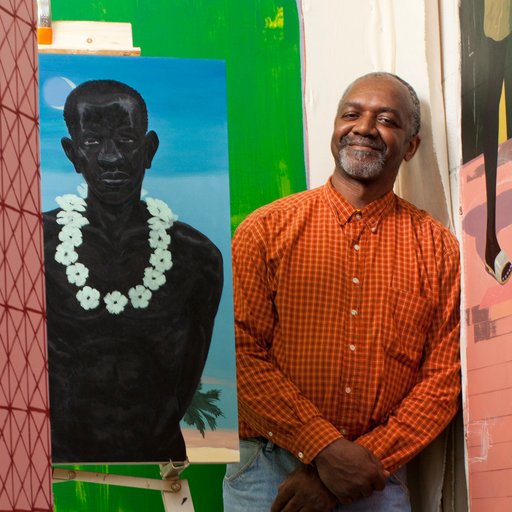

Phaidon's Contemporary Artist Series boasts a range of monographs from some of the most important artists of our time, from Ai Weiwei and Jenny Holzer to Frank Stella and Yayoi Kusama . Most recently, Phaidon worked closely with Kerry James Marshall to produce a monograph —providing a unique opportunity for Michele Robecchi, Phaidon's commissioning editor for contemporary art. Spending long days in Marshall's studio, sifting through the artist's archive and picking his brain about his work, Robecchi gives us insight into what it's like to translate painting to the printed page, about working with Marshall on such an intimate scale, and about the art and science of making a monograph.

How did the Kerry James Marshall monograph come about?

A few years ago I went to see his retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp. It was the first time I got to see a comprehensive survey of his work and, without lapsing into metaphysical parlance, that’s where the seed was planted. I was already familiar with his work, I remember seeing it in Documenta, but I never met him before and it was only when he had his solo show at David Zwirner in London in 2015 that I had the opportunity to discuss the idea of a book with him. At that time I didn’t know he was going to have a major traveling retrospective in the States. Fortunately he was interested, even with an engagement of that caliber on his plate.

What is it about him that made you want to do it?

I just think he is one of the most interesting artists around. His work is so relevant both politically and aesthetically. In a way he carved the path for a lot of artists that came after him. Kerry always had great ambitions for his work, he is one of those artists who made a deliberate decision to stick to his own ideas even in less-favorable times with the knowledge that sooner or later he would have been proved right. It has taken a while for him to get where he is today and finally get his dues. I guess he was ahead of his time for a lot of people. The art world can be really slow at catching up with things.

He suddenly has become really hot right now, so the book is well timed, isn’t it?

It sure is. But it’s very dangerous to make a book because of the hype. I would have never entertained the thought if I didn’t believe in what he does. The retrospective at the Met in New York, the MCA in Chicago and LA MoCA generated a lot of attention but even discounting that kind of institutional recognition, the intrinsic quality of his work is outstanding and that’s what ultimately counts.

Kerry James Marshall

Kerry James Marshall

What is his work about?

Marshall believes in the Davincian idea of art as science and how art can serve to help us progress towards certain goals we have as humanity. His work is about creating a platform for ideas—it is not a place for self-expression, although laterally there is a lot of it. If you look at his paintings, you can see that nothing is casual. Visiting his studio was a humbling experience—it’s really a laboratory for ideas. It’s not just about composition and technique. In his essay in the book, Greg Tate talks about how, as a young boy, he went fishing and boating on America’s great lakes with his family as a kid, and how Marshall alone depicted the normalcy of these recreational pastimes. The black community has been massively under-represented in American museums so far and a great part of Marshall’s work is set to rectify this historical mistake.

How closely did you work with him?

Very. He was great to work with in that respect. One of the founding principles of the Contemporary Artist Series is that we work very closely with the artist. So much has been happening to him over the last few years. The US retrospective, all those talks and conferences, the Time Magazine thing [Marshall was just recently nominated as one of the most influential people in the world by the magazine]—it’s been a hell of a ride for him over the past two-to-three years but he always found the time to focus on the book and was appreciative of the hard work we put into it. I think he knows that a book, unlike an exhibition, is here to stay. It has to stand the test of time, and he really made sure that we would end up with something special.

What did you learn about how Kerry James Marshall works as an artist by working with him?

I learned a lot. It’s kind of inevitable when you embark on an immersive venture of this magnitude and time scale, but when the artist is very involved, as Kerry was, you wish the project would never stop because there is just so much to learn. I was already familiar with his work but having opportunity to listen to how some ideas came about or how the work is made in a certain way and why was a great privilege. It’s great when artists have that attitude. And it helps make the book better, because once you know all these things, you feel even more compelled to do the work justice.

What’s the hardest bit to get right with a book like this?

The most important thing was to make a book that would reflect the spirit of the Contemporary Artist Series but that at the same time would offer something more, or different, from the other publications he has to his name. When I went to see him in Chicago he showed me one of those museum guides, where works are reproduced in thumbnail size. He opened it on a spread and said: ‘Do they have to be bigger than this? Isn’t that enough information’? I could totally see where he was going. We basically agreed on making a book that would present the work as an oeuvre and that would illustrate process as well as practice. He was really open in that regard and he gave me a lot of unpublished material. Kerry works alone, there are no assistants around him, which is unusual for an artist that busy. He has a peculiar filing system: drawings, photographs and ephemera are scattered around the studio but he knows where everything is. I walked away with so many incredible things very few people have seen before, like the poster of the very first exhibition he was in or the original sketch for his seminal painting

Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self.

He trusted me with a lot of his archive and I was immensely grateful for that.

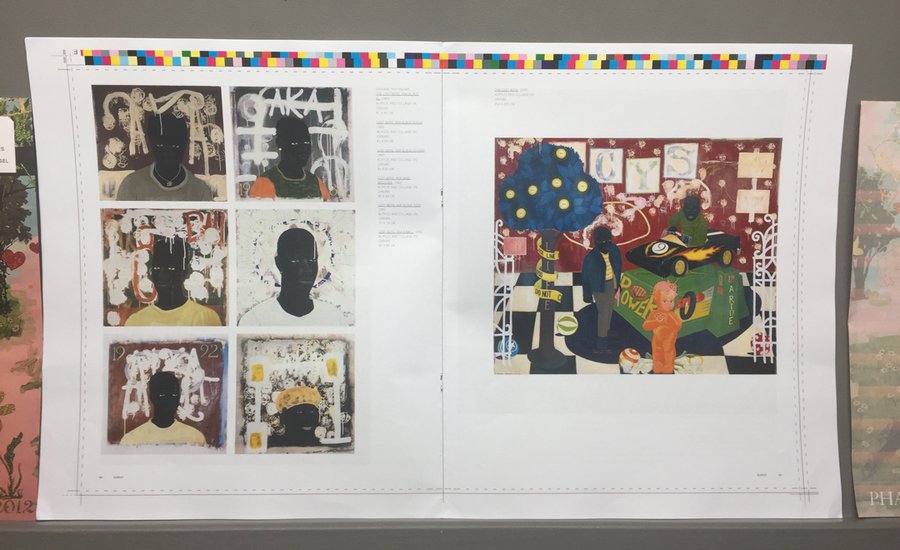

Kerry James Marshall

Contemporary Artist Series monograph in production in the Phaidon Light Room

Kerry James Marshall

Contemporary Artist Series monograph in production in the Phaidon Light Room

Kerry James Marshall’s paintings tend to be very large in scale. Are some paintings more easily translatable onto the book page than others? What other challenges or considerations come up when reproducing textured, large objects as flat, scaled images?

I normally let the degree of information present in an image be the guiding factor rather than the size, unless the latter resonates with the exhibiting space in a way that you simply cannot ignore. For example, in 2012 Marshall painted a wonderful tryptic of semi-monochromes called Red (If They Come in the Morning) , Black and Green . Because of their size (roughly 2 x 5 meters), in all his previous books they have been featured each on a double page spread. In our book they are all on the same page—a solution that enables the reader to see the relationship between them (they form the Pan-African flag) and still appreciate the details. Conversely Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self is reproduced almost in the same size, if not slightly larger, than the original painting because you need to see it from a closer distance.

A big challenge for me was Heirlooms and Accessories (2002). It is one of the most powerful works Kerry has made—a sequence of lockets that at closer glance turn out to be close-ups of three white women present at the lynching of Thomas Zipp and Abram Smith in Indiana in 1930. When I went to see the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York I noticed that the background of the painting gets often washed out but it is actually crucial as it contextualized where these portraits come from. I think each image is a challenge onto itself. The most important thing is that they are represented truthfully and consistently all through the book.

Kerry James Marshall

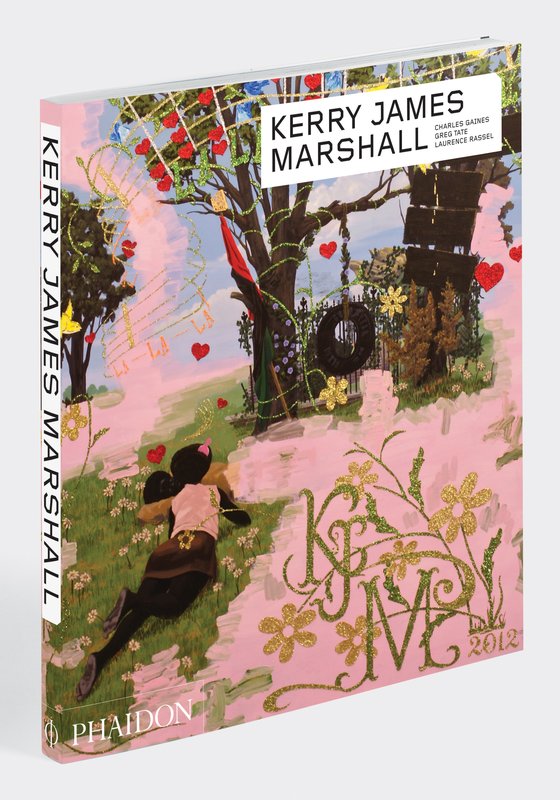

(2017) is available on artspace for $49

Kerry James Marshall

(2017) is available on artspace for $49

What was the thing that was perhaps most interesting for you?

There are so many. It was interesting to hear about his time at the Otis College of Art and Design, how he came to paint what he does, and his view on art and society in general. We have a great conversation between Kerry and Charles Gaines in the book and I must have listened to the audio file at least ten times. Just plenty of delicious and nutritious food for your brain.

And the bit that you’re most pleased with?

The fact that he likes the book. He saw it for the first time in Berlin a few weeks ago and he seemed genuinely happy with the way it came out. My number one priority, when it comes to work on a monograph, is to always please the artist. The best reward you can get as an editor is when you see that happening.

What do you think the reader will get from it?

I hope the reader will get from it as much as I did. Charles Gaines, Laurence Rassel and Greg Tate all provided great contributions. The selection of images we put together is quite exhaustive. It touches on practically every cycle Marshall has produced over the years, and it features also some of his lesser-known but equally important conceptual art work. There is also a selection of his own writings, including an essay on his relationship with Andy Warhol and Pop art, although a personal favorite is probably his ‘Letter to a Young Artist’. It’s such an inspirational and powerful text. He wrote it in 2006, and ten years on, it’s still burning.

What is a monograph, anyway?

In our case it’s a collaborative effort with artists resulting in a comprehensive presentation of their practice. Our goal is to celebrate the work by providing an exhaustive insight into what they do without the ambition of creating a catalogue raisonné. I have a background in curating and I see these books as exhibitions on paper. We are obviously exempted from a lot of practicalities like shipping, insurance and other technical aspects but intellectually it is very much the same process. It’s about establishing a relationship of mutual trust and developing a narrative within the presentation of the work. Another difference is that books, unlike exhibitions, are around for much longer, and as such there is an enormous pressure to get them right.

Can you talk a little bit about the different sections of the book and how they add to our understanding of the work?

Each book has six chapters. There is a conversation between the artist and a person of their choice, a long essay providing a comprehensive overview of the work, a shorter text examining one single work, a selection of artist’s writings, a biography/bibliography, and the publication of an existing piece of writing that the artist identifies as having particular significance for the work. Occasionally we replace this last chapter with a studio visit, where we send a photographer to document the environment in which the artist operates. This structure, with very little variations over the years, was devised by Iwona Blazwick, the founding editor of the series, and it’s still working really well. I think having multiple authors, each providing a different reading of the work, coupled with the artist’s involvement, is what ultimately makes this formula so successful.

How do you chose the contributing writers?

The choice of authors is very much the result of a dialogue between the artist and me. In general I tend to encourage the artists I work with to see the book as an opportunity to establish a relationship with people they like but were never able to work together with for some reason. It is of course of paramount importance to have at least one author very familiar with the subject. The chemistry between artist and writer in the interview is particularly relevant. In the same breath, it’s nice to leave room for something a little more experimental—those little adventures on the left, where you involve people coming from different creative fields who have an affinity with the subject or writers who bring a fresh perspective on the work.

[related-works-module]