"Research is formalized curiosity; it is poking and prying with a purpose." This quote, printed on one of the many perusable index cards within Kameelah Janan Rasheed 's installation in the New Museum's 5th floor Resource Room , does a pretty good job of summing up the intent of the exhibition. The artist—a professor, curriculum writer, and former high school teacher—thinks about her creative processes as "primitive hypertext," a term coined by science-fiction writer Octavia Butler to describe how "the sensory and cognitive wanderings of a relaxed and attentive mind... produce nonlinear associations from which new understanding arise."

The index cards sit on a table next to a photocopy machine—an invitation to leaf through the material on view and make copies to bring home. On one wall, shelves are stocked with the artist's collection of books and pamphlets about the diverse histories of black social movements, schools, and learning strategies in the US. A few examples: a xeroxed, spiral-bound pamphlet called "Black Papers on Black Eduction," a school-published collection of poetry written by young students, and an essay on the "blackness of blacknuss" by artist Arthur Jafa (who currently has a solo show at Gavin Brown).

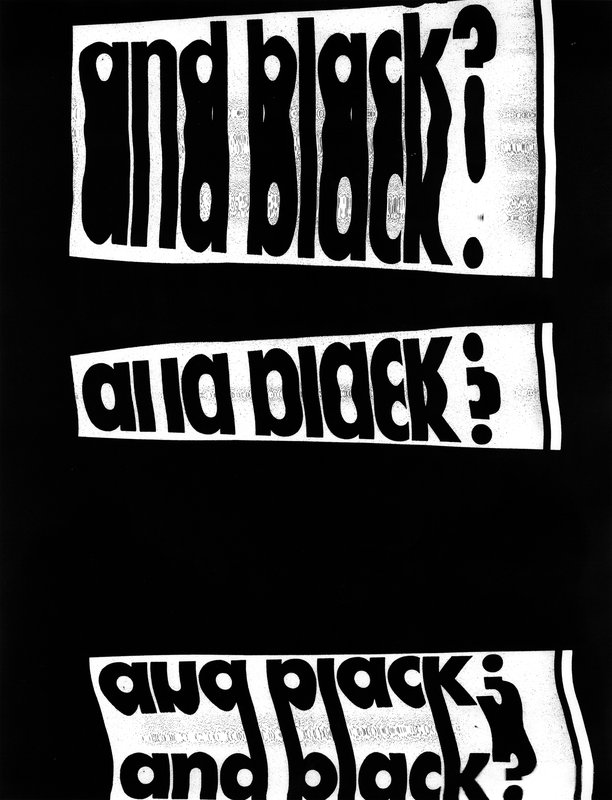

Kameelah Janan Rasheed's installation at the New Museum. Photo: Artspace.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed's installation at the New Museum. Photo: Artspace.

Rasheed's library sits adjacent to an installation by The Black School (Joseph Cuillier and Shani Peters). Together, they allow for self-directed research into both the history and future of black education in the US, and posit education "as a right and means to social justice—both of which have been challenged by legacies of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and present-day systemic racism," according the New Museum. As Rasheed says in the conversation below, "If you live in a country that previously enslaved you, there's no reason to trust that the educational system will not encourage the types of thinking that undermine your humanity." Cuillier and Peters' The Black School is working to counteract this; founded in 2016, it's "an experimental art school based in New York that uses a socially engaged, proactive practice and black history to educate black/POC students and allies in becoming radical agents of social and political change." In their installation at the New Museum, they present a prototype for a classroom design that involves malleable soft pillows that can be rearranged to serve multiple functions, and cascading fabric from the ceiling that can be used as tent-like enclosures.

The Black School's installation at the New Museum. Photo: Artspace.

The Black School's installation at the New Museum. Photo: Artspace.

In the conversation below (originally published as a pamphlet by the New Museum and edited here for brevity), New Museum's associate director of education Emily Mello interviews Rasheed, Cuillier, and Peters about their work, their inspiration, and their thoughts on black education. Supplemented by a range of interactive public programs, " The Black School X Kameelah Janan Rasheed " is on view at the New Museum in New York until September 16th.

...

What is the relationship between your work and histories of black radical movements and the ways they are marginalized within or erased from institutional memory? Do you engage differently with this content in your artistic practice versus in your teaching?

Shani Peters: The approach that we take in the Black School workshops is action-based. My teaching work is the public engagement space of my practice. We are trying to go in and get the young people thatt we're working with to act as those figures in black history that we too often just think of as faces and bios on a wall during Black History Month. We go in with a structure designed to get students thinking about the ways that they can impact their communities, in ways that people may have done before them. We do this without saying, "This workshop is going to be about Fannie Lou Hamer, and this is what Fannie Lou Hamer did, and now we're going to do something like that." We start from the perspective that Fannie Lou Hamer was thinking critically about what was needed in her community, and then go from there.

We might assume a consensus for the necessity of creating spaces that center the creativity, history, teaching, and learning of students of color. However, we live in an era that threatens to erase the histories of such spaces and to challenge their future possibilities. Recently, the Secretary of Education said that historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were "pioneers in school choice," a statement that failed to acknowledge the true history of their founding and instead serviced an agenda of privatizing education. At the same time, there are sentiments that such spaces are separatist efforts that might preclude or undermine efforts toward integration. These responses come from both the right and left, but most often from a white perspective. Can you speak to generative examples in US history of self- and community-led learning and knowledge production that remain relevant to you and your work today?

Joseph Cuillier: We have to acknowledge we're not all together. That's why these institutions, these community learning spaces, need to be created, because there was never integration. We're less integrated than we ever were. That's the reality. So much of American history, past and present, is about obfuscating those facts, pretending that we're all together, when every institution in society is working so that we're not. Going back to the Civil Rights Movement and Brown v. Board of Education, a lot of those fears about integration and having black students in schools with white students was the catalyst for this backlash. It's still happening with the current administration, which is using black students as well as immigrant and Latinx folks as pawns to consolidate the power of these disparate white populations who don't necessarily have the same interests or the same class background, but can consolidate around fear of black and white students mixing in educational spaces, or relationships, and so on. A lot of that fear is used to build white supremacist political movements. I went to an HBCU, so I know those spaces have nothing to do with whiteness. Though those institutions were built because black people weren't allowed to participate in a white world, being in such spaces isn't about a reaction against white supremacy. It's really about black people coming together, learning from each other, building with each other.

SP: I think about that irony: that conservative and fascist governments always speak in opposites. School choice is actually the exact opposite of choice. Black people in the United States of America have never simply had choices: it's always in part that we are here making the best of the circumstances. I want to be clear that that's still what's happening. We're all working in this way because this is the space that we've been able to carve out in which to actually facilitate self-determined education programming. We're not saying that things were better during Jim Crow segregation. People didn't have anywhere near the resources that white schools had, but because there was no choice, the entire black community was in that situation: both those who had some access to resources and education, and those who didn't. And you still hear of fond memories and great experiences that come out of that entirely forced condition. The kind of work that we're doing here, it is elective. It's a matter of us reaching out. It's interesting to hear Joseph talk about actually studying in an HBCUs in the US were necessitated by white supremacy. We find ways to get what we need out to these situations.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I've thought about generative organizing from the personal or hyper-local to the local to the regional, and so on. I've thought about mothering as a pedagogy and as my first and most intimate encounter with organizing, in the way that my mother advocated for my four brothers' and my access to radical and rigorous learning opportunities. Her level of involvement in schools was my primary example of organizing, ensuring that certain types of knowledge and learning were prioritized. I remember my mom constantly being present at our schools, in the back of a classroom, literally taking notes, and then approaching teachers after class to ask them why they taught certain topics in a particular way and to suggest curriculum changes. She did not trust that our school was going to ensure that we had the type of education that we needed. Seeing that gave me a very clear example of how action didn't require being part of any particular social organization; it meant being a black mom who was aware of the stakes.

At the local level of my city, East Palo Alto, I would actually use self-knowledge to move forward and develop productive skills that were useful for the community, learning about things that were happening every day to sustain culture over time, like the Nairobi school. There's an organization in East Palo Alto called Youth United for Community Action, which is a group of young folks of color who basically shut down a toxic waste disposal plant in our neighborhood through organizing around education, doing toxics tours and teach-ins. I'm also interested in the long history of black people organizing schools and educational institutions as a form of self-determination and community building for the purposes of establishing a clear position in this nation. Much of this is borne of, again, an awareness of the stakes—if you live in a country that previously enslaved you, there's no reason to trust that the educational system will not encourage the type of thinking that undermine your humanity. There's not going to be a form of teaching that's actually going to mobilize people against the structures that are oppressive to them.

[related-works-module]

You all use vastly different visual language and media, but you seem to share an interest in shifting between legibility and opacity. Art welcomes this dance between the clear and the ambiguous. Even if we assume that all art contains some form of ideology, we rarely hear the word "didactic" bestowed as praise in the realm of art-making. On the other hand, such clarity is often prized in education. Do ideas of legibility and opacity relate to your thoughts on teaching? And do you find a poetics in your approach to critical pedagogy?

JC: Some of the things that are privileged in fine art are privileged in order to uphold the inequalities that we are fighting against. When you're approaching art-making and you have multiple qualifiers for yourself as artist, educator, and activist, you have to balance those things out. Sometimes—depending on your audience and your content—you may need to be more legible than other times. Whereas if your qualifier is just "artist," your work could be more about personal exploration when it is about creating some kind of social exchange between your audience and what you're doing.

KJR: With regards to teaching and my artistic practice, I think about strategic opacity as a form of invitation. I think about these moments in which something is not absolutely clear as an invitation for discovery and investigation. Or I may teach a particular global history lesson in a way where I already know what the document's going to say, but I intentionally build out these activities for students to have to go through an investigation, an inquiry. I think that the choice to go through discovery, serendipity, and chance is an important part of the learning process. It's also an important part of art viewing. I think so much of looking at art has become about getting in and out quick. I very much resist any abbreviation of my existence and any abbreviation of my work. I intentionally make work that asks people to engage in some form of cognitive labor. I respect and value the cognition of people looking at the work. In both cases—that of my art practice and my teaching practice—I am really interested in what it looks like for us to make durational choices, to say "I'm going to roll with this," even though it might be confusing, even though it might be difficult, because that discomfort can be generative. Given the vast commercialization of black histories, black identities, and black cultures, I attempt to work in the opposite direction, to say that I am choosing not to make it easy. To understand and unfold blackness requires work.

Someone once told me that my work was subtle and quiet. I like quiet. I like subtle. I really do think there's a space for black people to make quiet work; there has to be. I think that essence of being quiet is something that black people are not afforded. I was so relieved when I read some of Kevin Quashie's work late last year. It was an affirmation of a lot of feelings. He challenges the notion that the only way that black people can make work and express themselves is through something that's loud and expressive, which forecloses any opportunity for us to be multifaceted human beings with a range of emotions and a range of agility.

How has the Black School approached reimagining a classroom space?

SP: Classroom spaces are historically not ideal in terms of physical construction, but for us, overwhelmingly, they are not ideal in that they're structured from an institutional point of view cultivated out of white supremacist patriarchal capitalism, and therefore aren't to be trusted to cultivate the best in human beings, to cultivate true thinking. They are there to produce worker models. We want to shift the perspective, fundamentally, to a place of wanting to see people be their best versus wanting to see people fit into societal programs.

JC: I'd like to go back to bell hooks's idea that educational spaces are designed to be patriarchal and hierarchical. I'm trying to physically reimagine those spaces by having adaptable architecture: draped art fabric can become an enclosure; soft furniture can be linear or circular. I'm also thinking about how intimacy can be radical. In intentionally black spaces, intimacy is important to the radical pedagogy that we're inspired by and going for: creating spaces that use black style to create something that is intimate, and by being intimate, tapping into power.

We are thinking about what educational spaces are actually inspiring alongside what educational spaces currently exist, the ones we're forced to be in. We're thinking about living rooms, as opposed to classrooms. And about spiritual places: sanctuaries and altars, rather than prison-like bars on the window and uninspiring colors on the wall. Rather than taking this factory-like model, our project takes up a radical approach to building an educational space.

KJR: I do hope that, as a result of this project, there can be greater understanding between folks who are working full-time in public schools and people who are coming in as part-time teaching artists or for after-school programming. I've been a teaching artist. I've done after-school programming. I've worked in traditional settings. Now I develop curriculum. I think that one of the things that is often forgotten is that even though we're working within a very particular set of constraints as K-12 teachers who have mandates with standards, there are a lot of really amazing, radical things that are happening between and through those interpersonal relationships that you are building with students. Innovation is often driven by constraints. I've watched teachers who are experts in their pedagogical technique, honed over years of navigating public school institutions, design amazing and durable learning experiences. These people are on the front lines, negotiating competing interests and discovering how to make sense of a massive institution. I'm hoping that through this residency we will have opportunities to connect with public school teachers, to bring together classroom teachers and artists who are not together during the day to actually establish a cooperative relationship, rather than an antagonistic one. It's important to have that space, and to have black women and black men who are physics and history teachers there in traditional schools. This strategy would involve people working in both spaces until we actually arrive at a place where schools are functioning the way that we need them to. I think there's opportunity for a symbiotic relationship between teachers and artists, and I hope it's nurtured and discussed and throughly worked through during our summer here.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BHQFU on How to Run a Free Art School with the "Worst" Business Model

Don't Want to Pay for Art School? Here's a Streamlined Syllabus for Getting Your Own DIY MFA at Home