For over a century, the Christopher Street Pier on the Hudson River in Greenwich Village, Manhattan has been a hub for the LGBTQ community. By World War I, the area was bustling with bars filled with transient seaman and Navy personnel, and due in part to an elevated highway (now demolished) that isolated it from the rest of Manhattan, it became an epicenter for flourishing gay nightlife. By the mid-1960s, the area was mostly abandoned as the maritime industry became nearly obsolete, yet the area continued to be a relatively safe space for men to meet other men. Following the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, the Christopher Street Peir was an important mainstay in New York's increasingly public gay culture; members of the community frequented the area for sunbathing and cruising, and gay bars took up shop in some of the formerly abandoned storefronts. According to the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, "The ground floor of the former Keller Hotel (Barrow and West Streets) housed the Keller Bar, which was reputed to be the oldest gay “leather bar” in the city from 1956 to 1998. The former American Seamen’s Friend Society Sailors’ Home and Institute (now The Jane hotel), subsequently became a transient hotel and theater venue; Hedwig and the Angry Inch had its Off-Broadway premiere here in 1998."

The terminals of the pier, dilapidated and unused, became sites for artistic intervention. Artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, Vito Acconci, David Wojnarowicz, and Peter Hujar photographed the scene and created site-specific works and performances. After the AIDS epidemic had reeked havoc on the gay community, and when developers began making plans for waterfront real estate renewal, the area became home to New York's highest concentration of homeless LGBTQ youth, many of whom were people of color, and had been pushed out by their families. (The 1990 film Paris is Burning documents the LGBTQ youth community in this area during that time.)

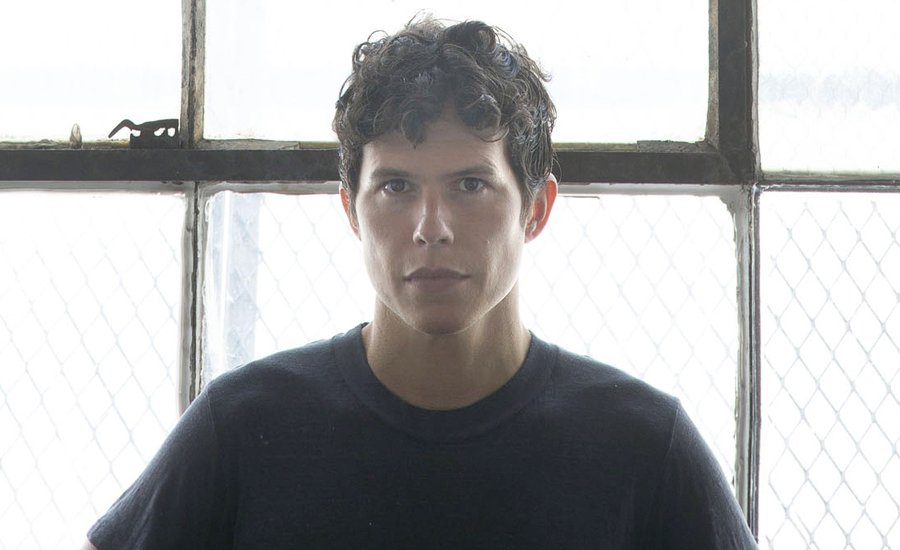

Now in 2018, the Hudson River Park—boasting bike paths, green space, dog parks, even trapeze—is enjoyed by New Yorkers at large, with little physical evidence of the significance the area has had within the queer community of New York. That is, until this weekend, when the city unveils a public artwork by Anthony Goicolea—the first official monument to the LGBTQ community commissioned by the State of New York. (The commission was formed in 2016 by Governor Cuomo after the tragic attack at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando that left 49 people dead.) Goicolea, a mid-career artist who lives with his husband in Brooklyn, uses a variety of media in his practice—including photography, sculpture, and installation—but working on a civic project of this scale is a first. Here, Artspace talks with Goicolea about what we can expect to see, his vision for the project, and how the Christopher Street Pier influenced him as a young gay man—and informed his approach to the monument.

Can you describe what we'll see when we visit the monument?

It's located between West 12th Street and Bethune Street in Hudson River Park, between the bike path and the esplanade (there's a grassy area there). When you enter into that area, there's a series of large stones—about nine of them total—that are arranged in a kind of circular formation. It envelopes you as you approach it and almost feels a bit like a harbor or a port. Part of the idea is to create this safe space in this environment that's reflective of the community. The boulders look as though they were made of granite but as you approach them, it's evident that they're actually bronze. One of the ideas behind the memorial is that it's constantly changing and evolving, revealing itself as you spend time with it. Initially it looks like stone and then you realize it's bronze.

Six of them are split and the void is filled with glass—the idea that this fracture has been mended with something that's traditionally thought of as being very fragile creates this super strong bond and unifies these rocks in a way that symbolizes the unification of the community. There are six of them because there are six bands of color within the LGBTQ flag. The glass provides a unifying element and follows the same contours as the bronze boulders and has these fractured angles that reflect and separate the light into different colors. The largest of the stones that's at the apex of this circular formation is also split, but where the others have glass, it has what appears to be nothing. As you get closer, you realize there's an inward-facing inscription. It's a quote from Audre Lorde that summarizes the intent of the memorial and speaks to the idea of how communities need to embrace their differences and how those differences are what make us stronger. The left-facing stone reads, "Without community there is no liberation...but community must not mean a shedding of our differences," while the right-facing stone reads, "Difference is that raw and powerful connection from which our personal power is forged." It's something that's revealed to you once you're fully ensconced in the memorial.

What's interesting to me is that these objects have been broken, literally ripped apart and split in two. And yet they unite again in a way that is more beautiful than they were originally. Holding them together are the conditions for a rainbow—accepting ambient light into their cores, and then projecting out into the world a rainbow of color. They're not unlike the community they represent.

It's interesting, someone was telling me that in ceramics, if something breaks, there's a process in which you use gold leaf to bond the ceramics back together. In using that gold leaf, it creates a bond that's actually stronger than what it originally was when it was whole. It takes on that property of mending something to create an even stronger bond.

They are also proportioned in this way that invites visitors to sit on them or climb on them. The fact that they're arranged in this circular formation, if more than one person is there and interacting with them, you're facing each other. It invites this notion of community and engagement.

Are they bronze coated or are they cast?

They're cast. I worked with a foundry Upstate, went to a quarry and selected rocks, scanned them, and then worked digitally to reshape the rocks to make them more specific to what I needed. From that, we printed a digital 3D print and used that to create a mold and cast from that.

Your work typically spans a lot of different media. Have you used these kinds of materials before or is this a departure for you? If so, what inspired you to develop this kind of proposal?

I haven't worked in bronze but I've used glass before. The studio I work with for that is based in Boston and I've used them in the past to cast cinderblocks made out of crystal and made this partition wall out of it. I've worked with large resin-based stones but not actual stones. This is the first time that I'm using bronze in place of stone and combining it with glass. It's also the first time I've worked on a permanent piece. Most of what I've done that's outdoors has been temporary.

The site of this monument is at the Hudson River Park, which used to be the Christopher Street Piers. What does it mean to you to produce a LGBTQ memorial in a place that has such a long and meaningful history within the community?

When I initially saw the open call for proposals, I was really familiar with where they were proposing to put the memorial for multiple reasons. When I first moved to New York, the Christopher Street Piers were still intact and it was one of my first interactions with the LGBTQ community in New York. I was raised in 1970s Georgia and so seeing that kind of comfort level and my community reflected back out at me—the fact that they didn't seem to feel vulnerable—was really invigorating. Knowing that the site was in such close proximity to that was one of those full circle moments.

I also used to run along the river all the time and just felt that it was a place I passed often and if I didn't at least apply or put something forth, I would always regret having not at least tried. That was definitely a part of the impetus in applying but then in thinking about it, it seemed that whatever was proposed should be somewhat natural and honor the fact that it's one of the few green spaces available to people, particularly on the West side. I wanted something that fit in with that and allowed people to still use the area. It's oriented in a way that it faces out towards the piers and out towards the Statue of Liberty. It's one of those things where I felt a connection with the site and if I didn't propose something, I'd most likely be unhappy with whatever ended up there.

Do you have anything else in the works?

I'm working with the LGBTQ Center to do an event on July 17th. It'll be a kind of 92nd street Y-style panel discussion between Ian Altava from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Assistant Curator for the Contemporary collection) and I about the memorial and the center and the LGBTQ community.

I can't wait to check it out and see it in person!

They feel great to sit on and climb on too—it's a nice moment. I'm really happy with how they turned out.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Why Does the New York City AIDS Memorial Matter? Read Testimonials From Leading Cultural Figures

[related-works-module]