There’s a lot of faith and trust involved in what Arlene Schechet does. “It’s like a religious experience,” the sculptor told the New York Times recently.

For the septuagenarian artist, the faith part comes from experience. Shechet has often avoided the impulse to sketch or plan her works. Instead, she prefers to imbue each with the energy of its own creation.

Consequently, her ceramic, steel, wood, and aluminum sculptures often appear to be in motion - divergent, gravity-defying shapes, driven together to unearth the expressive potential of both the material itself - and the human experience.

The New York-based artist says she wants her work “to look like it’s slipping, sliding, and has life.” The text in Phaidon’s forthcoming book, Great Women Sculptors (a wide-ranging survey which champions women sculptors from art history alongside today’s rising stars) eloquently describes a typical encounter with one of her sculptures.

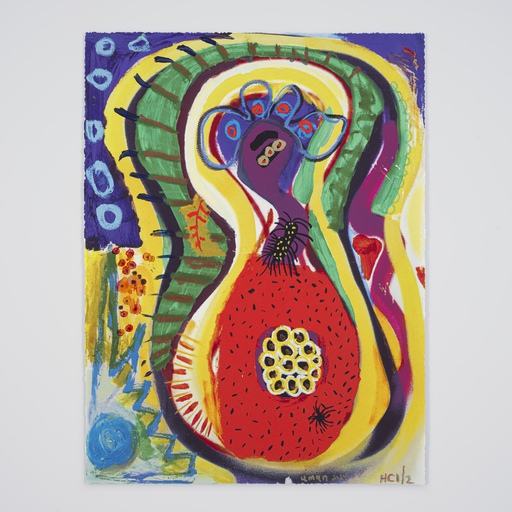

ARLENE SHECHET – New Dawn, 2024

Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

“Forms appear to move with the viewer, as if they are undulating, oscillating, or rotating of their own volition. As the viewer circumambulates the figure, it begins to morph and change, with each different perspective awarding an entirely new experience.”

In common with other artists in Great Women Sculptors it’s been a relatively slow burn for this Pace gallery artist. Since graduating with an MFA in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1978, Shechet has been the subject of many solo exhibitions, including, most notably, All At Once—a 2015 critically acclaimed retrospective at The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, that prompted the New York Times to describe her work as “some of the most imaginative American sculpture of the past 20 years,” and “some of the most radically personal.”

Today, Shechet’s work is held in over fifty public collections worldwide, including The Centre Pompidou, Paris; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California; the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Meanwhile, her current exhibition, the joyfully reviewed Girl Group, at the Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, New York, brings together indoor ceramics pieces with an ensemble of six new outdoor sculptures fashioned from steel and aluminum, each incorporating two colors, shifting from glossy to matte, and including planes of unpainted metal.

Arlene Shechet's Dawn at Storm King, the inspiration for the new edition. Photo by David Schulze courtesy of Storm King Art Center

Arlene Shechet's Dawn at Storm King, the inspiration for the new edition. Photo by David Schulze courtesy of Storm King Art Center

Although the Storm King sculptures are huge, (check out the photos of Shechet working on them here they started small, “germinating”, as Shechet describes it, from clay sculptures she made during the pandemic.

“I just started making these much simpler things and delving back into that. They were on a smaller scale than what I had been working on previously.”

Now, Shechet has chosen to create an edition from the show, in collaboration with Storm King and Artspace. New Dawn , 2024 is an edition of 25 bronze handmade sculptures, 8 inches tall. It is the artist’s first, limited edition sculpture.

Proceeds from the sale of New Dawn, 2024 will support Storm King Art Center’s artistic program and mission to nurture a vibrant bond between art, nature, and people.

ARLENE SHECHET – New Dawn, 2024 Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

Here, in the first of a two part interview with Artspace, she tells us about putting together the Storm King show and how the new edition sprang from one of the sculptures she created for it.

The new edition springs from your current show Girl Group, at Storm King. Tell us a little about that. My idea was threading the sculptures in Girl Group throughout the landscape, not just in a clump but really spread out, so that, in a way, they could speak to one another, but also weave into the landscape and into the conversation with other sculptures by other artists.

I’m typically very critical of my own work, especially when doing a new thing in an extremely public forum. This was not just a new thing, it was six new giant sculptures and then a show inside.

I could sense how the large sculptures would sit and hold up in the landscape but one never knows. In the end it’s all a surprise. In this case a very good surprise. People are seeming to respond, so I’m very happy about that.

Tell us about the planning that went into it. It was almost a two year process. I was very fortunate in that the curator Nora Lawrence gave me the opportunity to site the works myself – to make the first move. Then, if she felt that something might be too close to say a Richard Serra, or too compromising of something already there, she would step in.

Arlene Shechet in the fabrication shop with a new outdoor commission for Storm King Art Center. Photo by David Schulze courtesy of Storm King Art Center

We drove around in golf carts through each season. It’s a large expanse - five hundred acres - so I was trying to find the right spot for things. Then I would stand in each spot to really see. I also used a lot of augmented reality tools where we could actually place the works into the landscape.

We modelled the landscape on the computer and then modelled the sculptures. Then I would bring the iPad with the image renderings to Storm King, and we would site ‘the sculptures’ in the places we had thought about so we could see how they would line up with one another.

That spatial element is so important to your work, how hard was it to get right in such an expansive area? The truth is that five of the six works I felt very happy with. They sat in the landscape exactly the way I wanted and actually were beckoning from acres away to one another. But there was one that I felt was wrong.

So I changed the siting on one of the group of sculptures a week before the show opened. It was a crazy, huge ask, because we had decided in November last year where things were going, and exactly the angle at which they would sit, so that the foundations could be poured in January. That was intimidating!

But I begged, I cried, I did everything to get them to agree that one of them would be better in one spot than the other. Given that five were looking so great I was going to pull out the sixth one if we couldn’t agree, because I didn’t want to wreck it. But they agreed, and we poured the new foundation.

ARLENE SHECHET – New Dawn, 2024

Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

So how did the new edition emerge from the Storm King show? I did small idea models of about three of the sculptures. And then I ended up choosing the work that I had pulled from the large sculpture, Dawn .

It’s called New Dawn , 2024. Dawn is the beginning of everything. I thought that was perfect because it is my first small sculpture relief. It’s a new beginning because it’s a new thing that I’m doing. But I actually chose this relief from the others in Girl Group because I also thought it was the most successful in terms of a sculpture. It has planes, and lines, and texture. That’s almost the whole vocabulary of the large sculptures shrunk into a small, very special thing.

The aluminum sculptures at Storm King are in color but the edition is brass, why did you choose this material in particular? I wanted to point out that brass has color too. And also I wanted to point out that the wonderful thing about sculpture is that it has shadow and light, which makes it colorful within a smaller range, but it still has a great deal of nuance in the way one will perceive what that color is.

It has a warmth to it, is its own thing, and I wanted to do something a little bit surprising. It’s so interesting to do a small sculpture while at the same time doing a very large sculpture. That was the challenge, to be at the poles and do something that felt worthy.

ARLENE SHECHET – New Dawn, 2024

Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

Because most of the materials I work with are living, this edition has change built into it. It will be reactive. It will be a slow transformation and I really love that. It's an engagement. I feel that in all cases it is the viewer who completes the work, so this intimate work can be understood in that way.

I almost wish I could see where it will live in each home. I do hope that people will take the opportunity to experience it as something to place on a table, or their desk, or next to the bed. And then possibly hang it on a different day in a different year. It will survive, and it will survive differently for each person and each place.

And the particularity of this edition is that because all of these things are handmade, each one has a uniqueness.

You’ve previously spoken about how, for you, sculpture is about movement and how the sculpture ‘moves’ around the viewer. How does that perspective change when the sculpture is a smaller edition? I like that question! When I’m talking about the choreography of large sculpture. I’m addressing the notion that - with my sculptures - you can never take it all in. For me, sculpture is always hiding something.

Arlene Shechet in her studio with New Dawn, 2024 - Photography by Chris Roque, edited by Garrett Carroll

I make things that have 360 degree views. So with every step you take you’re going to see that thing differently. And I would say that there is a corresponding idea with making small things, in that you can handle them.

This edition is definitely something to handle . I made it so that it could also just stand and sit comfortably, and it has a lovely weight to it. Gravity is something people talk about seeing or feeling in large sculpture, but I wanted very much to have a sense of it when holding the edition. It’s a satisfying weight. You can feel and experience it’s ‘objectness’, and its material.

It’s yours to touch and it invites that; it can handle that. And also I made it so that it can work effectively when hung on the wall as it were a classic relief, but it also stands.

My feeling is that awareness and consciousness can be piqued by art, and that we can awaken to ourselves and to the world by encountering art, and having it enhance our sensitivity to ourselves and to the world. So if this thing begins to be invisible, move it! Give it another place! Let it be a kind of marker.