As I watched the Cuban immigration agents across the table rifle through my belongings and view each of the the folders and photos on the eight flash drives I had brought with me as gifts (computer supplies are in short supply in Cuba), I realized it might not have been the best decision to (a) bring so many flash drives with me, and (b) travel using two different passports (U.S. and Italian) on consecutive trips to the country.

In the brightly lit side room at Antonio Maceo Airport in Santiago de Cuba, the line of questioning went something like this:

AGENTS: “Are you American or Italian? And why two trips within a month?”

ME: “I’m an artist working on a project photographing endemic plants in Cuba.”

AGENTS: “So you’re a photographer, not an artist?”

ME: “I’m an artist taking photographs of plant species at Humboldt National Forest”

AGENTS: “Ah, so you’re a botanist! How many endemic plant species are there in Cuba?”

ME: “The exact number? I’m not sure, but there are quite a few.”

AGENTS: “How come you wouldn’t know the exact number if you’re a botanist?”

This grilling went on for about an hour, during which time several immigration officials cycled through the room, examined files on my drives one by one, looked me up and down, and left. Finally, I was allowed to enter the country.

The objective of the trip was to travel to Humboldt Forest to photograph endemic plant species for my most recent series, “Natural Abstractions,” inspired by the nature motifs in 19th-century Japanese prints that in turn influenced the European Impressionists. The series is a collection of gilded prints and is available exclusively on Artspace.

I also had a new assignment from Artspace’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein: document the trip and come back with an art travelogue that reveals something about the current artistic scene in Cuba. So I returned to Cuba for a two week trip, this time with the documentary filmmaker David Kennedy, spending time in the rugged and less traveled eastern part of Cuba—Santiago and Guantanamo provinces—before taking a 17-hour bus ride across the country to visit Havana and check out the art scene there.

A sign of thawing Cuban-U.S. relations

A sign of thawing Cuban-U.S. relations

Coincidentally, we arrived during the most important week in Cuban-American relations since the revolution. Obama began his visit three days before we touched down, the Rolling Stones played in Havana the night we arrived, and the talk everywhere was about change. The people we met were guardedly optimistic about their futures and universally open and friendly towards Americans. Almost everyone had family members in the U.S., and many dreamt of moving there. “Me encanta America” is a phrase we heard often.

I had been to Cuba the month before, when I spent two weeks alone traveling back and forth across the length of the country (47 hours of bus travel in 14 days) with the goal of shooting in Humboldt. Unfortunately, when I finally arrived in Baracoa on the previous trip the weather was nonstop rain, with another week of heavy weather projected, and I was not able to make it to the forest because of the conditions on the rutted and partially unpaved roads.

Determined to finish the project, I went back to New York and planned another trip. This time luck shined on me. Accompanied by Kennedy, my filmmaker friend whose last name elicited surprise and good-natured jokes at the ticket counters everywhere we stop, we arrived in Baracoa after a seven-hour bus ride from Santiago, crossing the mountains and arid plains of Guantanamo province.

Baracoa, Cuba is about as far from Havana as you can get in the country, both geographically and culturally. Located on the north coast at the far eastern corner of the island and only accessible by boat for almost 400 years, it is Cuba’s oldest and most culturally unique town. It’s surrounded by high mountains and abuts both the driest and the wettest areas of the country; there are arid semi-desert plains to the east, and to the west sits the Humboldt national reserve, the largest rain forest in the Caribbean.

We attempted to stay outside of Humboldt forest in the small beachside village of Maguana, but it was too difficult to arrange the logistics of the daily transport to the rain forest (we weren’t able to find a driver in the village with a car sturdy enough to make the trip—they were all afraid of breaking an axle). We turned back and decided to make Baracoa our home base and hire a car daily to take the one-and-a-half hour trip past the cacao and coco farms along the rutted and partially unpaved roads.

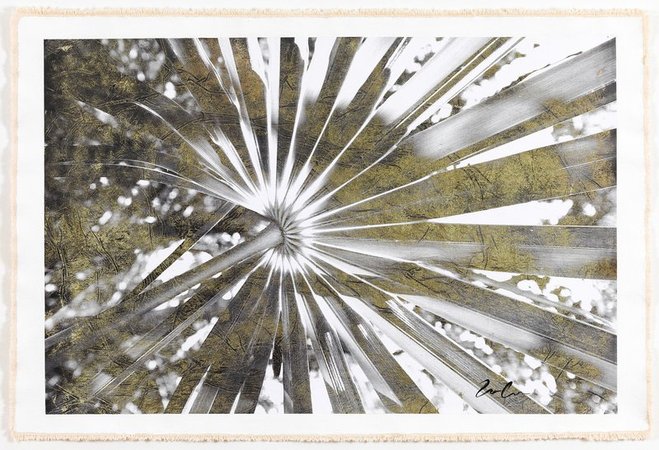

Bill Claps Forest Palm, 2016

Bill Claps Forest Palm, 2016

Fortunately, we connected with Enrique, the proud owner of a fire engine red ’57 Ford. Its long and wide chassis base and loose suspension were ideal for gliding over the huge potholes in the road, and we sat back took in the ride, floating in its red and black cushioned seats that felt like a saggy mattress with loose bedsprings.

Humboldt is the largest rain forest in the Caribbean and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. 90% of its plant species are endemic (found only in this rain forest), a highly unusual scenario resulting from a combination of the ecosystem’s isolation on an island peninsula surrounded by semi-arid land and the exceptionally acidic underlying rocks, which gives rise to highly adaptive plants that don’t live in other soil conditions.

Humboldt is also an important bird and animal sanctuary, home to many rare tropical birds including the Zunzuncito, the world’s smallest bird. New plant and animal species are regularly identified in the park by research teams from Germany, Canada, and the U.S, with many species still undiscovered.

Our guide Javier is a former employee of the logging company that previously held the logging concession in the park. Patient and methodical, he identifies over 50 endemic species as we hike through the rain forest. Fueled by cucurucho, a concoction of coconut, guava, honey, and papaya served in a palm frond cones, we moved through the forest photographing and documenting the species.

One of my favorites was Cocotrina Halesander, named after the eponymous Alexander Humboldt, the naturalist-explorer who first came here in 1801. An endemic palm tree with circular fronds, it punctuates the forest with translucent geometric patterns. Of course, there’s also Lengua de Vaca, a plant commonly known as Raspa Coolo (ass scraper), whose underside is used in lieu of toilet paper by the locals. We were fortunate enough to see many rare birds and even spotted a Cuba Libre, a hummingbird sized bird with a beautiful translucent blue body. The wealth of photos I collected were more than enough to provide source materials for the project I had undertaken for Artspace.

Bill ClapsCocotrina Halesander, 2016

Bill ClapsCocotrina Halesander, 2016

Back in Baracoa we relaxed in the bars and music venues in the town, which is the birthplace of Kariba, the forefather of Son, the popular Cuban music form. Baracoan cuisine is famous as the most eclectic in Cuba, a country known for its monotonous fare of pork, chicken, rice, and beans (a running joke is that if you want good Cuban food you need to go to Miami). In contrast, Baracoans use spices, fruits, and coconut to enhance their dishes; our favorite was fish with lechita sauce, made of coconut milk, tomato sauce, garlic, and spices.

Throughout the trip we stayed in “casas particulares,” Cuban homes where the owners rent out a room or two to travelers. It’s the best way to experience Cuban life, where you can receive some local wisdom and tips on how to get around and navigate the system like a Cuban—a helpful skill in this two-currency economy. The houses are typically very simple but clean and often decorated with plastic flowers and kitchy décor that reminds me of the ‘70s Miami interiors of the film Scarface. Maricela, the owner of our casa in Baracoa, was always quick with a laugh, playfully poking fun at our American habits, while providing us with us a lot of valuable practical information.

We eventually made our way back to Santiago, the most Caribbean and African of Cuba’s cities, with its constant bustle, colorful street life, and music everywhere—on the streets, emanating from homes, in cafes and dance clubs.

The constant barrage of approaches from “jineteros,” (literally “jockeys,” an appropriate term for the hustlers who try to “ride” tourists for profit) can be somewhat unnerving on the streets and in the public squares and night spots. As a man you are constantly approached by women asking you if you want company, and by men who try to steer you to a restaurant or a bar, where they receive a cut of what you spend. With the average Cuban salary at around $16/week, their cut of your two $1 beers could be the equivalent of a day’s salary, hence the constant hustling.

The question on every foreigner’s mind is: how do Cubans survive? Housing, education, and healthcare (amongst the best in the world) are all free, and every person receives a monthly food ration that includes staple items including a ration of rice, beans, milk, sugar, potatoes, eggs, and some meat. The ration is a constant source of dark jokes amongst the Cubans, as it barely gets them through half the month. Everyone has to figure out how to supplement their income in order to survive day to day, which might mean “borrowing” cigars from the factory you work in to sell to tourists, filling used plastic bottles with the local draft Hatuey beer bought at the factory to sell by the cup (for five cents) at makeshift music venues or on the street, or hustling tourists in one form or another.

After a sixteen-hour bus ride across the country (domestic plane tickets are typically unavailable unless reserved far in advance) we finally arrived in Havana to check out the art scene and meet local curators and artists.

For a country so rich in international artists working on the international scene, it’s surprising that Cuba has no official contemporary art museum. In its absence, the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam has sometimes served that function. Located in a colonial style building next to the cathedral in Old Havana, supported by the Cuban ministry of culture, it is a center that showcases local and international art and serves as the nexus for the Havana Biennale, which takes place roughly every three years depending on government budget and political will.

We were fortunate enough to connect with the Lam Center founder and curator Nelson Herrera Ysla, whose exhibition “La Madre de Todas las Artes” (The Mother of All Arts) showcased Cuban artist’s perspectives on and appropriation of Cuban architecture. With many of the buildings in the country in the process of decay, Cuban architecture serves as an inspiration and starting point for many Cuban artists.

I was able to speak with several artists included in the show, whose perspectives involved using humor, nostalgia, irony, and metaphor to propose new interpretations of their architectural heritage. Photography, installation, painting, and video were all represented. Alex Hernandez’s drawings and paintings compare the lifestyles and expectations of Cubans in different social systems by showing the similarities and relations between houses owned by the same people in Havana and Miami. Eduardo Ruben, trained as an architect, creates artworks that forge a link between painting and photography. In Arianma Contino’s black constructed paintings, an oil platform punctuates an otherwise undisturbed horizon. In a country where the seascapes are typically linear, pristine, and strangely unpunctuated by boats (Cubans aren’t allowed to have them, for fear they’d flee the country) the platform breaks the plane and begs questions about development and progress.

Cuban daily life is a major inspiration for many Cuban artists. The proximity of generations of people living closely together under the same roof, the every day struggles, the sounds of the streets, and the music all provide such a rich context in which to produce art. The daily struggle to procure the basic materials of everyday life effects artists strongly; in a country where art supplies are in very short supply, artists are forced to be extremely resourceful, often using found materials in their work.

Many of the artists we met maintain homes and studios in Vedado, the commercial hub and heart and soul of the city, including Abel Barroso, an artist we visited who has shown widely internationally. Originally trained as a printer, he now uses carved printing woodblocks as the basis for his three dimensional sculptural objects and installations, which take the form of objects as varied as board games and pinball machines. His work comments on the cultural and interpersonal consequences of living in relative isolation on a sequestered island nation, and the objects weigh heavily with political and cultural commentary, often referring to Cuba’s isolated position in a globalized world economy.

Much of the work we saw in Cuba, while not always overtly political, has as least some political overtones and social commentary. But none of the artists I spoke to, understandably, would admit to any form of political commentary. When I pressed, most said their work was “social”—not political—commentary, but I soon stopped pushing the issue out of respect for their vulnerable positions.

Vedado is also home to Fabrica de Arte, an art and music exhibition and performance center located in an abandoned oil factory. In an unusual partnership between the Ministry of Culture and private operators, the government leased the building to local musiciana to develop a space for Cuban artists to showcase their work in an environment more accessible to the young public. The venue hosts several areas for music and various exhibition spaces. It’s been a huge success, filled four nights a week with Cubans and foreigners alike, who are entertained by top musicians from around the world.

As you wander through the side streets of Vedado, by the decaying mansions and stately buildings that used to house embassies and thriving businesses, you can imagine the glamour and luxury of Havana’s heyday, when Meyer Lansky and his boys from New York had the whole place rigged, with the compliancy of the C.I.A. and the U.S. government, paying off Battista and his cronies with a percentage of the take, and exploiting the country like their own private fiefdom. It all worked smoothly as long as the Cuban people were kept in check, but we all know how the rest of the story went: Castro’s underdog story, then Che’s lightning strike across the country to rout Batista’s forces in the western provinces and Havana, driving industrialists, American imperialist interests, and the Mafia from the country for the next fifty plus years.

A typical car in Cuba

A typical car in Cuba

But the Americans are coming back now, and will soon be returning in droves if the current trajectory continues. American companies and private-equity groups are already positioning themselves to cut deals with the Cuban government. And lots of foreigners are “buying” homes and apartments, usually in the name of a local resident, to be rented out to tourists at high prices, or as property speculation.

It will be very interesting to see how this story plays out, if history will repeat itself, if Cuba again will be sold out piece by piece to the highest bidder (or briber). My personal feeing is that change will come quickly in the minds and attitudes of the people, but it will take a very long time for the country’s infrastructure to change visibly, as the entire country is in an almost total and extended state of disrepair. I imagine that the first wave of development will be tourist-related interests, but any potential consumer businesses targeted towards the local population base will have to wait until the Cuban people begin to earn first-world-standard wages and develop disposable income.

I don’t think there’s much of a risk of seeing Starbucks billboards and Chase Manhattan branches on every corner anytime soon, but it certainly could happen eventually. I feel fortunate to have experienced it all before the Donald Trumps of the world turn the country into a Cuban theme park, and the Humboldt rainforest (God forbid) into a golf resort with beachside condos.