In honor of the opening of the 2016 Rio Olympics , we’re excerpting this brief rundown of one of the most important art movements to sweep the Brazilian art world— Concrete Art , also known as Concretism . As this essay excerpted from Phaidon’s Art and Time shows, while the movement was started in Europe, it reached its full bloom only in the warmer climes of Latin America, where it lated mutated into what’s now called Neo-Concretism . Read on to find out more about this revolutionary movement.

Great Artworks Worthy of the Olympics featuring paul mccarthy, richard prince, jonas mekas, and more buy now

There are few twentieth-century art movements that flourished for more than forty years, inspired artists in at least a dozen countries, and even became the semi-official style in several cities in Latin America. Concrete art’s ambition was to synchronize abstract art with the rationalized values of a well-planned, modern society. Artists looked to forge links with industry and technology. They believed that art forms should be universally apprehensible, based not on personal intuition, but on pre-established rules. In practice, however, Concrete art demonstrates how difficult it is to isolate impersonal and reasoned ambitions from all other facets of human experience, including at times the capricious and irrational.

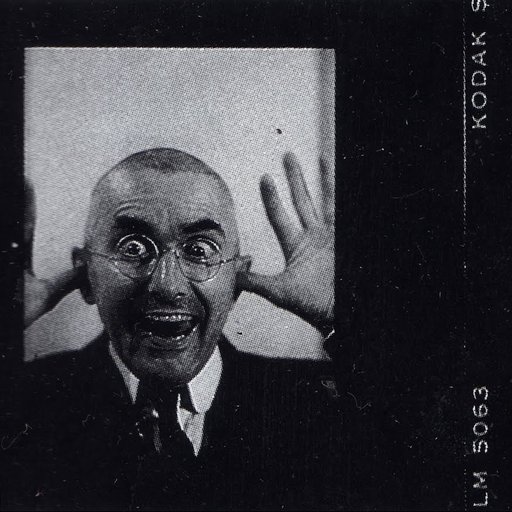

The term was first coined by the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931). In 1930 he founded the journal Art Concret , in which he advocated that painting should mean nothing but itself, because “nothing is more concrete, more real, than a line, a color, a plane.” This literalist premise underpins all Concrete art, and predates by more than thirty years the espousal of similar principles by the Minimalists .

AAT

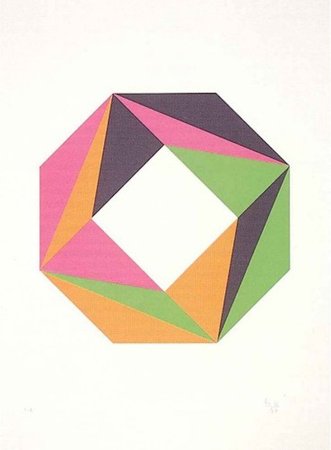

by Max Bill (available on Artspace)

AAT

by Max Bill (available on Artspace)

The values of Concrete art were later adopted by the Swiss artist

Max Bill

(1908– 94). His own work displays his admiration for mathematical lucidity, particularly with the topology of the Möbius strip, which he explored sculpturally in multiple materials and configurations. Bill wanted to produce objects that render abstract thought visible, yet he was equally fascinated with spatial deception and visual ambiguity.

Visible Idea

(1956) by Waldemar Cordeiro

Visible Idea

(1956) by Waldemar Cordeiro

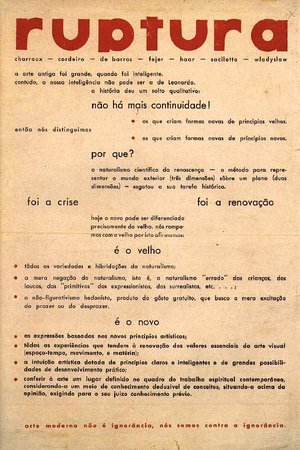

During the 1940s, Concrete art gained popularity in South America. It was first adopted by Argentinean and Uruguayan artists, who developed an alternative orientation for it by equating it with Marxist politics. In the 1950s, Bill’s work was exhibited in São Paulo, and the following year he won the grand prize at the city’s first Biennial. His work struck a chord with Brazilian artists, and several travelled back to Germany to study at the technical design school he had cofounded in Ulm. The Biennial also inspired seven São Paulo artists to form Grupo Ruptura, whose spokesperson was Waldemar Cordeiro (1925–73). Many of Cordiero’s paintings were titled

Visible Idea

, accentuating his rationalizing agenda.

The Grupo Ruptura manifesto, published in 1952

The Grupo Ruptura manifesto, published in 1952

In the 1950s, Eugen Gomringer (b. 1925) from Switzerland and Haroldo de Campos (1929–2003) in Brazil extended the term “Concrete” to refer to a new mode of poetry. Their aim was to condense poetic structure radically, exposing the optical and sonorous materiality of language. The result was a fusion of the visual and verbal that spread rapidly across the globe and provided an invaluable collaborative forum for visual artists and poets.

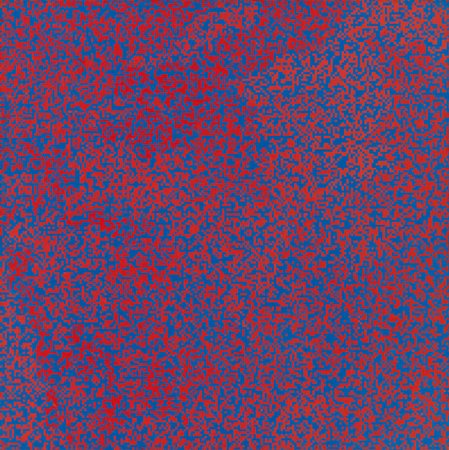

Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares Using the Odd and Even Numbers of a Telephone Directory

(1960) by François Morellet

Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares Using the Odd and Even Numbers of a Telephone Directory

(1960) by François Morellet

By the 1960s, artists were adopting procedures that exposed the inherent problems of a Concrete aesthetic. The French painter François Morellet (b. 1926) realized that any art composed by an individual necessarily involved personal choice, and so could not be universal. The only way to eliminate subjectivity was to adopt chance procedures. As a result, the ordered ideals of Concrete art had to be jettisoned, leading to a new chapter of impersonal, rule-based art outside the rationalizing premise of geometric abstraction .