When it comes to large-scale artistic interventions into the natural world, the movement that usually leaps to mind is Land Art—huge, muscular sculptures carved or pulled from the earth by heavy machinery at the command of men like Robert Smithsonand Walter De Maria, self-styled “gruff individualists” who claimed the studio and gallery were simply too small to contain their big ideas.

There is, however, another tangent of this impulse to work directly with the natural world, albeit one that tends to get lumped in with Land Art, or left out of the conversation altogether: ecological or “Eco” art as exemplified in the work of Agnes Denes, who since the late 1960s has been quietly at work imagining new ways to engage with the environment and its human inhabitants. In place of massive monuments to (usually one) man’s ingenuity, Denes creates webs of interrelation between living things, forests, fields, and parks that serve as sites for human contemplation as well as functioning ecosystems. It’s a complex form of art-making that's both highly conceptual and technically challenging, and one that—despite Denes’s sustained effort to bring her ideas to the public for decades—is only now winning widespread acceptance within the mainstream art world.

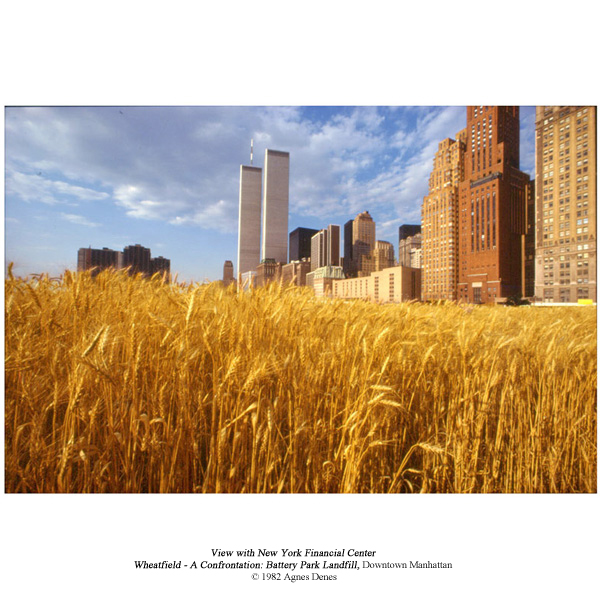

While you may not know her name off the top of your head, you’re probably aware of at least one of Denes's works: Wheatfield - a Confrontation, the 1982 piece in which the Hungarian-born, New York-based artist planted two acres of wheat in a landfill neighboring the World Trade Center and Wall Street. (The site is now Battery Park City.) It’s a seemingly straightforward piece, lasting only the six months it took to grow and harvest the wheat (all 1,000 pounds of it), but, like much of Denes’s work over her 50-year career, its apparent simplicity hides the heady ideas (and hard physical labor) at its foundation.

Her aim, throughout her ecological work as well as the writing and drawings she calls her “Visual Philosophy,” is to give form to ideas and processes that are normally beyond the range of human conception, with the vagaries of time and the interconnections between human societies and the natural world at the fore. If Land Art was about exerting sometimes extreme force to make your mark on the landscape, Denes’s art about exploring how more delicate (if no less jarring) gestures—made with the natural processes of birth, growth, and death in mind—can create lasting and poetic impacts that play out over an ecological, rather than merely human, timescale.

At 85 years old, Denes doesn’t want for self-confidence; as she discusses in our interview below, she sees her work as an important milestone in the context of 20th-century art history that is overlooked in favor of more readily graspable concepts and manageable endeavors (not to mention pieces that don’t require months or years to be fully appreciated). Though the conversation steers clear of current events, careful readers will nevertheless be able to discern an ethos of environmentally conscious communalism peeking out around the edges of Denes’s words—a perennially important ideology to hold onto, especially in uncertain times like these.

You’ve worked extensively with the natural world under the banner of what’s now called “Eco Art” since the late '60s. How did these concerns become so central to your work?

That’s a good question, but it has to be approached from another angle. I started out as a poet, but I "lost my language," so to speak, after here coming from Europe. You can’t write poetry from another tongue, unless you are bilingual from birth.

I gave up poetry and saw myself as having become deaf and dumb. It was like being silenced. But you can’t stop creativity—it bubbles up—so I started becoming creative in a visual form instead of the verbal. I went through a creative process to see where I fit in visually.

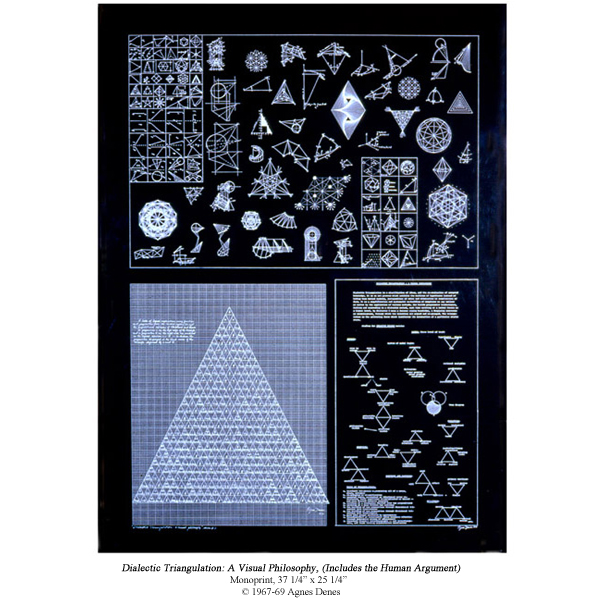

After a while I realized that this was not answering the questions in my mind. I decided that I was going to use a different approach and bring my knowledge of philosophy and science into my art. I assumed that I could tackle something as large as re-evaluating human knowledge. I spent my life in the library, going through one discipline after another and doing tremendous amount of research. From that new research was born my “visual philosophy," where I put into visual form mathematics, logic, thinking processes, time, et cetera. It was extremely challenging.

What was the impetus for putting those abstract ideas into visual form? Why did you feel that was so important for you to be doing?

What’s the impetus for any creative process? It bubbles up from inside you. I’m still doing creative work, in spite of physical ailments and my age. You can’t stop that. And all the while I also kept writing books—probably the aftermath of having been a poet and writer before.

Book of Dust was the result of 16 years of research spent reevaluating all of human knowledge. Few people are even aware of its importance. I was told that I should have things in it patented, such as my concept of the universe, the future of the universe, the brain, or time. Never bothered doing that. Of course it’s out of print, like most artists’ books. It’s a seeking of essences, a summarizing in the face of extensions arrived at from the influence of specialization, but that’s another story.

I did all my drawings—beautiful, intricate drawings—by hand. I didn’t use the computer, which is now looked at as the way to do everything. I did one drawing that had 1,300 little people in it, all by hand. It’s now going into the New School as a 40-foot mural. The students may wonder what program I used to make them—they can only think in terms of programs. I show them my two hands. Now that I lost movement of my fingers due to this illness and couldn’t do those beautiful drawings any more, I began creating art in the computer. I taught myself. You can’t put a lid on creativity.

So how exactly did ecology come into play in your work?

When I realized that two-dimensional art was not enough to express all I wanted to say, I “got off the wall,” as I usually refer to it, and stepped into the three dimensional environment. Well, four dimensional if you want to be exact. That was the birth of my environmental art and the basis of all my work.

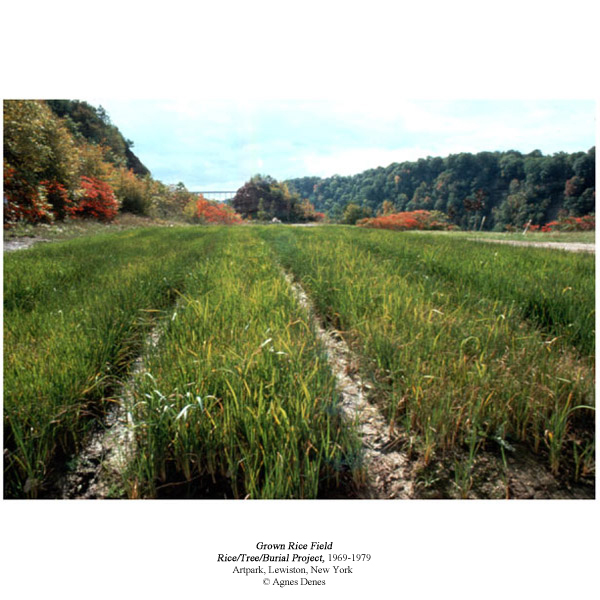

I made the Rice/Tree/Burial, acknowledged as the first large-scale environmental or ecological art project, in 1968 as a ritual and then recreated it at the invitation of Artpark in 1977-1979.

That’s also around the time that the Land artists were getting underway. How do you see yourself in relation to that movement, with which you’re not often aligned?

That’s an interesting point, and I’ve been interviewed about that many times before. Land Art is not environmental art and people are now beginning to realize that. It’s actually about using more space. Land artists wanted more space than their studio—they weren’t interested in ecology. It wasn’t in the vocabulary in those days. It was in mine because I was writing a book about it at the same time, the Book of Dust.

It’s a totally different approach, and they were all men. They would not allow women in their group, if any even wanted to be there. Land Art is totally different, even if sometimes it’s lumped together with environmental art and ecological art.

They have totally different relationships to the environment—one is about exerting power, the other is about working with these natural forces.

Now it’s beginning to be understood, but it wasn’t at the time. They used the land, and I am calling attention to the land, to the power of the land, the power of the seed. My thoughts are the seed I plant in people’s mind.

You know, I would need about 500 years to do my projects. There’s just so many of them. One of the books I’m writing is titled Unrealized Projects. If I could have completed those projects—I mean, my God. I realized not even 1/100 of my concepts, and look how people love them, the wheat fields and the forests all over the world.

And those are just the ones I was allowed to do—you need permission to do things in the environment. You need to be commissioned, you need funding. I designed mega dunes after Sandy hit to protect the shores from the onslaught of water. Where did it go? The powers to be didn’t allow me to realize it. The next time it comes, we’re going to be inundated again. I’ve also designed the Forest for New York, which would be an important project for the city.

What does that consist of?

I’m trying to take 127-acre site here in New York—in Queens—and make it into a forest and an environmental project where people can come to plant their own trees, become involved with the environment, and have celebrations. I’m still trying to get hold of the site, dealing with a lot of confusion and doubletalk.

That’s one big problem: when you make art in your studio, you do what you want. Nobody can tell you what to do. You can use your imagination and your talent. When you go out in the environment, everybody will tell you what to do. Everybody is your boss. I’ve been working on this forest for two and a half years now.

New York does need a place like that. It’s a beautiful site, a landfill. I’m the master of landfills! Whenever there’s garbage, they give it to me. Actually, I did a lot of study on landfills around the world and how you can fix them for varied use.

Of course, the piece you’re best known for also took place on top of a dump: Wheatfield – A Confrontation, in the Battery Park City landfill here in New York. What was the artistic climate like when you started working on that project? How was it received at the time?

Doris Freedman started the Public Art Fund. She was a wonderful woman and she loved my work. The Public Art Fund invited me to do a sculpture in a park—I wanted to plant a field of wheat instead. And she said to go ahead and do it.

They first wanted to first put me in Queens. Doing a wheat field there would not have had the power that a wheat field had two blocks from Wall Street and the World Trade Center facing the Statue of Liberty. It had to be positioned there for the power of the message. I held out, and it took about a year until I got the site.

Now I had four acres of Manhattan that were mine, for a while, but no money. The Public Art Fund gave me $10,000 to do the project—one of the best known public art projects in the world was done on a tiny budget. Of course, it took more of my own money and donations such as free labor. Just bringing in the soil I needed to put down on the landfill would have been like $20,000, and I had no money for assistants. I had to call every single day, getting people to volunteer. I made sandwiches to pay them for the work. It was an agonizing, magnificent project, what they call the agony and the ecstasy.

It seems that these kinds of large-scale ecological projects are often huge undertakings that don’t have a ton of money pouring in to support them.

But there are people who manage to get money for their work—I was never able to do that. I respond to what comes to me, but I’m not good at reaching out and making things happen.

While ecological art may not be what you would call a popular art form, in the years since you started working with it in earnest it has certainly become an approach that is perennially put forward and explored. There’s always a crop of new people who are looking for different ways to explore similar situations. What do you make of contemporary eco art?

Well, I’m proud of the movement I started. I did Rice/Tree/Burial in 1968, not thinking of any movement. It was philosophically oriented, as all my work is. I called it Philosophy in the Land.

When I started it, people said, “What? She’s crazy. What is she doing? It’s not art.” Now I love that so many people want to do this type of work. Its time has come.

Working with living things—from individual trees to whole ecosystems—brings with it a host of challenges that most artists never have to consider. What are some of the issues you’ve encountered over the years?

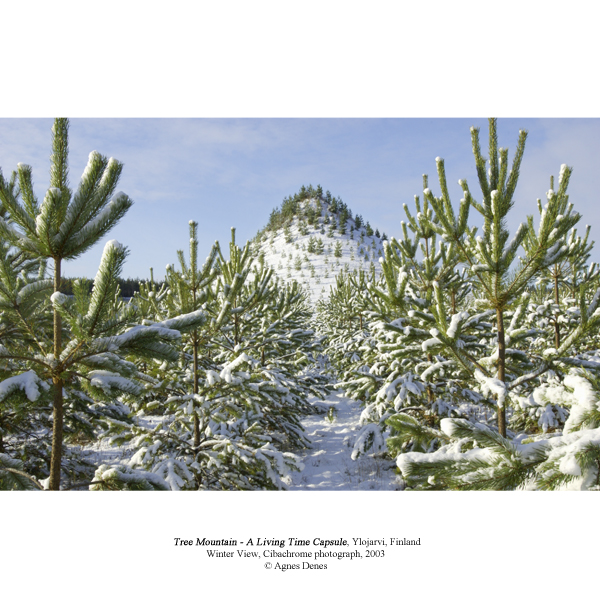

Dealing with living material is different in each situation. It’s life. It’s different in Living Pyramid, as it is in Wheatfield. They recreated my wheat field in Milan last summer, and it’s different in that situation. They want to recreate my huge reclamation site Tree Mountain in Finland. They say every country should have one, because it creates virgin forests.

I think long-term. I told you: I need 500 years. It takes 400 years to create a virgin forest, if you do it right.

Like the forest I want to do in New York: I want the people to plant the trees. I want people to come, New Yorkers and people from all over the world, to experience the trees. I want people to understand. The way I look at trees, to me they are just people without legs. Well, the roots—they have legs. Better legs than we do. Don’t let me get started on roots.

No eyes, either.

[Laughs] But look at the giant sequoias! Magnificent. They’re the most magnificent things on earth.

And as old as Western civilization.

It’s all of that, all of those dimensions.

You’ve mentioned that these are highly social projects that require the effort of many other people. How do you think about collaboration?

I love to work alone and I love to collaborate. Meaningful collaboration, when people come together and do something meaningful for other people and for the world, is very satisfying. It’s not just saying “I want world peace” or “I hate politics.” It’s not any of that—it’s just really, truly coming together. Not even likeminded people—you don’t even need that. You need people who believe in different things to come together and create something wonderful for the world.

I love humanity and feel so sorry for it. It’s a losing battle. So let’s make the most of it. Let’s do the most brilliant things we can do. Let’s be proud of each other.