There are two sorts of artists in the world, according to Anthony Haden-Guest, who has written about the art milieu for decades in the pages of general-interest magazines and in his landmark 1996 book True Colors, which revealed 20th-century art history to be a riveting maypole of talent, gossip, scandal, and money. The first kind of artist, he says, are those who have all of their raw material by an early age. Many poets fall into this category—say, Keats, Eliot. Then, there is the second, an ungainly breed that bumbles through life, “accumulating other people’s experiences.” He thinks the first makes, arguably, the greatest work. “But the others,” he adds, “are more durable.”

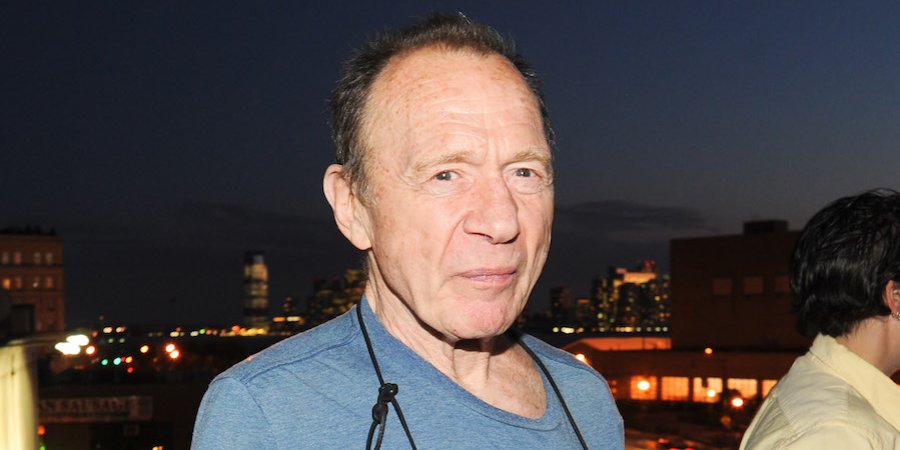

Born in Paris, reared in Britain, and now splitting his time between New York City and London, the septuagenarian bon vivant, in addition to being a writer, is a man of letters and a late-blooming cartoonist. He is the model for Tom Wolfe’s hard-drinking reporter in Bonfire of the Vanities; biologically, he’s the brother of "Spinal Tap" director Christopher Guest. And very likely, he was at the last posh party you attended, scribbling notes in the corner for his long-awaited True Colors sequel. When asked which of his prescribed artistic dispositions he falls into, he coolly ripostes: “Guess.”

Interviewing Haden-Guest, one faces a strong headwind as he deflects questions back with little self-regard, or else skirts personal matters with a polite smile and squint of the eyes. Perhaps that's because beneath the elegant art-world polish is a mind still occupied by the grisly extremes of warfare, the realities of his childhood in war-torn Europe, his early years reporting from conflict zones in the Middle East and Africa. Last week, Artspace's Noelle Bodick spoke to Haden-Guest about why he’s decided to unite these two strands of his experience—art and war—in his new show at William Holman Gallery.

You are a veteran of the art world, not exactly a hardened war vet. What interested you in putting together the show “War Stories,” a survey of depictions of war by contemporary artists?

Well, you know, I’ve been a war reporter. I covered the Biafran War, and the war I covered most was Lebanon. I was there for four years. I mean, this show certainly does not come out of there, but I’ve always been very interested in political extremes.

Right, you were writing about the Lebanese Civil War in the 1980s as well as a working on a book about the narcotics trade. In 1985, you were kidnapped by a Christian rightist group there.

Twice, but once was very short, just for an afternoon. The other time was for 10 days.

What happened exactly?

It was actually slightly intense. But I did not feel like I was a terrible enemy to these people—it had to do with internal clan politics, things of that nature. I was under the protection of one of the major clans over there, and it was another clan that took me. I figured they would sort it out.

You figured they would “sort it out”?

Well, I wasn't that blasé about it. You know, they stuff you into the boot of a car and all that. I have a strange temperament—it has nothing to do with courage. But I can separate myself into two people, perhaps some people know how to do that. There’s the person to whom all these things are happening, and then there’s the other person looking and thinking, “Hmm, this is a tricky situation.”

What drew you to reporting on scenes of warfare?

An interest in living at extremes, actually. At the end, extreme partygoing was not enough. I always regretted not going to Vietnam, for instance. I had a friend who went, a writer, who did some good work, a British guy. I thought, why the F didn’t I do that? I’m very slow sometimes. I was in my early twenties, and it was obviously one of the major experiences of our culture at the time. There was a guy called David Leitch, who’s dead now, who did a wonderful piece, actually, that Tom Wolfe put in his first anthology of New Journalism. I said, “Jesus, damn it, I missed something again.”

So you wish you’d gone for material?

Yeah, material. That’s an art form too: you do what no one else has done or is doing.

It would have been a very different wartime experience than Lebanon.

Yes, I think Lebanon was more predictive of the future than Vietnam. The intense religious animosity there, that was not, in fact, in Vietnam. But in terms of what would come in the world, in geopolitics, it was really fundamental.

Your experience with war predates Lebanon or Vietnam though. Your mother was a Communist who organized wartime escape routes for British soldiers in France during World War II.

My mother escaped from an internment camp with me when I was very young, two. I heard all about this later. It’s been part of my background, and so I guess it has colored my thinking very much. But I don’t want to sound like… you know, I was very young.

What was the point of origin for the show then, if not coming from personal experience?

The genesis of the show was my friend Nin Brudermann, whom I think is a really remarkable artist. In the first piece in the show, there is the same cloud—it was a bombardment—and it seemed like it went on for hours and hours and days. It turned out she had just edited it down to the actual impact. I thought that was brilliant in conveying both the being there and some of the thinking. And I love Trevor Paglen’s work, and then this British guy, Piers Secunda, when he showed me these pieces from the Taliban wars, it was kind of the lightbulb moment. That’s when I thought, “Well, there’s enough work around.”

What is the shared sensibility of these artists?

My main preoccupation was the fact that people are not taking climate change a little bit more seriously, or war, or suitcase bombs. All of the artists take the subject with extreme seriousness, and they are not formally artists. Gregory Green, for instance, is on the FBI list. But I think they all share my own, well, I wouldn't say obsession—I’m not obsessed—but intense interest in warfare as a fact of our lives these days. And I think every one of these artists is driven. You have to be driven to deal with this subject matter, when you're dealing with a subject bigger than one’s self.

You write in the introduction to the show that you believe that there have not been many meaningful visual accounts of war, perhaps discounting photography. Why do you think that the carnage of war has historically been a subject eschewed by artists living through it, maybe Goya and the tradition of history painting aside?

It’s always interested me that the First World War produced some really tremendous figures in art—Paul Nash, people like that—while the Second World War, Hiroshima, and the Holocaust produced really very little. There’s Henry Moore’s wartime sketchbook, but for the most part, we left that all to the photographers. It produced a lot of human anguish, most of which surfaced in writing. I guess you can say German art, like Baselitz and Kiefer particularly, reflect those kind of upheavals, but not in any specific way. I’m not someone who believes that art has to reflect the world. Often the work that reflects it directly is not very good.

Speaking of direct strategies, there is not any photography in the show—there’s no Jim Nachtwey, no Don McCullin.

That was not by design. I wanted a piece by a very great British photographer but couldn't get it. You know, Steven Kasher Gallery did a terrific show of Vietnam photography. What was so strange about that show was how balletic and operatic the pictures looked. They looked like performance art a lot of them—I don’t know if they were curated for that reason.

While not balletic, the work here does share a certain quiet, understated quality. Steve Mumford’s watercolors depict the intermittent lulls between combat in Iraq. Piers Secunda displays abstract plaster reliefs that are in fact the result of Taliban bullets. The work is not particularly visceral. Why do you think that is?

I have not seen any modern Grünewald. You know, Botero made some quite good paintings about Abu Ghraib—I think his best work. But clearly, he was never in Abu Ghraib. Clearly, he had no direct experience of war. Clearly, he was only motivated by the photographs. So I didn't think they belonged in the show. I wanted people who had had direct experience. But it’s an interesting point: writers, photographers deal with this subject. Artists do not. I don’t know why. If I had seen really remarkable work—as I’ve said, a Matthias Grünewald dealing with explosions, severed limbs—I would have been very happy to include it, but I saw no such work. If artists were working using that more visceral and scary imagery we would be seeing it somewhere. There are some human situations that are curiously little-represented: the moment of death, childbirth.

You make this point in the introduction to the show, that the topic of war seems to have been taken up by writers more often than artists. You’ve been on the ground. What are your personal reflections on the matter of writing versus making art about war?

It’s a very interior experience. I think maybe artists require, or prefer, a degree of solitude and focus and concentration. I think a photographer goes “zzzz,” you know, and does his stuff, but an artist doesn't dash to a battlefront and make a painting that matters. I think an artist’s requirements are a little different as a rule.

Just in terms of material restraints?

I think in terms of time, concentration—it requires intense concentration.

Arguably, those are things a good writer needs too.

I think there are essential differences, actually. I can’t really speak for artists, but I think writers can operate in different parts of their mind at the same time. You could have some in-dwelling way of experiencing something and taking it all in. That camera or that tape recorder is working all the time, even when you are having a perfectly ordinary conversation, or hailing a cab, or something like that.

When you were reporting on the war, how did you, as you say, “operate in different parts of your mind”?

It’s actually a bit like making movies. It’s 95 percent of doing nothing at all. You’re just sitting around and then there's five percent of the time when you are just seized by panic and hyperactivity. The worst is when you're stuck in a situation and you're actually not in control, when there are other forces you are aware of. This happened when I was quite young, while I was covering the Biafran War. I was one of the last reporters, and I was stuck there. I was on the Igbo side and the Nigerian army was advancing. There was nothing you could do. We were sitting in the airport. You couldn't see anything, though you heard a few things, I recall. That powerlessness is the worst. As long as you can do something you have the illusion of control, like in gambling.

Is objectivity in reporting on the chaos of war also a kind of illusion of control? You might not be taking action, but you are giving history shape.

When you are a reporter, your job is to be fairly objective. You can only use your own self in limited doses, if at all. So you are forced to exert a great control. It’s not “me, me, me.” It’s, “This went on and that went on, and the other went on.” For war writers, you will find that the events are bigger than they are.

Who are the war writers you admire? Orwell?

I love Orwell. You know, my uncle was killed in Spain—he was a famous Communist. He would probably have been a deadly enemy of Orwell’s, because Orwell of course was a Trot. I love Martha Gellhorn. There are some wonderful writers about war, and they tend to be fairly cool and dispassionate.

Would you say that some of this art in the show here share those same qualities?

Well, it’s not expressionist, you know. It’s compact. It’s not chilly. It’s not without emotion. I think the work does express the times we live in very closely.

Moving from the catastrophic extremes of war to the ruthlessness of the art world, what do you make of the current climate, with hypercharged developments unfolding in the art market?

I think the art world is in a slightly scary place right now in that these mega-galleries have so far not turned much talent in grooming the next generation. I’m not going to name any names. But I like Walter Robinson’s phrase, “zombie formalism.” A lot of that’s around, fetching enormous prices. I’ve never seen so much mediocre work selling at good galleries as I have in the past two or three years.

Why do you think that is?

I think it has to do with this inexhaustible hunger. It’s become a kind of currency, and they need more. There doesn't seem to be the machinery for sorting anymore.

Some of your writing projects have been keeping an eye on where the herd is heading. Where do you think it’s going today?

The art herd? Over a cliff. Isn't that where herds head? Years ago, Robert Hughes, an old grouch, would talk about Tulip mania all the time. It was a favorite metaphor in the ’80s, and people seemed to have dropped that. Today, I think there are lots of reasons for the popularity of art. In timing people at a retrospective at the Serpentine Galleries, the average person was in there for 20 minutes. Now it takes a couple days to read a book. It takes a few hours to see a film. Art is a fairly accessible culture. And you can buy it; you can put it on the wall. I’m being pretty glib and banal here, but I think art has many things going in its favor for the long run. It would be nice to have a few stronger artists around though, younger ones.

You're saying that it is easy to consume.

Yeah.

Should it be easy to consume?

You raise a very fundamental question about what art is for, apart from giving one pleasure. I just read a couple pieces on Carl Andre. Before the Minimalists, people could look at a rusting garage door and think, “Hell, that thing needs a coat of paint.” But then suddenly, thanks to the Minimalists, you look at things differently. And now thanks to the scatter artists, even garbage in the street can look kind of tempting. I think art fulfills that role of making one understand the world a little more. And it’s not just an aesthetic object on the wall, it’s also a way of finding beauty in the real world I think. There’s the 'b'-word.

But what about art about war? Hopefully it is not finding beauty in suffering, not making it easily digested. Famously, Theodor Adorno said that there could be no poetry after Auschwitz, that it would be "barbaric."

Well, he was wrong, wasn't he? There has been a lot of poetry.

Some of the work here in your show is not particularly easy to consume.

That’s good, I think. I find that stuff that’s tougher in the beginning is the stuff that last. The most remarkable example in my recent gallery-going was when I went to Metro Pictures and there was this guy named B. Wurtz. I went in, and at first I thought, “This is silly.” Bits of cloths hung on wire hangers? And then I walked out and then I walked back to have another look and I decided it was wonderful. And it’s a bit tough. Now again there’s something that’s really tough to assimilate.

Have you seen other shows recently that take on big social subjects like war?

There was a show at Eyebeam kind of about climate change, where a group called the Sea Chair Project collected floating plastic in the ocean and turned it into chairs. It felt like a very good idea. That did not play part of my formation of this show, but it was interesting to me. Of course, few artists are dealing with species extinction, I suppose, are they? You know, cloning mammoths and their DNA—as far as I know there is no artist doing that. But all of these things seem to be crying out to be dealt with.

Expert Eye

"True Colors" Author Anthony Haden-Guest Tells War Stories From the Art World