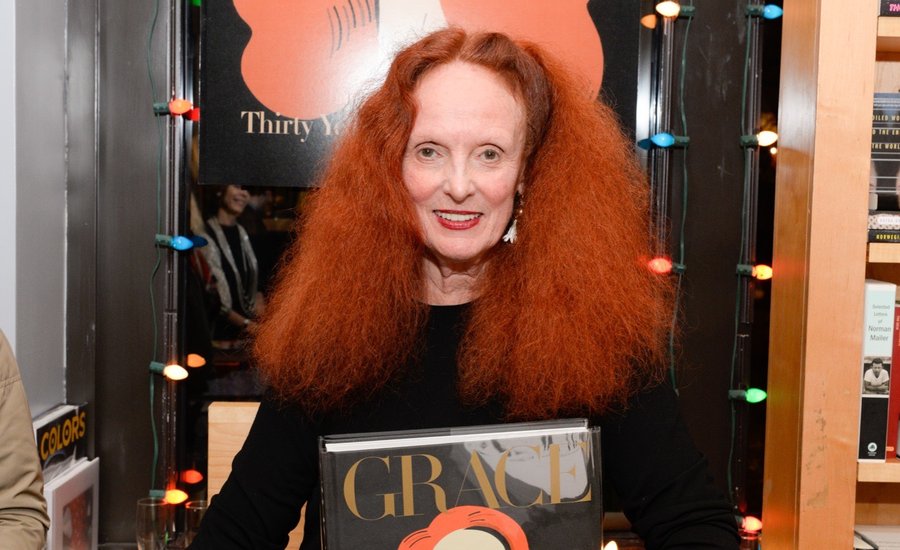

As the longtime and much-adored creative director of U.S. Vogue , Grace Coddington is a central figure—some might say the central figure—in defining the idiom of contemporary fashion photography as an art form unto itself. Her singular vision, developed in part while poring over outdated issues of Vogue during her childhood on a windswept Welsh isle and refined over her years of work in the industry both in front of and behind the camera, has won her the kind of recognition few fashion insiders can hope to achieve.

Now, she’s following up on the success of her 2002 Phaidon compendium Grace: Thirty Years of Fashion at Vogue with Grace: The American Vogue Years, covering her work in the U.S. over the past 15 years. In honor of today’s release of new book and in celebration of New York Fashion Week (also opening today), we’re excerpting part of former Vanity Fair fashion director Michael Roberts’s introductory essay, which focuses on how Coddington is adapting (or not) to fashion’s newly networked online ecosystem.

To read the whole essay and see all of Coddington’s favorite shoots of the new millennium, purchase the book here .

All in-demand stylists of fashion images have their own look, from hard and sexy to minimalist and waifish. Connoisseurs of fashion pages can tell a Grace Coddington shoot by its poetic underlay, often with a motif of arrested innocence, and a prevalence of fellow redheads. The models frequently find themselves traversing otherworldly surroundings dressed in unlikely but not entirely inappropriate outfits. Others are marooned without makeup or hairbrush in the kind of broody landscape that recalls Anglesey, the inhospitably damp and misty island of Grace’s childhood. Families, too, play a surprisingly large role in her fashion pictorials, with gurgling infants chasing around the pages, perhaps to compensate for Grace’s own domestic life, which fractured early in her career. Finally, there are those intricately embroidered European fairy tales and moments of pure English whimsy that she has managed to retain as part of her fashion lexicon despite relocating to practical American shores more than three decades ago.

Today, Grace’s type of genteel Americana is an immutable part of the magazine she serves, whether it’s a Douglas Sirk–style suburban couple with marital problems, dressed in swoonworthy 1950s fashions, or a roughneck cowboy and his girl posing in a barn. But whatever the scenario or narrative, the focal point is always the clothes. “If you do not show the clothes, it is not a fashion photograph,” she says firmly. As a designer once told me, “Grace always picks the key outfit in any collection. It is never the obvious one, or the most popular. But it’s the one that sums up what we have just seen and the one we remember. Which is what makes her such a great fashion editor.”

As for her approach: “Conceptual?” she harrumphs. “That’s a big yawn to me. Fashion is not simply about seeming cool. At this moment I think a fashion story looks better if it’s believable. And what is considered new right now is to look very ‘undone,’ which you almost have to do and then ‘undo.’ Not, of course, to be confused with just not doing anything.”

Digital photography, she knows, has its advantages, “But I think real film is so much more magical. Nothing can replace the anticipation of waiting for actual photographs to come in. On the other hand, digital does give you a certain comfort in knowing the picture is actually there, not to mention the pure convenience of being able to alter things on the spot.”

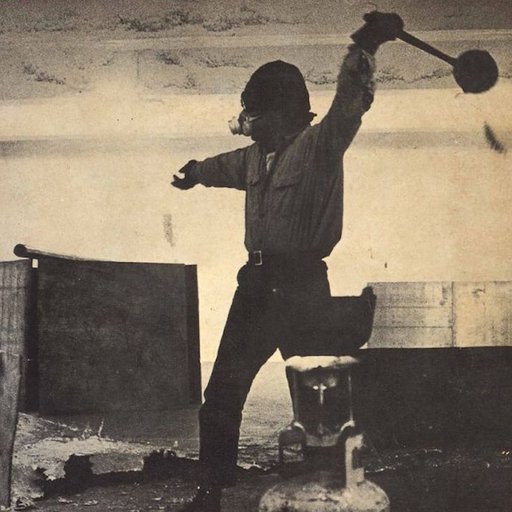

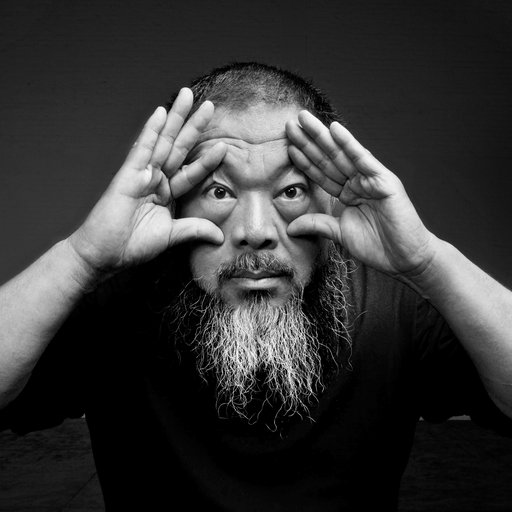

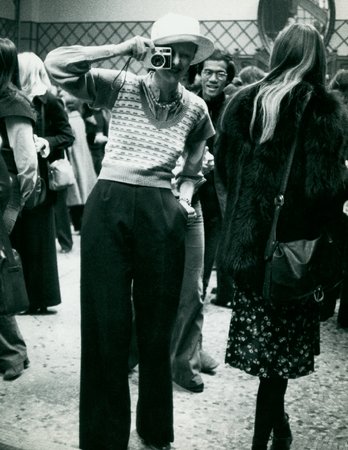

Coddington caught in a candid moment by Bill Cunningham in the 1970s

Coddington caught in a candid moment by Bill Cunningham in the 1970s

While working on Grace’s last opus, a brilliantly written memoir, I was invited to stay for a few days at her unassuming house in the Hamptons. Hailing as I do from the English countryside, I must confess to feeling underwhelmed by that well-heeled suburb’s manicured greenery, not just because of its clipped artificiality but because it seems to be peopled by oh-so-many fashionistas from the East Coast and beyond.

Yet Grace, who has become practiced over the years in hermetically sealing herself off from any circumstance, thrives outside the city limits, and her weekend home in its abundantly leafy setting is an enchantingly atmospheric hideaway. It also supplies the occasional backdrop for those modest Vogue shoots that crop up during the August vacation, sessions showcasing the newer models that don’t require lavish productions in faraway places.

In the house, each spatially challenged wall bristles with Grace’s drawings of her beloved cats, or with vintage photographs by masters of the craft. Shelves and closets hold more of these, still encased in the Bubble Wrap they arrived in when she first acquired them.

“It didn’t occur to me until quite late to collect old photographs,” she says. “Whenever I used to go antique hunting in Paris, I was more concerned with the fabric on an old sofa than with things to hang on the wall. But in the mid-seventies, when they closed Vogue Studios in the British Vogue building, word got around that if you hurried, you could salvage old photos from the garbage bins. I managed to save a vintage Cecil Beaton—and that was really the start of my collecting.”

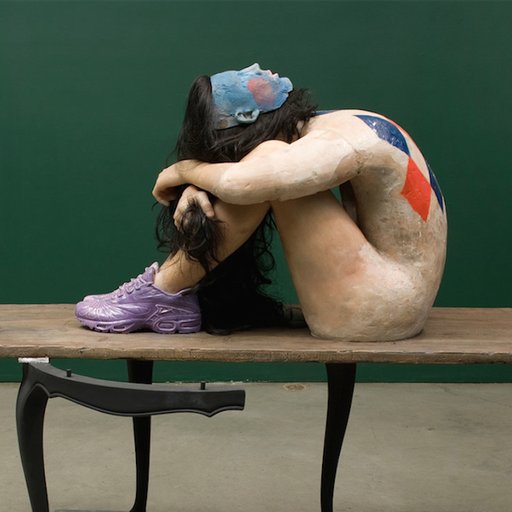

Karen Elson (in the style of Grace Coddington), photographed by Steven Meisel in 2008

Karen Elson (in the style of Grace Coddington), photographed by Steven Meisel in 2008

In these digital boom times, far from the Beaton era, breakthroughs in modern technology tend not to have Grace executing high kicks or twirling pom-poms over each new gadget, even if she does boast around 150,000 followers on Instagram [ the number is now over 260,000—Artspace editors ]. After all, she didn’t possess a cell phone until 2006, and until recently the desktop computer in her Manhattan office stayed mainly unused.

“I don’t regularly post anything,” she says. “Well, maybe once a month—perhaps a drawing of my cat. And I don’t write things like, ‘This is what I’m having for dinner,’ either—and then post a picture of a tomato salad.”

A lot of her vitriol is expended on selfies. “Why would you want to take a photograph of yourself every five minutes?” she wonders. “And in such a way that makes you look ugly because they are usually taken from a level below your chin, which is so unflattering?”

When riled by any of these intrusive examples of our rapidly changing world, Grace’s voice takes on the curt, dismayed tones of a games mistress at a prestigious prep school that has seen better days. This also applies to phenomena such as street photographers, whose charms are particularly lost on her. “They take pictures of anybody and everything. It’s so indiscriminate.”

One exception, oddly enough, is the social-media-type girls like Gigi Hadid, Kendall Jenner, Cara Delevingne, and Taylor Swift. She appreciates their role in today’s culture and their spirit of fun—although my feeling is when that fun runs out, one might easily find her using a selfie stick as a cattle prod, rounding them up and herding them into a soundproof changing room before bolting the door and throwing away the key.

Blogging, tweeting, and live-streaming have made it pretty near impossible to imagine a rosy future for Grace’s world of glossy magazines, with their old-time conceits of high-fashion models tumbling down rabbit holes, sipping tea with robots, or dressing up as princesses and punks. Well, tempus fugit, as they say. And nothing flies faster from its moment than a fashion trend.

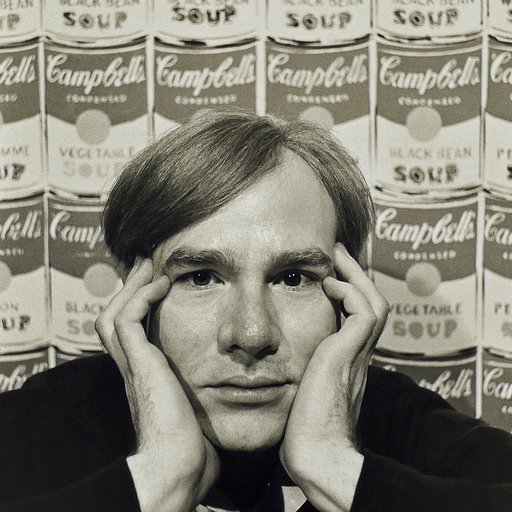

Coddington's distinctive mane, photographed by Anton Corbijn in 2014

Coddington's distinctive mane, photographed by Anton Corbijn in 2014

Recently I tentatively asked Grace what crosses her mind when she hears the word modern? “I’m probably not considered modern,” she responded crisply. “In fact, not being modern is something that is thrown at me all the time. Yet there are some days when I think I have a fresher mind than those who are considered modern. To me its true meaning is always to be one step ahead. A feeling of rightness. Although when a thing is called modern it’s already old-fashioned!” she added.

Grace, too, has changed over the past decade and a half from being a fashion insider to finding herself a highly public person. Her appearance in the widely seen 2009 fashion documentary The September Issue has greatly affected her life and colored the way she views herself. The Grace of fifty years ago was a shy and retiring neophyte editor, a fashion-conscious introvert who dyed her hair yet grew it in secret under her turban for an entire year.

The Grace of today is a far more self-assured, forthright creature. Recognized as an influential septuagenarian of style (one who now even comes equipped with an eponymous perfume), she offers her direct opinions from under a blazing carrot-colored thatch that can be easily spotted the length of Yankee Stadium.

“I’ve given myself something of a contradiction. It makes me instantly identifiable and yet I crave anonymity,” she says with a smile. “So I guess, in a way, I’m lying to myself.”