEOPLE OF THE 20TH CENTURY" (SERIES)

August Sander, early 1920s-1964

(Below:

Circus People

, 1930)

August Sander has been utterly important as a portraitist, in terms of his ideas of typology. But I actually wanted to go against typology in my own work. I mean, what Sander did is important, but it was a very different kind of archival project: the citizens of the 20 th century. I wasn’t trying to map out queer identity in the broader scope of that kind of archive—I was trying to make really good, meaningful portraits at a time when a lot of my friends were dying of AIDS. My works are much more emotional—there’s nothing neutral about my portraits.

THE LADY WITH AN ERMINE

Leonardo da Vinci, 1489-90

Catherine Opie's Oliver & Mrs. Nibbles , 2012. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

These works are definitely still about documenting a community, but they’re coming from a more internal place. The figure is emerging from black because it’s emerging from my own mind or my own state. It’s very Caravaggio, very da Vinci— Oliver & Mrs. Nibbles is very much modeled after da Vinci’s portrait of the girl in the ermine. I’m going back into that place of painting as a religious experience. Why do we get held by those paintings? Why is there a line outside the National Portrait Gallery in London that queues up for hours to see the da Vincis? It has a lot to do with the kind of questions I’m asking about photography right now—I think photography is in a really hard place, in terms of social media and our image-saturated culture. This new body of work asks the viewer to be held again, for longer than the moment of an image flowing through your stream on Facebook.

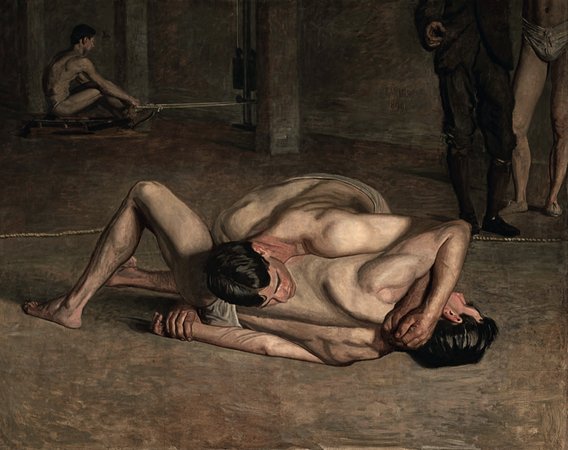

WRESTLERS

Thomas Eakins, 1899

I’m crazy about Eakins. In fact, LACMA paired an exhibition of mine with a show of Eakins. I especially love the use of red in Eakins—if you really dig into his work, the red is so incredible. He uses it in a realistic situation, where you almost believe that the red is there at that moment—the person on the boat has a red shirt on, or the boat is red. But it’s more about where he’s trying to lead your eye within the canvas.

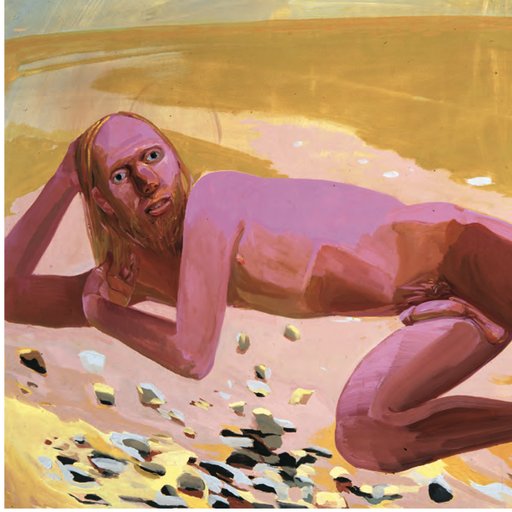

LANDSCAPES

Justine Kurland

's

Orchard

, 1999 (top);

Andreas Gursky's

Pyongyang V.

, 2007 (bottom)

Justine Kurland

's

Orchard

, 1999 (top);

Andreas Gursky's

Pyongyang V.

, 2007 (bottom)

Justine Kurland is someone who really looks at the history of the figure in the landscape. I really appreciate the depth and the mythos behind her work. It’s the same with early Gursky, before he really started manipulating the landscape. When you look at the figure in space, with early-'90s Gursky, it’s fascinating to think about. You have this vast space, and then these tiny figures. What he was trying to do is really accomplished.

THE LAST TIME EMMETT MODELED NUDE

Sally Mann

, 1987

Sally Mann’s imagery of her immediate family brings you into this totally intimate moment. I love her photograph of the last time her son Emmett allowed her to photograph him nude. He’s standing in the river, and I love the gaze back at the camera and the exposure and the movement of the water. It’s just such a beautiful photograph—I can look at it forever.

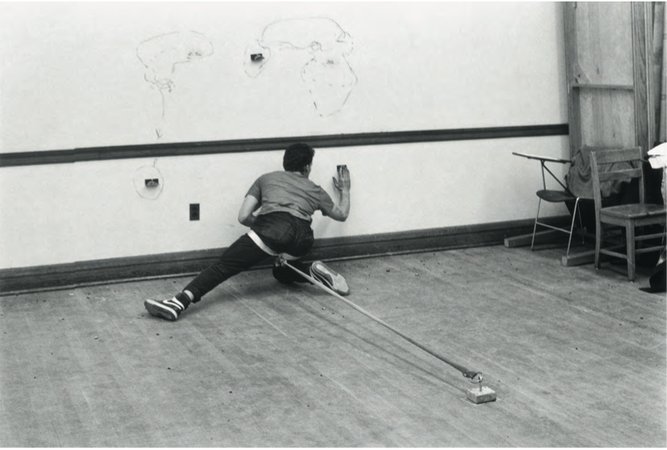

Matthew Barney

's

Drawing Restraint 5

, 1989 (top);

Cindy Sherman

's

Untitled # 216

, 1989 (bottom)

Matthew Barney

's

Drawing Restraint 5

, 1989 (top);

Cindy Sherman

's

Untitled # 216

, 1989 (bottom)

I feel really fortunate that I’ve been able to be an artist in my time period, because of the conversations my contemporaries and I been having with each other for the last 30 years. Last night I was having dinner with Matthew Barney, who works with an incredible degree of specificity but also pushes all these other boundaries. And the influence of Pictures Generation artists like Cindy Sherman is huge. We’ve been talking about all of this for years.