The theme of this year's Met Gala, which happened earlier this week, was "Camp," inspired by a 1964 essay written by Susan Sontag, who outlined 58 definitions of the genre. "The experiences of Camp are based on the great discovery that the sensibility of high culture has no monopoly upon refinement," is listed as definition number 54. While camp can certainly apply to fashion and art, it can also apply to design, confusing the delineation between "good" taste and "bad," or perhaps doing away with them all together.

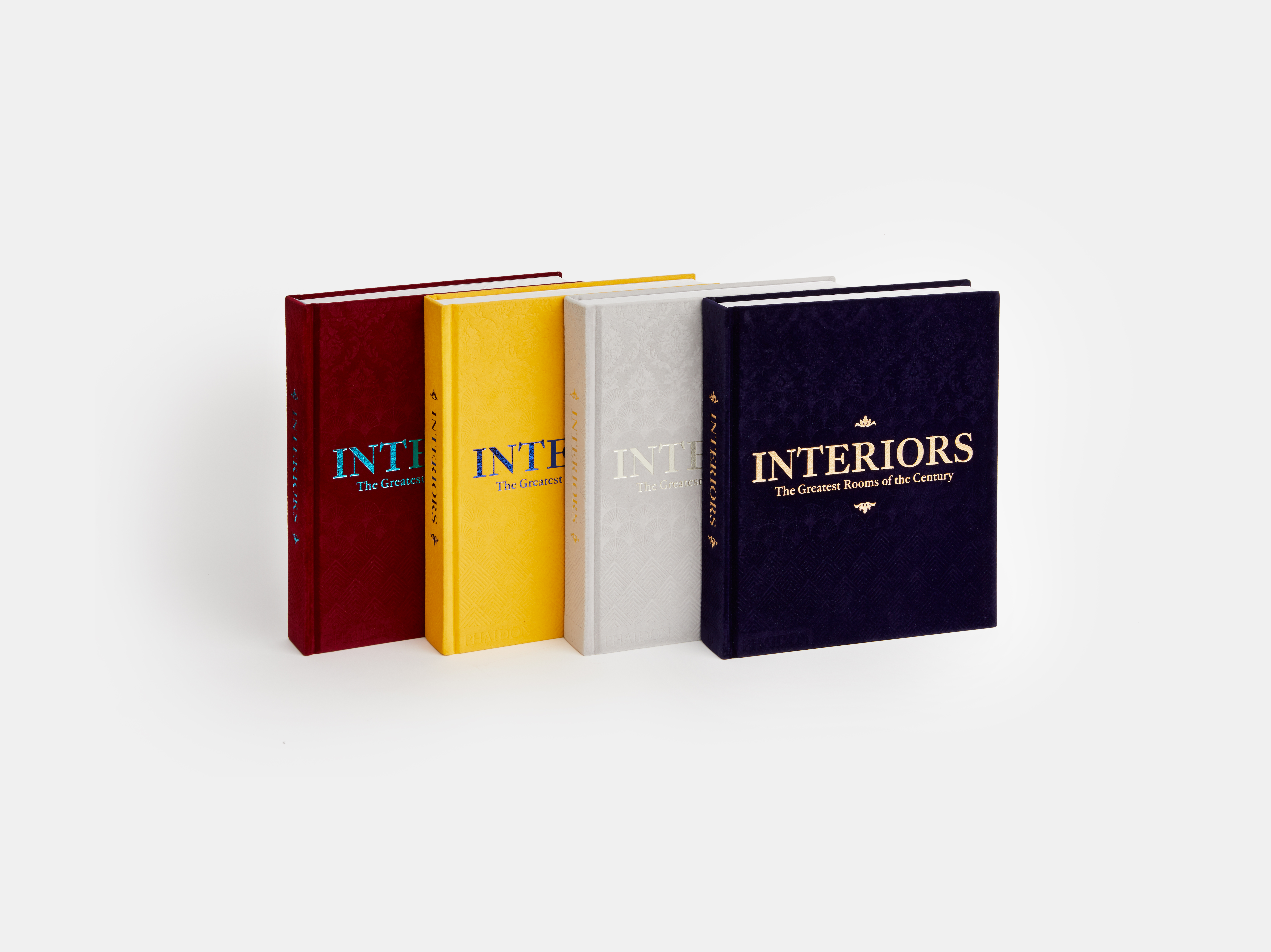

Here, we look at "The Good Taste Problem" in an excerpt from Carolina Irving's essay included in Phaidon’s recently published Interiors : The Greatest Rooms of the Century , which features 400 of the world's best living spaces created by over 300 of the most influential people in interior design.

For decades, Carolina Irving has been involved with the design world, whether as a writer, editor, or designer. She worked as an editor at Elle Decor, House and Garden , and Vogue Living before partnering with Penny Morrison to create Irving and Morrison, a decorative accessories company. She also has her own line of textiles, Carolina Irvington Textiles.

...

Worrying about good taste, the conundrum of what is good taste or bad taste, or no taste, has done more damage to interior decoration and one’s enjoyment of it than anything else. Trying too hard to get a room right, gather a consensus of positive opinion and approval, to follow the latest trends to the letter, impressing one’s friends or one’s spouse and, or, their parents or winning the acclaim of the “chic police,” by which I mean the arbiters you like best on Instagram and Pinterest, just isn’t what one’s home should be about.

Roger de Cabrol (designer and client), East Village Loft, Living Room, New York, NY, USA, completed 2014. Picture credit: David S. Allee

Roger de Cabrol (designer and client), East Village Loft, Living Room, New York, NY, USA, completed 2014. Picture credit: David S. Allee

I look at so much decoration now and a sort of nausea comes over me, seeing belongings and arrangements so socially codified with expected good taste yet so impersonal. This goes both ways, whether it’s the tyranny of hipper-than-thou trendsetters or the pronouncements of more established decorating arbiters. “Ghastly good taste,” the art historian and author John Richardson says with delicious mockery when discussing rooms bound up too tightly in decorators’ edicts. It’s an expression he credits to the British cartoonist Osbert Lancaster and one that he quoted in his memorable 1983 essay “The Sad Case of Mr. Taste” written for House & Garden , about William Odom, the decorator and Parsons School of Design professor who held great sway especially between World Wars I and II. Odom was the éminence grise behind McMillen, the leading decorator of the period, where Odom and Billy Baldwin rose to fame working for McMillen’s founder, Eleanor Brown, another legend of American decorating.

Charles Zana (designer and client), Zana Residence, living room, Paris, France, completed 2017. Picture credit: Courtesy of Jacques Pepion

Charles Zana (designer and client), Zana Residence, living room, Paris, France, completed 2017. Picture credit: Courtesy of Jacques Pepion

Odom created what Richardson described as the “high-style vernacular—a pared-down, up-to-date form of neoclassicism that is still, ninety years after it all began, in demand if not exactly in fashion. You know the look from back numbers of House & Garden : Directoire or Regency furniture (painted rather than gilded); mirrored walls hung with decorative paintings or architectural drawings; colorful needlepoint rugs set off by white carpeting; and Empire chimneypieces garnished with cachepots, obelisks, tole urns…”

This obsession with taste, ghastly good or otherwise, I expect dates back to the opinions of Elsie de Wolfe. In 1913 she published The House in Good Taste , and the title must have put the fear of god in everyone who suffered even the smallest pang of social insecurity—that their house could be considered either in good taste, or not. De Wolfe was fond of the expression “best standards;” another was “suitability,” which is a term that decorators have loved ever since. Unfortunately, it often suggests far too great a concept of correctness—whereas for me, suitability means something more forgiving, but nonetheless exacting.

“We are sure to judge a woman in whose house we find ourselves for the first time, by her surroundings. We judge her temperament, her habits, her inclinations, by the interior of her home. We may talk of the weather, but we are looking at the furniture,” so opined Elsie de Wolfe some seven years before women in the United States received the right to vote in 1920. No wonder suitability sounds so restrictive. Maybe because I’m getting older, I’m more of the school of “surround yourself with the objects that make you happy and make you dream.” Actually, age has nothing to do it with it. I’ve always felt this way.

Jozef Peeters (designer and client), Jozef Peeters Studio and Residence, DINING ROOM, Antwerp, Belgium, completed 1930s. Picture credit: © Photo: Museums & Heritage Antwerp, Bart Huysmans & Michel Wuyts; apartment: collection of the Letterenhuis, The Flemish Literary Archive & Museum, Antwerp, Belgium © Josef Peeters/Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2019

Jozef Peeters (designer and client), Jozef Peeters Studio and Residence, DINING ROOM, Antwerp, Belgium, completed 1930s. Picture credit: © Photo: Museums & Heritage Antwerp, Bart Huysmans & Michel Wuyts; apartment: collection of the Letterenhuis, The Flemish Literary Archive & Museum, Antwerp, Belgium © Josef Peeters/Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2019

One of my favorite writers, Lesley Blanch, said it best. She traveled the world and her rooms were filled with the most personal and evocative mementos of her explorations, with things like a Caucasian rug hanging on the wall and a favorite old swatch of toile de Jouy in a frame, more rugs and more fabrics on sofas and chairs. Her way of decorating wasn’t really even decorating, per se; it was collecting and displaying—an haute bohemian style as photographer Miguel Flores-Vianna would say. I can remember seeing Blanch’s house in Menton, France, photographed for House & Garden by Henry Clarke in 1974. It was a revelation to me.

Blanch had many needlepointed pillows that she’d made for herself. “My cushions are so many magic carpets transporting me back to faraway places I have known and loved and now re-create in terms of gros point,” she said. “As I stitch, they come to life again, and I am once more in the dappled shadow of Aleppo’s souks, in the Pachmakli along the road in Turkestan, or on a rooftop in Delhi…”

She despised anything en suite , meaning rooms so tastefully decorated and controlled that they could practically be gift wrapped with a bow. “My rooms are acts of defiance against every rule of the pundit decorators,” Lesley Blanch said. “Now east, now west, my rooms reflect the globe. Cultures, races, climates, colors, and epochs mix in harmony here, as do bargain and chintz… I find my things very good company: they are not capricious, or boring or demanding. They do not have to be entertained, or dined or wined, like so much of the human species. Surround oneself with the things you love and your house will make you happy. I never decorate; I just make sure that I’m going to be comfortable and let the effect come with the living. You must have comfort first. Everything else follows naturally.”

Julia Morgan, Hearst Castle, for William Randolph Hearst, Doge’s Suite, San Simeon, CA, USA, completed 1947. Picture credit: Shutterstock/gnohz

Julia Morgan, Hearst Castle, for William Randolph Hearst, Doge’s Suite, San Simeon, CA, USA, completed 1947. Picture credit: Shutterstock/gnohz

This isn’t exactly what the majority of the “pundit decorators” have been telling people over the past century. So much of their message has been social advice cloaked in decorating directives, how to fit into a community by way of fabric choices and a can of house paint. My taste? I am a dreamer and a romantic; it’s the romance of things and the thrill of adventure and discovery. I feel like I am an animal with a cocoon on top. Everywhere I go I bring the same things because I need to be surrounded by that atmosphere. But what works for me may not work for someone else.

You have to find out what these things are for yourself. There are guideposts, of course; proportion, clarity, and balance are considerations when negotiating in a finite-sized space, or in any space for that matter, but I really don’t think there is such a thing as absolute bad taste. If the person’s room is authentically theirs, and this is how they are happy, then it is their taste. It suits them.

...

You have to learn to look for yourself. You can have genes that drive you towards beautiful things, but if you don’t, then you can also learn. Only ten years ago, if you had told me about Rudolph Steiner furniture I would have told you I hated it—contempt prior to investigation. Too earnest, too natural, too simple, too crunchy and wholesome, but then I kept seeing it, and the more I saw it, the more I learned, the more knowledge I gathered, the more I have come to appreciate it, love it almost. Steiner was one of the great reformers of the twentieth century, and his vision of anthroposophy, the principles of art, science, and spirituality unified as one, resonates so deeply in his designs. Instead of contempt, I now find his work endlessly fascinating.

Phaidon's

Interiors: The Greatest Rooms of the Century

is available on Artspace for $79

Phaidon's

Interiors: The Greatest Rooms of the Century

is available on Artspace for $79

One also goes through periods when one likes different things; what appealed to you a decade ago becomes indigestible now. Besides, there isn’t an absolute concerning good taste; how could there be? Isn’t it all a matter of opinion? Visit one of the most acclaimed apartments of one the great Park Avenue ladies and you find it impeccable, and so harmonious, nothing out of place. “Great decorating” Elsie de Wolfe might call it, while some-one like Christopher Gibbs might have found it the height of bourgeois naffness—everything too en suite , too matchy. I find it absolutely divine but I wouldn’t want to live in it.

Tony Duquette & Hutton Wilkinson, Palazzo Brandolini, for Mr. & Mrs. John N. Rosekrans Jr., salon, Venice, Italy, completed 1980s. Picture credit: Fernando Bengoechea

Tony Duquette & Hutton Wilkinson, Palazzo Brandolini, for Mr. & Mrs. John N. Rosekrans Jr., salon, Venice, Italy, completed 1980s. Picture credit: Fernando Bengoechea

Contemporary architects would say there isn’t bad taste, there’s only taste. This is the postmodernist opinion, no absolute truths about anything, including the truth. Diana Vreeland’s famous quote is, “A little bad taste is like a splash of paprika. We all need a splash of bad taste—it’s hearty, it’s healthy, it’s physical. I think we could use more of it. No taste is what I’m against.” But even no taste is its own kind of taste—a “good taste of bad taste” as Susan Sontag wrote in her essay “Camp.” There’s always taste and, yes, there is bad taste; there is vulgarity. Fast-food restaurants, in my opinion, are the height of visual vulgarity. They come out of nowhere, they aren’t camp, and they aren’t ironic; they are like carbuncles, huge blemishes, on the face of the earth. Only through resignation to their persistence do we see their place. Why can’t some great architect, like Tadao Ando, design them, and make them remarkable to look at?

The closest I can come to defining good taste, besides saying that you know it when you see it, is focusing on this idea of suitability that runs through the literature about interior decorating, as mentioned earlier, dating back to Elsie de Wolfe and beyond.

Ashley Hicks (designer and client), Hicks Set in The Albany, living room, London, England, UK, completed 2015. Picture credit: courtesy of Ashley Hicks Studio

Ashley Hicks (designer and client), Hicks Set in The Albany, living room, London, England, UK, completed 2015. Picture credit: courtesy of Ashley Hicks Studio

To me, suitability means much more than correctness. It signifies genius loci : the enveloping, protective spirit of a place. When you are attuned to this spirit, when you learn to look for it, there is a purpose to the design of your room. It tells you where the furniture is to be put, the reason for creating a conversation corner with a lamp where you can sit, and where a chair should go, an ottoman, a table, the bed. Otherwise, without this spirit, you walk into a house and it’s discombobulating.

“Consult the genius in the place in all; That tells the waters or to rise, or fall,” Alexander Pope wrote. He was talking specifically about landscape design, but if that’s what the decorating pundits also mean by good taste, then that’s what I believe in too.

RELATED ARTICLES: