In Phaidon's new Catherine Opie book , the curator Helen Molesworth writes that “I’d like to think that if I lived in the future, I could be a connoisseur of a Catherine Opie photograph.”

What does she mean? Well, “connoisseurs were not simply the people who could identify the finer things in life,” she explains, “they were people who knew enough to say, ‘I think that might be a Caravaggio,’ and possessed the skills to back up that sort of claim.”

So how would Molesworth spot an Opie original, and how would she back up the claim? Again, she elaborates: “I’ve been looking at her pictures since the early 1990s, marveling at the desolate Los Angeles freeways, the blank stillness of the domestic exteriors of Southern California, the spooky emptiness of corporate America’s downtowns.”

“Then came the infinite landscapes," the curator writes, "reaching edge to edge in every photo, the ocean, the football field, the great lakes, each dotted with individuals, almost always rendered anonymous, in pursuit of a perfect wave, a touchdown, a fish. There was, in other words, the figure and the ground, the cosmic and the molecular, the empty and the full.”

The empty and the full, the figure and the land mass, the outsider and his or her group, who, in turn, make up the patchwork of American society. Is this what sets Opie apart?

Here, the LA-based fine art photographer discusses two very different works that lie at either end of this signature continuum, which nevertheless, seem to be reconciled in quite similar artistic outcomes. Both are launched today as Phaidon collector's edition prints.

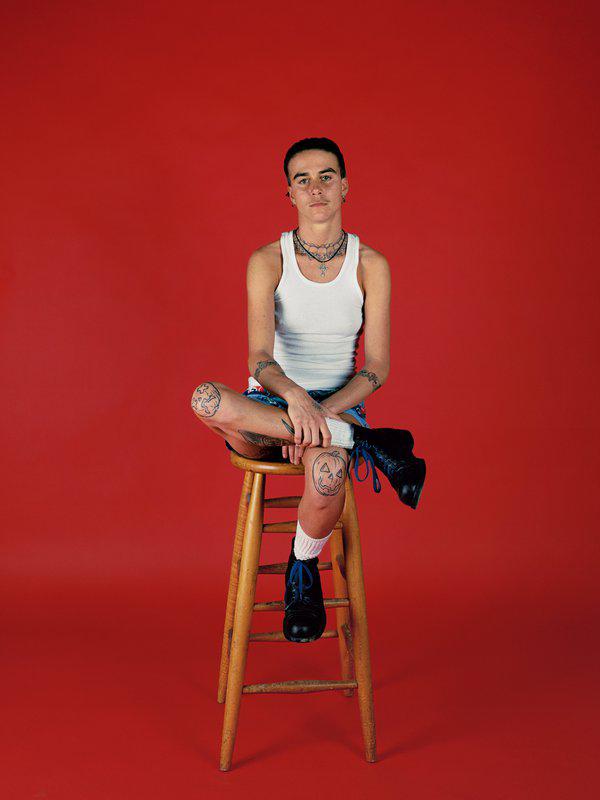

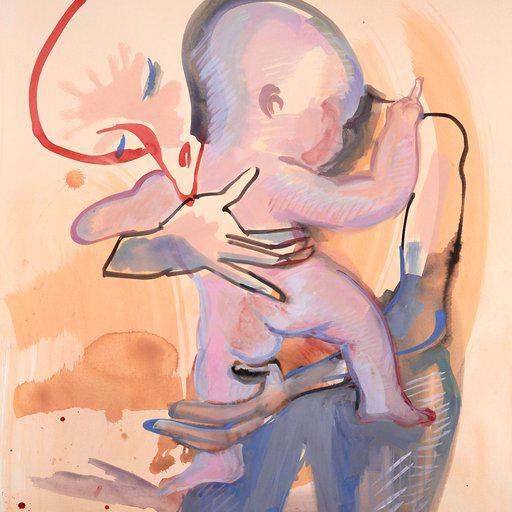

There’s her portrait of her friend and long-standing subject and collaborator, Pigpen. The pair have known each other and pretty much been pals for as long as Opie has been photographing seriously. Pigpen appears in Opie's first film, The Modernist, which follows Pig Pen as they set fire to modernist architectural icons in Los Angeles: the angular Sheats-Goldstein Residence and the Chemosphere. After these torchings, Pig Pen creates collages that commemorate their crimes.

'Muse’ is the wrong word to describe this relationship, as Opie explains; the strength of friendship is more important, as is the passing of time that enables her to watch her friend’s body change, and feel their bond deepen.

Opie can’t quite say the same thing about the world-famous beauty spot which is the subject of the other edition. Of course, the falls in the image are beautiful and familiar, but can a photograph still capture that beauty, once it’s been shot and shared, over the decades?

In this instance, Opie feels that our own cellphones get in the way. When people visit America’s national parks, they reach for their phones, rather than allow the “quietness to seep in,” she says. Instead, her near-abstract, almost baroque take on the waterfalls raises the possibility that a landscape image such as this can hold the viewer for a moment, enabling them to enter into a deeper and longer lasting relationship with the scene than any cell phone would ever allow.

Read on to discover how these ideas of depth, emptiness, friendship and familiarity play out in these two genuine, and genuinely moving, Opie works. When we chatted Opie was nearing the end of a series of photographs created in the Vatican, Rome. We'll be carrying a larger interview based around that work, her photographic response to the pandemic, and much more, next week. For now though, here she is talking about the two limited editions launched today.

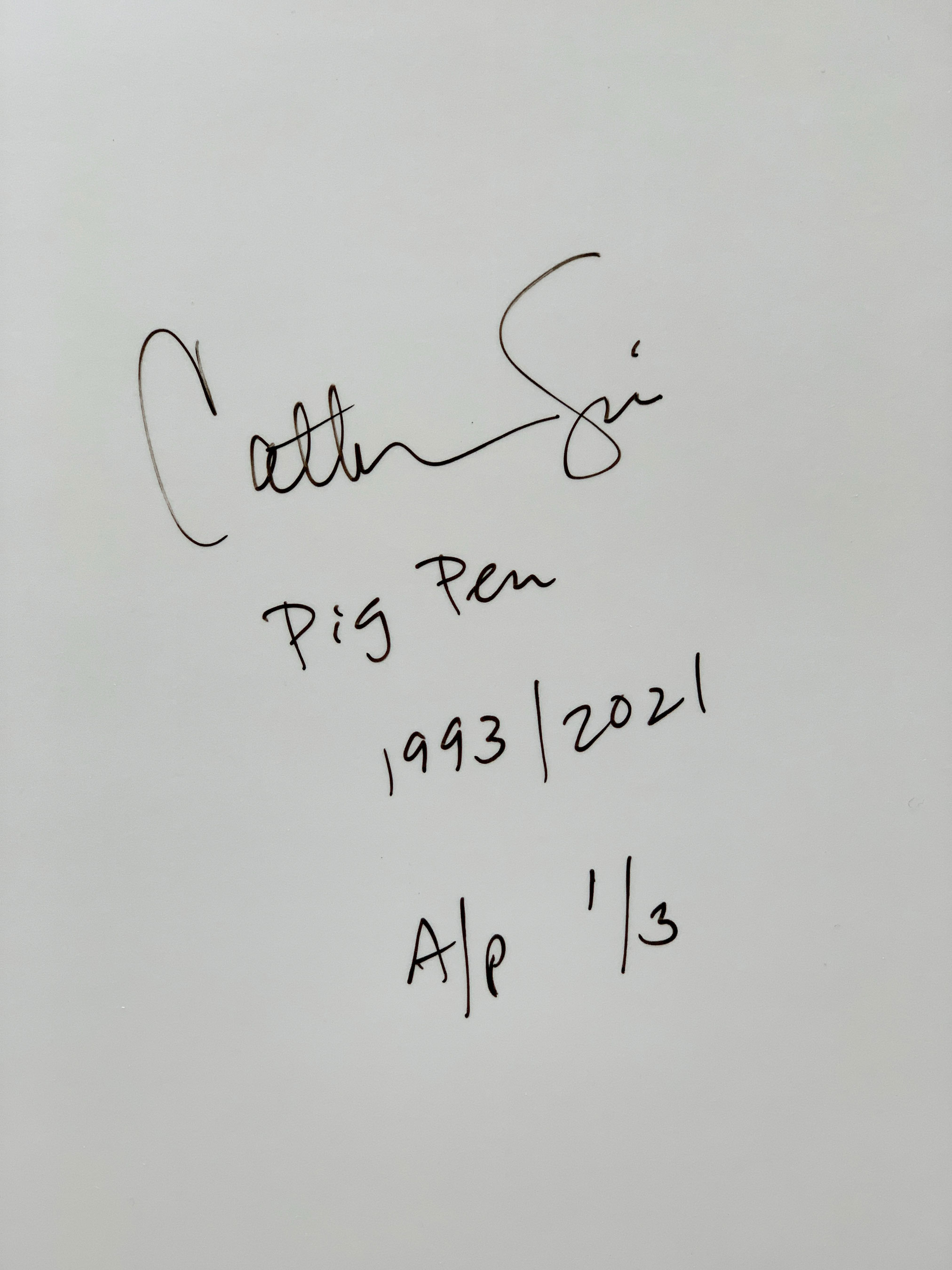

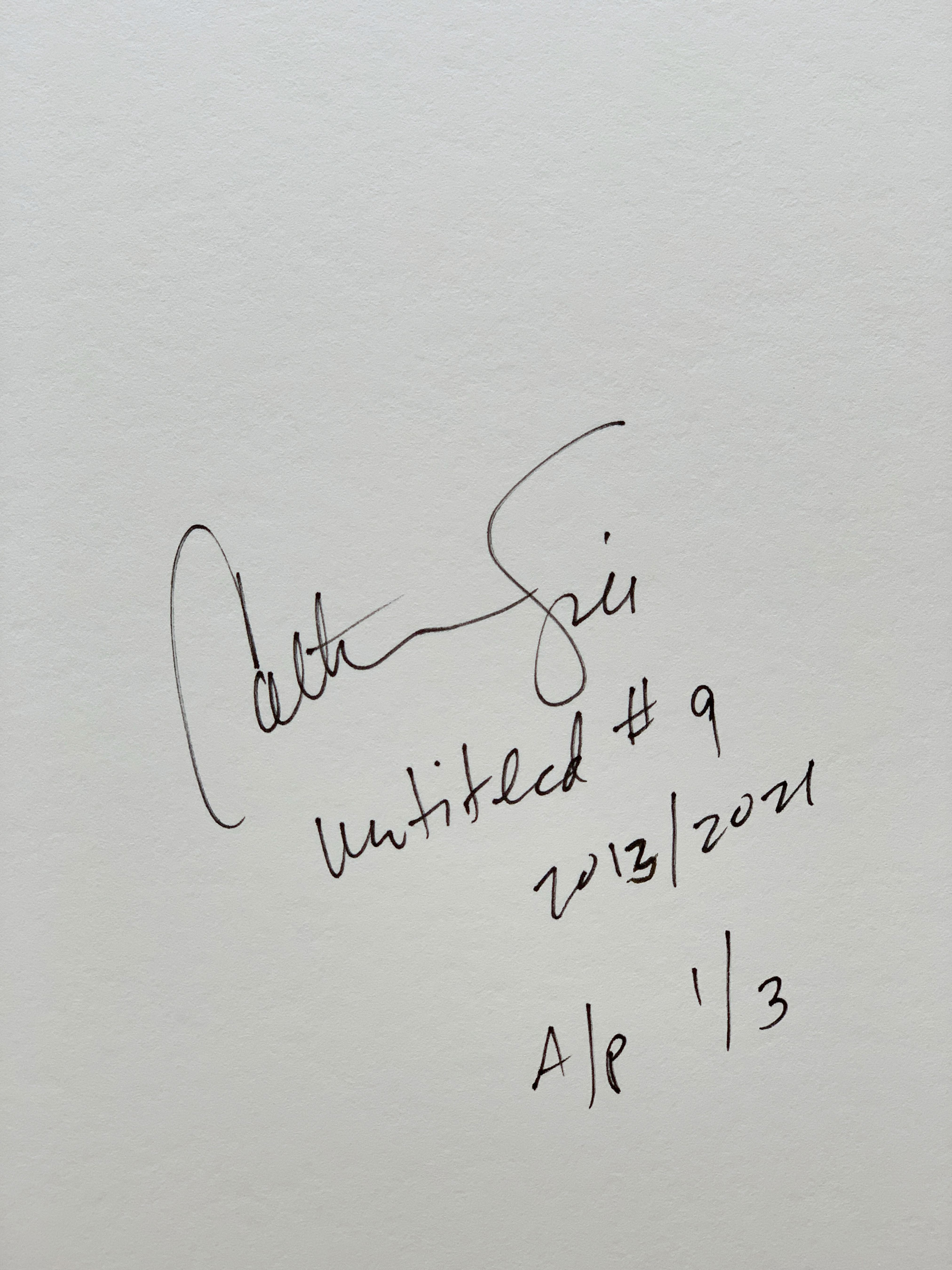

PRINT OPTION 1: Pig Pen, 1993/2021 Pigment print on Moab Slickrock Metallic Pearl paper Image size: 12 ¼ × 9 in. (31.1 × 23.4 cm) Paper size: 12 ¾ × 10 ⅞ in. (32.4 × 27.6 cm) Edition of 5 + 3 APs Signed and numbered by the Artist on reverse $2,800 unframed PRINT OPTION 2: Untitled #9, 2013/2021 Pigment print on Hahnemühle Fine Art Pearl paper Image size: 8 1∕6 × 12 ¼ in. (20.7 × 31.1 cm) Paper size: 10 ⅞ × 12 ¾ in. (27.6 × 32.4 cm) Edition of 5 + 3 APs Signed and numbered by the Artist on reverse $2,800 unframed

I’m very careful in that people I photograph a lot - in my opinion they’re not my muses. I’m not interested in artist muses I think it takes away from the person.

Pigpen has always just been one of the most interesting friends in my life - a very, very tender and strong personality in a way that is just about kindness and humanity. Also, well, quite frankly, I like to look at Pigpen!

Is it the face or the mind I’m interested in? I think it’s both. I think that I like both. It’s not just about the exterior. With my friends’ bodies the amazing thing is that they’ve changed so much through the years and through long and continuing relationships. You see the marks on the body and the history of that change. I just think that’s really beautiful. I really do view the body as a site of architecture to a certain extent.

In the same way that here I’m looking at the Cathedral in Rome, and I suddenly realise, 'Oh yeah, they added this part for structure it’s not an original part. Or, ‘Oh they took out all the metal, that’s why the holes are there’.

I think that it’s about the tracing or tracking something through time. In some ways the continuing photographing of somebody like Pigpen through the last 30 years is also really acknowledging how deep those friendships truly are and how important they are, two people who really love each other as friends and care for each other. And so not only a friendship but a long friendship.

As you age you change, your body changes. 60 was a big number for me this year. I told everybody I wanted to die at 80 - that’s only 20 more years so I’ve got to maybe rethink this!

You get to watch the skin change around the face and, you know, Pigpen’s body has gone through some really interesting transitional things in terms of getting surgery and other things. And I think that in terms of how queer culture has changed to be, all of a sudden, accepted in a different way; but that how radicalised we were when we were young in terms of fighting AIDS, and being activists.

I also really like tracking that idea that the body is still within the conversation of counter-culture - or activism - in relationship to how time has changed and that I do have the right now to be married and so forth. I think it’s really important to remember those aspects of the body.

Normally when I make a portrait it’s like 45 minutes spent with someone; even though if it's Pigpen we might have dinner or share a bottle of wine or whatever. You spend 45 minutes with a person and you go back to them in different bodies of work because it’s important to them, it’s important that they continue being reflected upon.

You don’t want to 'overuse' somebody - like how I’ve never overused my son Oliver, even though I adore looking at him - but you want to acknowledge that these relationships exist within these series of portraits.

Pigpen is the protagonist that I picked for my film The Modernist - that is like really a portrait - it’s a story that I wrote. But the reason Pigpen was picked is because Pigpen would be the most convincing person in relationship to the story that I created in my head.

The Modernist was fantastic because it showed how well we knew each other. It just showed that in terms of my directing and my looking at Pigpen there was a different kind of love letter within that piece than within other portraits.

You could see how much there was a different feeling to it for me and also what Pigpen brought to it in terms of making the collage, and the studio.

Even though I was directing it, I would just simply say a few things to Pigpen and then Piggy would get it immediately and be just like, 'yeah I can do that.' It came alive where it was truly more of collaboration than I allowed my portraits. I don’t really allow much collaboration to happen in my portraits.

Catherine Opie - Untitled #9 (2013), 2021

PRINT OPTION 1: Pig Pen, 1993/2021 Pigment print on Moab Slickrock Metallic Pearl paper Image size: 12 ¼ × 9 in. (31.1 × 23.4 cm) Paper size: 12 ¾ × 10 ⅞ in. (32.4 × 27.6 cm) Edition of 5 + 3 APs Signed and numbered by the Artist on reverse $2,800 unframed PRINT OPTION 2: Untitled #9, 2013/2021 Pigment print on Hahnemühle Fine Art Pearl paper Image size: 8 1∕6 × 12 ¼ in. (20.7 × 31.1 cm) Paper size: 10 ⅞ × 12 ¾ in. (27.6 × 32.4 cm) Edition of 5 + 3 APs Signed and numbered by the Artist on reverse $2,800 unframed

Well do we want to say where this is? Because one of the nice things about abstract landscapes is they're abstract.

Part of why the body of work of National Parks is abstracted is because in the age of cell phones we are now just going to these places to click at them, not to ponder on them. We're not allowing the quietness to seep into us.

It has been driving me crazy how basically the cell phone has now become the experience. We have to put it on Instagram, we have to see the post. We have to see all of that and I’m asking people to slow back down. So by using those abstract photos of National Parks I’m actually asking people to pause for a moment and not let these places only exist as a tourist site.

In this image you recognise that I’m obviously in the history of baroque painting, but this isn’t a baroque painting. So it’s not that I’m trying to recreate those paintings. I’m just using lighting and the components to actually talk more about what it means to 'look' these days. And what it means to go into something deeply, and to be able to be held by it. I’m really interested in that word 'held'.

You don’t have to just click away, or swipe away; you actually need to be present with what is being shown to you. And you want to kind of almost escape to it. I use scale as well to then place the viewer within this landscape.

The reason why they’re untitled is to help you find your place in the place. Can you find what these places actually mean? And also, it's about the preservation of that. And that’s what I wanted them to do, so I am very happy when people tell me they actually do that.

It’s really funny because that body of work drives my mom crazy. Why? 'Cos it’s out of focus!' she says. 'I know mom! That's the point!' And she’s like, ‘I don’t like it! It bothers my eyes to look at it!

The new photos of swamps I’ve been doing, those are not out of focus, because the ideas around rhetorical landscape needed to have the swamp be as pristine and as beautiful as swamps are. Because those are also disappearing.

The new photos of swamps I’ve been doing, those are not out of focus, because the ideas around rhetorical landscape needed to have the swamp be as pristine and as beautiful as swamps are. Because those are also disappearing.

So with these photos, I'm asking us to contemplate, quite honestly, what’s happening to our world, and to our earth. The big thing about the pandemic is obviously the fact that we lost so many people but maybe as people we have to decide how to recalibrate our lives a little bit when the pandemic ends.

I don’t really want to add to the larger carbon footprint. I don't want to be on a plane every month. Julie and I tried very hard in the middle of LA to make our house as sustainable as possible. I don’t know how to represent that in photographs but I can make an abstract that maybe will allow you to meditate on what we have, and maybe that meditation is good enough.

You can find out more and enquire about

the edition here

. Look out for out extended Catherine Opie interview next week in which she talks about the body of work that she's currently shooting in the Vatican, her photographic response to the pandemic, and her life in fine art photography. Meanwhile, take a look at

Phaidon's new Catherine Opie book here.

Phaidon's Catherine Opie special edition book with both of the prints. Hardcover 10 7⁄8 × 12 3⁄4 inches 338 pages with 6 gatefolds 300 duotone & color illustrations

Phaidon's Catherine Opie special edition book with both of the prints. Hardcover 10 7⁄8 × 12 3⁄4 inches 338 pages with 6 gatefolds 300 duotone & color illustrations