In the Whitney Museum’s first biennial of its new Chelsea home, one of the most controversial works is one of new media: Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017) is experienced through virtual reality headsets. Via Oculus Rift, the viewer is forced out of the museum and onto a New York street, where the artist waits with a baseball bat. Before viewers have time to accustom themselves, Wolfson swings, repeatedly wailing the bat and stomping his foot into the face of an animatronic doll—rendered lifelike through post-processing—which spouts too-human blood. Back in the museum, metal handrails help deter viewers from looking away. All of this is overlaid, through headphones, with the recitation of a Hebrew prayer.

There’s been no shortage of cynicism among critics for Real Violence, though Wolfson’s no stranger to scathing reviews—among them, Artspace’s harsh analysis of his May 2016 show at David Zwirner, written by artist Ajay Kurian, who is also present in this year’s biennial. Real Violence has been quickly dismissed for being superficial, after nothing but shock, a meritless, simulated reenactment of the kind of senseless violence experienced all too frequently by people who, unlike Wolfson and his doll, aren’t straight, male, and white.

A more forgiving reading of Real Violence, however, might take the medium into greater account, and the ways in which virtual reality in particular is capable of replicating the visceral elements that constitute “meatspace,” typically left behind by cyberspace. Such a premise might lead to the conclusion that, in a sense, Real Violence is a form of a technological sabotage directed toward a certain kind of media consumer—say, a cynical museum patron, a savvy connoisseur of images for whom real violence is a thing only experienced on TV.

Wolfson aside, the inclusion of Real Violence in the Whitney Biennial marks a milestone for the medium of virtual reality—which, despite its recent acceptance, has really been around in some form or another for decades. Over the past several years, several tech companies have competed to bring VR to the mainstream, and even artists are caught up in the hype. The Moving Image Art Fair, for example, has included VR works for a number of years since its inception in 2011, but co-founders Murat Orozobekov and Ed Winkleman told Artspace that 2017 was the year they really honed in on the medium. This year, VR works made up over a third of the show.

The proliferation of artist-made VR “experiences” (as the industry likes to call them, in distinction from flat-plane “videos”) has parallels to other wavelike interests in digital media. Net art of the early aughts is an easy comparison because of both its exploration of emerging technology and the content that appeared seemingly overnight. In fact, the history of images in general is inextricably tied to technological developments, as artists have always been drawn to tools that might unlock new modes of vision. This historical through-line extends back far beyond virtual reality and the web. Much as Post-Internet art has exemplified the acceptance of the internet as just another facet of life—rather than a technological marvel worthy of exaltation in its own right—so too has photography become just another tool available for use, and so on, all the way back to shadow-puppets thrown by firelight. The Moving Image Art Fair was held in Chelsea’s Waterfront Tunnel, a fitting venue to showcase images of transporting effect: A tunnel, after all, is little more than a manmade cave.

Though we’re in the middle of a VR phase now, eventually the novelty of it too will fade. Only then will we know to what extent projects like Real Violence, which hinge on some function that only a certain technology offers, can speak beyond their code to the social and political circumstances of a point in time. Until then, though, there’s much to sort out.

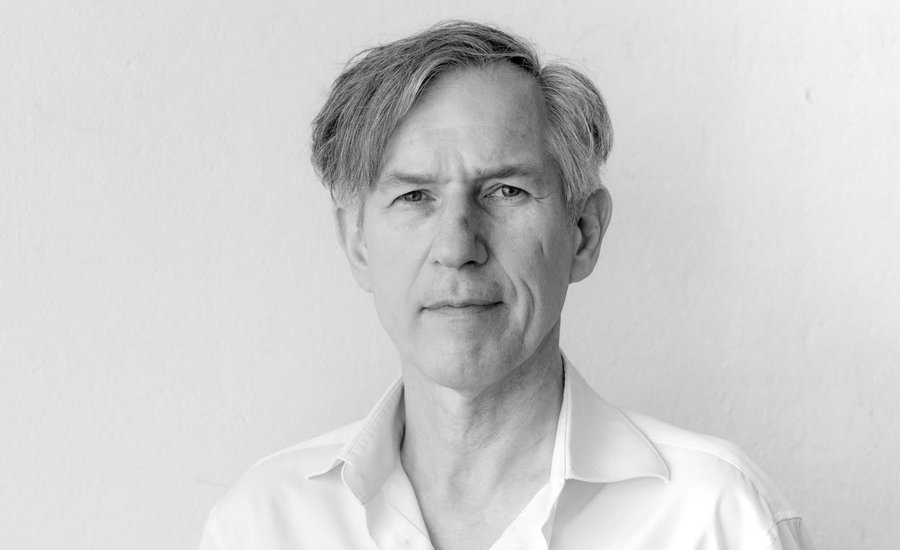

For help making sense of the role virtual reality and other new technologies play in artistic production, we turn to Wolf Lieser, the founder and director of the Digital Art Museum (DAM). After Lieser founded the DAM in 1998, it existed for its first five years as an online-only hub contextualizing then-emerging net artists within the legacy of digital art. Then, in 2003, DAM opened a gallery in Berlin dedicated to representing artists who work in digital media. Artspace’s Will Fenstermaker first met Lieser at the Moving Image Art Fair, where DAM Gallery showed a 2001 work by Casey Reas—a slow, deliberate construction of a complex pattern, modeled by a programming language developed by the artist. A few weeks later, they met again via video chat to continue their conversation on the past and future of digital art, the institutionalization of virtual reality, and the challenges of avoiding technological spectacle.

Can you begin by telling me about the birth of digital art?

Well, if you look at the beginning, there was a philosopher in Stuttgart, Max Bense, who was really influential for some of the artists who started to work digitally in the '60s. He came up with the idea that you can totally rationalize a concept of art. Sol LeWitt and people like that in the '60s also had a similar approach. They wrote a concept and then it was executed by someone else. So, if you write a program, there’s basically nothing different. You put in all the aesthetic rules and the parameters, and then it’s executed by a computer rather than a person. Conceptually, that’s very close. They share this idea that you can program art, which was very revolutionary at the time.

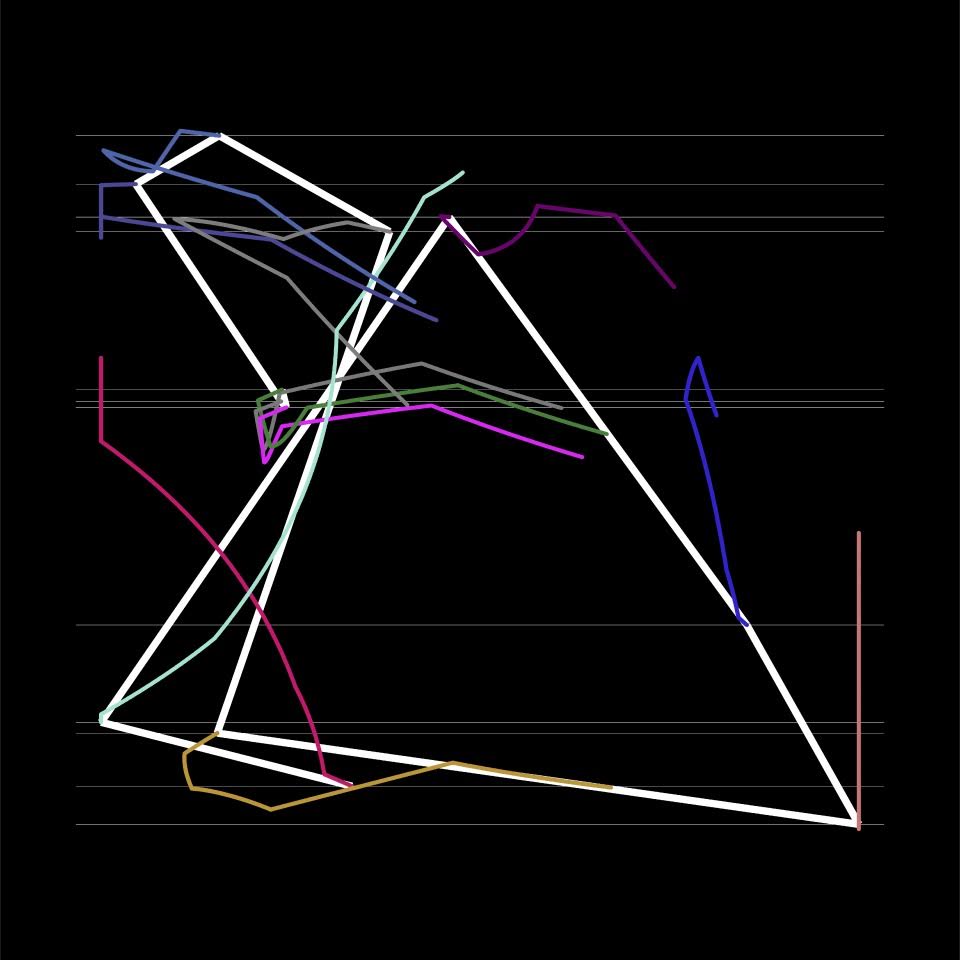

Of course this went very far away from this romantic idea of the 19th century artist, or the idea that you had to have some kind of emotional surprise, or some kind of vision that suddenly happens and brings about great art. Early digital art was really based on the idea that you can discover different possibilities on the computer, and then amplify them with different kinds of algorithms. So, you basically build a kind of tree of algorithms, starting with something small, which becomes bigger, or goes in different directions. All of the artists working in this field will tell you that when they use an algorithm, they are always surprised when they see the final results. If you see a software piece by Manfred Mohr, it’s incredible to think that at the beginning he’s only working with cubes, nothing else.

But it just evolves into this whole other thing.

Yeah, they get into these complex structures, and Mohr makes little things visible. Even though this is a very rational concept, you’ll still be surprised by the aesthetic impressions that it can bring about.

Manfred Mohr, P2200.6 (2014–15)

Manfred Mohr, P2200.6 (2014–15)

The late Harold Cohen—a pioneering artist who coded a machine called AARON to paint—talks about “the decision-making power of programs”; once you set them free, they go on to make all sorts of decisions that take the work away from where you began.

Yeah, Harold is a special example because he was trying to develop a kind of program that paints, more or less. The machine he developed produced some kind of picture, and developed them further through different variations, but they still look very painterly. His aesthetic ideas and his aesthetic perception—how a picture or a painting should look—show very well in the final result, and from my perspective, that was a limitation.

At the beginning, digital art was a really new, conceptual approach to how to produce and think about art. If you look at it now, fifty years later with virtual reality for example, you have many artists who are not working as conceptually. They are just using a tool, in the end. They are making use of the possibilities of a tool that was programmed by other people—software designers and programmers who have basically already laid the foundation for what these artists are able to do in virtual reality. So, we are now at the other end of it. The puristic approach, which I liked so much at the beginning because it was revolutionary, was this idea that art can be totally designed by a program and still be interesting.

In relation to this idea of artists working within someone else’s program, I want to bring up a 2008 interview in which you dismiss Jeff Koonsbecause of his use of Photoshop to design his paintings. You say that you can see the digital aesthetic in the end painting, and suggest that his style was actually developed by Adobe engineers. I’m curious how this idea carries over to virtual reality, at a time when there are really only a couple of ways that you can produce a VR video. To what extent do you see this kind of institutionally imposed aesthetic—if that’s an accurate way of paraphrasing you—as limiting to artists who are working here?

My background is in photography, and if you look at the history of photography you always find the same thing happens with a new medium or new possibilities. People at the beginning are totally excited about what they can do with this new medium. There’s not enough distance from the medium as such. But as soon as you overcome that and you’ve tested the technology, the more interesting work starts to develop. It was the same way with artists who were working with net art in the '90s. At the beginning, net art just involved placing something on a website that had to do with the art or what the artist wanted to communicate. But very soon, the artists hacked the program, and they became aware of the different levels available to net art. Not just the appearance or how you see it on the screen, but also about the levels behind it, the programming languages, and so on. Artists like JODI, by being aware of these levels, started to deal artistically with this medium and make it all their own. They didn’t just accept whatever the rules were, or how it appeared. They interfered with every aspect they wanted to, to get their communication across. And I think that will always happen.

So, you’re not cynical about the influx of artists who are drawn to new technologies, because eventually it gives way to something truly interesting?

Oh, absolutely not. I mean, you can see this already with virtual reality. With how some artists work aesthetically, or how they compose or build the whole thing. They are on totally different levels than others.

If what we’re currently seeing is a burgeoning interest in virtual reality among artists, what are you looking for this time around? What do you think will stick?

Of course there will be a lot produced. I’ve only started to look at this kind of work about two-and-a-half years ago, and I’ve seen quite a lot already. There are many artists who work with virtual reality to some degree, and that will only grow. But I think that once people have seen a few pieces, it will lose some of its interest.

Due to the way you experience this kind of art, you have to get totally involved. It’s very different from looking at a nice picture, or whatever. So, it will become less exciting once it has established itself, and then it will reach into a level where we might find some really great art in this respect.

DAM Gallery will show its first virtual reality exhibit this summer, right? A piece by Banz & Bowinkel.

Yes. The piece was already shown at the House for Electronic Arts in Basel, which is an institution dedicated to new media, and now it’s going to be in a show coming up at the NRW Forum in Düsseldorf in May. Banz & Bowinkel just won first prize for an award dedicated to new media and virtual reality, as well.

What they actually produced is an installation, one you walk into, with pictures, a computer, and of course the virtual reality glasses. The pictures have an augmented reality part as well. There’s also another aspect in how you can influence the daylight of the environment you’re stepping into. And then, when you enter the sphere, they have basically developed seven islands that have different environments, which you can experience by moving into. On one of the islands you can see a video of the outside, and you’re made aware that not only are you in virtual reality, but that you still maintain a connection to the real world. They purposefully confront people with all of these different aspects, so that instead of just being overwhelmed by an exciting experience, the viewer reflects on their levels of perception.

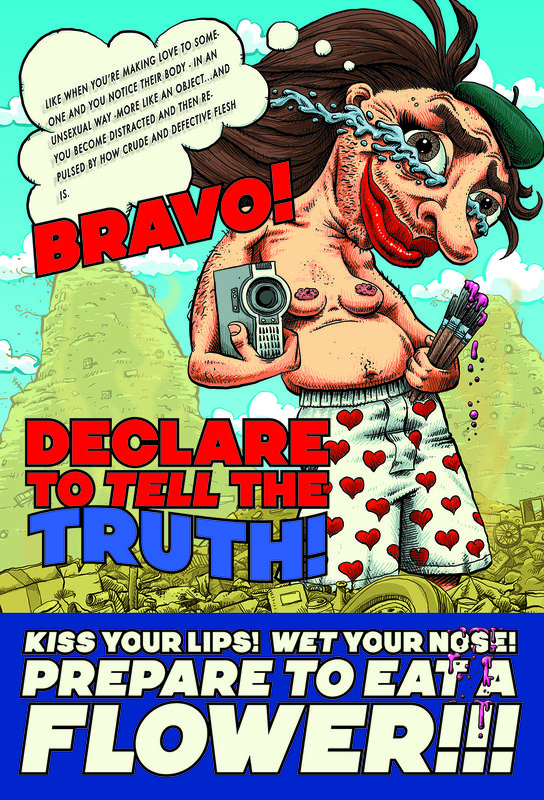

Banz & Bowinkel, installation of Mercury (2016)

Banz & Bowinkel, installation of Mercury (2016)

This kind of conflation of space seems to be something that VR in general is very good at. You can find a lot of VR videos doing similar things in terms of transporting you from one area to another in just a step. Have you found that there are already certain things that VR is inherently good at exploring?

Well, of course there is nothing else comparable in terms of being that immersive. You can’t accomplish that level of immersion with 3D cinema, for example. There’s always an impulse to take the viewers totally out of where they are, and plant them into this kind of artificial environment. This is very tempting and very exciting, but it has a lot of dangers as well. We now have the technological ability to create an environment such that it’s not really disturbing anymore. You can get totally involved with what you’re experiencing.

Speaking of being immersed in disturbing experiences, I’m curious if you had the opportunity to see Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence at this year’s Whitney Biennial when you were in New York, or if you’ve been following all the chatter about it. Do you think it’s an interesting application of this form of digital media, or that it holds up as art apart from its technological aspect?

I’ve just read a little about him in the biennial, but I know about his art and the discussion regarding the design of his puppets. I’m hesitant to talk about a piece I haven’t seen myself, but he seemingly is using the specific characteristics of the medium—full concentration in a secluded space to pull the viewer into a situation that they would normally like to escape. I’m not sure if it goes beyond the actual brutality of the assault. It obviously tries to get as close as possible to real reality, to have a greater effect on the viewer, in opposition to what some artists are trying to do by discovering or enabling new experiences. So far, so good.

What about large, institutional museums in general? Are they responding to virtual reality in a way that you find promising, or that shows an understanding of the promises of the medium?

As virtual reality is very much in its early stages, institutions have to accept that because it’s new, there are not many references yet. What I’ve seen so far has been interesting, but not more than that. It won’t take long until these glasses are wireless, so that you can move around, and then it will really be a great experience. And then, of course, it will open up a lot of possibilities. Then, it will become an old form of expression for artists.

It’ll just be another tool available for use.

In the end, it will be a very, very tiny aspect of contemporary art. Even after all that’s already happened, if you look at the statistics, 80 percent of the art market is still painting.

Even though “painting is dead.”

And there’s still photography and video and more established forms of new media. So, all this will be a very tiny aspect, but it will be an aspect that will grow and that will bring about some interesting challenges for the artists working with it.

Since you mentioned 3D cinema, I want to bring up something that isn’t directly related to digital art, but that I suspect might be helpful in understanding a few things. I keep thinking about Jean-Luc Godard’s most recent film, Goodbye to Language. He basically does everything you’re not supposed to do in 3D, like moving the two cameras far apart, and then too close together. He might show text in only one eye, or a totally different scene in your other eye. It makes you become incredibly aware of how your brain actually works to see, how perception itself is a kind of labor. And in that way the film acts as a sort of training ground for visual literacy. I’ve seen similar things attempted in VR, so I’m curious to what extent you’re intrigued by artists who are working with what you could call “formal” challenges that are unique to certain media.

The reason I got involved with digital arts is that I feel it is very important for artists to undertake aspects that drastically influence or change society. When artists reflect on those aspects, make people aware of them, or just play with them, it can be humanizing. It’s really important to create a distance to it, so people can become aware, as in how you describe Godard’s approach.

Here’s just an idea: You create a totally perfect, simulated environment in virtual reality, and you intersect that with something from the environment the person is actually sitting in. Just by conjoining these things together, you could break this habit that easily develops when you get overly involved in something. I think that is what art should do. It should break habits, or move into directions that you wouldn’t expect.

Casey Reas, Network D (2012)

Casey Reas, Network D (2012)

You’ve been through a lot of the cyclical nature of digital art, and have worked through the rise of net art, Post-Internet art, etc. What’s the purpose of distinguishing digital art now that the internet is accepted as a fundamental part of life?

If you look at the development of new technologies, we are definitely going to see more of a combination between robotic computers and organic body structures. I can’t imagine in detail what that will mean, but I’m sure we will have cyborgs. It won’t happen like we know it from the movies, where with one step we suddenly have half-human, half-machine beings. But realistically, very soon we will have something like a little implant that will help people who can’t hear that well. Then, depending on the combination of normal human life and computer-based possibilities that develop, robots will fulfill different needs to improve the lives of people. And that can go really far, I think. There are many researchers going in very different directions, like some are making little robots you can put into blood and so on. We’ll see all the negative aspects as well, because we might not be able to control them to the degree we would like to.

Every kind of digital file, or any kind of non-material art that can be communicated as digital information, could stand as an idea for our times. An idea for the way we live, how we move around, how we travel, how we can go anywhere and have still have everything accessible on our smartphones. This idea is really a major advantage of this kind of artform.

This sounds like the founding mythology of the internet—as this anarcho-libertarian ideal of a decentralized information network, right? Digital art, and in particular web art, often takes that mythology for granted.

Yes, that’s true. Now that mythology is in danger, because the internet is so dominated by large corporations. This romantic idea about the accessibility of this kind of work was wonderful, but it’s no longer a fact. Even what Google presents to you is based on what you have searched in the past, so you can’t expect to have a really neutral result.

There’s a broad field of artists who are working here. People like Constant Dullaart and other artists have reflected on this kind of mechanism several times, and brought our attention to how these corporations operate. As I mentioned before, I think it’s important that you have artists who are aware of how these things work, who research them and find an interesting way of communicating, so that other people who don’t have the knowledge to really dig in, can start to understand what’s really going on. That’s one aspect of what art can do, it can make people aware of what’s really going on.