The success of a meme depends on its ability to be easily mutated and replicated by others—rendering the original author obsolete in the process. Viral content is often hard to attribute to a single author, because in order for it to become viral, it needs to be shared by countless users—making it seem as if it simply emerged from collective consciousness. Maybe this is why no one has really stopped to question who (or what) is responsible for a bevy of animal-related viral images and video clips that traveled to just about every corner of the internet over the past few years. There’s what’s become known as “ Pizza Rat ”—a viral video capturing a rodent carrying a slice of pizza down a set of subway stairs; and then “Selfie Rat”—a video that shows, from a distance, a rat crawling onto the phone of a man passed out in the subway, and the subsequent “selfie” the rat captured using the man’s phone. More recently, a meme circulated with the caption “Raccoons are the crackheads of the animal kingdom” above an image of a raccoon standing on its hind legs while riding a crocodile in the water. There’s also the video of a crab disturbingly walking around with a sharp knife in its claws.

A meme via me.me

A meme via me.me

While most of you have likely seen at least one of these videos or images (many of which have been broadcast on national news), you’ve likely never heard of Zardulu the Mythmaker—the prank artist turned “real” artist who recently opened a solo show with Transfer gallery, hosted in a pop-up exhibition in Chinatown as part of the new initiative On Canal, which brings artists, designers, and other creatives into vacant spaces along Canal Street in Manhattan, temporarily. The opening was a “coming out” party of sorts, announcing to the world, or the art world at least, that not only were these viral videos all hoaxes, they were also all orchestrated by a single person—and that that person is an artist.

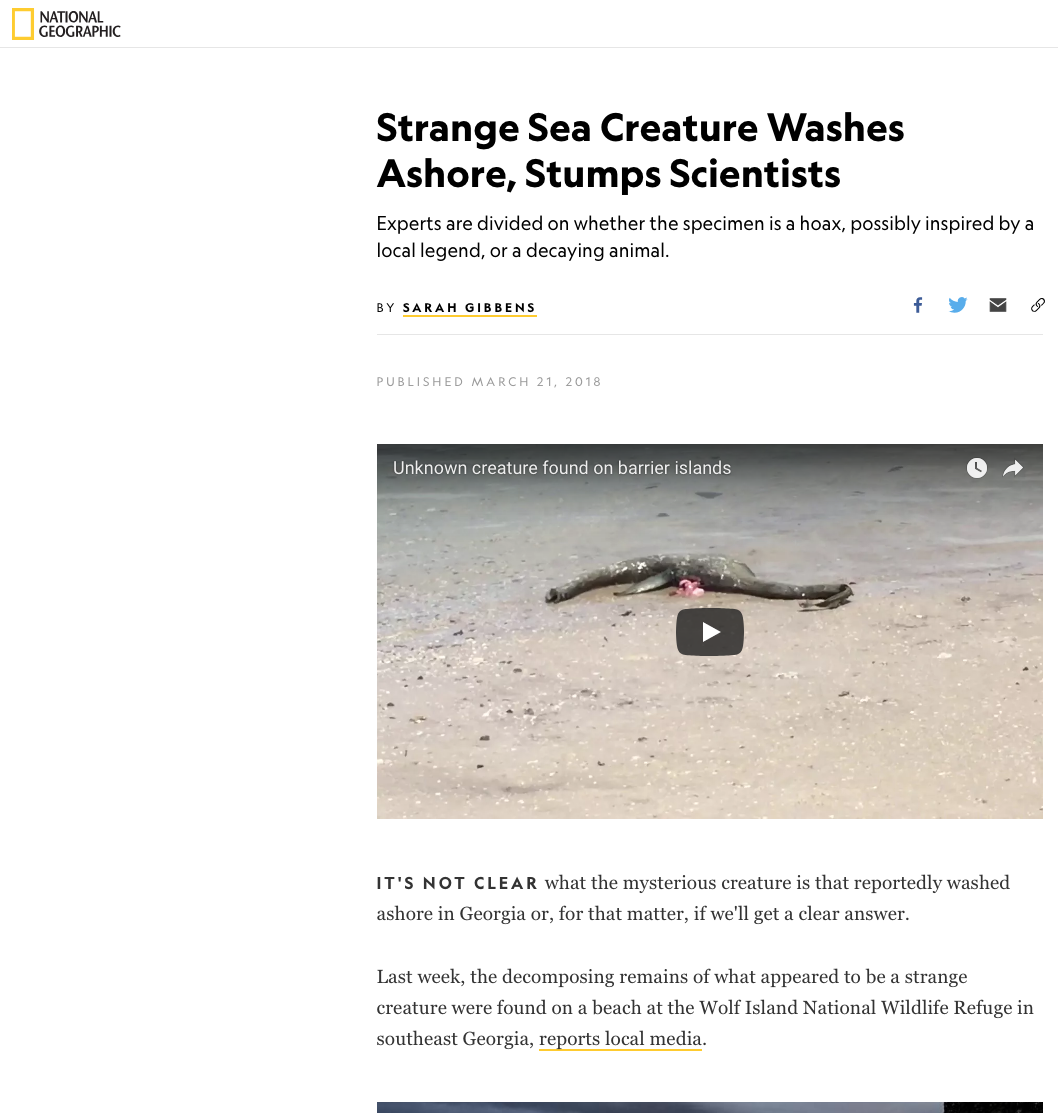

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer is confronted with a large screen populated with a chaotic cascade of images, video clips, articles, and televised news reports that illustrate the scope of Zardulu’s shenanigans. A National Geographic article reports on the supposed carcass of a washed up sea creature with an uncanny resemblance to the Loch Ness Monster. Is it? A newscaster looks alarmed as she describes the alleged three-eyed fish found in the Gowanus canal. And a New York Times report calls a man’s video capturing an iguana crawling out of his toilet during Miami’s Art Basel “one of the most widely viewed pieces during Miami Art Week,” despite the fact that the video wasn’t officially included in the festival. Zardulu’s ability to even pull off some of these stunts is impressive, but what really inspires awe is how massively viral these stories became. Some of Zardulu’s hoaxes became international news stories; “One even trended higher than Trump for three days,” according to Zardulu speaking with Sky News.

Screenshot of National Geographic website, as part of Tranfer's online exhibition in conjunction with the exhibition "ZARDULU THE MYTHMAKER, “TRICONIS AETERNIS: RITES AND MYSTERIES.”

Screenshot of National Geographic website, as part of Tranfer's online exhibition in conjunction with the exhibition "ZARDULU THE MYTHMAKER, “TRICONIS AETERNIS: RITES AND MYSTERIES.”

We are living in the so-called “information age,” though recently it’s felt more like the age of misinformation. We’ve added “fake news” and “false truths” to our lexicon, admitting that truth itself may be socially constructed, and that the building blocks for these constructed truths are the likes, shares, and retweets that give content visibility on the internet. Zardulu’s “fake news” is relatively harmless (if we don’t count the dead animals); they’re politically neutral, innocuous, and non-threatening. But they benefit from the same attention economy that has enabled other myth-makers with very consequential agendas to sway politics and effect lives. The most recent presidential campaign in the U.S. was marred with accusations of “fake news” and Russia’s meddling via social media. But the destructive tactics of online myth-makers didn’t end with Trump’s inauguration.

This past Sunday, far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro—whose long, well-documented history of making homophobic, racist, and misogynistic comments (he once told a female lawmaker that she was too ugly to rape, and that he’d rather have a dead son than a gay son) makes Trump seem like a saint, and who has publicly praised Brazil’s military dictatorship—won 46 per cent of the vote in Brazil’s presidential election, which means he’ll face his opponent, Fernando Haddad of the leftist Workers’ Party (who only received 29 per cent of Sunday’s vote) in a runoff on October 28th. Many warn that the future of democracy in Brazil is at stake, calling Bolsonaro a “facist” whose election would create “a very dangerous situation in Brazil.” Here’s why this is relevant: Steve Bannon, former executive chairmen of Breitbart News and Turmp’s Chief Strategist, is currently working as an advisor for Bolsonaro. And with Bannon’s help, Brazilians have received an onslaught of propaganda, both on mainstream media, and through social media, especially via direct messages on the messaging app WhatsApp. The propaganda spreads the false characterization of Haddad (Bolsonaro’s opponent) as far-left and extremist, when in fact, he’s a moderate progressive candidate. Myth-making, fake news, and online propaganda are dangerous threats to democracy. They're also just plain fascinating.

The Met recently opened an exhibition called “Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy.” It’s no surprise that artists and art audiences find conspiracy and networked myth interesting; and in our current political climate, it’s more ripe than ever to mine for artistic subject matter. But unfortunately, this is not what Zardulu has done. Her exhibition was a missed opportunity to comment on the endlessly fascinating phenomenon of myth-making in the age of fake news. Her online performances, or myths, could have lent themselves to a larger concept or statement, one that uses each viral instance as a way to demonstrate how easily a fiction can quickly become truth—and what’s at stake for society when that’s the case. But instead of utilizing the opportunity of a gallery exhibition to elucidate her previously disconnected online “performances” within a conceptually rich art context, the artist used the gallery space to quite simply manifest her CV as myth-maker as a series literal sculptural representations.

View this post on Instagram

The aforementioned patchwork of on-screen news stories that greets the viewer as she walks into the gallery sets up an expectation. You learn that you’ve been fooled (I honestly thought iguanas coming out of toilets was probably a common Florida occurrence), and that you’ve been participating in a web of lies (however innocuous) that has been spun by a mysterious mastermind artist. So, what is this mastermind's plan? What is her agenda? What does this system of networked gestures say about her perspective as an artist? About the world at large? The reality of the exhibition doesn’t attempt to answer these questions. Populated with pedestals holding taxidermied dead animals arranged in diorama-like displays that reenact each myth in Zardulu’s arsenal, the exhibition is like a coffin that seals off Zardulu’s performances from their audiences/participants as if they were distinct, unrelated gestures ready to be buried—rather than jumping off points to generate discourse.

Zardulu herself made an appearance during the opening, and during an invitation-only “ritual” that unfolded directly after the opening. Adorned in a home-made warlock-esque costume and mask, Zardulu recited archaic excerpts about Hermes, the mythic Greek character with a reputation for being a prankster. Zardulu locates her practice—which, in its purest form is hyper-contemporary, with the potential to distill a highly distinct and poignant moment in our history—within the old, tired, and over-referenced world of ancient Greek mythology. In an abbreviated excerpt from a conversation published in Artnet News in anticipation of the Transfer exhibition, Zardulu speaks cryptically. She exclaims to her interviewer, “Skepticism is such a terrible state of mind, Sarah! Skepticism relates to reason. I relate to unreason.” If there’s one thing our culture doesn’t need more of, it’s "unreason." When asked what we can expect at her upcoming exhibition, Zardulu responds: "Magic." Zardulu’s practice isn’t magic. Myths aren’t magic; they’re created, and usually with agendas. Virility isn’t magic; it’s very real and it’s shaping our politics. Framing her practice within the realm of unreason and magic recklessly undermines the very real and consequential nature of viral myth-making on the internet.

Transfer gallery ambitiously describes itself as “an exhibition space that explores the friction of networked studio practice and its physical instantiation”—a pretty tall order. Art made for the internet is notoriously difficult to exhibit, and we commend Transfer for their dedication to the medium, and for their risk-taking experiments in materializing the immaterial. But some gestures are better left online. Zardulu's gallery show wasn't mysterious like she'd hoped it would be. While revealing the myths she created, she effectively killed the myth, or perhaps the hope, that Zardulu was up to something big, that she had some long-game agenda that would cleverly teach us something about the world in which we live. In this case, the truth was better when it was false.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Why Are Leonardo DiCaprio's Characters Running Around Frieze?

Podcast: Comedian and Performance Artist Alexandra Tatarsky on the Value of Discomfort—And Clowning