Figuration in painting is hot again (at least for the time being), and galleries from New York to London are currently chockablock full of canvases depicting humanity’s favorite subject matter—ourselves. Luckily for fans of the painted form, Phaidon’s new Vitamin P3 —profiling 108 of the most important painters of our time —features no less than 56 artists from around the world working primarily with the figure. Here, we’ve excerpted essays on three of the most interesting (incidentally, all women), who use their medium to say something new about the human form in the digital era.

ELLA KRUGLYANSKAYA

Born 1978, Riga, Latvia. Lives and works in New York

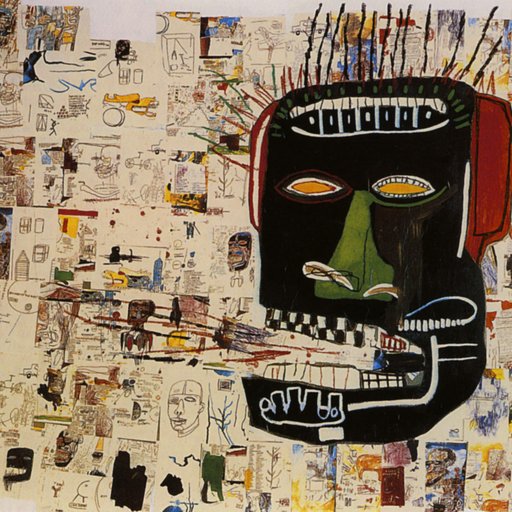

Negative Vibes

, 2013

Negative Vibes

, 2013

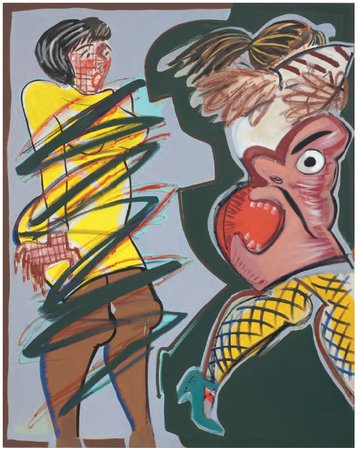

Ella Kruglyanskaya paints with big, bold strokes, capturing on her canvases big, bold female forms. Exaggeration seems to be a strategy for this Latvian-born painter. Her women are endowed with the fullest of features: bulbous breasts, hourglass waists, rounded thighs and muscular calves. Heavily colored and outlined, Kruglyanskaya’s women share some similarities with the French painter and sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle’s (1930–2002) exuberant and rotund Nanas (the first of which appeared in 1964), but also with Willem de Kooning’s (1904–97) grimacing gargoyles or, perhaps, Picasso’s fragmented, sensuous muses.

The color palette of Kruglyanskaya’s paintings is bright, matching the boldness of her subjects: she swathes her figures in lavenders, yellows, oranges, turquoises and reds, using pineapple patterns and vibrating checks. Many of her imagined garments, which hug the voluptuous forms of her women, seemingly possess personalities of their own, with faces—and grimaces—that double those of the wearer. Curvaceous and fierce of feature, Kruglyanskaya’s women often appear in pairs—and the pairing is hardly ever complimentary. Rather, these paintings are filled with animus, expressed through narrowed eyes and gaping mouths.

Lemons and Lips

, 2011

Lemons and Lips

, 2011

In Negative Vibes (2013), a female face is frozen in shock before a man with a pencil moustache, who appears outraged or abusive or both. It takes a second glance to notice that the man’s face in fact belongs to a woman’s dress, stretched around her mid-section. Using both shaped canvases and traditionally stretched ones, Kruglyanskaya imbues each painting with movement and fervor. Her scenes depict moments that are suspended yet full of agitation: her women seem to be constantly in motion, moving across or out of the picture plane. As such, they are anything but static: in the vibrancy of their colors, the swiftness of their lines and the angles of their eyes, these women communicate loudly or, as seen in Lemons and Lips (2011), pointedly.

Often caught in conflict with one another, Kruglyanskaya’s characters “act out,” shooting prideful glares and making silent, envious accusations. In some of her paintings, these resentments manifest as bold, black marks where characters seem to scribble out the other with a look or appear as yesterday’s news, used to wrap up fish ( Fish, Red Bikini , 2014). Kruglyanskaya’s paintings capture something of a modern feminine experience where the painting becomes, in the artist’s words, a “pictorial event.” Though the fashion choices she depicts may be more at home in the 1960s or 1980s than today, her comic book-inspired paintings plumb and generate contemporary commentaries about fashion, judgment, competition and gender constructions.

– Jens Hoffmann

MERNET LARSEN

Born 1940, Houghton, MI. Lives and works in New York and Tampa, FL.

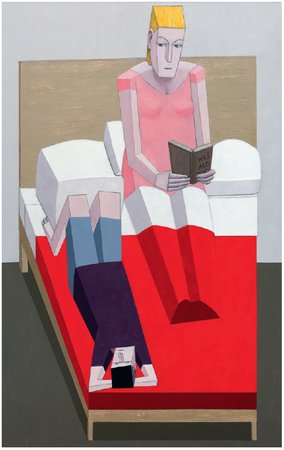

Reading in Bed

, 2015

Reading in Bed

, 2015

Since the late 1970s, Mernet Larsen has developed a highly original pictorial technique with the uncanny property of turning narrative figuration into still life. Her paintings stop time—they distort space, they reverse sequence, split perspective—all while standing still. Figures play out various scenarios, some as commonplace as stretching or sitting, others more akin to ritual or the surreal, such as Chainsawer and Bicyclist (2014). In each, a kind of delirious geometry seems to emerge, whereby the fantastic and the mundane become crystallized in the process of being rendered.

There is a certain anxiety in this figuration: the geometry can appear constricting or warped, and figures often face each other but do not seem to speak. We look at them from above, or below, or from an imaginary coordinate, but our surprise at this encounter does not register amongst the figures. They seem to have a much better idea of what is going on, and calmly accept their fates. Their muteness, and their muted almost concrete coloration, give them the feeling of objects. It is as though they are carved out of the scene, then tilted and extruded at various points. They are like the impassive vases and cups of the Italian still life painter Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964), suspended in the zero-gravity of a Russian Constructivist painting.

Chainsawer and Bicyclist

, 2014

Chainsawer and Bicyclist

, 2014

Larsen herself points to the “exploded roof” technique of twelfth-century Japanese painting, where the artist strategically reveals to the viewer that which architecture would otherwise conceal. The technique, in Larsen’s hands, produces pictures that seem constructed by our own viewing, while remaining slightly resistant to our gaze, with each character seemingly concentrating on the task at hand—take, for instance, Sit ups Leg lifts (2012) or Reading in Bed (2015).

Larsen insists that the works are not intended to be alienating but are rather a “non-organic collaboration of parts;” however this quality of “thingness”—the simultaneous sense of solidity and vertigo – can produce the strange emotional dissonance of a drug-induced state, where everyday life suddenly merges, and one begins to feel more and more like a teacup or a table. This is not to say that Larsen’s paintings lack narrative. On the contrary, something is always unfolding within the frame, but this can often be the very source of their abstraction. A figure in action is all the more likely to accentuate the skewed geometry of the composition, and their movement does not necessarily reveal their motivations. In each picture there is a sense of both physical suspension and emotional suspense, as if yet another turn in perspective is right around the corner, ready to change the configuration completely.

– Timothy Ivison

LOUISA GAGLIARDI

Born 1989, Lausanne, Switzerland. Lives and works in Zurich, Switzerland

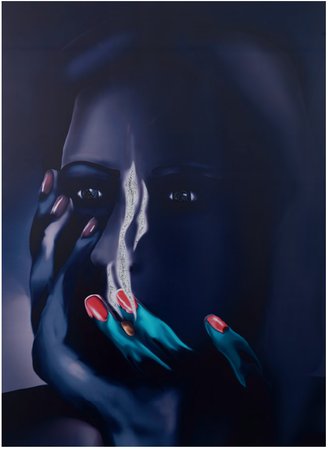

Charlotte

, 2015

Charlotte

, 2015

Specializing in a decidedly sensuous form of contemporary Surrealism , the artist Louisa Gagliardi creates cinematically atmospheric, large-scale artworks—sometimes paintings, sometimes blown-up prints—that seem to show the world through the eyes of a voyeur. Her process, taking subjects from life and then transliterating them through a series of digitally aided moves, gives her work a synthetic, screen-like feel that underscores its noir punch, a style that lends itself to the fashion and design commissions she pursues alongside her art.

Gagliardi attended Amsterdam’s prestigious Gerrit Rietveld Academie and began her career with a focus on commercial work in graphic design and magazine illustration (including POV Paper , a Swiss-based sex and gender publication), as well as collaborations with fashion brands like Kenzo and Alias One. Across these projects, her aesthetic evolved, at once recalling the paintings of the Bauhaus teacher Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1932) and the mechanistic artificiality of Giacomo Balla’s (1871–1958) Futurism , as well as the melting bodies of Salvador Dalí (1904–89) and haunting shadows of Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978). A dark humor is present also, as in a visual dictionary she compiled of “everyday life weapons” that includes remote controls, the sharp edges of coffee tables, staircases, doors and other potentially “violent” objects.

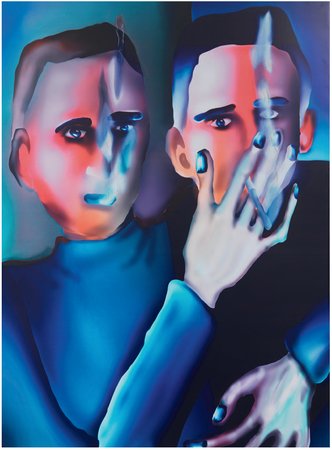

Pierre & Charles

, 2015

Pierre & Charles

, 2015

It was during this time that Gagliardi began painting, developing this practice in parallel with her design work. Her large, close-up portraits of friends and acquaintances are taken from photographs (or sometimes pulled from her social-media network). In works such as Pierre & Charles (2015) or Charlotte (2015), the canvases fit in easily with what we might call “ Post-Internet portraiture”: the face as seen from the glow of the screen as we swipe, ‘like’ and enlarge.

Indeed, in Gagliardi’s paintings the face appears as though it is barely there; like a lava lamp, it is viscous and mutable. Gagliardi exaggerates the moodiness through her use of latex, gel, vinyl, acrylic and nail polish, which she sometimes applies to form characteristic glove-like sheathes around the hands of her subjects, who often hold a cigarette or, as in Evelyn (2015), a smart phone. Her subjects can often appear lonely or detached, drawing our attention to the fact that despite being more connected than ever, isolation and strangeness persists.