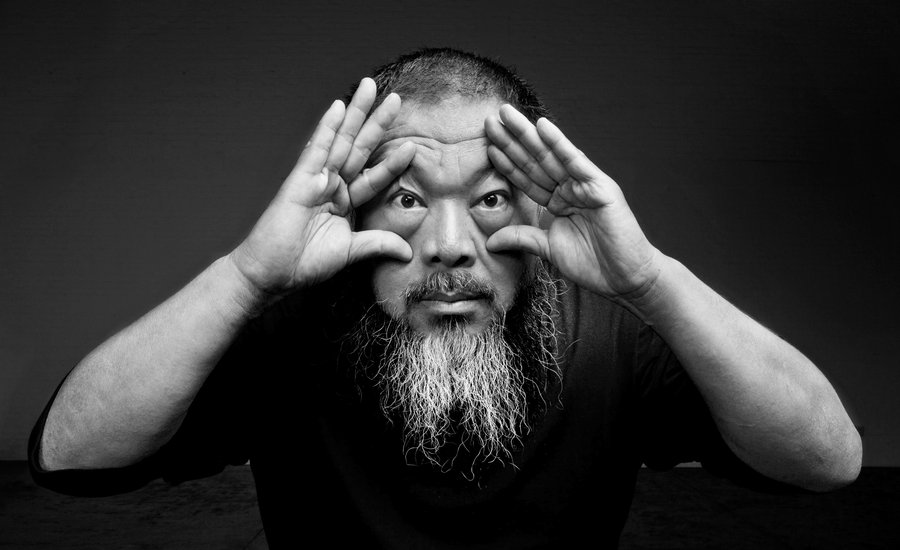

An artist who needs little introduction, Ai Weiwei is unquestionably one of the most important contemporary Chinese artists working today. He’s inspired generations of artists the world over for his dissident political activism as much as his omnivorous approach to art, and, apparently no amount of arrests or censorship can stop him. In this comprehensive interview with the famed “supercurator” Hans Ulrich Obrist excerpted from Phaidon’sAi Weiwei, the artist delves deep into his own origins, detailing the bumpy road to making art history.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Can you tell me about your childhood and how it all started—your awakening as an artist.

Ai Weiwei: Well, I was born in 1957. My father, Ai Qing, was a poet. As I was growing up he was criticized as a writer and punished and sent away to the Gobi desert in the northwest. So I basically spent sixteen years of my childhood and my youth in the Xinjiang Province, which is a remote area of China, near the Russian border. Living conditions were extremely harsh, and education was almost non-existent. But I grew up within the Cultural Revolution, and we had to exercise and study criticism, from self-criticism to political articles by Chairman Mao and Karl Marx, Lenin, and such. That was an everyday exercise and formed the constant political surroundings. After Chairman Mao died I got into film university, at the Beijing Film Academy.

In this province the living conditions were harsh but I suppose because of your father, who was an extraordinary poet, you were also surrounded by his knowledge and literature. How was your relationship with him?

My father was a man who really loved art. He studied art in the 1930s in Paris. He was a very good artist. But right after he came back he was put in jail in Shanghai by the Kuomintang. So while in jail for three years he couldn’t paint, of course, but he became a writer. He was heavily influenced by French poets—Apollinaire, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, you know, all this group of people—and he became a top figure in contemporary language poetry, but even then he couldn’t write, it was forbidden in communist society.

As a writer he was accused of being an anti-revolutionary, anti-Communist-Party and anti-people, and that was a big crime. During the Cultural Revolution he was punished with hard labor and had to clean the public toilets for a village of about 200 people. It was quite a severe punishment for what he had done. He was almost sixty and he had never done any physical work. So for five years he never really had a chance to rest, even for one day. He often joked, he said, “You know, people never stop shitting.” If he stopped one day, the next day’s work would be exactly doubled and he wouldn’t be able to handle it. He physically worked hard but he really handled this job well. I often used to go and visit him at those toilets, to watch what he was doing. I was too small to help. He would make this public area very clean—extremely, precisely clean—then go to another one. So that’s my childhood education.

So no discussions with him about literature and art?

He would often talk about it. You know, we had to burn all his books because he could have got into trouble. We burned all those beautiful hardcover books he collected, and catalogues—beautiful museum catalogues. He only had one book left, which was a big French encyclopedia. Every day he took notes from that book. He wrote Roman history. So he often taught us what the Romans did at the time—you know, who killed whom, all those stories—in the Gobi desert, which is so crazy. Soon he lost the vision in one of his eyes because of a lack of nutrition. But he talked about art, the Impressionists. He loved Rodin and Renoir, and he often talked about modern poetry.

Did your father resume his work later on?

In the 1980s he regained his honor. He was rehabilitated and very popular again. He became head of a writer’s association. And he started to write like young people do, like a younger man. He was really passionate and a very nice man.

Is he still alive?

He passed away in 1996. His illness was what brought me back from the United States in 1993. He passed away when he was eighty-six.

You grew up in the province. Then when you were about twenty you moved to Beijing, where you enrolled in school.

That was right after Chairman Mao died. Nixon had been to China a few years earlier, and they realized they couldn’t survive this communist struggle. You know, the United States were considered as an enemy, but that’s more historical. What really endangered China was Russia, the big bear right above China. Russians and Chinese never trusted each other. So I think that’s why, when Chairman Mao signaled the United States, Nixon and Kissinger had this so-called “ping pong diplomacy”.

After that, in 1976 a big earthquake in Tangshan killed 300,000 people in one night. And the same year, Mao died and three top leaders died—Zhou Enlai and another one. So China was becoming homeless, literally. The ideology collapsed, and the struggle failed and didn’t know where to go. Politically it was an empty space. That’s also the period when I had just graduated from high school. I spent some time in Beijing accompanying my father to treatments for his eye. I started to do some artworks, mostly because I wanted to escape the society. So I had a chance to learn some art from his friends.

Who were these people?

They were a group of literary men or artists who belonged to the same category as my father—they all became what’s known as the “enemy of the state” and then had nothing to do because all of the universities did not open. Many of them are still considered socially dangerous and, like my father, politically still haven’t had a chance to be rehabilitated. Basically they’re professors and very knowledgeable men and literary men or artists, good artists. They had a huge influence on me.

How was it at that time, in the late 1970s, with regard to Western art? What were its influences? Were there books or illustrations?

There were almost no books. The whole nation was to have no single book. I got my first book on Van Gogh, Degas, and Manet and another one, Jasper Johns, from a translator. His name was Jian Sheng Yee. He married, I think, a woman from Germany, and so he had a chance to get those books, and he gave them to me. He thought, “Ah this kid loves art.” And those books became so valuable. You know, everyone shared them in Beijing—this very little circle of artists, everybody read those few copies. It’s very interesting that we all liked the post-Impressionists but we threw the Jasper Johns away because we couldn’t understand it. We asked, “What is this?" and the American flag or a map.

It went into the garbage?

Straight to the garbage. From the education we received at that time we had no clue as to what this was. There was no university education in the Cultural Revolution. They followed the socialist rules, in the Russian style.

There was no knowledge of Marcel Duchamp or Barnett Newman?

No, absolutely nothing. The knowledge stopped at Cubism. Picasso and Matisse were the last heroes of modern history.

Study of Perspective Souvenier Spoons by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

Study of Perspective Souvenier Spoons by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

This is fascinating: there was a limited range of knowledge and hardly any information or books, and yet between the late 1970s and the 1980s there was a dynamic avant-garde in China, of which you were a key protagonist. Somehow, in very few years it went from nothing to everything. What happened during that period? There was no information, there was still a lot of oppression and difficulty, and yet in this resistance somehow an incredible generation formed and became to China what the 1960s generation was to Europe and America, when the Western world experienced this incredible expansion of art at the time—Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys.

I’m very glad you pointed this out. We are a generation that had a sense of the past, which is the time of the Iron Curtain and of the communist struggle. It was a tough political struggle—it was against humanism and individualism and there was, as you know, strong censorship of anything not coming from China. It was even more severe than in North Korea today. The only poetry you could recite was about Chairman Mao. Every classroom, every paper we read was about Chairman Mao, his language and his image. But we all knew what happened before that in the 1920s and 1930s. We all knew about our parents’ fights for a new China, a modern China with a democracy and a science. And then suddenly they had a chance, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, to rethink that part of history.

We started to realize that the lack of freedom and freedom of expression is what caused China’s tragedy. So this group of young people started to write poetry and to make magazines, adopting a democratic way of thinking. We started to act really self-consciously and with a self-awareness to try to achieve this—to fight for personal freedom. It was like spring had come. Everybody would read whatever book they had. There were no copy machines, so we would copy the whole book by hand and give it to a friend. There was a really limited amount of “nutrition” and information, but it was passed on with such effort and such a passionate love for art and rational political thinking. That was the first genuine moment of our democracy.

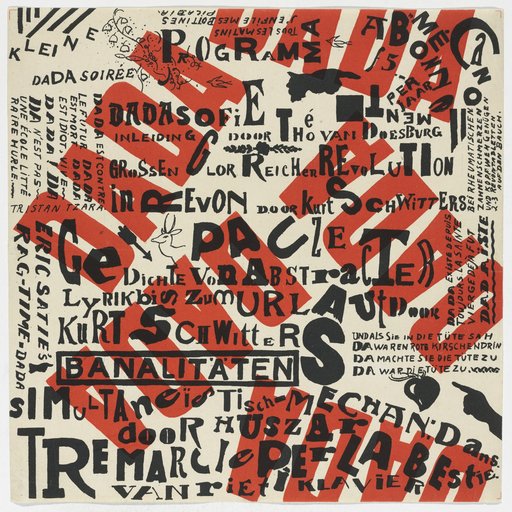

I always felt that it was like a new avant-garde movement, like Fluxus or Dadaism in Europe. How did people meet? Was there a bar or a school?

There was a wall. We called it “the Democratic Wall.” People could post their writings or thoughts on the wall. We used to meet there. And there was a very small circle—China has a huge population, but there were only maybe less than a hundred people who were so active. There were about twenty or thirty magazines we were writing every night, and we had to print them and post them on the wall.

Did you make these magazines yourself?

I did some. I drew a cover by hand for a poet who, at that time, was the best poet. Every cover I drew by hand. So we published books, but then in 1980 Deng Xiaoping came up and repressed the movement. He denounced the wall. He was so afraid of social change—they wanted to have some change, but they didn’t want anybody to denounce the communist struggle.

Did you start to make artworks at the time? What is your very earliest artwork?

I started as a painter. I made drawings, a lot of drawings. I would spend months in the train station because there were so many people there, they were like free models for me—of course at that time there was no model and no school. So I would just stay in the train station to draw all those people who were waiting there.

Do you still have these drawings?

I think my mother threw away most of them. You know, being an artist was not a prestigious practice at that time. I also spent time in the zoo, making very nice drawings of the animals. That was my starting point.

What were your earliest paintings like?

They were mostly about landscapes, in the fashion of Munch—or some were even in the fashion of Cézanne. You can clearly see it. I remember at the end of the school, the teacher would give a critique to every student but he purposely left me alone.

You were in your own world.

Yes, I was very clearly already on my own. I left school before I got to graduate—to go to the United States, in 1981.

What prompted you to go to the United States?

In my mind I already thought New York was the capital of contemporary art. And I wanted to be on top. On the way to the airport my mom said things like, “Do you feel sad because you don’t speak English?”, “You have no money”—I had thirty dollars in my hand—and “What are you going to do there?” I said, “I am going home.” My mother was so surprised, and so were my classmates. I said, “Maybe ten years later, when I come back, you’ll see another Picasso!” They all laughed. I was so naïve, but I had so much confidence. I left because the activists from our same group were put in jail. The accusation was that they were spies for the West, which was total nonsense. The leaders of the Democratic Movement were put in jail for thirteen years, and we knew all these people, and we all got absolutely mad and even scared—you know, “this nation has no hope.”

And so you arrived in the United States. At the time there were very different tendencies—a neo-expressionist, neo-figurative wave and at the same time Neo-Geo and appropriation art. How did you fit into this New York art world?

At the very beginning I studied English. I was so sure I would spend my whole life in New York, I told people this was the last place I would be for the rest of my time, even though I was just in my twenties. When my English was okay, I enrolled in the Parsons School of Design. My teacher was Sean Scully. He liked Jasper Johns, who had just had a show with a series of new works at Leo Castelli at the time. The first book I read was The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: (From A to B and Back Again). I loved that book. The language is so simple and beautiful. So from that I started to know all.

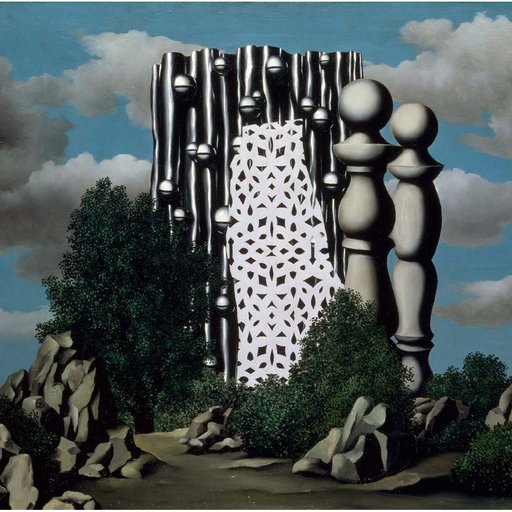

I became a fan of Johns, and then I got introduced to Duchamp’s thinking, which was my introduction to modern and contemporary histories like Dada and Surrealism. I was so fascinated with that period and of course what was going on in New York. It was, as you said, the early 1980s neo-expressionism, which I practiced a little bit but really didn’t like. My mind is more about ideas, so I really liked Conceptualism and Fluxus. But of course at that time it wasn’t popular at home. The 1980s were so much about neo-expressionism. You had to attend those galleries and also the East Village. And there was such a big mix and also a struggle. You started asking yourself what kind of artist you wanted to be. Then Jeff Koons and the others came out with such a fresh approach. I still remember Koons’ first show with all those basketballs in the fish tanks. It was just next door in my neighborhood, the East Village. And I liked that work so much, and the price was very low, 3,000 dollars or something. I was so fascinated by that.

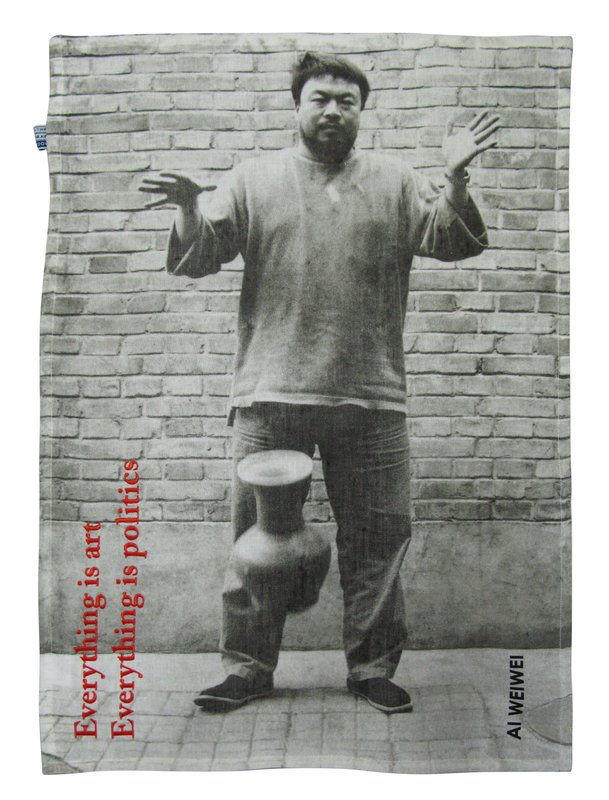

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn - Tea towel, 2013 by Ai Weiwei—available from Artspace

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn - Tea towel, 2013 by Ai Weiwei—available from Artspace

When did you start working with sculpture and installation?

I did my first sculpture in 1983, if you could call it sculpture. Later I used something like a coat hanger to make Duchamp’s profile (Hanging Man, 1985). That time I had already done violins (Violin, 1985), and I had attached condoms to an army raincoat (Safe Sex, 1986). It was about safe sex because around that time everybody was so scared about AIDS. People had just recognized the disease and had more fear than knowledge about it. I really wanted to work with everyday objects—it was the influence of Dada and Duchamp—but I didn’t do much. There are only a few objects left because every time I moved—and I moved about ten times in ten years in New York—I had to throw away all the works.

The violin is interesting because it’s very much related to Surrealism. Does it still exist?

Yes, that’s true. It’s so funny—it’s a commentary about an old time under the present conditions.

You were still painting at that time. There are the three portraits of Mao: Mao 1-3 (1985). When did you decide to stop painting?

Those were the last paintings I did. I did those Maos, and it was somehow like saying goodbye to the old times. I did the group over a very short period, and then I just gave up painting altogether.

How about drawing? I saw a lot of drawings in your studio. Is drawing still a daily practice?

The early drawings I made were more for training myself in how to handle the world with the very simple traces of a mark. That can be enjoyable. I did the best drawings, so even my teachers at the time loved them. They’d say, “This guy can draw so well,” but there is always the danger of becoming self-indulgent. If you see drawings made by Picasso and Matisse, you see they keep drawing because they can just do it so well. I don’t like that kind of feeling, so whenever I begin to feel okay then I try to refuse it and escape from it. Later on I made drawings with different methods. I take photos everyday, which, to me, is just like drawing. It’s an exercise about what you see and how you record it. And to try to not use your hands but rather to use your vision and your mind.

I see you always have your little digital camera with you. You photograph a lot and that’s also a form of drawing, almost like a sketchbook. We could call them “mind drawings.” When did you start taking photographs?

I started in the late 1980s in New York, when I gave up painting. There were only fifty top artists at that time, with Julian Schnabel and those people. I had to attend all those openings and those galleries, and I knew that there was no chance for me. So I started to take a lot of photos, thousands of photos, mostly in black and white. I didn’t even develop them. They were all there until I went back to Beijing. I developed them ten years later. Taking photos is like breathing. It becomes part of you.

That’s like a blog before the blog.

Much later, about two or three years ago, they set up this blog for me—I didn’t even know what to do. I realized I could put my photos on it, so I put up almost 70,000 photos, at least a hundred photos a day, so that they could be shared by thousands of people. The blog has already been visited by over 4 million people. It’s such a wonderful thing, the Internet. People who don’t know me can see exactly what I’ve been doing.

So now it’s basically just a continuum of hundreds of thousands of images, and it’s an ever-growing archive. But do you continue to draw? I’m very interested in the link to calligraphy, this fluid calligraphy, and the kinds of geometry and fragments and the layering and composing of space. Zaha Hadid once told me that there’s really a link between calligraphy and current computer drawing.

Calligraphy is the traces of a mind, or maybe an emotion or thought. Now, with a computer you have photo images, you have the radio. Calligraphy is no longer the matter of hand. I do interviews, hundreds of interviews a year. There are all kinds of sources: newspapers, magazines, television, on all matters—art, design, architecture, social political commentary, and criticism. I think we have a chance today to become everything and nothing at the same time. We can become part of a reality but we can be totally lost and not know what to do.

You mentioned criticism. In your early days writing was very important. You’ve had this link to poetry, and you’re still writing a lot.

I like writing the most. If I have to value it against all human activities, writing is the most interesting form, because it relates to everybody and it’s a form that everybody can understand. During the Cultural Revolution we never had a chance to write, besides writing some critical stuff, so I really like to pick up on that, and the blog gives me a chance. I did a lot of interviews with artists, just simple interviews. I asked about their past, what’s on their minds, and I also wrote. So in the blog I did over 200 pieces of writing and interviews which really put me in a critical position—you have to write it down, it’s black and white, it’s in words, and they can see it, so you really have no place to escape. I really love it, and I think it’s important for you, as a person, to exercise, to clear out what you really want to say. Maybe you’re just empty, but maybe you really have to define this emptiness and to be clear.

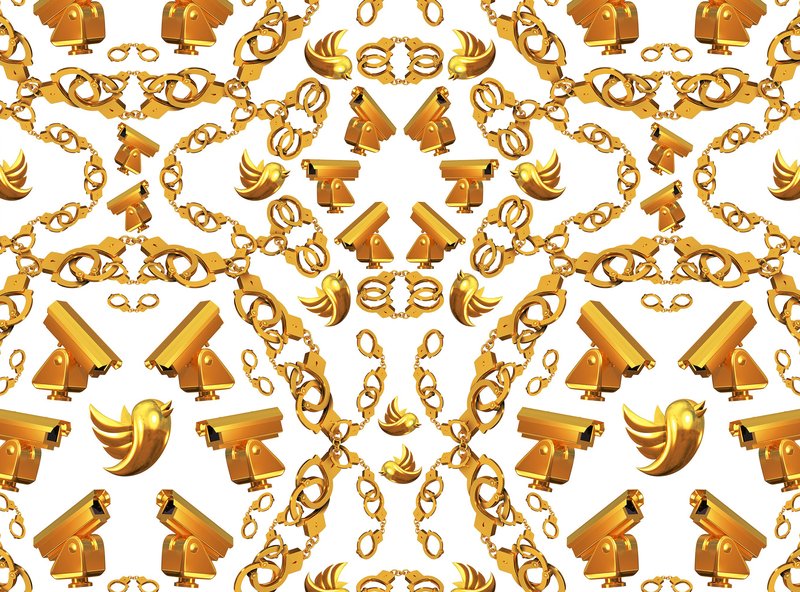

Golden Age by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

Golden Age by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

Your blog and your work make a lot of things public. Do you have any secrets? What is your best-kept secret?

I have a tendency to open up the personal secrets. I think, being human, that both life and death have a secret side but there’s the temptation to reveal the truth and to see the fact that you need some courage or understanding about life or death. So even if you try to reveal or open yourself, you’re still a mystery, because everybody is a mystery. We can never understand ourselves. However we act or whatever we do is misleading. So in that case, it doesn’t matter.

Now, we’re still in New York, we are in the 1980s, and at a certain moment you decided to go back to China. Was that a planned decision or did it have to do with, as you said, your father getting ill? I spoke to I. M. Pei, who said that when he left for the United States it was a departure without return. He became an American architect and didn’t go back. So what about this idea of exile—temporary exile or permanent exile?

I stayed in New York. I gave up my legal status because I knew I was going to stay there forever, so I become an illegal alien. I tried to survive by doing any kind of work that came to hand—I did gardening at the beginning, and housekeeping. At that time my English was quite bad. Then I did carpentry, I did framing work, I had a printing job, I did all sorts of work just to survive, but at the same time I knew I was an artist. It became like a symbolic thing to be “an artist.” You’re not just somebody else, but an artist. But I wasn’t making so much art. After Duchamp, I realized that being an artist is more about a lifestyle and attitude than producing some product.

More like an attitude?

More like an attitude, a way of looking at things. So that freed me, but at the same time it put me in a very difficult position—I knew I was an artist but didn’t do so much. So the few works we see today are probably the only works I did. I was just wandering around. I didn’t have much to do. And after a while it became very difficult, because I was so young. On the one hand you want to do something, to be somebody, but at the same time you realize it’s almost impossible, economically and culturally. It was an excuse for me to go back to China and to take a look, because for the past twelve years I hadn’t written back home and had never visited. I didn’t have a good relationship with my family. There was some distance. The question was, if I had to go back, this was the moment. So in 1993 I made a decision and just packed everything and moved back.

How did you find China changed?

1989 was the crackdown of the student movement—Tiananmen. I had no illusions about China, even though everybody told me that China had changed so much and that I should take a look. Some things had changed, some things hadn’t changed. What changed was that there was more beauty in the center. It was a little bit looser about the economy. There was little bit of free enterprise, but there was still a strong struggle, the ideology. And what hasn’t changed is the Communist Party—it’s still wide, still kills today. There’s still censorship, there’s no freedom of speech, just the same as when I left. It’s crazy. It’s really such a complex set of conditions. And you realize the society has so many problems and the change is so small and so insignificant and so slow. After I got back, I still felt there wasn’t much to do there, so I started working on three books.

That’s the beginning of your famous books.

Yes. The Black Book (1994) is the first one, then the White (1995) and the Grey (1997).

I saw them in an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London about design in China. They’re almost like cult books now.

There are so many artists who have been influenced by those three books, and so I tried to make a document or an archive for what was going on, and at the same time to promote a conceptual base for the art rather than just art on canvas on easels. So I forced artists to write a concept, to explain what is behind their activity. At the very beginning they were not used to it, but some knew how to do it. I also wanted to introduce Duchamp, Jeff Koons, and Andy Warhol and some conceptual artists and the essential writings, to China.

Was this the beginning of your curatorial endeavor? You could say these books are also curatorial projects and that you’ve curated ever since.

Yes, it’s curatorial. So around 1997/98 we created this China Art Archives and Warehouse, the first alternative space for contemporary art in China. Before that all the works were sold in hotel lobbies, and framing shops were just for the tourists and foreign embassies. So we did it and tried to justify the space and the institution to show what was happening. And then later, by 2000, I curated another show, “Fuck Off,” in Shanghai. I think we met before that.

Yeah, we met for the first time in the late 1990s.

At that time you were so young and so fresh, and I still remember the evening we were in an artist’s home, I think—many people gathered to see you.

I remember. That first trip was essential to me. I’d like to stay a little bit more with the Black, White, and Grey books. Looking at these books today they appear like avant-garde manifestos, to some extent. We live in a time where there are fewer manifestos. Dadaism and Futurism, for example, both had manifestos in the early twentieth century, but still in the 1960s there was this whole new avant-garde idea—Benjamin Buchloh always spoke about the whole idea of the manifesto. Do you think there is still space for this kind of movement?

I think art always has a manifesto, any good art, as with the Dada movement or early Russian Constructivism or early Fluxus in the 1970s, all those things that people did. It’s an announcement of the new, an announcement to be part of a new position or a justification, or to identify the possible conditions. I think that’s the most exciting part about art. Once you make a manifesto you really take some risks. You have to put yourself in a condition. You have to be singled out because it’s the nature of the manifesto.

In architecture, manifestos are a very different thing. You started, at a certain moment, to venture into architecture. Did it begin in America or did it start when you went back to China? When I met you in the 1990s you were already in a double practice—as both artist and architect.

I didn’t start consciously. I remember two instances I had with architecture. First was discovering Frank Lloyd Wright, only because he did the Guggenheim, and that beauty we hated because,you know, no painting could be hung there. That was then, but now I think it’s very interesting. It’s just like a parking lot type of thing.

The second was when I bought a book by Wittgenstein, the writer philosopher. He did this building for his sister in Vienna. I saw that book and thought, “Oh, this guy can build a house for his sister,” so I bought that beautiful book. Those are the only two instances in New York that I had a relationship with architecture. After I came back I lived with my mother in Beijing. In 1999 I decided to have my own studio. So I walked into this village and asked the owner of the village if I could rent some land. He said, “Yes we have land,” so I said, “Can I build something?” He said, “Yes, you can build.” It was illegal, but they didn’t care. So I rented the land, and one afternoon I made some drawings, without even thinking about architecture. I just used pure measurement for the volume and proportions and put in a window, a door. Then six days later we had already finished it, and then I moved in.

This was the time when China started to build a lot, but many of the buildings were very commercial and came from just one single kind of practice. So a lot of magazines noticed, “Oh, we can build differently, here’s this guy who builds with very limited resources, for a very low price, by himself.” It became a very widely exposed building in China. People started asking me to do work for them, some big commercial projects. So I decided, “This is so simple. You just use your common knowledge and you don’t have to be an architect to build,” because I think that the so-called “common knowledge” and everyday experience are so lacking in academic studies. I had a chance, and I had nothing else to do, so I started a practice. I formed this company, FAKE Design. In China the word “fake” is pronounced, “fuck.” We have done about fifty projects in the past seven years. All kinds of projects, from urban planning to interior design.

Most of them are built, right?

Ninety per cent of them are built.

You have built more in nine years as an artist than many architects in a lifetime.

Yes, it’s true, we build more than most architects in their lifetime.

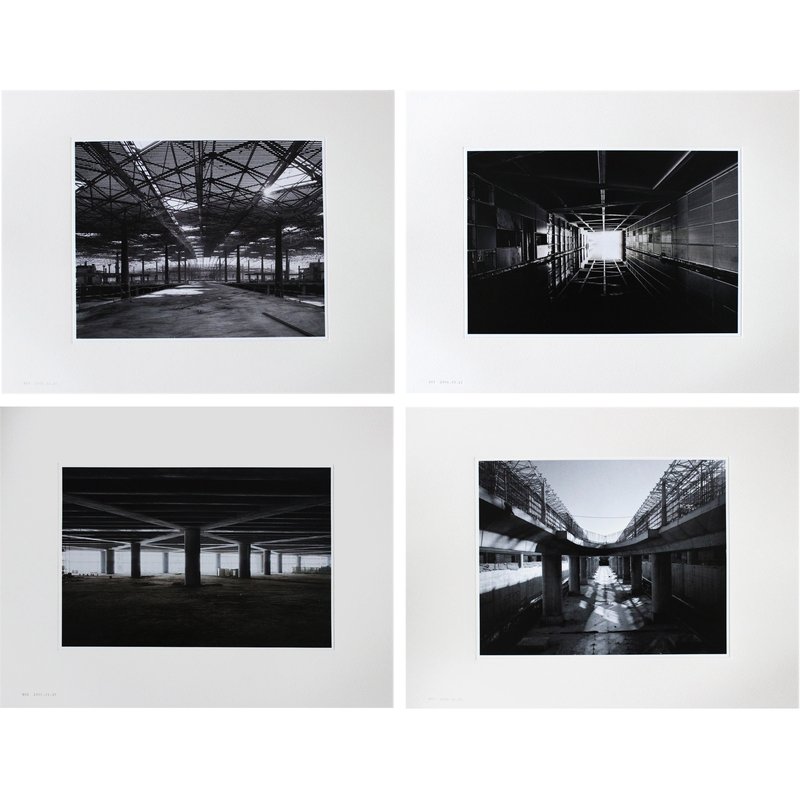

Untitled (from Becoming series), 2009 by Ai Weiwei

Untitled (from Becoming series), 2009 by Ai Weiwei

What an achievement. But not only have you built a lot, but you have also curated the most visionary architecture projects. When we spoke last time for Domus you were curating an architecture village, almost like Weissenhofsiedlung from the 1920s in Stuttgart, in which modern architects build a street. Now you’re working on an even bigger architecture project involving one hundred architects. Could you talk a little bit about this? Curating architecture is very different from curating art. Curating architecture is production of reality.

Yes, I love the words “production of reality.” Architecture is important for a time because it’s a physical example of who we are, of how we look at ourselves, of how we want to identify with our time, so it’s evidence of mankind at the time. After the first venture into architecture, I fell very much in love with this activity. It relates so directly to politics and reality. Then I realized that it’s very important for China and for the world to be introduced to each other. So many young architects are produced in the West but have no chance to build their work, and their knowledge can never be exercised.

Education itself has failed because you only just theoretically talk about architecture, and this becomes another kind of architecture. I thought it would be best to have them take part in global activities, the reality. Also in another way it is important to balance the view of architecture. It’s not just education through the examples of so-called masterpieces. It’s also the study of real locations, real problems, and needs to include the undesirable conditions like high speed or vast developments or low-cost architecture. I think those are important factors of architecture but aren’t always being consciously brought out.

Low-cost architecture—that’s like low-cost airlines.

Yes, or rough architecture, which is fine. It’s all about human struggle and the reality of the condition rather than being a utopian thing. That’s why I try to curate the architecture projects, to try and bring as many young people from all over the world as possible, because they all want to exercise their own mind and their own problems. The problems are their own problem. Any problem is everybody’s problem, so you just have to participate. And if you have no chance to participate, this is a pity!

So that leads to your biggest project, the one with one hundred architects in Mongolia.

Yes. A developer asked me to help build this town in Mongolia. They said, “We think you’re the one that can make things happen.” I said yes. I thought about it because I had announced that I would totally give up architecture because I had so much work to do. But I thought, “Okay, I can do it, but only if I’m in the position of curating it, because I don’t care if I actually build one myself. I don’t have that ego anymore, but I know many great minds, young minds, who would love to do something and this is the chance.” So he understood me. He said, “Whatever you say is fine.”

So I asked Jacques [Herzog] and I said, “Jacques, you know this is a big project, but your participation is to give me the list of names.” And Jacques understood immediately. I don’t think it required much explanation. Soon after, he provided a list of names. So we contacted those one hundred people, and they all agreed to come.

What a miracle!

I think finally we realized this kind of miracle can happen in a short period of time, and I do have an impact, not only for those architects who are participating but also for the people of the world to see the possibilities. I think that’s what’s good about it.

When I was looking at your book Works 2004-2007 last night I became aware once more of all the different production practices present in your work. We’ve spoken about architecture, we’ve spoken about curating, and we’ve spoken about your sculpture and installations. There are so many fascinating aspects that have started to unfold over the last couple of years. I remember two years ago I saw Bowl of Pearls (2006) for the first time in your studio. We are living in the digital age, when we’re accumulating more and more archive material but not necessarily memory. A lot of your works are about memory, and there is Coca-Cola Vase (1997) but then at the same time there is also the work with furniture, like Table with Two Legs on the Wall (1997), which revisits memory in an interesting way. Could we talk about memory? Eric Hobsbawm was saying to me the other day that we should protest against forgetting.

Yes, because we move so fast that a memory is something we can grab. It’s the easiest thing to just attach to during fast movement. The faster we move, the more often we turn our heads back to look on the past, and this is all because we move so fast. The work in the catalogue may be just one tenth of my activities. On the one hand I take art very seriously, but the production has never been so serious, and most of it is an ironic act. But anyhow, you need traces, you need people to be able to locate you, you have a responsibility to say what you have to say and to be wherever you should be. You’re part of the misery and you can’t make it more or less. You’re still part of the whole fascinating condition here. I work now in a different sense, but it’s really just traces. It’s not important. It’s not the work itself. It’s a fragment that shows there was a storm passing by. Those pieces are left because they're evidence, but they really cannot construct something. It’s a waste.

A waste? Because you call them fragments, these are fragments, no?

It’s weird, because you call something something else. For example, an old, destroyed temple: you know the old temple was beautiful and beautifully built. We could once all believe and hope in it. But once it has been destroyed, it’s nothing. It becomes another artist’s material to build something completely contradictory to what it was before. So it’s full of ignorance and also a redefinition or reconsideration. All those Neolithic vases are from 4,000 years ago and have been dipped into a Japanese-brand industrial household paint, and they become another image entirely, with the original image hiding in thin layers (or thick layers) of this paint. People can still recognize them, and for that reason they value them, because they move from the traditional antique museum into a contemporary art environment, and they appear in auctions or as some kind of collector’s item.

Besides the fragments and the waste, a sort of monumental junkyard piece here plays a role. At Documenta, seeing your Fairytale (2007) and looking at your blog, increasingly I came to think that your blog is actually a social sculpture in a Joseph Beuys kind of sense. Do you see yourself as a social sculptor, and is there a link to Beuys?

I think you’re the first one who has recognized that in the digital age virtual reality is part of reality, and it becomes more and more influential in our daily lives. Think about how many people use or are addicted to it. And of course all activities or artworks should be social. Even in the medieval age they all carried this message of a social and politically strong mind. From the Renaissance to the best of contemporary art, it’s about, as you said, the manifestos and our individuality. Especially today I think it’s unavoidable to be social and political. So in that sense I think Beuys made a very good example to initiate his pupils. I know very little about Beuys because I studied in the United States, but Warhol did it in his own ways: his factory, his announcements about “popism," about portraits, about production, the interviews he did—nothing could be more social than that, I think.

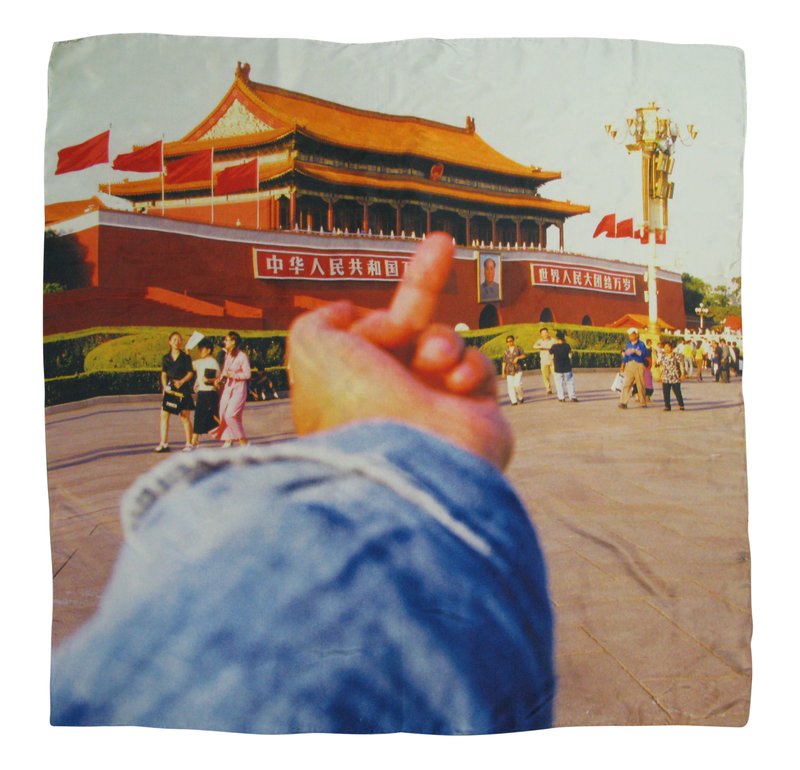

Study of Perspective - Tiananmen - Scarf, 2013 by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

Study of Perspective - Tiananmen - Scarf, 2013 by Ai Weiwei—available on Artspace

Now we’ve spoken a lot about your manifold projects, but what we haven’t spoken about is my favorite question, your yet-unrealized projects. I think I’ve asked you before, but I think I’ll have to ask you today again. What are your yet-unrealized projects?

I think it would be to disappearing. Nothing could be bigger than that. After a while everybody just wants to disappear. Otherwise, I don’t know. So far, practically speaking, I will have a show in Haus der Kunst in Munich next year, so I have to prepare for that and several other shows. I don’t know. I don’t know what’s going to come out, how it’s going to be handled.

Dan Graham once said that the only way to fully understand artists is to know what music they listen to. What kind of music are you listening to?

I don’t listen to music at home. I have never in my life turned on music. I’m not conscious of music. I can appreciate it, I can analyze it, and I have many friends in music, but I never really turn on to music. Silence is my music.

What is your favorite word?

My favorite word? It’s “act.”

What turns you on?

The unfamiliar reality. The condition of uneasiness.

What turns you off?

Repetition.

What’s the moment we are all waiting for?

The moment where we lose our consciousness.

What profession other than yours would you like to attempt?

To live without thinking about professions.

Hypothetically, if heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive?

“Oh! You’re not supposed to be here.”

[related-works-module]