In this special feature for Artspace , the Brazilian-born, Brooklyn-based sculptor Gustavo Prado gives us a step-by-step inside account of how his recent commission Daphne’s Eyes came to fruition, from concept to completion. Click here to learn more about Prado and his work.

My invitation to install a new work at the Drake Hotel Devonshire—located in Prince Edward's County outside of Toronto and known across Canada as a hub for contemporary art—came after its curator Mia Nielsen saw two of my sculptures at the Spring Break Art Show this past March. There, I showed a wall piece called I Gazed a Gazeless Stare and a larger standing piece called Watchtower in a room curated by Marc Azoulay.

I Gazed a Gazeless Stare (Measure of Dispersion Series)

, 2015, available on Artspace

I Gazed a Gazeless Stare (Measure of Dispersion Series)

, 2015, available on Artspace

When Mia's right hand woman Ashley Mulvihil first contacted me, the invitation was to install a work in the new park that had been incorporated into the Drake Devonshire Hotel’s gardens. However, as soon as I saw the first pictures from Toronto, I set my sites on a different location: a tree that stands between the hotel's house and a beautiful beach facing Lake Ontario.

The tree’s branches appeared to be pointing to the horizon, and in a way, seemed to be a connector between that vast space and people standing at different heights from the balcony to the beach. The tree stands directly under the trajectory of the sun as it makes its arc from sunrise to sunset, a lucky happenstance that would dramatically transform the experience of the work throughout the day. Last but not least, the changing of the seasons means that the colors on the surface of the artwork would shift radically over the course of the year.

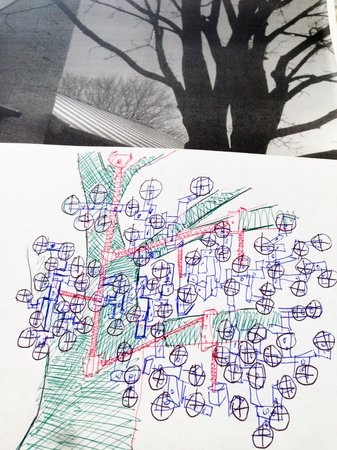

In order to seize the opportunity to do a piece that could unite so many different kinds of movement, I had to get what, in my mind, was the prime real estate of that tree. Although Mia and Ashley were open to it, time was running out; they had decided to include me in that season's programming "late in the game," as they put it. They challenged me to come up with simulations and drawings to show them what the piece could look like. These had to be completed in just two days, or we would have to stay with the park option.

There was an additional challenge—in installing the piece, I couldn't do anything that might harm the tree. That meant no drilling of any kind, which would have been the simplest, safest way to go for a heavy sculpture with people walking and sitting under it.

In order to protect the tree, the first simulations had several half-inch rods coming from the steps in the stand right under it. These acted like columns, elevating most of the structurethat would carry the mirrorscloser to the branches. That option was approved and I flew to Toronto a few weeks later, not completely satisfied with it but secretly confident that I could come up with something better onsite.

On arrival, while talking to Ashley and Damian Cohen—who assisted with the installation there—I decided to change the work completely. Instead of creating columns for support, we would hang the structure from a few of the tree’s higher branches and use lower ones to lock the whole piece in position to keep it from shaking. The added advantage to this approach was that it would place most of the mirrors at eye level for those standing at the balcony and help guide their gazes towards the horizon, creating a vanishing point of sorts.

In order to avoid drilling, I used perforated steel straps, and, with Damian's assistance, was able to encircle the branches. Once the rods sustaining the piece were connected to those straps and the basic structure was set up, all that was left to do was finish painting the rest of the parts and prepare the mirrors.

That process took place in an old factory warehouse on the side of a road, in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by different kinds of crops and fields. I worked there alone for hours, until this huge tractor with large wings that sprayed pulverizer started slowly moving in the field towards me.

Back at the hotel, we put up a big table with all the parts needed to complete the work. With Ashley’s assistance I began to add new sections and corresponding mirrors, walking down the ladder to check what they were capturing and from where they could be seen. The challenge was that with the temperature in the lower 30s and winds coming from the lake that plunging it even lower, I had to work all sealed up under my coat.

The piece was finally finished a few weeks later, after my conversation with my friend Ricardo Kugelmas during one of his visits to my studio in Harlem. We were talking about one of my sculptures called Narcissus when I started showing him the pictures from Toronto.

Narcissus (Measure of Dispersion Series)

, 2015, available on Artspace

Narcissus (Measure of Dispersion Series)

, 2015, available on Artspace

The moment he saw the installation embracing the tree, he enthusiastically pulled up his phone to show me another piece of art that, in his opinion, had a strong connection to it. I’ve seen him do this many times, of course, but I couldn’t have expected him to show me Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne.

We started discussing not only how it is one of the best sculptures ever made but, the myth behind it, how Daphne turns into the tree after being touched by Apollo. Like Bernini’s sculpture, the Toronto piece attempts to encapsulate perpetual movement while also playing with the ancient myth by bringing together the sun and the tree. Ricardo was very insistent that I reference the older work in the title of my piece, saying that it would be a good addition to my other pieces Narcissus and Icarus .

And so I did. The title Daphne’s Eyes made sense to me—her eyes are really the link connecting all aspects of that instant: Apollo closing in, after a long chase, finally reaching and touching her skin, and the horror of watching her fingers turning into branches and leaves.

Winter

Spring

Summer

To see more works by Gustavo Prado, check out his artist page here .