Art historians both hate and need “movements.” On the one hand, they like to classify artworks and line up groups of diverse artists into nice linear narratives—what we call the “canon.” But this canon doesn’t always run in the progressive and homogenous way history would like. The Western canon is constantly breaking as peripheral artists begin to surface from history's repressions in the wake of post-colonialism and globalization. Phaidon’sArt in Time is an extensive anthology of global art movements that situates these “outsider” movements within the “grand” history from which they were excluded—spanning from Indian Pharai painting to Bay Area Funk in California during the 1960s (yes, artistic centers did exist outside of New York in the 1960s!) Below, excerpted from Art in Time, we’ve chosen three 19th-century painting movements we’d never heard of, but wish we had.

Yōga Painting

The history of Japanese Western painting, or Yōga, predates the modern era. The earliest artworks in the “Western style” (yōfūga) were created following the arrival of European Jesuits in the sixteenth century, though production in this mode had all but died out by the mid-seventeenth century. With the vogue for Western science (rangaku, literally “Dutch studies”) in the eighteenth century came a renewed, though marginal, artistic practice influenced by Western methods and media that lasted into the early nineteenth century; Western influence can also be seen in nineteenth-century prints by such artists as Katsushika Hokusai (c.1760–1849). But it was with the adoption of the European concept and system of the fine arts in the late nineteenth century that Yōga truly came into its own. As an essential component of an emerging Japanese national art, Yōga was transformed from a scientific, utilitarian tool of dubious aesthetic merit to an ambitious artistic arena for elucidating national character and demonstrating Japanese mastery of international (Western) cultural standards. Such was the work of painter, educator and arts administrator Kuroda Seiki (1866–1924), who in works such as Under the Trees combined identifiably Japanese subject matter with an Impressionism-inflected academicism learned in Paris.

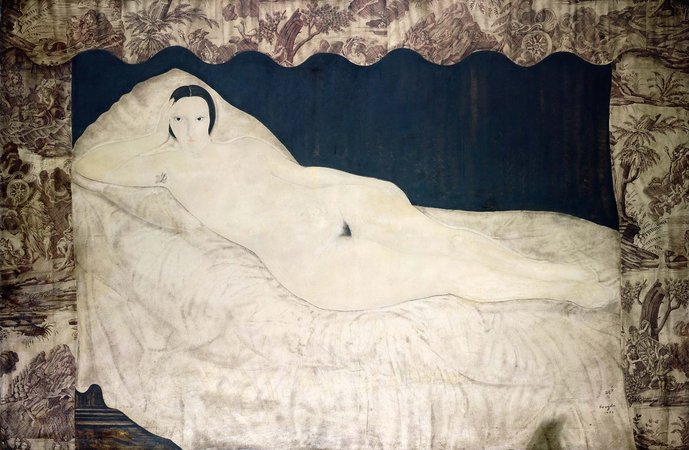

Like its neo-traditional counterpart Nihonga, Yōga has been primarily defined by medium and format, in this case those central to the European tradition—oils on canvas or (less often) watercolors, pastels and pencil on paper. The “foreign” derivation and materials of Yōga frequently posed a hurdle for oil painters, who were criticized, especially abroad, for their departure from Japanese “tradition,” lack of cultural authenticity and lack of originality; such criticism largely stemmed from cultural chauvinism and an orientalist desire for difference that has rarely been fulfilled by Japanese works in oils. The early twentieth-century effort by Yōga artists to adopt materials, formats, and subjects more closely associated with Nihonga and with Japanese premodern painting traditions was one answer to this dilemma, and considerable stylistic overlap existed between Yōga and Nihonga in the 1920s and 1930s. Paintings in this vein by Fujita Tsuguharu (1886–1968), such as Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy, met with great acclaim in Europe. They combine oils with mineral pigments and other materials proper to Nihonga to achieve a new vision of the nude, a traditionally European genre. The simultaneous exploration by Yōga artists of the two supposedly antithetical painting modes of Yōga and Nihonga was also related to the influence of Japanese painting and printmaking on European painting styles, and the fact that the line between Eastern and Western artistic traditions had already been blurred for generations.

Yōga’s place in the cultural consciousness was cemented with the onset of the Pacific War (1941–45), when in large-scale “war record paintings” (sensō kirokuga) oil painters resuscitated Western-style history painting to aggrandize the Japanese war effort. In the decades following the immediate post-war period, as artistic media diversified both overseas and in Japan, Yōga became increasingly inward-looking and conservative, an easel painting of the Japanese establishment that remained squarely in the tradition of prewar painting trends.

Nabis

The fin de siècle witnessed a growing fatigue with the emphasis on perceptual phenomena that concerned the Impressionists, and that disenchantment saw an increase in the subjective interpretation of visual information, of sensations and ideas, and of the formal characteristics of the picture.

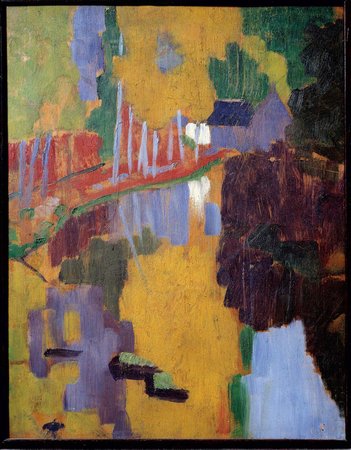

Maurice Denis (1870–1943), along with several other students who studied at the Académie Julian, including Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940), Paul Ranson (1864–1909), and Paul Sérusier (1864–1927), banded together in late 1888 to form an artistic alliance that was subsequently dubbed the Nabis, from the Hebrew word meaning “prophet.” The Nabis viewed themselves as a brotherhood and as seers, moving beyond the world of mere appearances to reveal something more profound. Sérusier was heavily influenced by the time he had spent with Paul Gauguin in Pont-Aven during the summer of 1888. Exposed to Gauguin’s Synthetist ideas, he had eschewed objective rendering in favor of bold simplification of form, an emphasis on the decorative patterning of flat areas of color and the subjective deformation of nature. The result of his experiments with Gauguin’s Synthetist teaching can be seen in The Aven River at the Bois d’Amour, painted on a cigar box top. Subsequently dubbed The Talisman by his fellow Nabis, the painting retains enough reference to reality as to be identifiable, but only just. According to Denis, Gauguin instructed Sérusier to deviate from a mimetic use of color: “How do you see these trees? They are yellow. Well, then, put down yellow. And that shadow is rather blue. So render it with pure ultramarine. Those red leaves. Use vermilion.” The row of trees lining the path that cuts diagonally in from the left helps to orientate the viewer, but spatial recession is denied by the radical simplification of details, broad areas of bold color, and equalizing of the solid objects and their reflection in the water in the lower half of the picture.

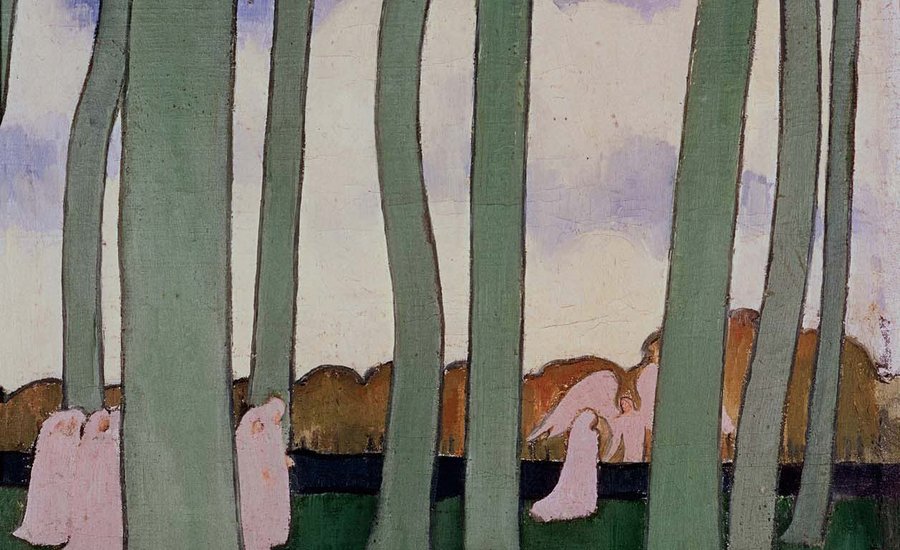

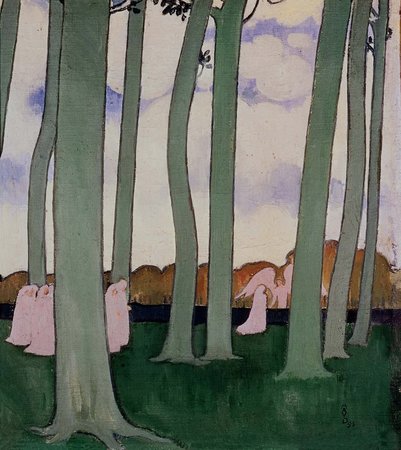

Denis’ own works also reflect the emphasis on the two-dimensional surface and a renewed appreciation for decorative patterning. His Landscape with Green Trees demonstrates extreme simplification, bold, non-mimetic color and absence of modeling that emphasizes the pictorial surface. A procession of white-clad figures glides through the pale trees, towards a wall where one of their group encounters an angel. The lack of narrative and objective detail contribute to the painting’s evocative quality.

While there are overlapping concerns between the Nabis and Symbolism more broadly, many of the artists associated with the former were also interested in expanding decorative painting to the architectural interior, an interest shared with Art Nouveau artists. In 1894, Vuillard was commissioned to produce nine panels for the Paris residence of Alexandre Natanson, a founder of the avant-garde journal La Revue Blanche, to which Vuillard provided lithographs. Vuillard’s Girls Playing is insistently decorative, a quality emphasized by the vertical panel, minimal detail, unmodulated patches of matte color, and relatively high horizon line. While the nine panels function admirably as independent works, each picture’s corresponding horizon line and the repetition of foliage links them, a testament to Vuillard’s exquisite design sense.

Juste Milieu

Reference to the Juste Milieu art movement is often made to designate some of the art produced during the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe in France (1830–48), especially works that seem to attempt a harmonious synthesis of opposites. Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans, ascended to the throne after the abdication of Charles X, following the uprisings immortalized by Eugène Delacroix in his monumental July 28: Liberty Leading the People, shown in the Salon of 1831. Louis-Philippe set a new political tone; because he did not rule by divine birthright, his reign was conciliatory, attempting to appeal to all parties, and was referred to as the “ideal compromise,” or juste milieu.

As a stylistic designation, Juste Milieu is not an unproblematic term, but in general it signals an art that eschews extremes in favor of a historically synthetic approach. Charles Baudelaire quipped that the artists of the July Monarchy might be grouped into “linearists, colorists, and doubters,” though art critic and painter Henri Delaborde, referring specifically to Paul Delaroche (1797–1856), might be more illuminating: “Between the apostles of regeneration to excess and the stubborn defenders of the past, a third party was formed, that of the moderates.” Delaroche’s Execution of Lady Jane Grey depicts the beheading of the young Protestant Jane Grey in the Tower of London on 12 February 1554. His choice of subject and moment, as well as the composition, seem intended to maximize the sense of pathos. The blindfolded martyr is centrally placed just before the executioner’s block; the executioner himself stands with his hand just grazing the handle of his axe. Two ladies in waiting are depicted in the throes of grief, presenting a stark contrast to the nonchalance of the executioner. Delaroche’s painting demonstrates a scrupulous attention to historical accuracy in terms of costume and architectural setting, and yet has about it a quality of stylistic neutrality that places it in a different camp than either the emotionally charged romanticism or the high-minded didacticism of the Davidian school of Neo-Classicists, though it draws upon both. The tripartite architectural division in the background of the shallow space may be an oblique reference to the triple arches of David’s Oath of the Horatii. But while David’s paintings make grand statements about civic obligation and righteousness, Delaroche’s work reads more like a theatrical staging or a historical genre painting than a history painting in the Grand Manner.

This more anecdotal nature can also be found in the work of Horace Vernet (1789–1863). The Duc d’Orléans on his Way to the Hôtel-de-Ville, 31 July 1830, shown in the Salon of 1833, provides an instructive contrast not only with Delacroix’s painting of events related to the July Revolution, but also with Baron Gros’ great propagandistic glorifications of Napoleon, such as the 1808 Battle of Eylau, to which Vernet makes reference in the general composition and the specific pose of the leader on horseback. But while all aspects of Gros’ painting exalt Napoleon, Vernet delights in a proliferation of anecdotal detail that relegates the Duc to the middle ground. Vernet’s painting, commissioned by Louis-Philippe, is not devoid of a political message, but its ideology is muted in favor of harmonious compromise.